A Community Project: the students have their say, what can we learn?

– Karine Dupre and Ruwan Fernando

The Gold Coast of Australia is noted for its real estate development around artificial canals connected to the Pacific Ocean. The coastline has been altered from the growth of both the tourism industry and the population, from 8,400 inhabitants in 1947 to over 555,000 inhabitants today (ABS 2015). Several districts have emerged from this process and Surfers Paradise is one of them, standing as an example of the densified waterfront, concentrated services, tourist attractions and housing.

In this context, one would expect that all the coastal land that bound the main hubs of the Gold Coast (Surfers Paradise and Southport being key examples) would have also undergone rapid urbanization during this period. Yet, an exception to this comes as the Spit, a strip of land of about 180 hectares between the districts of Southport and Surfers Paradise (Fig. 1).

1. The Spit © Dianne Dredge

Born from a series of storms that have reconfigured the sand dunes at the mouth of the Nerang river (GCCM, 2006), this land protects the Southport district from the extreme weather from the Pacific Ocean and creates a bay that appeals to water activities and navigation.

The Spit has quickly become an attraction to the Gold Coast residents with strong social and cultural significance (Bosman & Strickland 2015). Embracing this phenomenon, the city committed to dredging the marine environment to counteract the Spit’s erosion and maintain the Broadwater (the shallow water estuary which includes the Spit and Wavebreak Island). Yet, for the last fifty years the site has also seen many proposals for development and just as many protests and opponents. Some proposals, related to tourism and commercial development, have been approved despite the protective regulations in place, for example the theme park ‘Sea World’, a shopping precinct, a commercial fishing wharf, an exclusive resort complex and an international hotel and apartment complex during the 1990s. Since then, development has been frozen, though new proposals are regularly introduced, feeding the development controversy of the site and the counter-reactions of locals. Conflicts over development versus place-value seem to dominate the Spit discourse in recent times (Dupre & Bosman, 2017).

The Student Brief

It is in this historical context that first year Master of Architecture students at Griffith University (Australia) were asked to participate in the debate. Since 2005, there have been proposals to build a cruise terminal and related services on the secured part of the Spit. After many resurgences as well as protests, these have been abandoned with the proposal of a casino (in 2016) being the latest controversy.

The 30 students were asked to design a casino for the city of Gold Coast with the Spit as their site. The majority of the students reside on the Gold Coast (83%). Furthermore, 40% of them consider themselves to be ‘locals’. The students gained direct information from advocates both pro and against development. They had 14 weeks (the length of a semester) to propose a master plan for the site and a more detailed version of the casino. A design competition was organised to evaluate the projects.

Methodologically, we implemented two types of assessments. The first one consisted of three analytical criteria to assess the students design ethos:

- Does their nationality impact the perception of the site’s cultural value?

- Does the site’s cultural value diminish in light of the the full account of key planning challenges?

- How do their casino designs compare with traditional and current trends in casino design?

The second assessment was evaluated by external practicing architects, who constituted the jury of the competition. The jury included the city architect, two architects not residing on the Gold Coast, a local architect, the architect from the official proposal and one architect from the local association fighting the project. Their evaluation criteria related to the quality of the concept and design process; the architectural quality of the design proposal; and the the quality of the presentation (graphic and oral). The following report summarises the students views, values and the lessons we can learn from them.

Observations of the Student Proposals

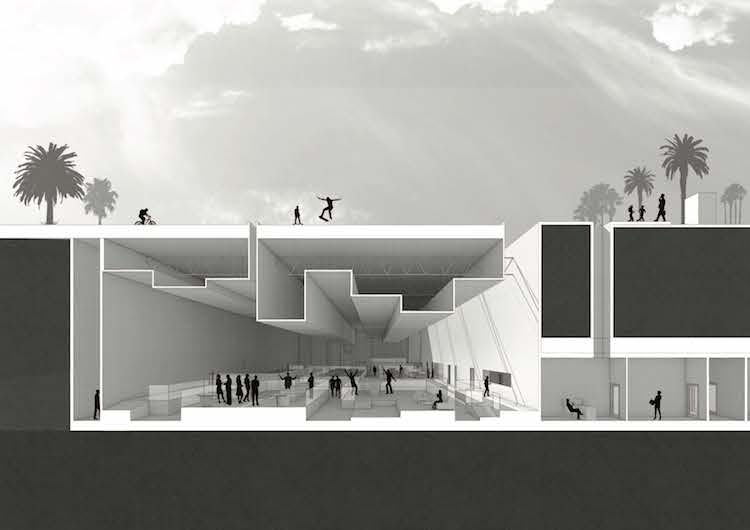

Firstly, being international or domestic student did not have a significant impact on the students’ perception of the site’s cultural value. All the students valued its natural (and protected) environment and saw it as a strong element in their urban proposal. More than 80% had their casino completely surrounded by a huge park (Fig. 2), sometimes completely hiding the casino underground (Fig. 3). As such, it confirms the idea that a site has its own genius locus, visible and perceived by all, as described by Norberg-Schulz (1980).

