Decoding mapping as practice: an interdisciplinary approach in architecture and urban anthropology

– Carolin Genz and Diana Lucas-Drogan

-

Abstract

One can observe a renaissance in architecture, art and urban anthropology as in other cross-disciplines, rethinking the concepts of maps and cartography to capture the perceptions of the urban everyday. Moreover, academic as well as non-academic disciplines with a research interest in urban settings are facing methodological challenges when finding ways to visualize and analyze urban everyday life, its social and spatial connections to meaningful places for urban actors, and broader critical discussions on the power relations of maps. The article provides insights into the perceptions of mapping as a methodological tool in urban anthropology and architecture. Furthermore, it contributes to the methodological development of thinking beyond our very own disciplinary boundaries – which is not only connected to “terms” but focuses on the didactic mediation how mapping tools can be used. With a critical approach we elaborated a narrative of rethinking of mapping as practice to overcome the current boundaries of perception and mapping in anthropology and architecture. Therefore, the article provides a collaborative and interdisciplinary didactic concept and mediation on “mapping as practice”, which reflects our own position and decodes the seen and unseen of our research – by showing examples from our workshops and collaborative work.

MAPPING IN ANTHROPOLOGY

Mapping as a qualitative research method

The main systematic research technique of urban anthropology is ethnography and its holistic approach to understand people within their social, spatial and cultural contexts. Ethnography provides a toolbox of various qualitative methodological approaches, for the analysis of spatial practice, like field notes, participatory observations and qualitative interviews. Urban anthropology is constantly focused on “urban everyday life”, its logics, patterns and concerns. Therefore methodological approaches need to concern themselves with “spatial practice”.

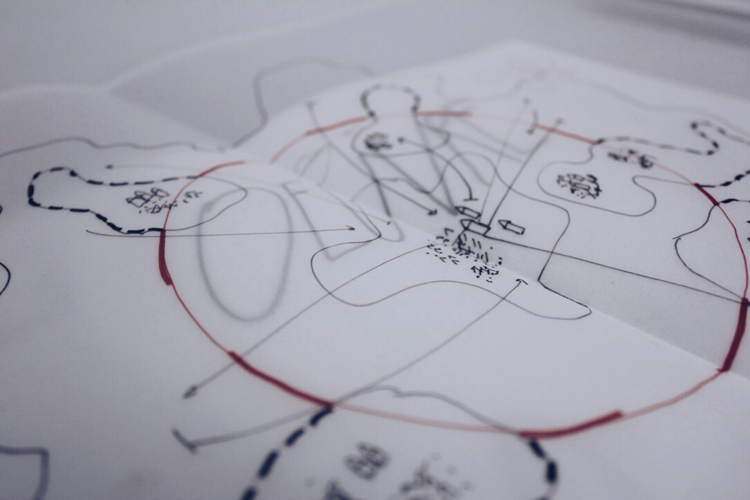

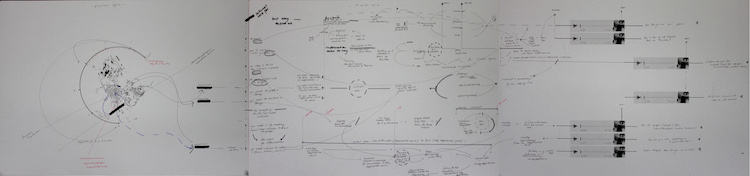

1. Ethnography in Urban Settings, Mapping the Urban Everyday. Urban Ethnography Lab, Workshop Toronto © Carolin Genz, 2017

