Biophilic cell in the city

– Divya Mishra

Water and civilization

The availability of water has shaped civilizations for millennia. Water crosses international and interstate boundaries, while man tries to control it for economic and social gains. Other than benefiting directly by fulfilling basic needs and building the city’s economies, people are associated with water through a system of beliefs, culture, and traditions, to form a dependency that creates a sense of ownership, defence, and security. This dependency leads to stewardship, developing customs to represent gratitude and respect towards the natural assets, through a system of faith and rituals. These rituals change according to Ritus (seasons) in India.

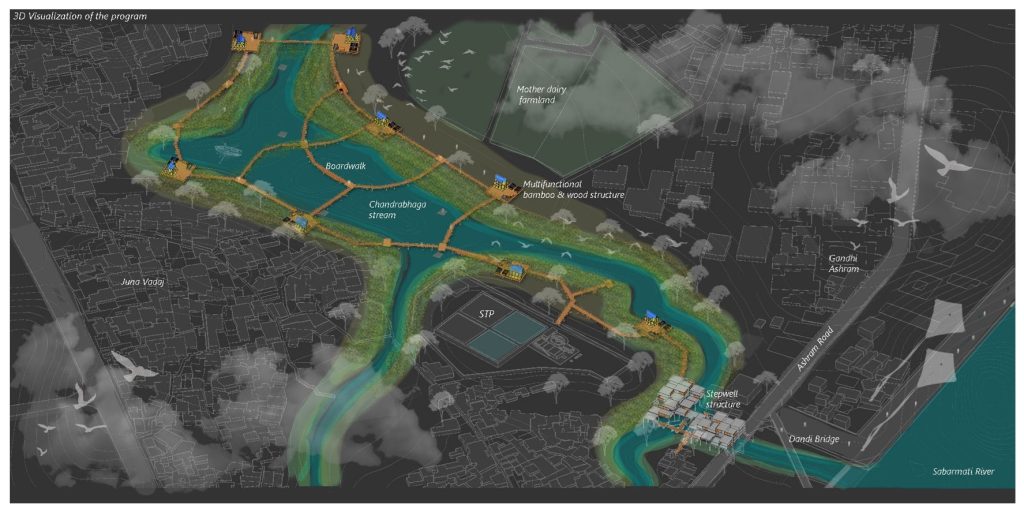

Image 1. Located in the city centre of Ahmedabad, the map shows how the Chandrabhaga stream, a small tributary of the Sabarmati river, becomes a victim of urban sprawl. Source: Author.

Chandrabhaga stream

Chandrabhaga is a small tributary of the Sabarmati river flowing through Ahmedabad and with its origin near the Adalaj stepwell [Image 1. Fig.1a]. It is said that a huge depression acted as a reservoir in the stepwell backyard and held a large quantity of water, which percolated & entered the stepwell after filtration as sweet water. Along with the locals, communities1 of farmers and Khumbhar (potters) were dependent on Chandrabhaga water for agriculture, cattle rearing & pottery.

Highlands and lowlands

As the city expanded, urbanization led to changes in land use, filling of lowlands, shifts in occupation from the primary to the secondary and tertiary sectors, construction of transport infrastructure and institutions. This further resulted in educated and wealthy people occupying the well-developed highlands. Urban water and displaced people accumulated towards the lowlands and stood victimized due to waste and sewage dumping and seasonal flooding. Centralized water supply and drainage infrastructure in urban areas lead to sociocultural disconnection from natural resources. [Image 1. Fig.1b]

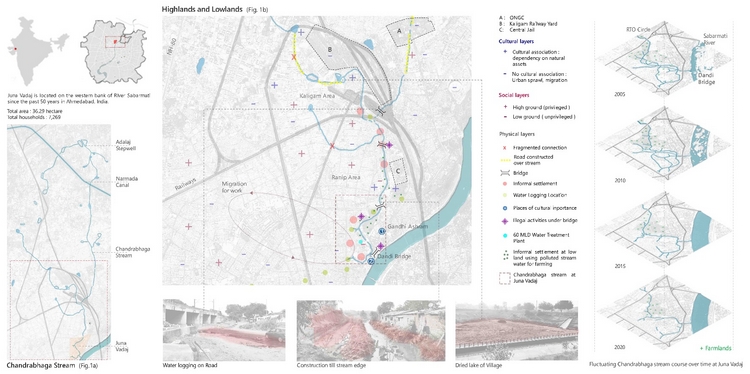

Image 2. People have migrated as there is a loss of dependency and connection with the water as a source of livelihood, resulting in the formation of large informal settlements near the low-lying area of the Chandrabhaga stream. Source: Author.

