Landscape as a mediator between mining and urbanisation: the case of Minas Gerais and Nova Lima, Brazil

– Patricia Capanema Alvares Fernandes

In Minas Gerais, centuries of resource extraction have resulted in a palimpsest landscape imbricated by layers of human settlements, mining and agriculture, continually interacting either in competition or symbiosis. By recognising this intertwinement, this article proposes to unfold the relations between urbanisation and mining in a historical-spatial perspective, seeing both as profound transformers of surface conditions and life. Through centuries, they have acted jointly in producing a landscape patched by mining pits and urban tissues, which deserves a thorough re-examination through more contemporary lenses of urban theory.

The last decades have witnessed the increasing fragmentation of the urban tissue along with the dissolution of long-standing dichotomies such as rural and urban, nature and culture. In the 1970s Henri Lefebvre (1999) referred to this phenomena as the simultaneous implosion-explosion of the city. It implodes (internally) breaking into disconnected fragments, and it explodes (outwards) in small detached pieces, spreading heterogeneous forms of urbanity across the rural landscape. Terms such as Cittá diffusa (Secchi, 2012) have emerged in the attempt to conceptualise this fragmented and heterogeneous urban form and, mostly, to categorically separate it from the modern city and the ones preceding.

In the attempt to find new methods to approach this complexity, going beyond the post-modern refusal to the contemporary city, the resurgence of landscape topics is remarkable, especially in the last decades (Corner, 1999, p. ix). ‘Landscape’ as we know it, is not a new idea – it dates from the Renaissance, as reminded by the geographer Denis Cosgrove (1985, p. 46). It has lately become a meeting ground for geographers, biologists, artists and sociologists with architects and urbanists that start moving their attention beyond the city. Hence, they extrapolate the limits of what we used to know as “urban”, by incorporating issues of water, agricultural production, ecology and even mining to the urban problematics. Likewise, many scholars have begun to move “Beyond the City”, which is by no coincidence the title of the recent book by architect and urbanist Felipe Correa (2016), who focuses on the diverse urban models associated with resource extraction in South America. His work starts therefore to make valuable associations between mining and urbanisation, a topic which this paper would like to amplify.

Mining territories are exemplary of the inapplicability of traditional urban analysis tools which dichotomise urban and rural, approaching the territory through sectioning and segmentation while narrowing down variables. Although mining is typically paired with the human resources of urban domains, it paradoxically settles in non-urban grounds, where agricultural and other broader colonies are most directly disturbed. Serving as an interface between nature and culture, landscape urbanism is an integrating discipline through which to examine the territory: a product of the interaction between human and natural processes. It therefore no longer refers only to garden planting or pastoral scenery but embraces fields such as urbanism, infrastructure and spatial planning alongside more known themes of nature and environment. Grounded by a global environmental awareness, landscape urbanism investigates the encounter of large-scale infrastructures (i.e. mining) with their surrounding territories, aiming to find compatible solutions. Moreover, the broad temporal dimension of landscape projects the territory as a medium of continuous ongoing exchange, particularly relevant for historical analysis.

The lens of landscape is used here as a mediator to analyse the historical relations between mining and urbanisation in territory of Nova Lima, a colonial mining town shaped by centuries of resource extraction. The city, today containing a population of over 80.000 inhabitants in 429 sq. km1, is currently under enormous urbanisation and environmental pressures, being in the expansion radius of Belo Horizonte’s metropolitan area – a state-built city designed to be the provincial capital of Minas Gerais at the turn of the 19th Century. Hence, such relations shall be seen in a historical perspective and also examined in its contemporary context. The reconstruction of its history through a spatial perspective shall allow viewing its landscape – an intricate network of nature, excavated pits and urban patches – as a direct product and producer of resource extraction. Combining both diachronic and synchrony dimensions of urban history, this historical spatial reconstruction will consider not only its current contemporary (fragmented) form but also encompass its three-century-long history of patched forms of mining, agriculture and dispersed urbanisation. Therefore, landscape becomes a fundamental medium that allows construing a dynamic portrait, able to envision, simultaneously, those three opposing dimensions – urban, pasture and mining – within one embedded landscape.

1. Location of Nova Lima and Minas Gerais in Brazilian geography. Source: the author

Eighteen-Century Precocious Urban Network

Resource extraction has not only influenced Minas Gerais’s toponym (General Mines). It also continues to shape its landscape: its revolved ground, built fabric, and people. Recent research on the network of colonial towns in this province (Paula, 2000; Moraes, 2006) have shown that it is possible to talk about an eighteenth-century colonial urbanity even before industrialisation. The economy historian João de Paula has demonstrated that modernity and urbanity are imbricated in eighteen-century Minas Gerais, having produced a socially mixed and productively diverse society, with complex bureaucratic structures, social mobility and intense cultural and artistic lives, densely populating this particular territory (Paula, 2000, p. 14). Later, the architect and urbanist Fernanda de Moraes developed a profound historical and cartographic body of research, shedding light on the geography of a particular colonial urban network established on the basis of resource extraction activities, and diversified with manufacture and cattle breeding. The analysis of this particular form of ‘urban scene’ should not, therefore, focus only punctually on villages and towns with their urban tissues but should embed these within their surrounding territory including mining, agricultural and commercial activities that equally constitute the landscape.

