Conflict, speech, and truth within the urban space of Tahrir square

– Rafik Patel

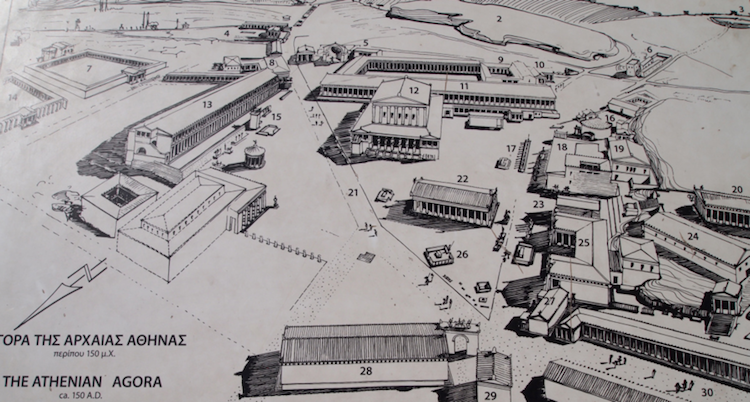

The Arab Spring began in December 2010, the catalyst being the self-immolation attempt of Tunisian citizen Mohamed Bouaziz (Lopez de Souza & Lipietz 2011, p.618-624) which lead to a wave of revolts throughout the Middle East. The world witnessed a public rebellion and spectacle of social and political force. It sparked a new age in the Middle East, one where citizens began to revolt against governmental economic policies and power; it was a political and cultural phenomenon that spontaneously grew throughout the region, and as Henri Lefebvre (1996) argues, citizens began claiming a Right to the City. Public spaces became a political arena whereby conflict was witnessed and confronted. In the case of Cairo Egypt, Tahrir Square acted like a classical Greek agora. Marcel Detienne (2001) argues pre-political thought was established within Greek the agora. It was a place where warriors assembled for the ‘clash of discourse.’ The space of the agora is considered to be a shared space ‘held in common’- an arena of a collective self-awareness, fair and completely open in its proclamation – a place of unveiling the truth. Within the Greek polis the Agora as an ‘open’ place for the warriors to gather and discuss strategies, and challenging politics. Detienne believed the practices of the Greek warrior, ‘constructed and shaped, both spatially and symbolically,’ a public place that we can call ‘the place of the political’ (ibid, p.45). Later the Agora also became a space to discuss science, culture and so forth. As the citizens’ stage set for democracy, the Agora is also space where symbols of power come together; the monumental buildings and statues surrounding the agora represent the authority of the State. Despite this presence of State authority, if space is ‘open,’ democracy is also always present in it (Jenks 1987). This paper examines how the architecture and ethos of the Greek agora explained by Detienne manifested itself in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, and how space and events facilitated the manifestation of the ‘warrior’.

1. Map at entrance to the Athens Agora (Courtesy of Cathy Dutchak)

The Egyptian revolution began in January 2011, the citizens of Cairo started the occupation of public space in the city, most striking being Tahrir Square (also known as Liberation Square). Tahrir Square was built during the nineteenth century and originally named Ismailia Square after President Khedive Ismail, whose reign lasted from 1863 to 1879. The square has a history of revolts: amongst them the first violent protests in 1919 against the British occupation, which gave rise to Egypt’s independence in 1922, and, in 1952, against the rule of King Farouk. As a result of these two successful uprisings, President Gamal Abdul Nasser (term 1953 to 1970) renamed Ismailia Square to Tahrir Square in 1955 (Tahrir meaning liberty in Arabic). During President Hosni Mubarak’s rule (1981-2011), he also proposed a so-called ‘enlightened policy’ that was to counteract the so-called ‘dark’ Islamist activists (Abaza 2010, p. 34), and accompanying campaign was titled ‘A Hundred Years of Tanwir’ (Tanwir meaning enlightenment in Arabic). While claiming enlightenment, the Mubarak government, however, took disciplinary action against anyone demonstrating against inadequate salaries and a worsening economic situation. Effectively placing a limit on how space can be used. Thus, for many years, a confrontation was mainly avoided since many thought it was ‘better to tolerate the current regime and maintain the status quo than to aspire to change that is unknown’ (ibid). This way, at least, they knew whom they were dealing with. Although Mubarak’s government possibly presented Egypt with a new image of itself, it is evident that the concept of enlightenment was used only for propaganda purposes and the implementation of a genuinely democratic system was not carried out. However, On Tuesday 25th of January, known as the Day of Revolt, protesters rebelled against a total deregulation of working conditions, unemployment, inflation, and the thirty-year repressive governance. Through the course of these political changes, the Square has also changed. Its size has decreased and has transformed into a circular roundabout for vehicles. Strangely though, this reconfiguration of its geometry provides a radial centre much like that of the agora and suggests a space that can be protected/barricaded from attack.

