Mapping Democracy: A Tale of Two Capitals

Anavil Ahluwalia

Capital cities have been the seat of political power and a central stage for their state’s political conflicts and rituals throughout the ages1. The Indian capital bears the markings of some of the most powerful empires. Once the seat of the British Raj, how has the city been appropriated post-independence? India declared herself as a democratic nation at the stroke of the midnight hour in 1947 and promised Equality, Freedom and Justice to all her citizens2. However, does the capital city reflect these ideologies? How will the central government’s ambitious project – Central Vista Redevelopment 2019, widely condemned across the country, shape the city? The research attempts to answer these questions through an analysis of administrative centres – symbolic of sovereignty and democracy – in New Delhi and Washington DC. The paper intends to ground the study through a series of comparative mappings of the Central Vista (New Delhi) and the National Mall (Washington DC) based on three parameters: Morphology, Accessibility and Public Open Space usage. The paper aims to spatialize democracy and its characteristics in modern cities and highlights the consequences of the redevelopment project proposed. The findings reveal government-induced spatial injustice prevalent in the former world’s largest democracy and endorse the urgent need to re-examine what democracy stands for and its representation in cities.

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries witnessed the rise and fall of several political institutions (monarchy, communism, fascism etc.) with a major surge in the acceptance and establishment of democratic forms of governance. Samuel Huntington, in his 1991 book ‘The Third Wave’ attempts to explain the ‘waves’ of democratisation. He identifies three waves of democracy and two ‘reverse waves’; the first ‘long’ wave began in the 1820s (with the widening of the suffrage) followed by a reverse wave (due to Mussolini’s rise), the second wave in the 1920s (triumph of the Allied Forces in World War II) followed by another reverse wave and the third wave in 1974 (began with the Carnation Revolution in Portugal)3. However, at the time of publication, the observed signs of the commencement of a third ‘reverse’ wave. In the last decade, many observers such as V-dem, Freedom House, Civicus, The Economist and IDEA have suggested a decline in democracy. The third wave of autocratization has accelerated considerably as the level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen in 2020 is down to levels last found around 19904.

Different political orders brought with them a unique planning style and spatial configuration. Space is a crucial political issue, Henri Lefebvre argued, as it is the ultimate locus and medium of struggle: “There is a politics of space because space is political”5. The urban reflects the will of the sovereign. V-dem in its 2021 report claims that India, the world’s largest democracy, has turned into an ‘electoral autocracy’6. India’s decline over the last ten years has been described as “one of the most dramatic shifts among all countries in the world”7. The paper explores democracy in crisis and the unfolding of the political spectacle through an analysis of the alterations and reconfiguration of the Indian Capital.

Entrance of India Gate, 2019. Source: Author

The Making of New Delhi

India awoke to life and freedom at the stroke of the midnight hour on 14th August 1947. The country liberated from the British Empire and declared herself as a sovereign, secular, democratic republic. The largest democratic state in the world chose Delhi as her capital. Owing to its central location on the Indian subcontinent, it has been the seat of power since the twelfth century. The city as we know it now constitutes seven cities: “It can be argued that what all the past seven cities of Delhis shared in common was the ‘aura’ of being a capital city and for centuries this characteristic persisted”9. The last of these, Lutyens Delhi, designed to be the capital of the British Empire was essentially an expression of power and means to assert their dominance. Inspired by the likes of Washington and Paris, Lutyens and Baker designed the city on the Garden city concept. In his ideological aspiration for the new capital, Baker wrote to Lutyens, “It must not be Indian nor English, nor Roman, but it must be Imperial”10. Axiality, symmetry and size were the primary characteristics through which the British Crown represented its imperial claim, its sense of justice, and superiority. Architecture and urbanism became spatial dimensions of exercises of power11.

1947 was a turning point in the history of Delhi – Independent India had undergone partition and the choice of capital was a pressing matter. Gandhi, the father of the nation, was of the view that the leaders set an example of simplicity and the Viceroy’s house used as a hospital. However, Mr Nehru, the first prime minister of the nation, believed a planned city such as New Delhi, would project a desirable image on the international stage. Democratic India inherited a colonial capital. Post-independence access to Lutyens Delhi was empowerment. The ‘democratisation’ of the imperial city is perhaps the most visible in the vast expanse of land on Rajpath, around India Gate12. The appropriation and usage of the grand avenue prompted the celebrated historian Narayani Gupta to write “An Indian Champs-Élysées came to life in a way very different from what Lutyens intended”13. The inauguration of the Amar Jawan Jyoti and the proximity to Children’s Park transformed India Gate – “a British attempt to recreate the grand Mughal court in Delhi”14 – to a beloved Public plaza of the city. Many princely palaces built around the C-Hexagon were converted to house public functions such as museums, art galleries, the National School of Drama and courts. In the last decade or so, it’s been observed that many Muslims from the Old Delhi area flock to the gardens for late evening picnics in the summer15. The lawns, popular with tourists and locals alike, are symbolic of the breaking of socio-economic shackles and demographic boundaries. With protests at Boat Club, late-night ice creams at India Gate and post-lunch strolls at the Rajpath Lawns, the citizens made the city their own.