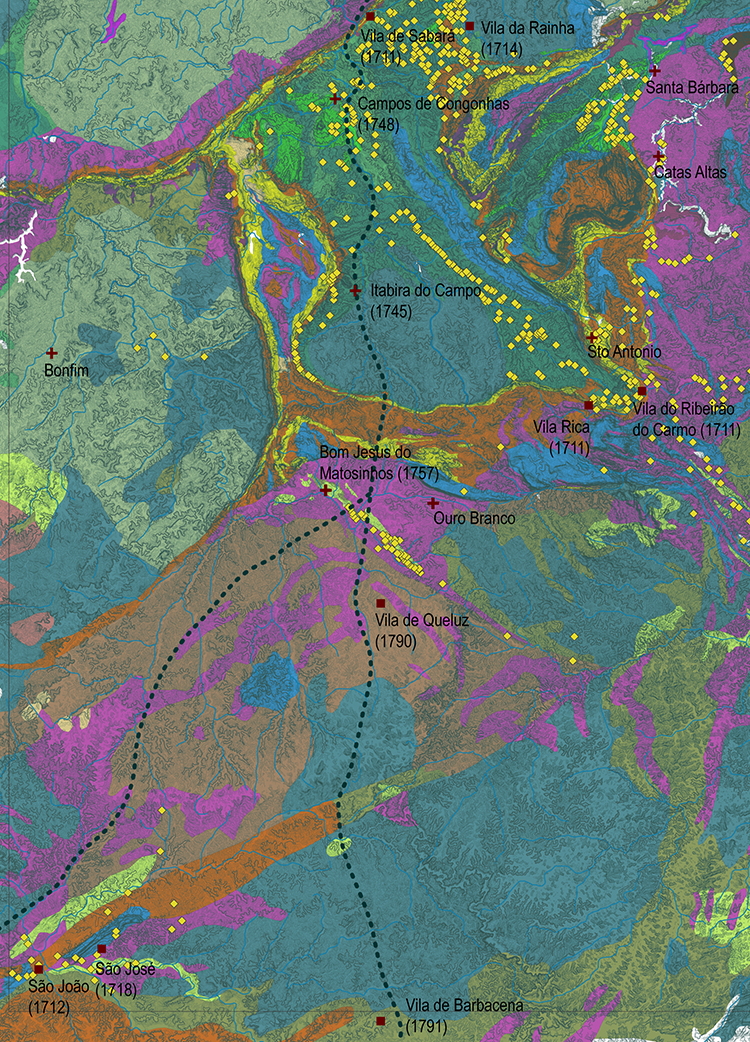

The (mining) history of Minas Gerais begins with the first historical documentation of the discovery of gold between 1693 and 17042. Since a large number of hands were needed for the gold extraction, a very diversified population flooded the mines, resulting in repetitive famine crises in the first few years. The urgent need for food production in combination with the instability of the mining cycles, induced a productive diversification around the mines, implemented by agriculture, cattle raising and diverse manufacturing plants3. Such diversification is a result of a combination of pure necessity and isolation. As the paths leading to the mines where closed – for better control of gold trafficking – and the transportation of materials by sea was difficult and expensive, the mushrooming of small manufactures was instigated. Alongside that, mines where usually in places of steep topography, another impediment to accessibility. The diversity and therefore resilience developed by Minas Gerais’ economy – having gold and diamond extraction as the nucleus of a dynamic market – is one of the leading arguments of Paula (2000) for considering its society intrinsically urban. The primary indicator of urbanity in the colony is still the unprecedented sprouting of human settlements in a short period. Soon after the first discovery of gold the village of Villa Rica de Ouro Preto (today Ouro Preto) was founded (1711) and after this a rapid increase in establishing villages (Vilas) followed. Many authors have concluded that the constellation of Vilas formed in the colonial period was strategic to the proper distribution of power and surveillance across the territory (Moraes, 2007, Paula, 2006, Lage, 2007).