Mapping can be used as a research tool to make social and spatial practices and the interactions in space visual and tangible. By visualizing spatial practice and interpreting a map, researchers can experience data that they were not even aware of. Additionally, we generally understand mapping as a process during fieldwork and urban research to discover, structure and highlight the spatial and social interactions and point out the blind spots, all of which one might not be able to capture by writing field notes, doing participatory observation or qualitative interviews. The map is one piece of data used to make the invisible (or the obvious) visible. With this kind of urban ethnographic data, one can return, reflect, and enhance awareness of a context for agreements, conflicts, negotiations, misunderstandings, power relations and accountabilities in the field of urban research. As cartographer Dennis Wood points out, mapping can be understood as an act of creating and imagining space and is therefore a powerful tool for the production of space (1992, 2010). For Wood maps are an accumulation of multi-layered stories about one neighbourhood, for example about its social class or cultural rituals. They tell stories of how we understand and define the places we call home (2012). Our dialog at the intersection of anthropology and architecture was the starting point for developing a deeper understanding of mapping as a practice.

Mapping in Urban Anthropology: Cognitive Mapping

Imagine a white sheet of paper and a pencil, lying just in front of you. Please draw spaces and places that matter for you the most and how they are spatially connected to each other. To be specific, urban anthropologists understand the method of “cognitive” (mental) mapping as a technique to generate a (two-dimensional) representation of spaces and places of the actors and their relation to each other. Cognitive mapping therefore, gives us a chance to get access to the spatial ideas and connections we might have in mind while thinking about specific meaningful spaces and places.

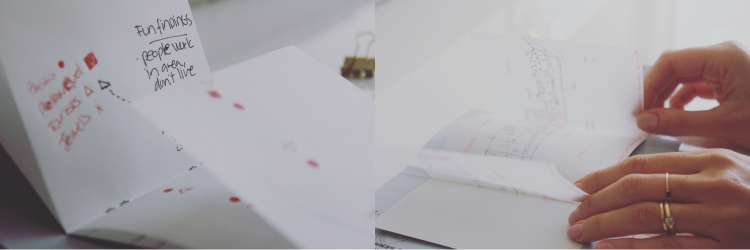

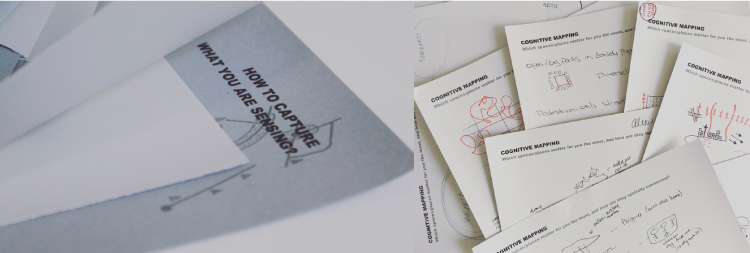

2. Cognitive Mapping Exercise: “How to capture what you are sensing?”. Urban Ethnography Lab, Workshop: Ethnography in Urban Settings © Carolin Genz, 2017

Mapping was one of the basic methods of the Chicago School, the birthplace of urban research studies (Lindner 2007). As Lindner points out, they used mappings to uncover emotions connected to urban space (2007). Its very approach was to capture symbol systems of actors. Therefore, mapping can be understood as “readable text” (Greverus 1972, 1994), which deals with culturally shaped perceptions of space and its usage, as well as identity-forming processes of urban everyday life (Greverus 1972). Hence, cognitive mapping in urban anthropology helps us to gain access to interpretations of symbolic structures of the city (Greverus 1972, 1994).

We understand a map as legible “field-notes” and logically as one piece of “urban data”. Cognitive maps help us to gain access to the spatial and social structures of the urban fabric and identify the meaningful spaces and places of districts and neighbourhoods as well as one’s own blind spots. Overall, a cognitive map is an “artefact”, which helps to reduce the complexity of “urban knowledge” and capture subjectively experienced live worlds as a whole (Ploch 1994). To conclude, cognitive mapping leads us to the question: How is (urban) space constituted? Tools for urban anthropologists (or sociologists, geographers, urban planners), to structure and visualize qualitative urban data of sensing the meaningful spatial structures of actors, need to be developed. Therefore, it is interesting to look into the field of art and architecture.