Democratization of Kingsway: The public enjoying a fair on the Rajpath Lawns, against the backdrop of Rashtrapati Bhawan on a late, winter afternoon, 2020. Source: Author

The unMaking of New Delhi

Delhi saw over 12,500 protests in 2019; the highest in eight years16. The year ended on a stormy note with several protests and rallies organised against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the National Register of Citizens (NRC), and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) violence. Amidst the chaos, the central government announced the Central Vista Redevelopment Project. “More than mere homes for government leaders, they [government buildings] serve as symbols of the state. We can, therefore, learn much about a political regime by observing closely what it builds”17. The Modi Government has proposed to redevelop the heart of the country: New Delhi. “How cities are planned, designed and built reflects ideas and ideologies concerned with organisation and structure, control & order, and power”18. The development projects undertaken by the government in the last few years aim to control, commodify and commercialise public space such that everyday uses are no longer possible.

The construction of the War Memorial at India Gate is a fine example. It ensued the fencing of the parks in 2018 and has rendered three lively public parks into landscaped gardens, devoid of the public. The entry and exit gates along with guarded security checks instill a certain hesitation, psychologically: the very fact that gates exist suggests that somebody is allowed and somebody isn’t. The brunt of such developments almost always falls upon the less privileged. It is important to note that Lutyens Delhi is home to the most powerful and rich Indian bureaucrats, politicians, ex-pats and entrepreneurs. Thus, the presence of accessible public space amidst an elitist enclave was symbolic of a step towards ‘democratization’ of the city. In addition, the fencing robs the visitor of the many charms that one might have experienced otherwise; to buy balloons, chaat and toys from vendors no longer allowed within the bounds; to cross paths with pedestrians and cyclists cutting across the gardens or resting momentarily in its shade in hot summers. The lawns that were part of a variety of activities and happenstances in the city have been reduced to a ‘destination’. The fencing has drastically reduced its usage and resulted in controlled accessibility and limited everyday use.

Edward Said states, “Just as none of us are beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings”19. “These ideas expose the spatial causality of justice and injustice as well as the justice and injustice that are embedded in spatiality”20. The redevelopment requires a change in land use of seven pockets (101.1 acres) from public/semi-public to government offices. This will monopolise the heart of the city and encourage consumerist culture. The proposal that involves the addition of ten secretariat buildings along with the residence of the prime minister, at the cost of existing public functions along the avenue magnifies state control and enhances spatial injustice.

The unMaking of New Delhi: A family rests under the shade outside the bounds of War Memorial on a warm sunny evening, enjoying ice cream while gazing at India Gate, 2021. Source: Author

Mapping Democracy – A Comparative Analysis

Edelman said, “We must not forget that politics is a spectacle and that the ‘spectacular’ requires a stage on which to be performed”21. The capitals are spaces where the ‘political spectacle’ is manifested in all its glory – they are the symbol of the nation-state and representative of its beliefs. “A capital is the space that symbolically integrates the social, ethnic, religious, or political diversity of a country…Through its architecture and urban design, it provides constructed spaces which serve as instruments and offer a language of representation for the entire nation”22. They are the symbolic and formal centres of their nations’ respective public spheres and therefore, two capitals have been chosen for the research23.

Democracy must guarantee Spatial Justice. This involves fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to use them24. The system of governance prioritises people, thus, democratic spaces must be truly public. “The most effective democratic space must be accessible, flexible, welcoming and safe. It has soft boundaries and is easy to navigate. It provides the opportunity for people to shape spaces themselves”25. The functions, accessibility and allowed activities and behaviours are all indicative of how ‘democratic’ and public space is.

A city designed to reflect these ideals is Washington DC – widely referred to as ‘The Political Capital of the World’. Post the American Revolution of 1775, the country emancipated from the British Empire. Pierre Charles L’ Enfant’s 1791 scheme accentuated the gridded plan with diagonals highlighting key civic buildings while the McMillan plan in 1902 emphasised the open, public greens of the Mall to facilitate interaction between citizens and the government “symbolising a democratic society”26. “The Mall tells the story of America” said Benton-Short, “It’s where we celebrate, protest and play. It’s the most important public space in American civic life”27. However, she also acknowledges the increasing fortification of American cities post 9/11. She argues that the Mall symbolises freedom and democracy but surrounding it with barriers, cameras and chain-link fences contrasts with its symbolic role in society28. In the words of Vale, cities “are being secured from the public, rather than for it”29. The militarisation of spaces and urban form at the cost of an active public life falls short of our aspirations for a just and democratic city.

New Delhi and Washington DC were both designed with unique political ideologies. They are symbolic and representative of what the nation stands for and often sets precedence for other towns and cities in the country. Over the years, both cities have observed various modifications and are comparable in size and formal design. The geometry of their plans, clearly visible on maps, shows a large central axis, a perpendicular axis and diagonal avenues ending at roundabouts. They are the seat of government; The Central Vista (1.8 miles or 3 km in length) and The National Mall (2 miles or 3.2 km in length). The research is focused on these urban spaces of power. A framework of spatial characteristics that reflect and mirror the democratic ideals has been chosen – a framework to ‘map’ democracy. The three parameters that allow for a holistic analysis are; Morphology, Accessibility and Public Open Space. The mappings are limited to a distance of 500 metres from the core avenues.