Shifting from a geopolitical to a landscape lens allows one to also see other logics besides those considering politics and power distribution only. If one looks closer to the ground conditions, it becomes clear that the patterns of occupation are a direct result of geomorphological conditions and can be directly related to gold extraction logic. If one examines the relations between the paths and the urban constellations it becomes clear that only a few settlements are next to the main roads while others follow the gold, occupying narrow spaces with unique geological conditions. (Image 2) Alluvial gold, found in abundance in the many small rivers of Minas Gerais, meant highly fragmented and diversified activities. Owning a mine concession ranged in nature mean from camping at a prosperous curve of the river, alone or with two or three slaves to occuping larger pieces of land with many slave hands. The concentration of large amounts of gold in a relatively small territory (if compared for example to the sugar cane plantations in the north) meant, therefore, the fragmentation of land property4, with a direct consequence in fostering urban development and densification. Wherever there was a mining camp, it would soon develop into a human settlement, comprising of houses, small manufacturers, and markets. When the superficial gold deposits were exhausted, mining activity moved upstream leaving behind a chapel, a market, and some houses. Those were the sparkle of a new post-mining condition and started, very early, a succession of accumulative landscapes.

2. The paths, the gold mining towns and parishes of the 18th century and current records of gold occurrence. Source: the author with cartographic data by IEDE, MG and CPRM and historical data compiled by Moraes, 2007

Panerai (2006) has described the urbanisation patterns of hilly landscapes, like the one around Ouro Preto, as “the path and the hill” in which the urban form seems like a succession of roads around which the urban tissue grows. In steep topographies, these cities follow the ridge lines and valleys, flaking the canyons. As Villa Rica prospered, the city indeed came to occupy the sequence of small hills and narrow valleys around the Ouro Preto river, surrounded by mountains. However, the primary driver for shaping this landscape was indeed mining. The presence of gold in very narrow valleys and steep topographies boosted urbanisation in places which would have never been inhabited otherwise. While describing his impressions of Ouro Preto, the nineteenth-century French naturalist traveller Auguste Saint-Hilaire (1830) affirms that if it were not for the gold, it would have been impossible to find a less favourable location for this town.

The urban form of the Portuguese American colonial towns have been cleverly described by Sérgio Buarque de Holanda in the classical Raízes do Brasil as being a result of improvisation when compared to the grid model systematically applied in the Spanish America. While internal tissue is not what differentiates the mining towns, it is certain that the networked pattern in which these urban landscapes are shaped directly relates to the mode of production that serves as impetus: mining.

To approach contemporary urban conditions, characterised by horizontal sprawl, open-endedness, indeterminacy and change, Charles Waldheim argues for landscape urbanism as a uniquely suited medium. He associates the origins of the discipline’s thought to the postmodern criticism on modern architecture and planning, for being unable to address the decentralised urban form produced by industrialised modernity (2006, p. 37-39). Although the concept seems to react both to the compartmentation of modern science and the rigidity of urban (modern) models, the argument here is that the notion of landscape might also be used to describe and address pre-modern conditions such as the ones presented in the mining urban realm of Minas Gerais. This retrospective view with contemporary lenses allows the dismantling of modern constructions of this period embedded with notions of ‘disorder’, ‘irrational’, or ‘organic’.

Nineteenth-Century transformed landscape

As argued before, the eighteen-century gold mining in the region has produced a unique form of precocious urban network. However fragmented, and containing a certain level of administration hierarchy, it presented its particular kind of horizontality with high levels of exchange between diverse combinations of human settlements, mining and agricultural economies. Much resonance is found between these conditions and the ones used to describe the contemporary urban landscape, be it Secchi’s Cittá Diffusa (2012) or Waldheim’s ‘decentralized urbanisation’ (2006, p. 37).

Another interesting characteristic of mining economies that find resonance in the contemporary condition is its indeterminacy and constant change. When the superficial gold disappeared halfway through the eighteenth century, Minas Gerais’ economy was forced to diversify and expand in other sectors while mining continued to hold its share, a substantial asset of the state – and the country – until nowadays. With dramatic changes in the modus operandi of resource extraction, not only was the economy forced into resilience but also its landscape.

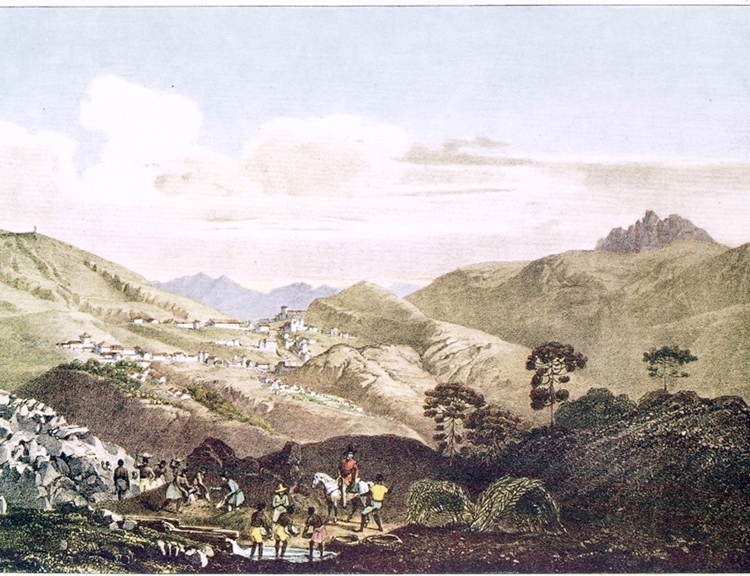

Fifty years of an intense gold rush all around the mining province has left behind a revolved ground with minimal remains of a ripped-out rainforest. The image seemed to have shocked the foreign visitors who travelled into the Brazilian hinterland in this period5, having left descriptions of abandonment and despair that contributed significantly to the idea of economic and social decay that for a long period overshadowed the historiography of nineteenth-century Minas Gerais6.