Current scenario

Construction of the Narmada canal diverted Chandrabhaga from its original water source. As a result, most of the village lakes dried up, and eventually, people became more dependent on centralized water connections. Seasonal flooding began in urban pockets due to this disconnection and due to increased paved areas. To avoid flooding, people started construction at a higher ground level, matching the level of bridges by filling the land. This topographical difference created a separation in people’s activities and living conditions in the new highlands and the stream edges that became lowlands. Today, in Ahmedabad, the city’s waters are struggling for survival. They have become the victim of urbanization: pitched, fixed, constrained & channelized.

Chandrabhaga at Juna Vadaj

Lowlands are surrounded by elevated city roads whose water drains into the Chandrabhaga, creating a polluted area that adversely affects the residents. In the absence of adequate waste and drainage infrastructure in lowlands, nearby dwellers dump the garbage directly into the stream. This creates multiple issues such as foul smells, ill-health, and exacerbated conditions during floods when backflow occurs from the stream. [Image 2.] Today, the Chandrabhaga’s water is rendered useless to former farmers, fishermen, and potters. To find the middle ground between the chaos of highland and lowland, a few questions arise:

How can one manage the waste in the water system and generate an economy out of it?

How can one bring a sense of responsibility, ownership, and stewardship to the urban commons of water?

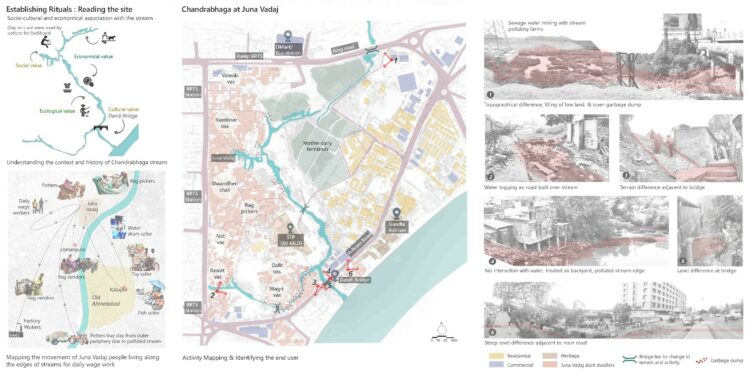

Image 3. The idea is to revive the lost identity of the Chandrabhaga stream by treating its polluted water, which will act as a catalyst and lead to holistic development by creating a middle ground between the high land and low land of the city. Source: Author.