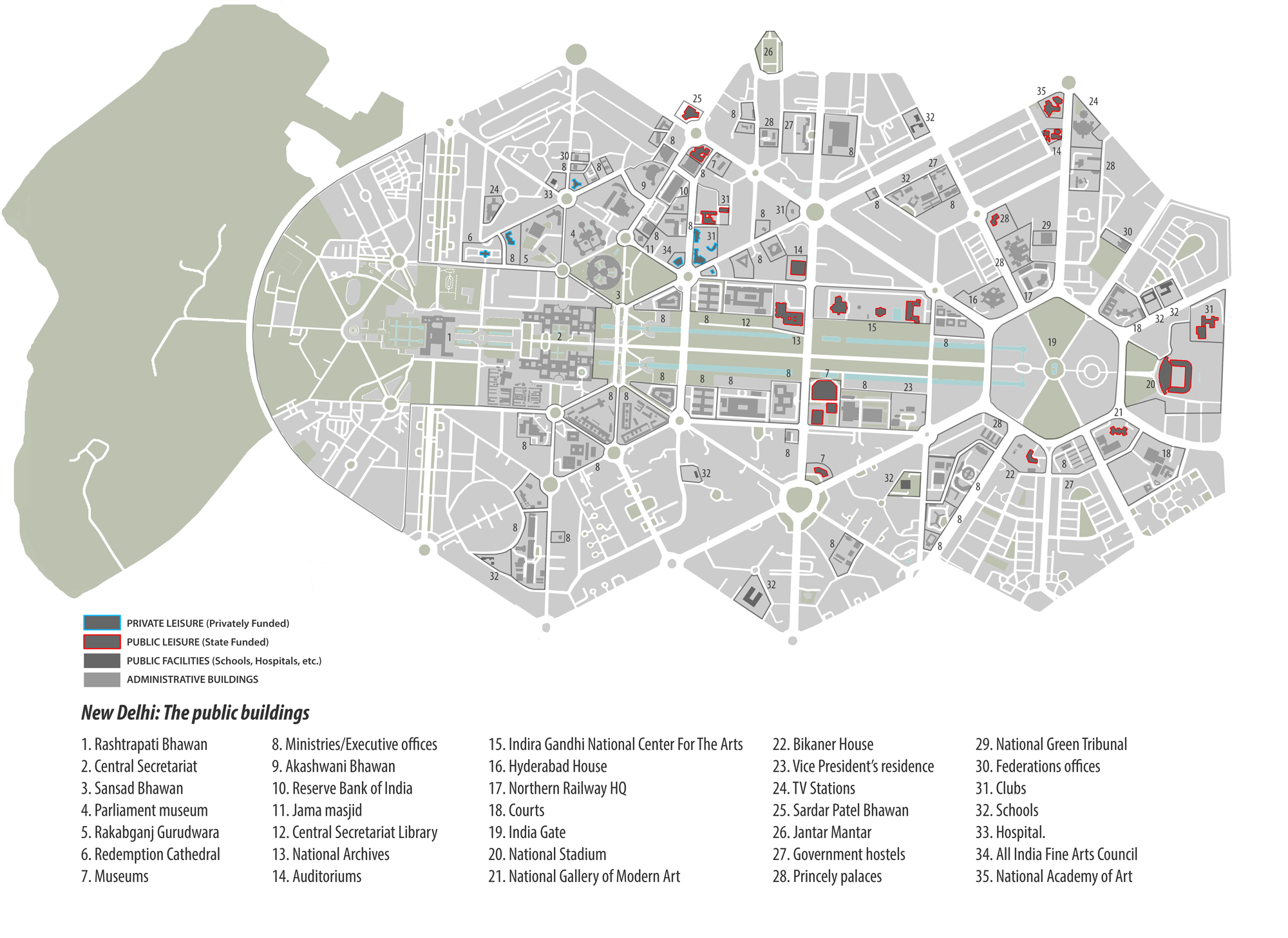

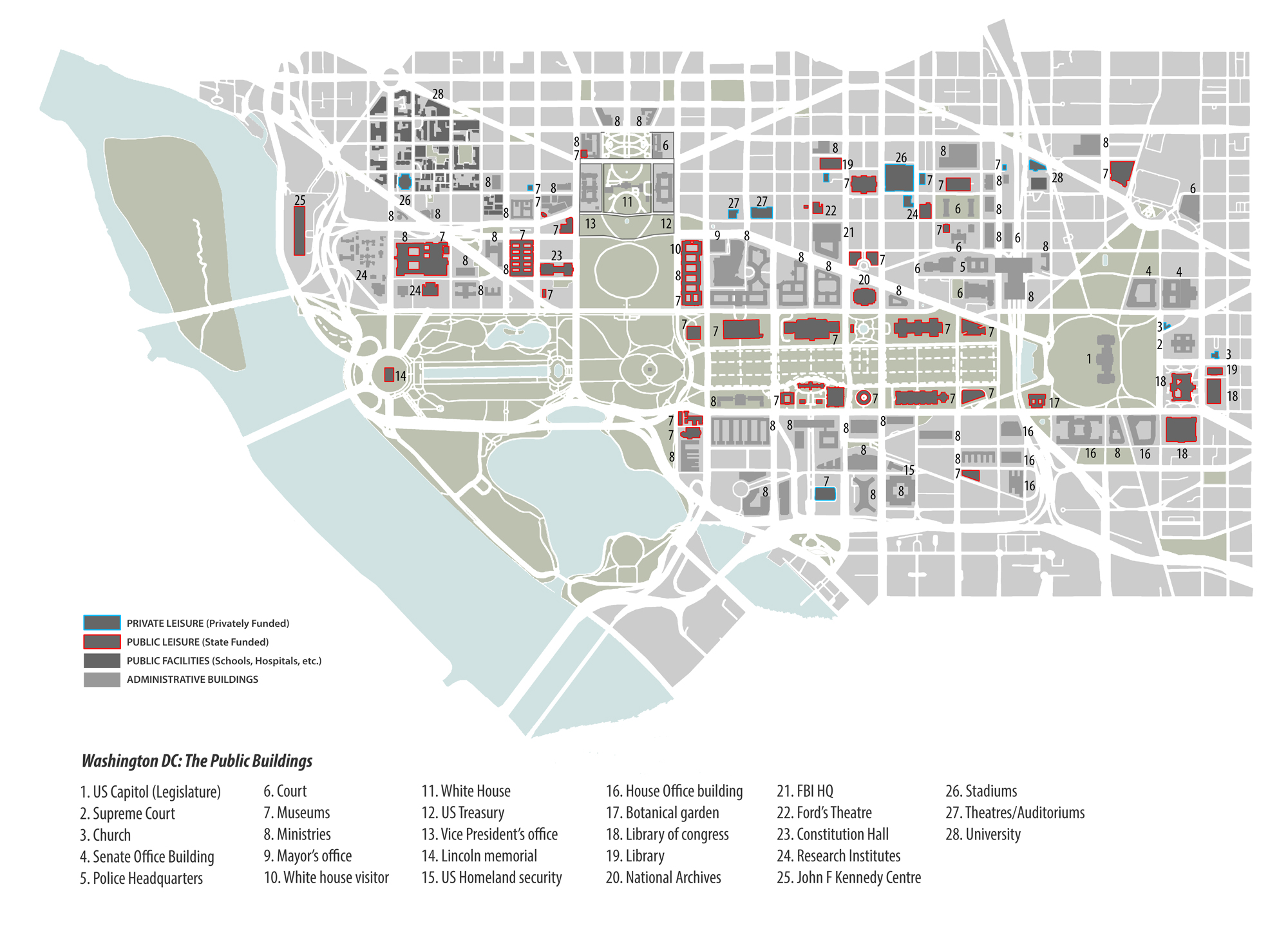

1. Morphology and The Public Buildings

This set of mapping provides a simple understanding of the volume and spread of Public buildings and institutions in proximity to urban spaces of power. Public Buildings refer to all government buildings as well as buildings that house public facilities or leisure. The distinction between state-funded and privately funded leisure buildings is a measure of each government’s intent with one of the most powerful spaces in their respective countries. Infiltration of public buildings in and around an administrative core can create a certain balance; it sends a message that space belongs to the citizens as much as it does to the government. However, their mere existence will not suffice. How they sit and interact with, and within, the landscape of power is crucial. This brings us to another aspect the maps bring to light: the morphology of the built and its relationship to the open space. The Built on Edge (B.O.E.) typology in Washington DC is in sharp contrast to the Object in Space (O.I.S.) typology (conforming to the Garden City concept) in Lutyens Delhi. The setbacks in O.I.S. typology segregate the private and the public realm. Lutyens’ original plans included hedges at the edge of the plots, which, post the 1984 Delhi riots and 2001 Parliament attack, gradually gave way to solid boundary walls. “Accessibility and the ability to touch is powerfully democratising. It is commonly understood amongst experts that urban design guides urban culture. If buildings, especially government buildings, are imposing, far away from the street or hidden behind walls, it propagates a culture of people seeing their government as imposing, distant, far from them and even hidden”30. The Public Buildings on the Vista function as three separate units within their bounds while the government buildings obscure behind leafy canopies, fenced walls and numerous security checks. It has transformed the relationship between the street, the building and the user. What is lost is the everyday experience and social encounters of the urban society.

Morphologically, the B.O.E. typology and the absence of boundary walls in Washington allow for greater interaction between the built and the user, thus adding to life on the streets. However, 9/11 has resulted in the paranoia of securitisation. The temptation to construct ‘securescape’ push toward street closures, enhanced setbacks, high boundary walls and strict design guidelines. Graham in his analysis of the ‘US Homeland’ post 9/11 states that a massive process of ‘re-bordering’ is underway: “This has involved a reimagination of the nature of US civil society as a bounded, national space whose flows and connections elsewhere—of people, information, commodities, and money—can be demarcated, surveilled, and carefully filtered”31. Eventually, the urban life may become “attenuated by the pauses at building perimeters, and more and more places may become places of secured sanctuary, detached and edited from the flows of open accessibility”32.