Traveling between 1817-1818, Saint-Hilaire found it extremely difficult to give a precise idea of this very irregular village of Villa Rica (Ouro Preto). He nevertheless attempts to describe it as been built over a long series of hills that border the Rio Ouro Preto, some advancing others retreating, some of them too steep to have houses on, with poor vegetation and large excavations. This irregular urban form, following gold rather than reason, was absent of any urban form or logic that would remind him of a European village.

3. View of Vila Rica by Rugendas. Circa 1835. In the foreground, slaves mining alluvial gold are pictured. Source: wiki commons

For the Briton Richard Burton, travelling 50 years later, the most impressive aspect of Villa Rica, which he considered a “straggling and overgrown mining village”, was the number of shapeless curves and narrow streets. For him too, the mining activity was still something remarkable in the panorama, “characterised by hills and reminding of the gold, because everything had been turned over and removed by the Mineiro”. (Burton, 1869, p. 78)

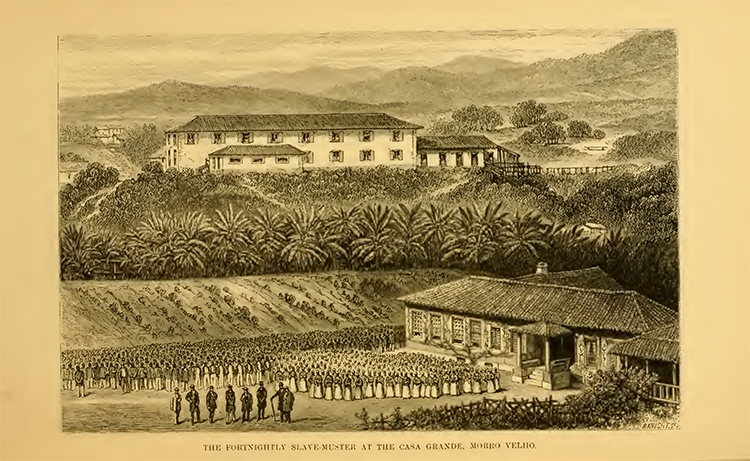

The descriptions of the village of Campos de Congonhas (today Nova Lima) are similar: “an irregular mixture of bulge and hollow, sprinkled with church and villa” (Burton, 1985, p. 193). When arriving at the town, his impressions show that the decay, many times depicted, was not a ubiquitous scene: “Congonhas [today Nova Lima] has been cured of the ‘decádence et abandon’ in which St. Hilaire found it forty-seven years ago. Built by mining, it fell with mining, and by mining, it has been “resurrected”. (p. 195)

The municipality of Nova Lima is exemplary of the turn around of the mining industry in the 1800s under the guiding hands of large (British) enterprises. It has, as described by Burton, been built by mining, fallen with mining and been resurrected with mining, indicating intrinsic connections between the city and the natural cycles of mining. Its urban history often blurs with the history of the mine named Morro Velho (Figure 4) and the company that owned it for the most prolonged period – since 1834 -, the (also British) Saint-John Del Rey Mining. The British presence along with its mining activity shaped the landscape of Nova Lima in many aspects, in the factual construction of its urban infrastructure and also culturally. The implementation of a private railway in 1913, connecting Nova Lima to the province capital and subsequently to the ports in Rio de Janeiro served primarily to facilitate product export – in the face of the previously poor condition of the national transport network – but also allowed the connection of Nova Lima dwellers with a more extensive urban network. This input of technology and modes of connection also meant that the urban network of mining became more efficient. The company was also responsible for the implementation of electricity and did extensive works towards water supply, canalising river waters mainly for the washing of gold, but also serving the city. Until today, the remains of the canals mark their presence in the city and are active elements of local identity and collective memory.

4. View from the Casa Grande at Mina Morro Velho. Source: Burton, 1869.

The new modes and scale of mining have therefore dramatically changed Nova Lima’s landscape, not only by digging its soil but also by complementing the town with modernised industrial infrastructure along with English cottage houses and gardens. Under the leadership of this particular mining company Nova Lima municipality has developed to become the most prominent mineral exporter in the state today.