2. Master plan with predominant park, proposed by C. Villegas

3. Section through the below ground casino proposed by S. Smith

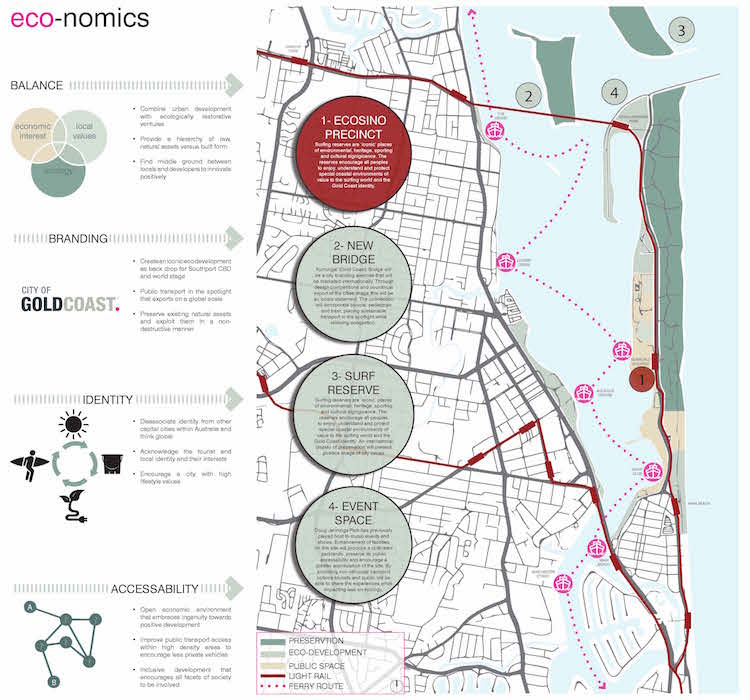

The second observation regards the planning of the precinct. The Spit in its current state, forms a cul-de-sac with regular heavy traffic congestion. All the students addressed this issue in their proposals, not only showing their awareness of linking each project with the city, but also, for some of them, transforming this into a key feature (Fig. 4). As such, it demonstrated that, despite their full acceptance of the site’s cultural value, they avoided both traditional design outcomes as well as non-situated (or sculptural) designs. Not only does it confirm that students at this stage have integrated the variety of scales in their address, but also show problem-solving techniques to help them to prioritise and hierarchise strategies.

4. Master plan, proposed by D. Lovell

The last observation is that the the majority of students did not want their casino to ‘look like a casino’. The projects took many forms including of a resort village, a hotel, a commercial center, art gallery or hybrid types suitable for a public institutions (Fig. 5). There was a strong resistance to adopt the more traditional idea and aesthetic of a casino, with the view that many of the most well-known examples showed kitch and were insufficiently imbued with architectural ideas. Conversations with students showed that they were more concerned with the buildings connection with public space and the long-term appropriation of the building into the site. Adaptive reuse is common in the Gold Coast and the students were anticipating a change of use within a short period. Their interest in having the building very private with high security requirements as part of a general public-perceived complex also demonstrates their attachment to the Spit, as defended and valued by the locals. This is a value unanimously praised by the competition jury for the three first prizes.

5. Projects by J. Hon (top) and B. Campbell (bottom)

Comments from the Jury

Although the two second entries (see Fig. 6) also clearly created a dialogue with the city of Gold Coast’s reputation (‘glittering’, ‘iconic’… or ‘ugly’ (Boyd, 1960)), the first prize design took a completely different approach.