MAPPING IN ARCHITECTURE – A CRITICAL APPROACH

In architecture, map making is a common technique bound by cartographic view. The cartography of a certain territory is often a component for a planning strategy, which is the basis for future planning decisions. The techniques of visualization and experience with visual languages often have shortcomings when it comes to dealing with qualitative data like interviews, participatory observations or qualitative field notes. Architects have to learn how to explore their knowledge base and bring them into a critical-methodical working ethics. This research ethic is a tough challenge. The creation of data is a fragmented mixture of observations, interviews, notations, CAD plans and visual representation. With the danger of being seduced by the beauty of aesthetics, data material needs a critical mapping turn in architecture to get an understanding of the ethical use of qualitative data and the suspicious believe of objectivity. Architects need to be cautious not to reduce the aspects of the lived space and actions in society to simple choreographies. When using CAD plans generated from photographic footage or predefined plans, architects should reflect more on the “colonized” footage they are reproducing. The sources of data material to make two-dimensional site plans always put lead to a struggle in terms of the perception of actual space and the revisiting of the data footage. “For whom I am drawing? What do I hide? And what do I reproduce?” are questions that should be added to the ethical position of an architectural visual language and during research. The critical mapping turn in architecture should be based on qualitative research to enable the visual and even performative production of map making to become a critical and sensitive tool for spatial research and practice. The practice of counter mapping, which was formulated by the geographer Denis Wood, can assist architects and artists to develop a critical mapping approach.

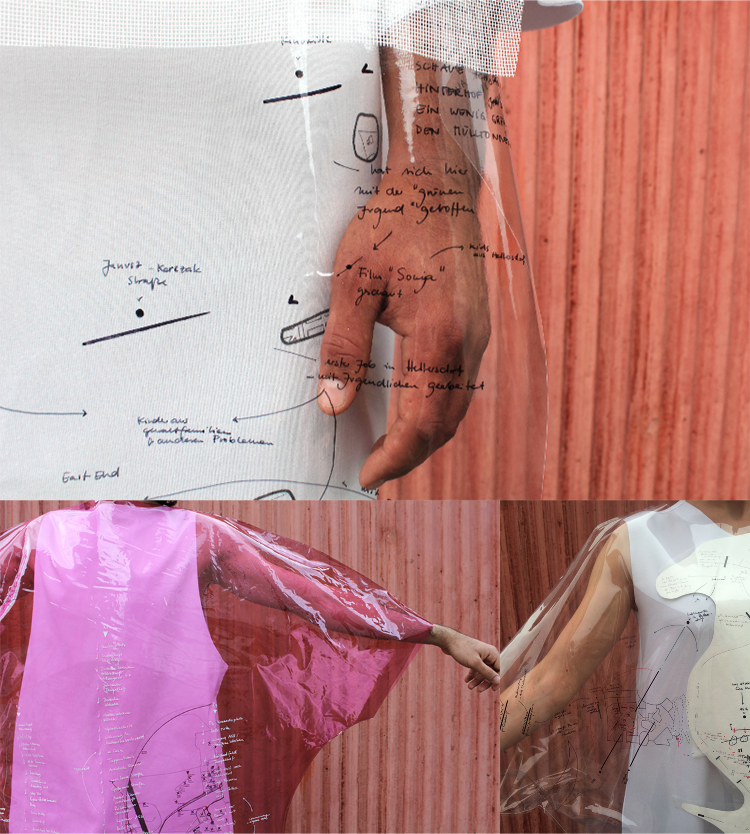

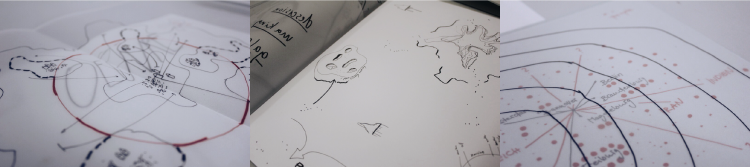

3. Emanzipierter Schutzraum, Emanzipierte Stadt, © Diana Lucas-Drogan, Vienna 2014. Critical Mapping Installation about the refugee protest movement in Vienna.