The end of the nineteenth century was also marked by the emergence of Belo Horizonte, the state-built and planned capital, which, as Felipe Correa sees in “Beyond the City” (2016), is a particular urban model built as a direct by-product of resource extraction in Minas Gerais. While focusing on Belo Horizonte and its nineteenth-century grid, Correa overlooks what has proceeded the city’s creation. The lay-outing of such an organised and hygienic city was precisely meant to oppose the intricate network of small colonial towns carved into an undulated topography. Ouro Preto, the former state and earlier provincial capital, is usually presented as the counter image of Belo Horizonte in a portray that often highlight its problems and limitations to justify the need of a new ordered city in a modernising age.

However, as Moraes (2007) has cleverly seen, the urban landscape of Minas Gerais was not represented by Ouro Preto solely, but rather by an urban network of strategically distributed politics, power and functions, intertwined with mining and agriculture. It was constructed upon the dynamics and the necessities of the mining activities acting as generators of its territorial organisation, a spontaneous engineering shaped by real necessity. This constellation as such is replaced at the turn of the 19th century by the centralisation of power and functions with the foundation of a new capital under positivist influences but also by the centralisation of mining activity under the leadership of large foreign companies in control of extensive territories.

Twentieth-Century Modernisation

The nineteenth century was a period of intense transformation in Brazil and Minas Gerais, shifting from colony to Empire (1822) and later to Republic (1891) and also shifting from an economy of small-scale mining, agriculture and manufacturing towards underground infrastructured mining, modernised farming and later to industrialisation. The transfer of the capital (1895) meant a transfer of power from Ouro Preto aristocrats to cattle breeders and manufacturers from other regions. (Resende, 1974). The new republic and the new century meant, therefore, a new beginning to the province in which mining activities have continued to play a dominant role in shaping its economy and landscape.

Despite sharing the same birthmarks of many other mining towns such as Ouro Preto, Mariana, Itabirito, Sabará and others, there are many particularities in the process of evolution of Nova Lima that makes it an exceptional case among its sisters. When put together in perspective, the once strong urban constellation formed around gold extraction practice and economy has been dissolved. While a privileged group has been included in tourism routes for being hosts of memorable colonial art and architecture (Ouro Preto, Tiradentes and Congonhas mainly), the rest has been left in forgottenness. Amongst the last group some of them are still victims of the profound – and often silenced – transformation and degradation of their landscape and therefore collective memory.

Not hosting any colonial architecture worthy of attention, Nova Lima would have perfectly fit into the second group of towns, more specifically next to Mariana, Itabira and Itabirito. Its land rich in gold and iron ore continues to be explored up to today, without significant demographic or urban expansion – a condition that might be on the verge of change. However, a series of events and assets has placed Nova Lima in a different position, now under enormous urbanisation and environmental pressures.

The situation started turning in the first decades of the twentieth century when the scenario of mining began to change, and Nova Lima became more and more connected to the metropolitan network established with the new capital Belo Horizonte due to both the transportation network and the industrial exchange. The city of Belo Horizonte borders Nova Lima in the north, with only 30 kilometres separating both cores.

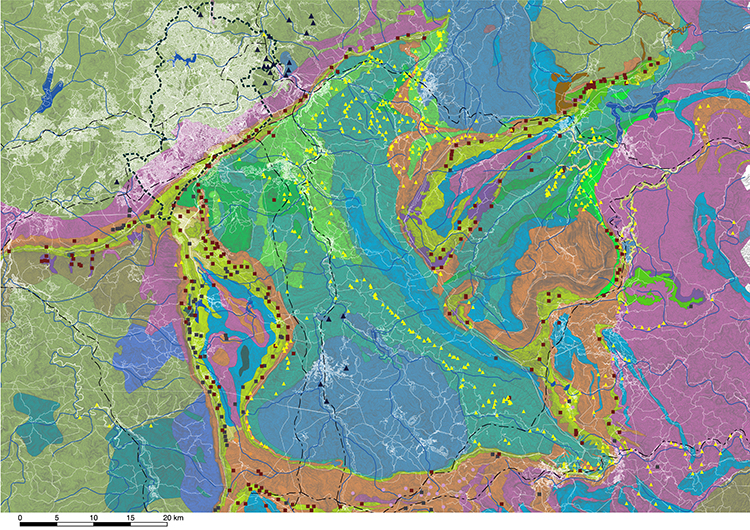

After standing for a long time on the sidelines of the national industrialisation scene, focusing mainly on mining and cattle breeding, Minas Gerais’ industry started to prosper after 1920 with the instalment of several steelwork plants. As part of a regional development project, and boosted by the attraction of investment in the recently inaugurated capital, the most appropriate place for steelwork plants was the region richest in iron, the Quadrilátero Ferrífero. When the plants began activity, Nova Lima was already privately connected to this network through the rail line constructed by Morro Velho. The growth of this industry paired with the progressive slowing-down of gold extraction meant that Nova Lima started gradually shifting towards iron ore extraction, today its primary activity.