Mobilisation and Open Border Land

Detienne believed the agora was a place considered ‘common’ – a space of a collective self-awareness – egalitarian and a setting for the proclamation of justice; organised like a court built for public trials. Hence it was an arena where laws passed and the establishment of the saying ‘we, the city,’ or it pleased the council or the assembly’ established (Detienne 2001, p.45–49).

2. Tahrir Square, Photograph: Johnathan Rashad (Courtsey of Creative Commons)

It is the protesting, the impromptu occupation of public spaces, that is significant–conversations and discourse/dialogue that are spontaneous to promote discovery and stance for current situations; it is the spectacle that registers revolutions (Hannah Arrendt 1990). Although the purpose of the revolution is to bring down the regime, it’s imperative nature was to bring people together (to share) in public space an establish order without coercive authority. Today this is in its self a test if borders (physical and ethical) controlled by governments can be permeable or open. Even if is there is no political result; there is an energy created with the will to challenge the control of space by collective agreement. As with the Eighteenth-century French Revolution Enlightenment, the free contest to shape the development a new public space. In the case of a contested heritage, the Agora is the space that is open and where a proclamation is voiced for deliberation and making decisions. The ‘warrior’ (Detienne 2001, p.45) or collective body, comes to declare its position at the centre. Lefebvre argues, ‘what the eyes and analysis perceive on the ground can at best pass the shadow of a future object in the light of a rising sun’ (Lefebvre 1996, p.148). Hence space needs to be open to horizons, and can only develop with the inclusion of social practices of urban society.

For the major part, Tahrir Square had been closed off for years with the intent of preventing public assemblies that would hold space hostage. During the revolt, the removal of physical borders by the public allowed the reclamation of the space that insisted reform. In this way, this paper argues that the crowd transformed the boundaries of Tahrir Square allowing its spaces to be more open and full of spontaneous events (Sennett 2008). Thus, removing the area of exclusion, allowed the crowd to promote not only a way in but also a way out (Kant 1784). The openness and flow of digital space via social networking and blogs encouraged critique of the status quo and activated smart mobs (Rheingold 2002). It allowed crowds to mobilise, rally, organise the demonstrations and created a platform to publicise the on-ground events taking place within the revolutions. Sites such as Facebook and Twitter provided an alternative voice to State lead propaganda seen in mainstream media. When the government realised how this public domain was gathering empathy and becoming mobilised, the internet and mobile communication networks were closed down for several days. However, once the protests were on the ground, both virtual and physical groups proved to be unstoppable. Known as the ‘Paris of the Nile’ (Alsayyad 2011), the design of the city, inspired by Khedive Ismail’s Parisian friend’s Baron Haussmann (who carried out Napoleon III 1950’s urban renewal plans of Paris), also enabled the occupation of Tahrir Square. The boulevard and square layout- included two bridges leading to the square, several adjacent spaces with twenty-three streets that lead to different parts of the square meant that it was impossible to stop the movement of the crowd. During the protests, fences that had closed off the urban public space were taken down and used as protective barricades from the military and pro-Mubarak supporters. In this way, the crowd reconfigured the spatial and political boundaries from one of exclusion to an open and new internal borderland filled with a programme of necessities for living through the revolution. A community was set up that Included within the space a series of zones with different functions: a media station, a campsite, a kindergarten, a pharmacy, clinics, a water station, food stalls, an ablution area, a stage area, flag-selling stalls, a recycling area, a memorial space, a prayer space, and an art space. This social organisation of Tahrir Square produced space that is egalitarian and open – an agora where bodies accumulated in an urban arena for speaking, deliberating, creating and critiquing. A community not based on age, religion, sex, or gender, but one with a shared outlook demanding equality and a better future.

Space for Public Dialogue

According to Henry Lefebvre, citizens have a ‘Right to the City’- a right to urban life. He argues inhabitants have the right to change themselves by changing the city. Lefebvre acknowledges the possibility for cities to radically restructure its configuration of political social and economic platforms whereby power transfers from state control to the urban inhabitants that would lead to urban reform. Therefore, urban space is considered active in its production, it is not static, and it is the experience that creates ‘lived space.’ Testing social relations and politics are necessary rights of citizens to transform urban life.