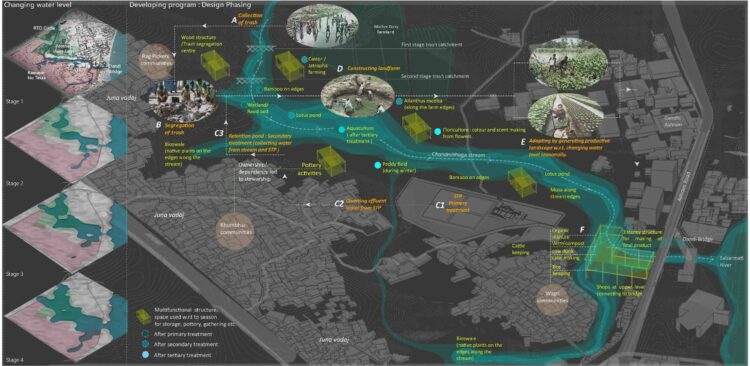

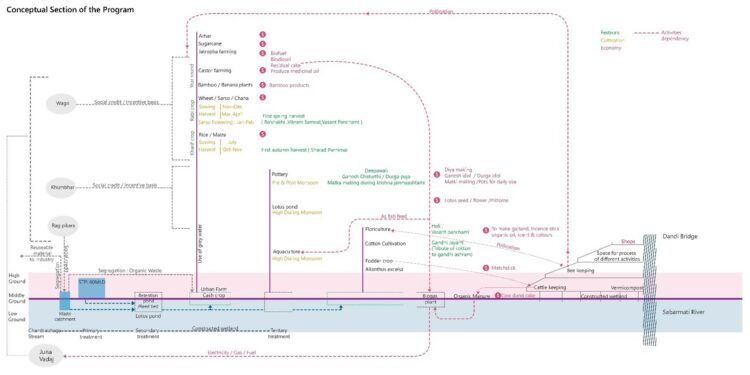

The gradient from high to low is not just a difference in topography but also in social and environmental equity. Instead of breaking the chain of dependency between highlands and lowlands, the idea is to intervene in the middle ground to cater to these concerns, where water & Vadaj communities can co-exist. This further aims to generate livelihood through resilient, sustainable, and productive landscapes, by adopting a strategy that changes with the flux in water levels during different seasons. [Image 3.]

RE-IMAGINING THE CHANDRABHAGA STREAM

Design strategy

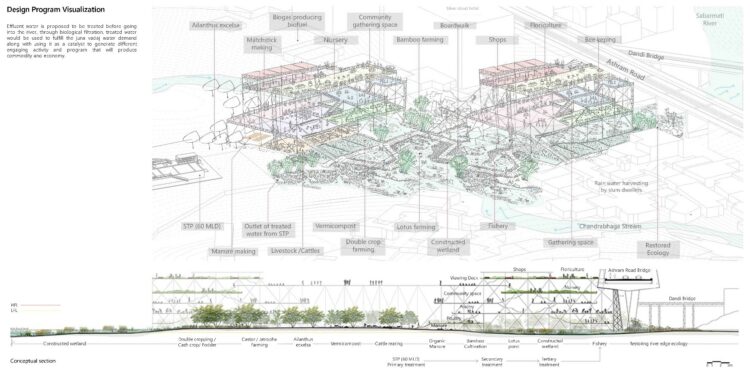

The key idea is to develop methodologies that will allow people to help manage their environment by segregating waste. Currently, polluted water from the stream and the installed sewage treatment plant (60 million litres per day) is emptying directly into Sabarmati. The strategy aims to utilize both sources of greywater before the confluence with Sabarmati to generate new economic and social opportunities that will benefit the locality. [Image 4.]

Image 4. Using the two water sources, one from the sewage treatment plant (primary treatment) and the other from a polluted stream going into Sabarmati. Productive landscape activities using greywater will take place simultaneously along with water treatment. Source: Author.

Image 5. Illustration depicting the process and different stages of water purification & the productive landscape. Source: Author.

Design Phasing [Image 5.]

Collecting: Locals will be involved in trash collection throughout the stream, through incentives and social credits. As a result, they gain responsibility for the land and water along the stream for different purposes.

Segregating: The process starts with collecting trash, segregating it according to different uses. Organic waste can be used in agriculture or to produce biogas whereas reusable items can be sold at flea markets or be taken to the industries through various stakeholders. Existing ragpicker communities of Juna Vadaj can be involved through social capital credit.

Constructing: Once the trash is removed, existing land is modified with regards to the flood level through the cut and fill technique. Locals will then start to transform the land for productive purposes and earn social capital credits.

Adapting: This process shapes the landform in a terraced manner, such that the land can be cultivated according to fluctuating water levels. These terraces can have multiple functions and programs, responsive to the settlements along the stream. The role of the adjacent infrastructure will also change following the season and programs.

Interdependent activities: Activities positioned at the edge of the stream are associated with different levels of water purification and are interdependent.