5. The geology of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero. At the top-left, Belo Horizonte, at the cevntre, Nova Lima, at the bottom-right, Ouro Preto. Dots represent mineral resources. Source: The author, using GIS data of CRPM

The national-regional projects for development were intensified in the following decades, primarily applied through the binomial “Energy-Transport’”. For the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, the project had several (spatial) implications. The creation of a state-level energy company, CEMIG, in 1952, boosted the development of industry, especially in the western portion of the capital. The second half of the binomial, the transport, meant large investments in the road network7. A common phenomenon in urbanisation patterns is the development of urban settlements along paths and roads, as Panerai has explained (2006), and this would not be different in Nova Lima. Rather than the spontaneous and gradual process verified in the paths belonging to the network of mining towns since the eighteenth century, along these newly opened roads, the occupation has been fast, aggressive and highly induced, under the influence of large-scale mining and land property. Therefore, large-scale mining is a producer of large-scale urbanisation processes. As mining technology improves, the efficiency of extraction increases and this contributes to the acceleration of changes in the landscape and consequently accelerates the urbanisation processes. The 1950s were a period of significant change, also for Saint John Mining. It was a period of economic challenges, leading the company to sell properties along the newly opened road connecting Belo Horizonte to Rio de Janeiro, at the western edge of the municipality. However well located, the land was poor in minerals. (Pires, 2003). The scenario that triggered the transformation of Nova Lima’s pattern of urbanisation starts therefore to take shape: 1) a newly opened highway, connecting a previously inaccessible territory directly to Belo Horizonte; 2) a land poor in iron, therefore uninteresting to the mining sector, but now highly interesting for real estate becomes accessible; 3) economic crises in mining means a fall in gold prices and the opportunity is take up to convert unusable land into real estate capital.

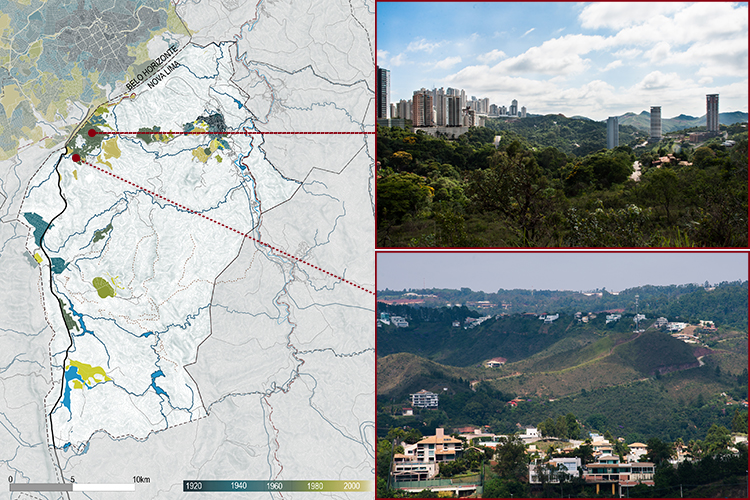

6. Left: Timeline of Nova Lima’s fragmented expansion (nucleus is to the right and Belo Horizonte to the upper-left. Right: Two forms of recent occupation: vertical and horizontal condominiums. Source: the author.

Until this moment, the retention of land in the hands of one sole owner had halted the urban expansion to the south (image 6). Historically, Belo Horizonte’s growth had been, so far, to the north and west directions due to a number of factors: 1) the fragmentation of (small-scale farming) land in those areas, when compared to the mining neighbours to the west and south, Sabará and Nova Lima, respectively; 2) the governmental projects developed in those directions, namely Pampulha and the Cidade Industrial; 3) the natural barrier imposed by the Serra do Curral ridge, running on its south-east border, separating Nova Lima.

Changes in the dynamics of Belo Horizonte’s real estate market and the ups and downs of the mining activities would therefore jointly contribute to the new forms of urbanisation in Nova Lima, beginning in the 1950s along the newly opened roads as alternative living close to nature. This movement intensified from the 1970s to the 1980s in the form of patched enclaved condominiums, when the city abandoned the compact model towards a dispersed urbanisation. From this moment a new mode of occupation, radically new for Nova Lima, started to mushroom at the borders of Belo Horizonte, in the form of high-income vertical condominiums, as a spillover of Belo Horizonte’s vertical expansion.

Belo Horizonte’s real estate market has, therefore, had immediate results in its metropolitan neighbour Nova Lima, which gradually started replacing inoperable mining land with real estate assets. Despite the dimensions of resource extraction in this area, Nova Lima still had – and relatively still has – a significant portion of its territory preserved as green areas presenting an exuberant landscape presented as seemingly endless succession of green hills. “Nature” had become the main marketing tool for real estate and the main motivation for dwellers of the new condominiums who wish to live in a sort of urban setting with all commodities provided, surrounded, however, by nature. Contradictorily, residential towers punctuate this exuberant landscape more and more, appearing entirely out of scale and place (image 7).