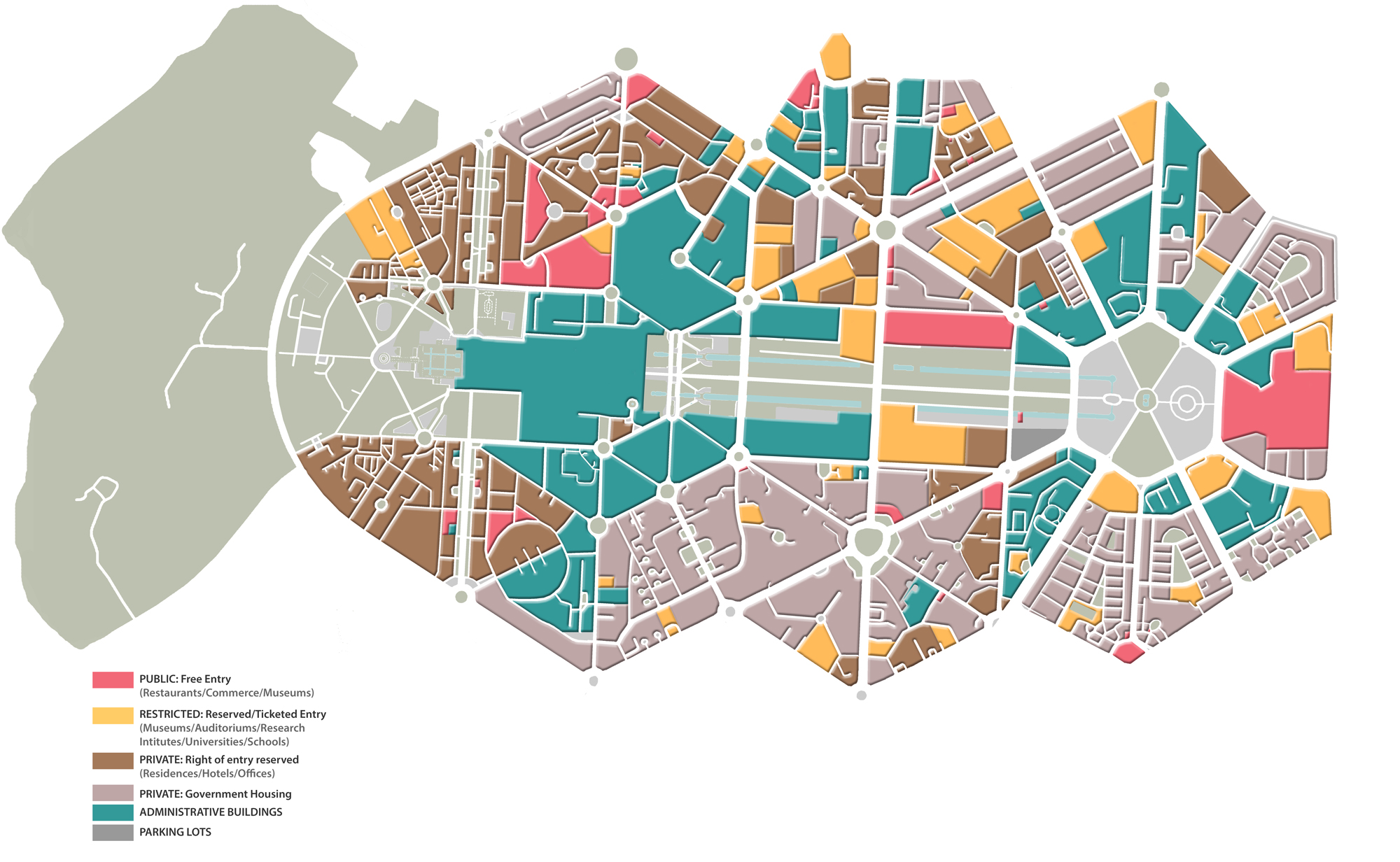

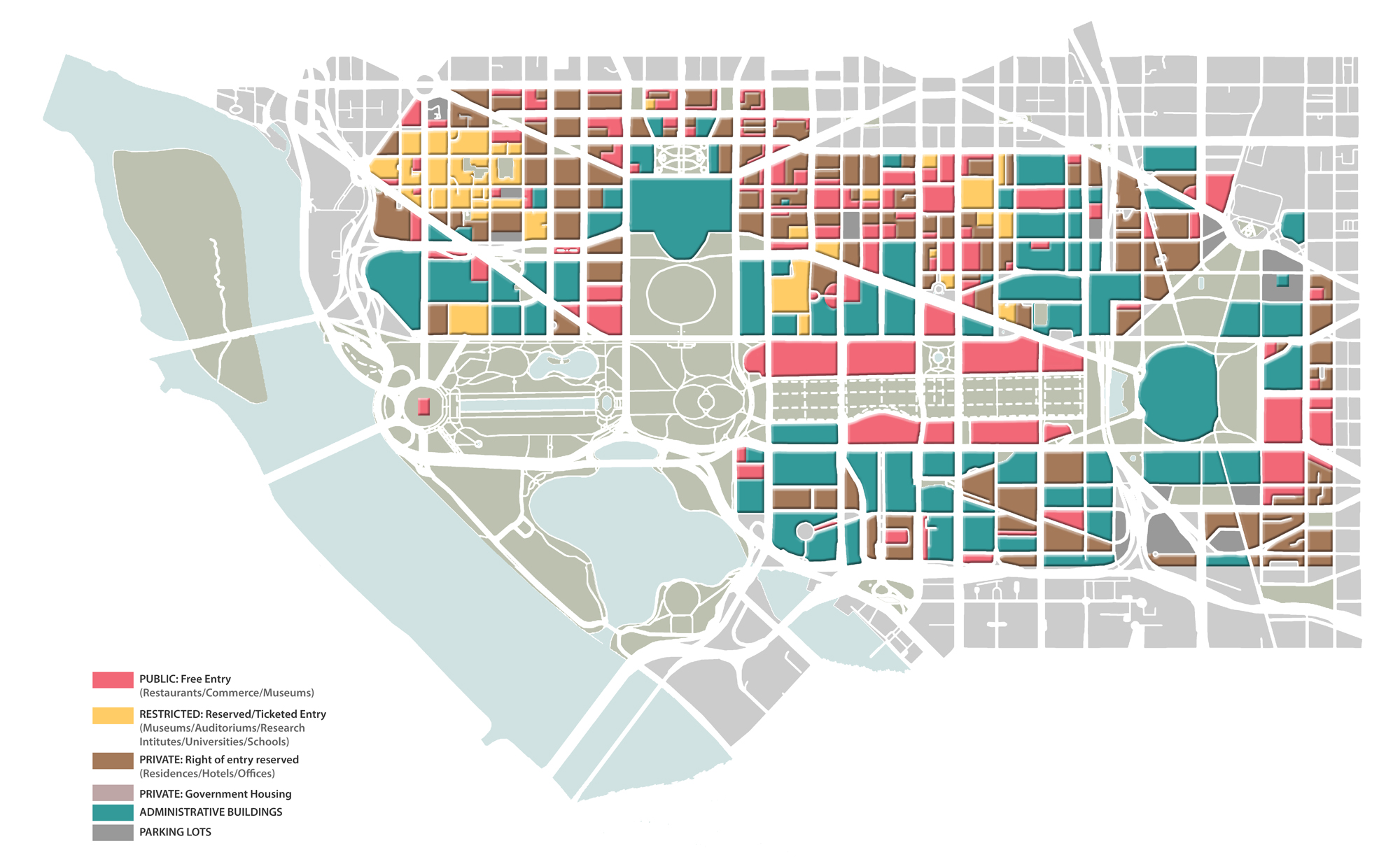

2. Accessibility

The mappings indicate the degree of accessibility of plots by considering Ground Floor-functions only. The beauty of the Mall is that a plethora of free-entry state-funded museums surround it. The diverse built functions in and around invite a variety of user-groups to experience the precinct. The design of the ‘People’s House’ is meant to make it easy for the public to meet and petition their representatives, and is the most accessible building for reporters33. However, enhanced security has impeded access; ending candlelight tours of the White House, and closing the West Steps of the Capitol which once delighted the eye with a magnificent panoramic view of the Mall. In the days leading up to the presidential inauguration post the attempted coup, twenty-five thousand troops poured into the capital. With the Mall closed to the public and the Capitol blocked by barricades, the city appeared guarded and distinct: “It looks like a military staging area because that’s exactly what it is”34. The challenge of securitisation, reshaping the public realm and questioning who has access to it, has long penetrated the planning sphere and urges a thoughtful public debate.

Lutyens Delhi, on the other hand, grapples with an overwhelming presence of government offices and housing as a result of stringent land regulations and a strong interventionist role of the state. The 1988 LBZ (Lutyens Bungalow Zone) Guidelines, in force till date, are responsible for the zoning and segregation of land use that refrains from encouraging mixed-use development. The city is “a sheltered enclave for the administrative elite”, as the Vista is surrounded by government bungalows allotted to politicians and bureaucrats35. Despite being largely state-owned, the city remains aloof and distant to the average Indian, offering limited public functions and opportunities for engagement. The Building Bye-laws focus on individual plot conditions that further compromise the publicness and character of the city.

With the President’s estate, Rashtrapati Bhawan, at one end and the India Gate at the other, the Vista could have been symbolic of the balance between the state and its citizens. However, the existing public functions shall give way to additional government offices due to the redevelopment proposal, decimating the public quality of the precinct. The India Gate and its bounded greens would be the only public space left for the citizen at the Vista. Thus, what could have been a balance has become, in essence, an alienation.

3. Use of Public Open Space

Public Open Space is defined as an open piece of land, both green space or hard space, to which there is public access. Public spaces within an immediate radius of 300m have been considered. Lefebvre notes, “it is the everyday that carries the greatest weight. While Power occupies the space which it generates, the everyday is the very soil on which the great architectures of politics and society rise up”36. The public realm is where the ‘everyday’ plays out. With several outdoor activities that include sports, farmers’ markets, plazas, amphitheatres and gardens, the robust use of open spaces creates a lively atmosphere at the Mall. The appropriation of the Vista post-independence and recent developments diluting the public quality of the precinct have been discussed previously. In addition, the greens of New Delhi are a part of the bungalows and thus are private, bounded and segregated from the public realm. Animated edges and integrated greens are design decisions that could enhance the urban quality of life.

