A little island on Pier 55: urban austerity and the eclipse of publicly made public space?

– Anthony Maniscalco

They say history is written by the winners. When public space is constructed and regulated at the behest of park conservancies, public-private partnerships and other neoliberal devices that empower largely anonymous board members over citizens seeking to participate in community planning processes, it may prove challenging to disaggregate history from victory.

Right now, construction continues on “Little Island,” a two-and-a-half-acre futuristic park development on Manhattan’s Westside. The so-called island will “float” above Pier 55 along the New York side of the Hudson River, seated atop dozens of piles driven deep into the bedrock below the murky, slowly remediating waters that run between the Big Apple and New Jersey.

1. Little Island render. Source: © Pier55, Inc. and Heatherwick Studio, Render by Luxigon.

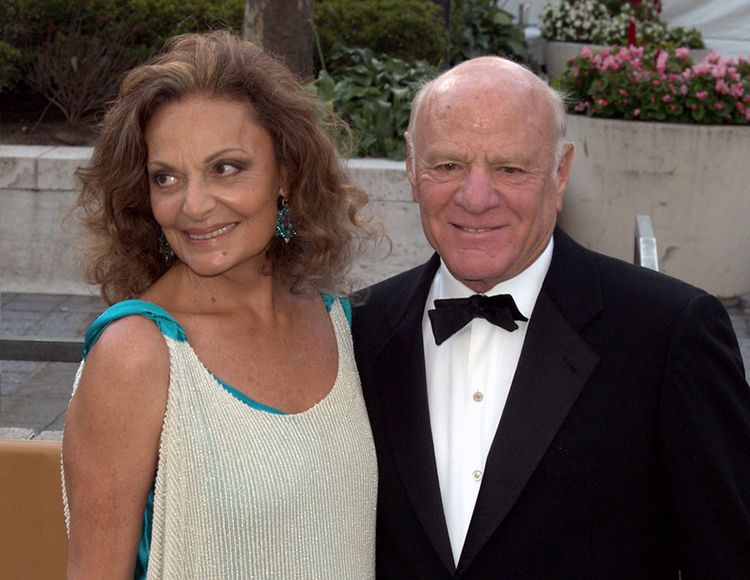

As public spaces go, there is little doubt that the development project, now estimated to cost $250 million, will assert itself as one of the most innovative park designs in history, nationally and internationally. Designed by Britain’s Thomas Heatherwick, the tour-de-force development is ground-breaking. Indeed, the distinctiveness of the design initially led many notable architectural critics to characterize the entire project as the “pipedream” of a bored billionaire, Barry Diller, along with his celebrity accomplice, Diane Von Furstenberg and the well-heeled President and CEO of the Hudson River Park Trust, Madelyn Wils.

For more than two years, a well-documented struggle ensued over the project, producing an intermittent improvement saga in New York City’s Meatpacking District, a rapidly gentrifying area of Manhattan, shaped by shifting demographics and fiscal priorities. Pier 55 earned tacit approval from the local community board while a host of elected officials vociferously joined the cause as economic development boosters. They included Mayor Bill de Blasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo, who rarely agree on anything concerning New York City’s landscape. The project passed subsequent muster inside the courts of law and, perhaps more significantly, at the Army Corps of Engineers, which eventually gave its blessing after a much-abbreviated environmental review process.

Though it is not exactly the stuff of legend, the backstory of the project, and the controversy surrounding it, both deserve comment. Much of what we know about the development is found in newspapers, owing to deep layers of secrecy that cloud the larger story behind this unique scheme for a public park built by private agents.

In 2012, representatives of the Hudson River Park Trust approached Diller and Von Furstenberg, hoping to attract financial support to rebuild the defunct Pier 54, which still sits on the Hudson River near the West Village. The billionaires’ enthusiasm for that terribly deteriorated waterfront parcel was modest, to say the least. However, these would-be philanthropists hatched an alternative idea for a park o’er the water; the park would be centered on Pier 55 and it would replace Pier 54 altogether. They then charmed representatives of the Hudson River Park Trust (the private conservancy charged with developing the waterfront along the Westside of Manhattan) to construct a model. Thus a prototype was built to scale, practically, and then artfully displayed at a well-appointed estate on Long Island.

2. Barry Diller and Diane Von Furstenberg. Source: David Shankbone, NYC 2009.

Here was the Little Island, which early observers derisively dubbed “Diller Island,” a dishonor intended for the billionaire financier and a conservancy-led cabal that dreamed up the park in the first place. The project was to be privately financed for the most part, with relatively modest infrastructure investments by the City of New York, initially valued at $17 million (though many challenge the accuracy of that figure). Diller and Von Furstenberg themselves would raise the remaining proceeds—once numbered at $117 million—calling on their friends in Hollywood and the music industry for the rest, bundled under the auspices of a non-profit organization created for this purpose. There would open spaces for recreation, and there would be spaces for public programming, such as a concert stage for paid performances.

No surprise, a brouhaha erupted when elected officials, neighborhood organizers and municipal advocates—most notably the City Club of New York (a civic organization that did battle with Robert Moses in the 20th century)—raised concerns about the secrecy surrounding the fundraising scheme, as well as the integrity of the environmental review process. They also attempted to call attention to the dubiousness of building a new project while half of the Hudson River piers languished in ill repair. They were no more enthusiastic about the paucity of community input into the park’s design and programming features. Finally, they expressed intense skepticism about how publicly accessible a privately financed park would ultimately be to people unable to foot the bill for classical music concerts and other ticketed events. Such occasions are pegged to represent no less than 49% of the “public programming” on the park parcel above the water.