These new forms of urbanisation have been presenting new challenges to the usual clash between environment and mining – a third force acting simultaneously as land consumers and ecology activists. This double role of new dwellers is due to their frustrations over the broken promises of a “permanent view” used for marketing of new apartments. As the urban frontiers continue to expand, the window-framed green carpet of hills is replaced by a grey amalgam of high-rise condominiums. However new allotments always take advantage of the “last frontier” idea, the tendency is that urbanisation continues to expand south. The dependency of Nova Lima on mining and the fluctuations of its market in the past years has led the municipality to act strategically to attract a high-income population with its tertiary sector, changing its landscape dramatically.

7. Overview of the border between Belo Horizonte and Nova Lima. (The author, 2017)

Conclusions

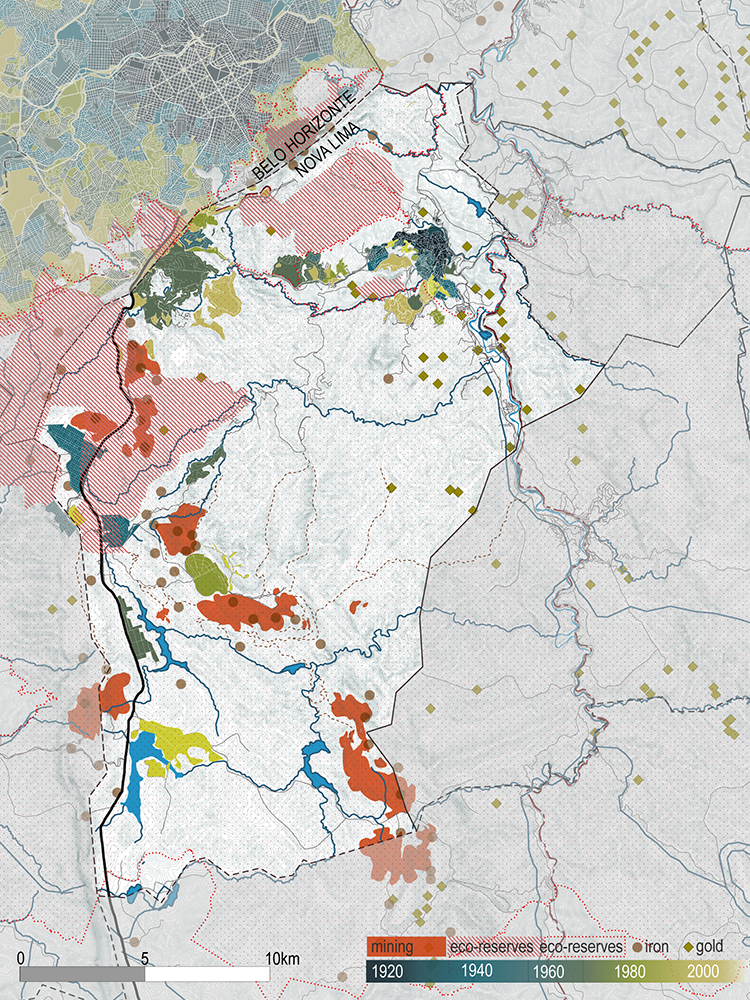

Throughout the centuries, the cyclic economy and itinerancy of mining activity have generated simultaneous cycles of fast urbanisation with the establishment of the eighteenth-century urban network, short decay with the re-organisation of economy and landscape towards diversification and accompanying accommodation of urban settlements to the new realities. From the second half of the nineteenth century, the recovery of Minas Gerais economy, mainly due to the resurgence of mining as a consequence of the improved technology, has also set the pace for a new era of territorial organisation, now concentrated around the new Capital Belo Horizonte. Today, as large-scale mining continues to advance in Nova Lima, large-scale urban expansion can also be seen in the same territory, made possible and directly influenced by the large-scale property structure of the former mining territory. The opening of new allotments is orchestrated by the opening of pits, since, after mining closures, they are filled with water and reconverted into a pleasant lake with added real estate value. The closing of mines has resulted in artificial reforestation that, after only a few years of fast Eucalyptus growth are again perceived as ‘nature’, also adding value to real estate capital, which has now become the third cycle economy of mining companies.

Seen through the lenses of landscape, the study of the spatial history of mining in Minas Gerais, and most specifically of Nova Lima, allows relations to be drawn between resource extraction and urbanisation, provdies an understanding of how they are both actors in profound transformations of landscape. They are both consumers of land and natural resources acting in contradicting roles of competition and mutuality. The concept has also allowed for the highlighting of the transitory dimension of the territory, being transformed over three centuries from nature to mining, from mining to town or from mining to “nature”, always profoundly imbricated in a social process of appropriation and subjectification.