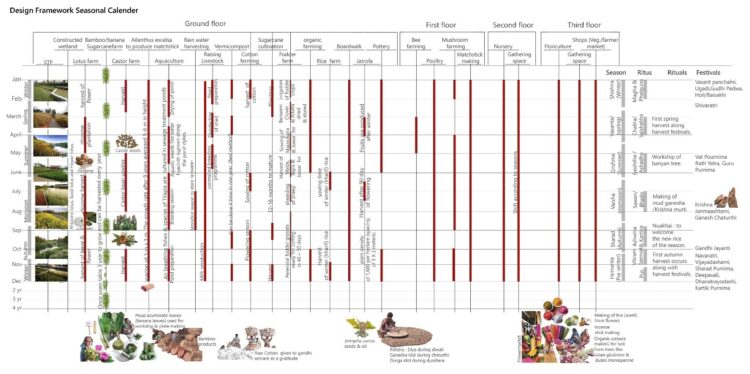

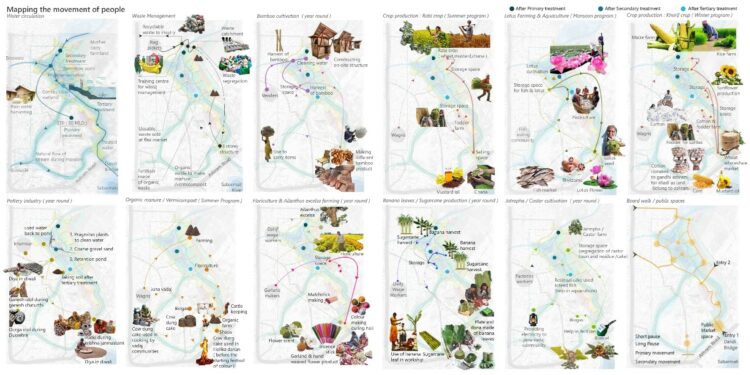

Image 6. For any program to thrive, there is a need for a belief system that works on faith and takes place only when there is a sense of dependency, belonging, and ownership. The figure demonstrates the seasonal working of each program. Source: Author.

Linking people with the program

India’s culture resonates with its rituals, traditions, and religion. People bow to the earth which provides them with food, air, and water. According to the Hindu calendar, Vikram Samvat (new year) starts with the first winter harvest which marks the festivals of Makar Sankranti or Vasant Panchami in different parts of India. These rituals enthuse the people and bind them with designed programs2. [Image 6.]

The strategy enables the transformation of the city’s unused greywater into a useful resource that will benefit communities by providing social and economic equity through a productive landscape. The project envisions a sustainable and resilient approach to city planning while reviving the lost identity of natural stream water in the context of Ahmedabad.

Image 7. The conceptual section shows low ground in blue and high ground in red. The design program indicates a violet line, which forms the middle ground. The process of the whole program is from left to right. Source: Author.

Image 8. The mapping demonstrates the movement of people and the function of activities according to different seasons in the program development through a productive landscape. Source: Author.

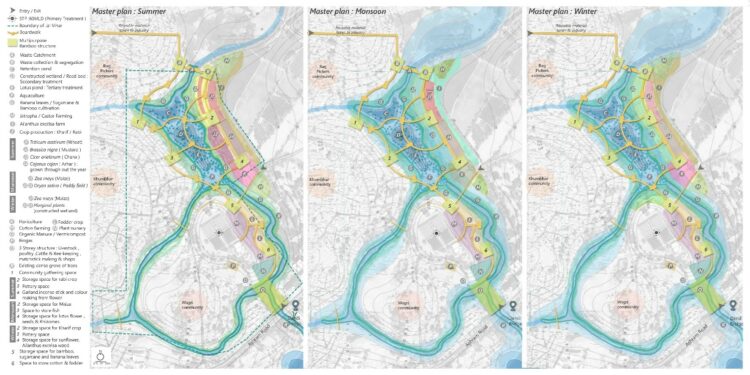

Image 9. The master plan of Chandrabhaga at Juna Vadaj area during Summer, Monsoon, and Winter demonstrating seasonal variation in activities. Source: Author.

Image 10. Conceptual Section demonstrating the constructed landform created through the process of cut & fill resulted in terraced farming. The program transforms according to different seasons and will enhance groundwater recharge. Source: Author.