In other words—and quite aside from the in-fill island’s potentially devastating impact on improving ecosystems in the Hudson River, specifically, a returning estuarine that may be obliterated when the pile drivers hit the bedrock that girds the project—a serious question had emerged over how public this public park would be after its construction. Notwithstanding philanthropic motives for building a public space, when one is privately developed, an impressive array of exclusions becomes feasible, if they do not become the order of the day, that is. Similarly, the rapid rise of government austerity measures and the attendant call to private developers to build projects like Little Island must raise serious questions about the transformation of urban public space in the 21st century. The Occupy movement in New York and other cities has surely drawn attention to the POPS (privately-owned public spaces) phenomenon, a trend examined by Kayden (2006) and, more recently, Shiffman et al. (2012) and others concerned with lax enforcement of the administrative rules governing numerous covenants between cities and the landlords who construct and control access to places such as Zuccotti Park (and, yes, Trump Plaza).

3. Little Island construction site banner. Source: littleisland.org

Indeed, the Pier 55 development may represent a more troubling advancement in this regard. Inasmuch as Little Island will be privately built and then operated by a private trust, users may be subject to a legal doctrine historically relied upon by property owners to exclude publics from shopping malls and other gathering places: the state action doctrine. In the courts of law, state action has proven itself a miserably convoluted doctrine that ultimately protects the right of private property owners to prohibit unwelcome public activities when they see fit to do so. In the area of free assembly and expression, specifically, the state action doctrine has been interpreted to mean that government entities alone are legally prohibited from excluding publics without cause under the U.S. Constitution (“Congress shall make no law…”). On the other hand, the doctrine has treated property owners very differently. It defines them as private citizens who are fully within their right to exclude activist segments of the public from sharing their ideas inside shopping malls, most notably—notwithstanding the invitations they issue daily to those same publics for purposes of buying goods and accessing a growing array of public services housed within older, enclosed malls and their New Urbanist outdoor incarnations.

4. Little Island under construction. Source: littleisland.org

Thus, the Little Island is being built, and it will go online in 2021. And it may indeed deliver the array of public benefits ballyhooed by its supporters. Still, I think some intense scrutiny will be merited with respect to the privately funded park’s public programming. When it comes to accessibility and enjoyment, will park permissions be unfettered? Will Little Island be for everybody? Will skateboarders be able to use the park for thrills? Will poorer families who still live in the area be able to barbecue there, particularly, when wealthier subscribers roll in via limousines to watch the opera? Will homeless people be permitted anywhere near the three performance stages for that matter?

We may not know until the “Rules of Usage” sign goes up. If the history of this development proves to be any guide, decisions about public access and permissible activities will likewise become private matters. This is the point I wish to emphasize. Even if Little Island detractors are wrong and the park proves accessible to publics across the City—rather than the exclusive and perhaps exclusionary haunt of wealthy people able to afford its programming—I think this development ought to spur critical examination of a growing propensity to rely on private financing to deliver urban public goods. In a climate of austerity, where government funds are frequently withheld from parks and other vital amenities to our public sphere, we have turned to conservancies and other privately-structured artifices to build and sustain our shared spaces.

It wasn’t always this way. And while it is unwise to idealize the past or cling to concepts outdated by the social and political conditions that gave birth to the Hudson River Park Trust and its cousins, we ought to consider the “market as prison” dynamic described by Charles Lindblom (2001). Lindblom concluded that we have systematically foreclosed the possibility of challenging ourselves to think outside the box of capitalistic solutions to public problems.

Whether or not Diller, Von Furstenberg and company will tightfistedly “control the key” to Little Island, as one online critic recently decried, it may still be fair to assert that we have too often locked ourselves into placemaking approaches that eschew significant government investment, and therefore meaningful public input. Notwithstanding the austerity imposed by the Great Depression and America’s entry into World War II, public investment has generated impressive iterations of space in the U.S., and that version of placemaking has promoted a richer public sphere at many times in American history. The Public Works projects of the New Deal were surely as impressive as Pier 55. They also put millions to work and helped create a middle class in this country. Great Society programs helped extend that prosperity to untold numbers, while providing roadmaps for social inclusion the likes of which were previously unwitnessed. Indeed, the need for public infrastructure and improvements on failing physical plants helped animate President Trump’s successful campaign in 2016. Yet, we see too little pushback against the White House promise to subsidize new construction and remediation via massive tax cuts to private builders, who will purportedly give us our roads, bridges, and airports.

Many of us may experience an uneasiness about who Little Island is built to serve, not to mention who has rights to inhabit the park apart from its prescribed users and uses. The project’s private development and a planning process that included too little public input fuels that unease. So, too, does the seeming default judgment that public bodies can no longer put public space online.

References

— Kayden, J. (2006). Privately Owned Public Spaces. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

— Lindblom, C. (2001). The Market System. New Haven: Yale University Press.

— Shiffman, R., Bell, R., Brown, L. J., and Elizabeth, L. (2012). Beyond Zuccotti

Park: Freedom of Assembly and the Occupation of Public Space. Oakland, CA.: New

Village Press.

Dr. Anthony Maniscalco teaches at the City University of New York (CUNY), where he also serves as a Senior University Director. He earned his doctoral degree in Political Science at the Graduate Center and University Center. He is the author of Public Spaces, Marketplaces, and the Constitution (SUNY Press, 2016).

Volume 3, No. 1 February 2020