The concept of landscape has therefore proven to be particularly useful in the context of resource extraction urbanism, as it is able to embrace this ambiguous landscape of mining, lying in-between the inflexible categories of urban and rural. While mining might be associated with industry and therefore intrinsically a modern urban setting, mine pits are predominantly located in settings traditionally considered as non-urban, as they relate directly to the natural resources, although they are globally connected to cities. Just like cities, mines are also potent agents in the transformation of landscape.

The historical perspective allowed one to perceive the ever-changing character of this territory, contributing to the (time) elastic notions of landscape, which focuses on processes rather than static images. Acknowledging that mining is cyclic and that urbanisation and mining are an entangled processes, we are left to imagine how then could cities be cyclic and therefore constitute resilient landscapes.

8. Overlapping of urbanisation, mining and several layers of environmental protection. Source: the author.

Notes

1. IBGE, 2010 census.

2. Although other sources diverge.

3. Curiously, recent research also revealed the existence of the “Mixed Farm” combining simultaneously gold mining and agriculture, sharing the same slaves (Paula, 2000, p. 63).

4. Despite land possession not being formally allowed before the Lei de Terras (Land Law) of 1850, concessions and allowances were distributed for those wishing to explore it, configuring something almost like a property with full rights of use. These concessions were also often commercialised. Urbanised areas naturally belonged to the Crown, with permits for inhabiting.

5. As the Monarchy was transferred and Brazil became the seat of the Portuguese empire and with its golden era coming to an end, the colony saw the large influx of foreign travellers, who started to traverse the territory, from the coast to the mining hinterland leaving many travel logs and paintings.

6. According to Paula (2006) this historiography has been revised in the last decades revealing instead a very dynamic and diverse economy in this period.

7. Construction on both BR040 – federal highway connecting Belo Horizonte to the then capital Rio de Janeiro – and MG 030 – state road connecting Belo Horizonte to Nova Lima began in the 1950s.

References

– Burton, R.O.P.-1869, (1983). Viagens aos planaltos do Brasil: Minas e os mineiros. Companhia editora nacional.

– Corner, J., (1999). The Agency of Mapping. In: D. Cosgrove, ed. Mappings. London: Reaktion Books, 213–252.

– Correa, F., (2016). Beyond the City: Resource Extraction Urbanism in South America. University of Texas Press.

– Cosgrove, D., (1985). Prospect, perspective and the evolution of the landscape idea. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45–62.

– Foucault, M. (1986). Of Other Spaces, trans. Jay Miscowiec, Diacritics 16. (original lecture in 1967)

– Holanda, S. B. D. (1936). Raízes do Brasil, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras.

– Resende, M. E. L. de (1974) ‘Uma interpretação sobre a Fundação de Belo Horizonte’, in Anais do VII Simpósio Nacional dos Professores Universitários de História. São Paulo.

– Lefebvre, H. (1999). A Revolução Urbana, Belo Horizonte, Ed. UFMG.

– Moraes, F. B. D. (2006). A rede urbana das Minas coloniais: na urdidura do tempo e do espaço.

– Moraes, F. B. D. (2007). De arraiais, vilas e caminhos: a rede urbana das Minas coloniais. In: Resende, M. E. L. D. R. & Villalta, L. C. O. S. (eds.) História de Minas Gerais: as Minas Setecentistas.

– Panerai, P. (2006). Análise urbana, Editora UnB.

– Paula, J. A. D. (2000). Raízes da modernidade em Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Autêntica Editora.

– Pires, C. T. P. (2003). Evolução do processo de ocupação urbana do município de Nova Lima: um enfoque sobre a estrutura fundiária e a produção de loteamentos.

– Plambel, B. H. (1979). O processo de desenvolvimento de Belo Horizonte: 1897-1970 Belo Horizonte.

– Saint-Hilaire, A. D. (1830). Voyage dans les provinces de Rio de Janeiro et de Minas Geraes.

– Santos, M. (2002). A natureza do espaço: técnica e tempo, razão e emoção, Edusp.

– Waldheim, C., (2006). The landscape urbanism reader. Princeton Architectural Press

Patrícia Capanema Alvares Fernandes has obtained her diploma as an Architect and Urbanist at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil in 2007. Between 2010-2012 she has conducted research at the Berlage Institute, Rotterdam, where she followed the program of Advanced Masters in Architecture successfully concluding it in June 2012. In this program, she has worked on the Kampungs of Jakarta, the infrastructure network of São Paulo, as well as the common spaces of refugee camps in Palestine, including extensive fieldwork for all the research. The last years’ experiences include research on Urbanisation and Development in the global south, for which a grant was received, and also teaching at a UniBH and UFMG, in Brazil. She is now pursuing a PhD at the KU Leuven investigating spaces of insurgency and modernism in Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Volume 1, no. 4 Winter 2017/18