The Cairo revolution had its agency through the collective. It was a time for intuitive knowledge and political thought to be expressed throughout dogmatic regimes freely. Time for waiting was over- it was prudent for civic culture to claim its pride, the Right to the City was felt ‘like a cry and a demand’ by the public (Lefebvre 1996, p.152). Within the city, any encounter of resistance or anarchy was constantly kept in check through aggression imposed governmental authorities. Although the modern Arab state claims authority derives from the ‘people,’ it was not until the revolt that the collective voice for an ethos of change was being heard, acknowledged and felt. It was a time ‘of the people.’ It is interesting to note that the revolt was not demanding a particular leadership, but rather calling for a clearing out of the current political system – a form of will for truth and justice. In the past, the concept ‘of the people’ remained as a defensive mechanism, but now it had taken up an offense as a legitimate force. Thus, the Right to the City whereby a new imaginative government radically be inclusive of modern world issues and addresses the needs and desires of all demographics were being demanded (Lefebvre 1996).

In this milieu lies a type of space whereby models of power are challenged. It is the agora, as Detienne states, a ‘space of the warrior’ (2001, p.45). An agora is a place for free spoken word, or ‘rhetoria’ expressed by the ‘rhetores,’ to be held by the ‘dimos,’ who together adjudicate an outcome. Detienne suggests that the origins of Greek agora refer to the location where individuals hold assemblies’ pronunciation of speech, and in both the singular and plural, signifies ‘clash of discourse, debates that take place in the assembly’ (ibid). Neither in the epic Iliad and Odysseus or elsewhere is the agora a place for social formalities, nor space for a private conversation but rather an open debating forum for the crowds’ affairs with Themis opening and closing the space. In Odyssey, the speech within the agora addresses both military and public affairs.

Illuminating Social Truth

With the Cairo revolution, human life found itself in a contested field of such an ontological milieu, where a duality of power needs lies in balance for the openness of public space. With the accumulation of bodies working with a common agency, space of unpredictable action was met with hostility and ultimately violence from Pro-Mubarak supporters and state force, and a ‘space of the warrior’ manifested itself within the ‘place of the possible’ (Lefebvre 1996, p.154). This clash presented a place for ‘critique’ and ‘dialogue’ (supporters, but also through the transgression) illuminating a truth on the social situation of Cairo (Foucault & Kritzman 1990, p.123). It is an example of how through discontinuity, we can illuminate the nature of the space. Michel Foucault suggests that a population can free themselves from the darkness of imposed political and economic shadows through a form of transgression if a set of events is put into motion. Advocating political change ‘in order to determine what can be known, what must be done, and what must be hoped’ (Foucault 1984, p.38). In the Classical Greek tragedy that presents the dark underground of human existence, darkness being a power opposed to light; however, light is not defined as the opposite of darkness; rather, in the presence of light, darkness is destroyed and overcome with an unrelenting bright light. A visible light that illuminates’ truth and the inner moral self-evidence, proving darkness is ontologically inept.

The notion of Alētheia or the illumination of truth emerged from Classical Greek thought and organised around the philosophy of metaphysics. An understanding of both religious thought and the philosophical thought gave way to the transition from myth to reason, and political thought was matters that were of interest to a group were laid out in the centre, not for judgment or deliberation but was important to be heard and felt. For the good of the city, the agora was a place for dialogue between individuals and between the State and the Public. The public reflection of the state of affairs produced warriors that acted on behalf of the democratic (Detienne 1996). Hence, the events that play out in the urban space of Tahrir Square activates a proliferation of questioning knowledge and truth. One might say that this is a form of illumination that ‘creates the overwhelming, conspicuous clarity with which the real ‘comes forth’ (Blumenburg, 1993, 31).

3. Sunrise in Tahrir Square, Carlos Latuff (Creative Commons)

According to Francis Bacons’ lumen experientiae, the act of experience can be ‘light.’ A new epoch is created that is not universal but rather a force of self-realisation, only experience ensures the obtainment of pure direct knowledge (Suhrawardī 1999) occurs through the individual’s ability to witness the ‘illumination’ of reality of that which is to be defined – a face-to-face encounter needed- a revolt. Expressed is a metaphor for the method of progress for creating a ‘greater common world for all…not a momentary act, but rather a historically continuous path of discovering the truth’ (Blumenburg 1993, p.39). In contrast to the Middle Ages where truth was considered self-luminous, truth does not reveal its self; ‘natural luminosity cannot be relied on; on the contrary, truth is of a constitutionally week nature and man must help it back on its feet by means of light-supporting therapy’ (ibid, p.52) – truth must be revealed.