6. Second exaequo entries Master plan, proposed by V. Nunan (top) and M. Trifunjagic (bottom)

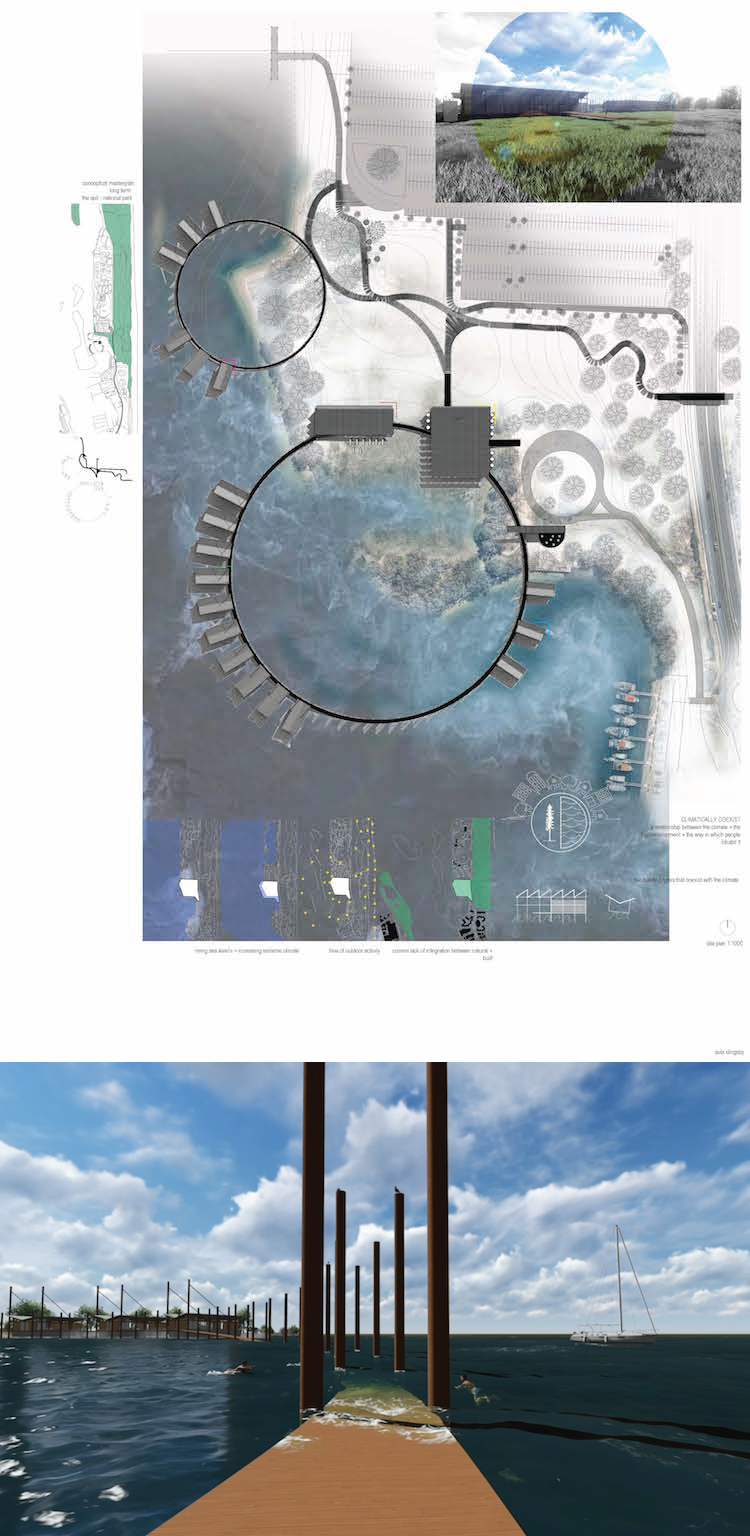

As the history of the development of the Spit is part of a cycle of conflicts quite recurrent in the city, the student chose to develop an offshore proposal to create zero footprint on land and raise awareness of climate change and its impact on sea level. By proposing a submersible jetty around which small cabins, which can accommodate gambling areas or bedding, are floating, the student aimed at introducing the notion of risk and awareness of the fragility of our constructions. The choice of timber also aligned with this narrative as a mean to express a more humble attitude (than heavy concrete docks for example), as well as a return to the basics of sustainable development. Most importantly, by thinking out of the box and already for tomorrow, the jury praised the new type of destination that this project would provide if it was ever built: a mixture of activism, poetry and design skills.

7. 1st prize masterplan (top) and perspective of the project underwater (bottom), laureate Sobi Slingsby

Summary

Unanimously praised by all the members of the jury, the lead project with its strong sustainable approach, not only reunited developers and local architects but also shifted the debate: the city as we know it today cannot be looked at in the same way again. The environmental approach, in a region where floods and cyclones are regularly leading news, is to become a priority for our urban analysis and practices. Again, one might say it is not new, yet one can wonder why it is not implemented. The student works were locally widely covered by the media, discussed in architecture firms, and by the general public on Facebook. Whether it had an influence on the consultation that followed three months later is difficult to ascertain.However, it definitively feels that the students felt empowered in participating actively in the debate. At a time where everyone has a say on everything and often without commitment, it seems crucial that the agents of change for tomorrow get educated in participation.

References

– Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Regional Profile: Gold Coast (Statistical Division), http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Previousproducts/307Population/People12004-2008?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=307&issue=2004-2008 [accessed May 2017].

– Bosman, C. & Strickland, J. (2015) “The Value of Place” in Mr. Gjerde & E. Petrovic (eds) Proceedings of UHPH 14 Landscapes and ecologies of urban history and planning, pp. 47-60.

– Boyd, R. (1960) The Australian Ugliness, Melbourne: F.W. Cheshire.

– Dupre, K. & Bosman, C. (2017) Development versus coastal protection: the Gold Coast case study (Australia) in Etudes caribeurbanennes, 36.

– GCCM (2006) Changing nature of the Spit and Broadwater, Information sheet 7, http://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/100925/GCSMP7.pdf [accessed 06/12/2013].

– Norberg-Schulz, C. (1980) Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, New York: Rizzoli.

Karine Dupre is an architect, teaching at Griffith University. She has a special interest in urban studies, and particularly in the interrelationships between Cities and Tourism. As an educator, she is passionate on empowering the students with critical thinking and comprehensive approach.

Ruwan Fernando is a lecturer in Parametric Design at Griffith University. He graduated in Architecture from the Victoria University and received his PhD in evolutionary design modelling from Queensland University of Technology.

Volume 1, no. 2 Summer 2017