Counter Mappings – a critical mapping turn in architecture

Denis Wood offers a genealogy of “counter mappings”, which refers to efforts of mapping “against dominant power structures“ (Wood, 2012). In our understanding, counter mappings deal with visible authorship to clarify for what purpose the map was actually created and what information the map might hide. The dialog and communication between the map and the recipient immensely influences the understanding and usage of a map in our further work or research. The perception of the map is also a question of its media. How is the map displayed and what media do we use for it? Architects always get into trouble when rethinking their artistic output. Design and art, in their wider practice, help to delimit the boundaries of flat-drawn maps. Critical Counter Mapping practice has to be extended by the use of ethnographic research methods and the critical-sensitive use of the media to develop questions of how mappings can be communicated and transformed. Design, art and anthropology support the calls for a critical mapping turn in architecture. Hence, it is a tool of empowerment to put the struggle into a form of a constant dialogue. Demands, which haven´t been on the map or radar before, pop up on physical and digital maps and become a basis for negotiation. Agents of “minor” political struggles and resistance need the counter map to construct a common piece of statement for further discussions and plans. Counter mappings use this knowledge and look for new methods of how to make authorship, purpose and audience visible. Counter mappings are very often used for social and political conflicts and forms of resistance.

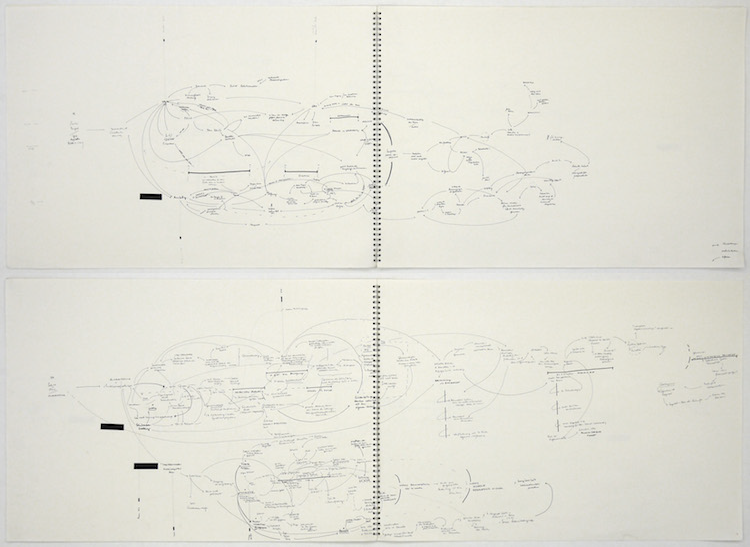

4. Haut von Hellersdorf, Diana Lucas-Drogan, Berlin 2017. “Die Haut von Hellersdorf” is a collaborative Counter Mapping of the socio-political life of refugees and locals in Hellersdorf. This picture shows Hellersdorf on the move and in transformation © Diana Lucas-Drogan, 2017

The methods and terms of “cognitive mapping” and “counter mapping” can be understood as frameworks and guidelines to think about our very own research practice, methods and perception of urban settings and our approaches to visualize urban dynamics. How can we implement these terms into our work within a critical and reflective approach? Open questions on authorship, producer, and visualisation helped us to foster and develop a didactic mediation of cognitive and counter mappings into our research methods, to focus on collaborative and interdisciplinary transfer of knowledge and skills, as well as exchange of expertise between urban anthropology and architecture.

5. Whats-App Mapping © Diana Lucas-Drogan, Berlin 2016. Notation and Mapping of the Stop Deportation Group fighting against deportation in the deportation center at Eisenhüttenstadt, Germany. The Interview was recorded by Whats-App and shown in a Videoperformance at the HKW, Berlin.