It is important to acknowledge that, along with social and cultural stages, they are also important political sites. Public space is a facilitator of agency and fosters democracy: “It is key in setting the stage for people to join in with civic life, with politics, the democratic process and democracy in its broadest possible sense”37. John Parkinson states that the proximity to decision-makers matters so that “citizens can cloak their claims in symbols of national importance, associating their claims with the self-same dignity that elected representatives draw on when making their claims and decisions”38. The Vista and the Mall have historically been important ‘stages for democracy’. The 1988 Farmer’s protest at the Boat club successfully secured a waiver of power and water bills, and a higher price for sugarcane; The Great March on Washington resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. For the demos to make their claims and practice active citizenship, the availability and access to public space in proximity to urban spaces of power are pivotal. These spaces are under two major threats today; Policing and Privatization.

At the Jefferson Memorial, “the unsightly hodge-podge of jersey barriers, planters, snow fencing and flimsy barricades were so confusing that the Park Service installed a sign to clarify that the Memorial was, in fact, open to visitors—underscoring how intimidating it has become 39. In the 1960s, one could go right up to the Rashtrapati Bhawan, to voice one’s opinion or for an evening bike ride. Subsequent to protests turning violent and terror attacks, the state has conveniently chosen to ‘designate’ spaces farther away while the corridors of power have become ‘elite securescapes’. Peter Marcuse, however, argues that the Right to the City has long been under siege, and the false use of the threat of terrorism is only an accentuation of already existing trends, used to restrict democracy in cities and across the nation40. Monitoring and surveillance of the public realm may “threaten the role of the city as an active and unpredictable social space of encounter”41.

Reflections

“Freedom and power bring responsibility. The responsibility rests upon this Assembly, a sovereign body representing the sovereign people of India… A new star rises, the star of freedom in the east, a new hope comes into being, a vision long cherished materialises. May the star never set and that hope never be betrayed! We are citizens of a great country…All of us, to whatever religion we may belong, are equally the children of India with equal rights, privileges and obligations”42.

In 1937, Nehru said “the Constituent assembly that we demand will come into being only as the expression of the will and the strength of the Indian people…It will represent the sovereignty of the Indian people and will meet as the arbiter of our destiny”43. Seventy years on, the constitutional vision and the political reality of India have frontally collided, and the Indian capital is its witness44. New Delhi is the psychological centre of the country and the seat of the central government. The space, symbolic of the Indian democratic state, must prioritise people in its spatial planning. Edward Soja warns that the political organisation of space is a particularly powerful source of spatial injustice45. The Central Vista Redevelopment demonstrates this very well. The recent and proposed developments in the ‘Formal’ public sphere are increasingly and systematically excluding people as citizens, purposive publics, and privileging incidental or leisure publics46. The design purposefully alienates the state and its citizens rather than creating opportunities for them to co-exist and share the same space. That the developments and proposals are State-led is a major concern for it is with the state the responsibility lies to create a healthy and equitable city and retain the spirit of democracy. However, despite backlash from the design community across the country and countless petitions, the state’s decision to go ahead with this expensive and expansive project amidst the pandemic certainly raises questions. The city, a long way still from unshackling its deep colonial past, now confronts a (non)democratic phantasm head-on. It is our reactions that are critical towards developments as well as the autocracy masquerading as democracy. It is of utmost importance for the citizens to be aware and rise against the wave of autocratization engulfing the country.

Lefebvre, crucial in the political instrumentalization of space, argued that it is both a political product and a political stake: “Space is political and ideological”47. “He viewed social and public space as significant not only to healthy and humane cities but to a truly democratic and inclusive urban society”48. When public buildings and spaces are contained and restricted, they result in a diminished civic life and affect daily experiences of urban life. High-security zones manifest themselves as fragmented, militarized and exclusive spaces. Video monitoring of public spaces actively suppresses dissent. Highly sensitive spaces such as the Vista and the Mall may be more vulnerable to threats, but the duty rests upon designers to strike a balance between perceived threats and risks of constrained public life. The urban must not be reduced to a tool for political representation and outward appearance but ensure it practices what the built manifestation stands for. The ‘co-existence of state and everyday life’ is a must in a Democracy. Accessibility is inceptive of communication and encourages the synchronization of claim-makers and decision-makers. A healthy and disciplined civic society may be utopian but we must constantly endeavour to achieve it. Democracy can and must be designed. Certain spatial characteristics can intensify or suppress the democratic quality of space directly affecting urban life. The paper does not claim that design alone can balance the relationship between the state and its citizens. However, design can contribute, enable engagements and facilitate participation. Design can manifest democracy in our cities, and thus, into our lives.