Image 11. Conceptual visualization depicts the Monsoon and Summer season at the confluence point of Chandrabhaga stream & the Sabarmati river, where program ideation is bridging the gap between low land and high land. Source: Author.

Image 12. Illustration of one pause point within the site showing program activities along the Chandrabhaga stream. Source: Author.

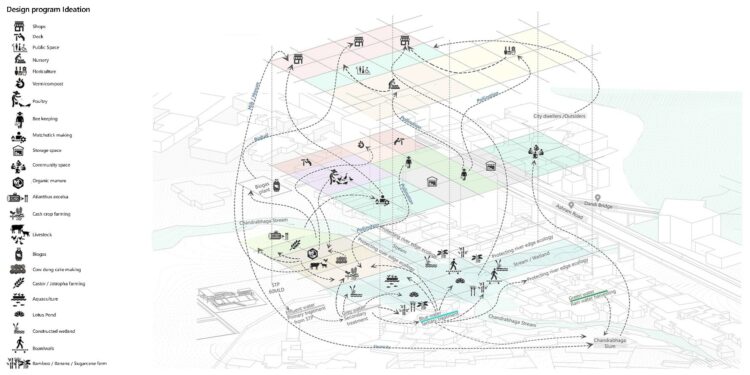

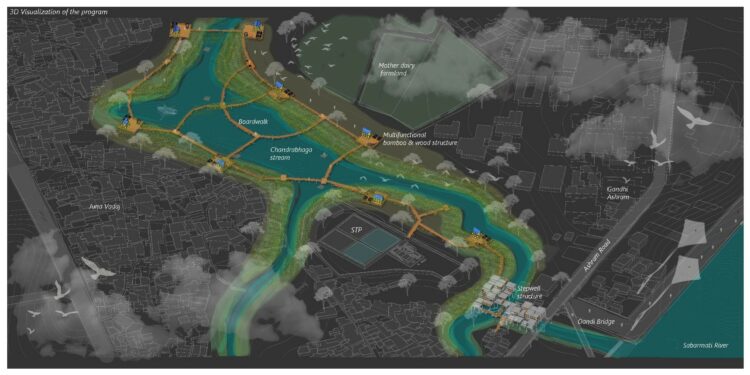

Image 13. 3D visualization of the project idea. Source: Author.

Notes

1. The communities living in Juna Vadaj are Khumbhars (potters), Dalit, Wagri peoples, and Ragpickers. It says that most of the land was owned by the Gandhi Ashram and was given to Wagri communities to practice agriculture and run their livelihood.

2. Some rituals could be self-built through a system of beliefs and faith. Forex. Wagri community received the land from Gandhi Ashram for agriculture that could be programmed to cultivate cotton in the design. Along with commodities in the market, the first harvest could be given to the ashram on 2nd Oct (Gandhi Jayanti) as gratitude, which will promote khadi.

References

— GSAPP, W., 2021. Water Urbanism Varanasi – Columbia GSAPP. [online] Columbia GSAPP. Available at:

— GSAPP, W., 2021. Water Urbanism Can Tho – Columbia GSAPP. [online] Columbia GSAPP. Available at:

+

The work presented in this article has been conceived as a part of the “Re-imagining Water” studio thesis project 2020, guided by Sandip Patil under the Masters in Landscape Architecture program at CEPT University, Ahmedabad.

Divya Mishra is a landscape architect who completed her master’s in Landscape Architecture at the CEPT University, Ahmedabad. Before beginning her post-graduate, she worked in a Varanasi based firm and has been part of various cultural, natural heritage conservation, regeneration, and water urbanism projects. Major ones are the Namami Gange Project (Integrated development of ghats and crematoria along the stretch of River Ganga in Varanasi), the renovation and retrofitting of Manikarnika cremation ghat, and the Varanasi and Narmada Riverfront Development under the Smart City Project, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Both professionally and academically she has been working towards the concept of making cities climate responsive, resilient, sustainable, socially inclusive, culturally vibrant, and economically competitive by reactivating their unique cultural and natural assets.

Volume 4, no. 1 Spring 2021