6. Wiederaufnahmeprobe – Berlin Field Recodings – Mapping along the Refugee Complex, Berlin 2015. Interview Mapping with Martin Düspohl (director of the Kreuzberg Museum) and Sabine Horlitz / Oliver Clemens (AnArchitecture) about the refugee protest at Oranienplatz and the meaning of Critical Mapping. Photo © Cristian Hanussek

A COLLABORATIVE METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH: DECODING MAPPING AS PRACTICE

We want to develop a critical approach and elaborate a narrative of rethinking mapping as a practice. We want to provide a concrete approach of how to overcome the current boundaries of perception and mapping in anthropology and architecture. It is therefore important to decode the process of mapmaking as practice in order to overcome our very own bias as authors and mapmakers, to produce new perspectives, urban fabric and data, and levels of reflection. What possibilities do we have to think beyond the given methodological tools? Rereading our anthropological and architectural approach towards an urban, critical mapping practice, we figured out five key components. Our Practice is: (1) involved, (2) conceptual, (3) inventory, (4) ethnographic and (5) processual. The Decoded Mapping Practice, developed during the Summer School at the Georg-Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies in 2016, needs the formats of lectures, exercises, fieldwork and discussions to generate an oscillating discourse of the production of critical maps. Generating a practice that reflects one’s own position, decodes the seen and unseen of our research.

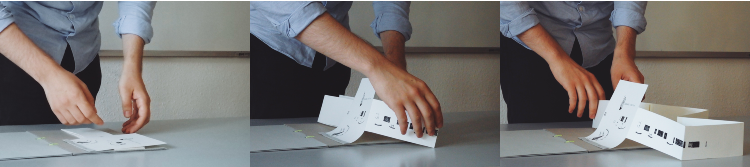

7. Decoding Mapping as Practice, Mapping Workshop. Summer School “Metropolitan Studies”: Rethinking Berlin’s Housing Question. Georg-Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies, Berlin 2016. Photos © Carolin Genz, 2016

Decoding Mapping as Process: The state of being “involved”

Walking through the city and trying to capture its hidden symbolic logic, cultural, social and spatial codes is strongly influenced by our own attitudes, perceptions and attributions of meaning. The way we are socialized influences how we sense the city, and collect and produce urban data. Finding tools to structure and materialize our own sensing through creative ways of visualization (e.g. with mapping) is one approach to find the blind spots and culturally meaningful spaces and places in an urban context. How can we uncover the knowledge people already incorporate and their perceptions of the city? In sensing, the urban, the body, and the subject are involved. Scanning and observing is a very active part in ethnography and a method of map making. Our selection depends on our knowledge, recent readings, and our research questions. As researchers we influence the field directly through our presence and behaviour; date, time and weather conditions impact our data selection enormously. Mapmakers who use their body to measure the field seem to become an abnormality. Did you ever try to measure the urban space with your body? In the production of maps, we are always involving our body, expectations, and various moods – ourselves. This is something we have to be aware of early on. It is a central methodological approach of ethnography, specifically in “participatory observation”: one is always part of the research and one cannot get away from oneself. Being aware of one’s own involvement is necessary for reflecting and rethinking one’s own mapmaking practice. Within our collaboration, we want to provide a didactic mediation on finding ways to sense and capture the urban fabric.

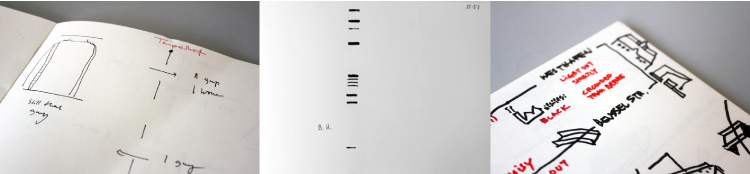

Involved – Mapping the Unmappable?