Conclusion

The Egyptian uprising was a phenomenon that was witnessed across the globe. It was not imposed by such way of a political party but through public/civic collective gatherings. Agency and activism demanded democracy – time for waiting was up- it was well overdue- civic culture required change-it was their right. This movement, not restrained by a ruling state that administer techniques of social order, called for culture of dialogue between citizens and a forced dialogue with the government, The revolution opened a forum for new knowledge and civic pride inclusive of a new generation. A significant strength of the revolution was its ability to mobilise via its urban and digital space. Its ethical ethos quickly spread through social media platforms and media coverage. Once bodies gathered on the ground, the spectacle of the revolution – it’s marching, the occupation of urban spaces, and violence shocked and captured its viewers. Tahrir Square, operating like the Greek agora, became a stage set where a visceral atmosphere was constructed. The citizens as its ‘warriors’ fought for the contestation of space, politics, and freedom – a true vision of its-self needed to be made visible and the affect resulted in dramatic effect. Social borders that had previously been closed, they were now permeable.

Following the successful revolt (resignation of Mubarak), an unprecedented event occurred where the public again rallied together to participate in their civic duty to clean up the debris left from the occupation. Since the 2011 Revolt, there have been continued protests within Tahrir Square. Thus, reassuring that this public space is still ‘open’; emphasising the importance Detienne attributed to the Greek agora, as a place of democracy – that public space/space of the warrior, should be open to accommodate assemblies in all their diversity, is still pertinent today. It is once again a place of speech that absorbs energy from its crowd and its history continues to hold firm that it is a symbolic space of liberation for the people Cairo.

References

– Abaza, M. 2012. The Trafficking with Tanwir (Enlightenment). In Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, [online] Volume 30(1): 32-46. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2535527/_The_Trafficking_with_Tanwir_Enlightenment_ [Accessed 18th April 2016].

– AlSayyad, N. 2011. Cairo: Histories of a City. Cambridge Massachusetts & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

– Arendt, H. 1990. On Revolutions, New York: Penguin.

– Bamyeh, Mohammed. A. The Anarchist Philosophy, Civic Traditions and Culture of Arab Revolutions. [online] Available at: http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/187398612×624355?crawler=true&mimetype=application/pdf [Accessed 10th March 2016].

– Blumenberg, H. 1993. Light as a Metaphor for Truth: At the Preliminary Stage of Philosophical Concept Formation. Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision. England: University of California Press.

– Derrida, J. 2000. Of Hospitality. California: Stanford University Press.

– Detienne, M. 1996. The Masters of Truth in Archaic Greece. New York: Urzone Inc.

– Detienne, M. 2001. Public Space and Political Autonomy in Early Greek Cities. In M. Henaff & T. B.Strong ed., Public Space and Democracy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

– Foucault, M. 1984. What is Enlightenment? [online] Available at: http:/philosophy.eserver.org/Foucault/what-is-enlightenment.html [Accessed 25th July 2011].

– Foucault, M., & Kritzman, L.D. 1990. Politics, Philosophy, Culture: Interviews and Other Writings, 1977-1984. New York: Routledge.

– Jencks, C. 1987. Democracy: The Ideology and Ideal of the West. In A.C. Papadakis (Ed.) The Architecture of Democracy, Architectural Design 57(9/10). London: Academy Group Ltd, 6-25.

– Kant, I. 1784. An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment? [online] Available at: http://www.english.upen.edu/mgamer/Etext/kant.html [Accessed 25th July 2011].

– Lefebvre, H. 1996. Writing on Cities. UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

– Lopes de Souza, M., & Lipietz. 2011. The ‘Arab Spring’ and the City: Hopes, Contradictions and Spatiality. City: analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action, Volume 15 (6), London: Routledge. Available at: http://abahlali.org/files/B8579d01.pdf [Accessed 30th Janurary, 2017].

– Patel, R. 2011. An Opening of Tanwir. Journal of Architecture and Related Arts: Interstices 12 Unsettled Containers, p. 114-119.

– Rheingold, H. (2002). Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing.

– Sennett, R. (2008). Quant, The Public Realm. [online] Available at: http://www.richardsennett.com/site/SENN/Templates/General2.aspx?pageid=16 [Accessed 12 July 2011].

– Suhrawardī, S. 1999. The Philosophy of Illumination. Utah: Brigham Young University Press.

– Trombadori, D., & Foucault, M. 1994. Interview with Michel Foucault. In J.D. Faubion ed., Michel Foucault – Power: Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984, Volume 3. New York: The New Press, p. 239-297.

+

This article has been developed from a non-refereed article: Patel, R. 2011. An Opening of Tanwir. Journal of Architecture and Related Arts: Interstices 12 Unsettled Containers, p. 114-119.

Rafik Patel is a Lecturer at Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand. His research examines urban spaces and how they are politically charged when revolutions such as the Arab Spring of 2011 gave rise to occupation of public squares. Concurrently he is also exploring the work of architect Lebbeus Woods, in particular to how his drawings are a mode of political activism expressing the nature of polemical situations around the world, and also is examining how a spatial exposition of memory (photographs, oral stories, and family archives) can depict and re-imagine the spaces of culture.

Volume 1, no. 4 Winter 2017/18