The important start is to teach the drawing technique of map-making, in which the author becomes the medium, e.g. to draw a non-territorial map to realize the cultural based criticism of ownership and power-relations in an urban settings nowadays. In going along with this, the technique of hand drawing made the author/drawer sensitive to how to highlight, hide and position a certain intention or story they wanted to communicate. Bringing the housing question, for example, into a future scenario shifts us away from the territory we are based within and helps us construct new forms of spatial criticism and observations. Within this session we started to re-read our drawings to practise the concept and the intention of our construction and to be aware of the construction of the line, we use to draw a map. Mapping the unmappable allowed us to avoid prescribed representation issues and to build up our own drawing language.

8. “Mapping the unmappable”. HUWISU International Summer School “Metropolitan Studies”, 2016. Rethinking Berlin’s Housing Question, Georg-Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies, Berlin 2016. Photos © Carolin Genz, 2016

Conceptual – the production of a map

Furthermore we have to think about concepts and the conceptualization of maps: Getting access to a critical mapping practice we need to dive in and get a closer look at the construction, structure and representation of maps. Questioning this, holding a lecture about the construction of maps is the first step. Starting with the basic layering for multiplied maps (title, scale, territory, legend and descriptions), we further focused on involving issues of our map production. Including the body, as identity and authorship, the lecture went through the topics of concepts, scripts, image composition, and media of the map. While dissecting the works by Iconoclasistas, Larissa Fassler and Mark Lombardi, the codes and displays of the produced maps help us to understand how many decisions have to be made, to layer and represent carefully. Looking at Maps from paper to performances and installations offers a genealogy of the media of maps and an opportunity to rethink the physical techniques of map production.

9. Haut von Hellersdorf, Berlin 2017. Color-Coded Mapping Installation and Mapping Performance for Haut von Hellersdorf, Kunst im Untergrund-ngbk, 2017, Photos © Matthias Neumann, Diana Lucas-Drogan

Inventory – Learning to Observe

Unlike an objective representation of a map the concept of an inventory mapping starts with observations and the collection of details. Therefore a drive-along with public transportation or a walk on one specific street or crossroads could be a starting point. During the Intentional Summer School “Metropolitan Studies” e.g. the participant took the one-hour S-Bahn (urban rail) ring, specifially know as the Ringbahn, starting at Berlin Ostkreuz. For one hour they observed common things and mechanisms, which they wouldn´t note in their daily practice. Things, one wouldn’t normally pay attention to, became the focus of observation – especially on the urban fabric.

10. “Taking the Loop”, Map © Elsie Chuang. HUWISU International Summer School “Metropolitan Studies”, 2016. “Rethinking Berlin’s Housing Question”, Georg-Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies, Berlin

11. “Taking the Loop”, Maps © Diana Lucas-Drogan, Karlis Ratnieks, Heewan Shin. HUWISU International Summer School “Metropolitan Studies”, 2016. “Rethinking Berlin’s Housing Question”, Georg-Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies, Berlin

Like the French writer Georges Perec, who developed a site-specific notation technique, (1974) we focused on one perspective for one hour – like the focus on sound, words, language, light or colour. The literary experiment was described by the author Hanns Josef Ortheil as “notating as registration” (2011).

Registering specific sights and times, the participant created an inventory of an S-Bahn scenario. The accumulation of details is the data for further map production is at the same time, in the rhythm and clusters, a poetic of the space. Thus, the first step getting into the field becomes part of the critical and reflective map production. The subsequent question is: How to handle the urban “data”? How to get access to the urban for further interpretation and a “thick description”, which can be used for further research analytics?

Processual – Map Making

Unfolding the City – The Materialization and Visualisation of Urban Ethnographic Data

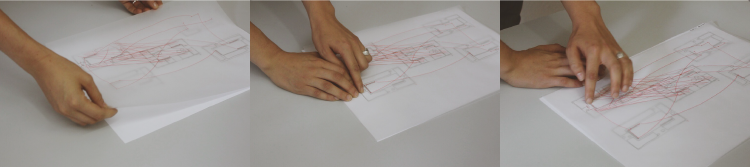

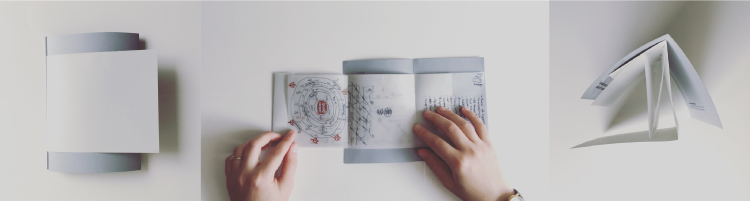

12. Unfolding the City, Fold-Up Mapping Booklet © Carolin Genz, 2017. Workshop “Ethnography in Urban Settings”, Urban Ethnography Lab, Toronto, 2017

Urban ethnographic data needs to be made material to make this knowledge accessible. One can write dense and reflective field notes, following the influence of Geertz’ Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture.” (1973) For some emotions in space and for our very own personal, individual perceptions, however, words might not be enough. Ethnography offers different possibilities and tools to capture a set of data by writing field notes, recording, and mapping. Therefore the „Urban Tool Box“ or the “Fold-Up Mapping Booklet” are useful examples and concepts for processual map-making and qualitative data collection. The box literally can be “filled“ with urban data while remaining tangible: one can feel and touch the data through this specific kind of materialization. Material gives a sense of form.

13. “Urban Tool Box”: generating ethnographic urban data” © Carolin Genz, 2016. HUWISU International Summer School “Metropolitan Studies”: Rethinking Berlin’s Housing Question, Georg-Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies, Berlin 2016

The “Fold-Up Mapping Booklet”, which was created during the Workshop “Ethnography in Urban Settings” of the “Urban Ethnography Lab” helps to unfold the complexity of the urban and provides the possibility of access to questions of urban while doing research. What could be other creative strategies in urban research to capture what you are sensing? The collaboration of mapping artists and architects can help to develop and enlighten the creative and visual blind spot in urban ethnography.

14. Urban Tool Box, International Summer School Metropolitan Studies, 2016. “Unfolding the Loop” © Karlis Ratnieks

15. Urban Tool Box, International Summer School Metropolitan Studies, 2016. “Weddinger Mischung”, © Heewann Shin.

The set of material tools (“Urban Tool Box” and the “Fold-Up Mapping Booklet”) helps to capture urban ethnographic data creatively and to achieve the scale of tangible visualization of this data. In that sense, the urban ethnographic data only becomes “thick” und unfolded in the following three layers:

-

Mapping by drawing spatial observations with the technique of Decoding Mapping as Practice as described. Mapping with different layers (of transparent paper) helps to visualize the different overlaying social dynamics of urban space. The technique of an “involving map” is based on the idea that the researcher is the author of this map while being involved in urban space and its social, cultural and political complexity;

Writing by structured field notes and words to describe the scenes one was observing and drawing on a map; and

Walking & Talking by using words and language to explain the collected data in the map e.g. with the Go-Along Method (Kusenbach 2003).

16. Right: “Fold-Up Mapping Booklet”: generating ethnographic urban data. UEL Workshop: “Ethnography in Urban Settings”, Toronto 2017. Left: Mapping Spadina Ave. Photo and Concept © Carolin Genz, 2017

17. How to capture what you are sensing?”. UEL Workshop: Ethnography in Urban Settings, Photo © Carolin Genz, 2017

Along these lines, the booklet is three-folded: Only by folding it up through our senses, we get access to the complexity of the perception of urban space. Only by understanding urban research as a process we are able to capture the complexity of urban life and research questions.

What do we want to do in the future?

Focusing on the question what could be creative strategies in urban research to capture what we are sensing, the new founded “Urban Ethnography Lab” at Georg-Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies in Berlin provides workshops to develop ideas and visions – in collaboration with arts, architecture and anthropology. Using this platform to reflect on established methods for thinking outside the box and not necessarily from an academic point of view, we aim to find didactic concepts to carry out creative approaches and empower non-academic actors. In the near future, we want to reflect on sets of terms of mappings to think about its practical advantage for current social and political questions on urban development and transformation processes. We want to ask methodological questions (as well as theoretical and production related ones) of mapping processes and provide creative ways of capturing urban phenomena with an interdisciplinary approach to provide a methodological access to the complexity of our urban society and living environment. The “Fold-Up-Mapping-Booklet” makes ethnographers and urban researchers sensitve to how they visualize their data. The technique of “decoding the process of mapping as practice” starts with a comforting text and counting methods, and helps to limit the “fear” of visualizing urban data from an architectural perspective, to raise awareness of qualitative data and research in the discipline. Building up one’s own map drawn by one’s hands and based on present field trips, researchers get access to scaling, formats and layers involved in the construction of a map. There is nothing given, everything will be constructed.

References

— Cosgrove, D. (2001), Apollo’s Eye: A Cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western Imagination. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

— Dodge M., R. Kitchin & C. Perkins (2009), Rethinking Maps: New Frontiers in Cartographic Theory. London: Routledge.

— Duden (2011). Schreiben dicht am Leben.

— Geertz, C. (1973). Thick Description. The Interpretation of Cultures. Selected Essays, Part I.

— Greverus, I. (1994). Menschen und Räume. Vom interpretativen Umgang mit einem kulturökologischen Raumorientierungsmodell. In: Dies. (Hg.): Kulturtexte. 20 Jahre Institut für Kulturanthropologie und Europäische Ethnologie. Frankfurt am Main, pp. 87-111.

— Kusenbach, M. (2003). Street phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 455-485.

— Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. Cambridge: M. I. T. Press.

— Obrist, H. U. and McCarthy, T. (Eds.) (2014): Mapping it out. An Alternativ Atlas of Contemporary Cartographies. Introduction. New York.

— Perec, G. (1974). An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris.

— Perkins, C. (2009). Performative and Embodied Mapping. In: International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. pp.126–132. Manchester, UK.

— Pickles, J. (2001). A History of Spaces: Cartographic Reason, Mapping and the Geo-coded World. London: Routledge.

— Watson, R. (2009): Mapping and Contemporary Art. In: The Cartographic Journal. Vol. 46 No. 4 (Art & Cartography Special Issue). pp. 293–307,

— Wood, D. (1992), The Power of Maps. New York: The Guilford Press.

— Wood, D. (1993). The fine line between mapping and mapmaking. Cartographica, 30. pp. 50–60.

— Wood, D., & Fels, J. (2008). The natures of maps: Constructions of the natural world. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

— Wood, D. (1992). How maps work. In: Cartographica, 29 (3&4), Autumn/Winter 1992, pp. 66-74.

— Wood, D. (2010). Rethinking the power of maps. New York and London: The Guilford Press.

— Wood, Fels, J. (1986). Designs on signs/myth and meaning in maps. Cartographica, 23, 54–103.

The starting point for this collaborative work between the authors began in Summer 2016, while the urban researcher and anthropologist Carolin Genz was the academic director for the International Summer School “Metropolitan Studies: Rethinking Berlin’s Housing Question”at the Georg-Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies at Humboldt-University. During the Summer School we therefore focused the political debates, the grassroots movements and the practices of the everyday life of various actors in this field of urban development and how they cause, effect and influence the dynamics of urban societies and in this way shape and develop urban transformation processes. Together with the artist and architect Diana Lucas-Drogan the summer school combined the principles of qualitative social research and the science and art of map-making, based on local field research.

Carolin as an urban anthropologist experienced the limits of the production of maps by the common use of mental or cognitive maps and is currently working on creative concepts of methodological approaches in the academic research field of urban anthropology and human geography in relation to how we capture what we are sensing and what tools can help to materialize and visualize urban ethnographic data (“Unfolding the City”). She is founder of the “Urban Ethnography Lab” and started to work/collaborate with Diana, who practices the notions of map-making since 2010. Based in the field of architecture Diana missed the scientific – qualitative methods in architecture and the arts.

Volume 1, no. 4 Winter 2017/18