Notes

1. Minkenberg, M. (2014). Power And Architecture. New York: Berghahn Books.

2. Nehru, J. (1945, August 14). Inaugural Speech [Speech audio recording]<.em>. All India Radio https://soundcloud.com/allindiaradionews/pt-jawaharlal-nehrus-tryst-with-destiny-speech.

3. Huntington, S. (1991). The third wave. Norman, Okl.: University of Oklahoma Press.

4. Rashid, A. (2021). The third wave of autocratisation and why it was waiting to happen. [online] The Indian Express. Available at: https://indianexpress.com/article/research/the-third-wave-of-autocratisation-and-why-it-was-waiting-to-happen-7281739/” rel=”noopener

5. Lefebvre, H. (2000). Espace et politique. Paris: Anthropos., p. 59.

6. Alizada N., et al. (2021). Autocratization Turns Viral. Democracy Report 2021. University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute. Available at:

https://www.v-dem.net/en/publications/democracy-reports/

7. Kudrati, M. (2021). Explained: Why India Is Now An ‘Electoral Autocracy’ According To V-Dem. [online] Boomlive.in. Available at: https://www.boomlive.in/fact-file/explained-why-india-is-now-an-electoral-autocracy-according-to-v-dem-12306/

8. The city Delhi, as we know today, includes the seven, smaller, ancient cities (Delhis) within its bounds – hence, the use of ‘Delhis’

9. Dupont, V., Tarlo, E. and Vidal, D. (2000). Delhi: Urban Space And Human Destinies. New Delhi: Manohar.

10. Volwahsen, A. (2004). Imperial Delhi. Munich: Prestel.

11. Grbin, M. (2015). Foucault and Space. Socioloski Pregled.

12. Roychowdhury, A. (2021). From Kingsway to Rajpath: How independent India made a British imperial city its own. [online] The Indian Express. Available at: https://indianexpress.com/article/research/from-kingsway-to-rajpath-india-gate-how-independent-india-made-a-british-imperial-city-its-own-7315789/

13. Gupta, N. (1994). Kingsway to Rajpath: The Democratization of Lutyens’ Central Vista. Asher, Catharine B and Metcalf, T R (eds). Perceptions of South Asia’s Visual Past, Delhi.

14. Bhowmick, S. (2016). Princely Palaces In New Delhi. Niyogi Books.

15. Roychowdhury, A. (2021). From Kingsway to Rajpath: How independent India made a British imperial city its own. [online] The Indian Express. Available at: https://indianexpress.com/article/research/from-kingsway-to-rajpath-india-gate-how-independent-india-made-a-british-imperial-city-its-own-7315789/

16. BusinessToday.In. (2020). Delhi saw over 12,000 protests in 2019; highest in eight years. [online] Available at: https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/trends/delhi-saw-over-12000-protests-in-2019-highest-in-eight-years/story/393713.html

17. Vale, L. (2008). Changing Cities: 75 Years of Planning Better Futures at MIT. MIT.

18. Zieleniec, A. (2018). Lefebvre’s Politics of Space: Planning the Urban as Oeuvre. Urban Planning.

19. Nagy-Zekmi, S. (2008). Paradoxical Citizenship: Essays on Edward Said. Lexington Books.

20. Soja, E. W. (2009). The City and Spatial Justice. Justice et Injustices Spatiales.

21. Edelman, M. (1988). Constructing the Political Spectacle. University of Chicago Press.

22. Minkenberg, M. (2014). Power and Architecture. New York: Berghahn Books.

23. Parkinson, J. R. (2014). Democracy and Public Space: The Physical Sites Of Democratic Performance (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press.

24. Soja, E. W. (2009). The City and Spatial Justice. Justice et Injustices Spatiales.

25. Design Commission. (2015). Designing Democracy: How designers are changing democratic spaces and processes. Policy Connect. https://www.policyconnect.org.uk/apdig/sites/site_apdig/files/report/497/fieldreportdownload/designingdemocracyinquiry.pdf

26. Al-Kodmany, K. (2016). New Suburbanism. Routledge.

27. Benton-Short, L. (2016). The National Mall: No Ordinary Public Space. University of Toronto Press.

28. DiConsiglio, J. (2016). The National Mall: Inside America’s Front Yard. [online] Columbian.gwu.edu. Available at: https://columbian.gwu.edu/national-mall-inside-america%E2%80%99s-front-yard

29. Vale, L. (2005). Securing Public Space [Awards Jury Commentaries]. University of California.

30. Bhakat, R. (2020). What a Comparison of Great Central Vistas Tells Us About Modi’s Plans for New Delhi. [online] The Wire. Available at: https://thewire.in/urban/what-a-comparison-of-great-central-vistas-tells-us-about-modis-plans-for-new-delhi

31. Graham, S. (2015). Homeland/Target Cities and the “War on Terror”. In: Berking, H., Frank, S., Frers, L., Löw, M., Meier, L., Steets, S. and Stoetzer, S. ed. Negotiating Urban Conflicts. Bielefeld: transcript-Verlag, pp. 289-304. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839404638-021

32. Vale, L. (2005). Securing Public Space [Awards Jury Commentaries]. University of California.

33. Elliot, P. (2021). The Breach of the Capitol Spooked Us — As It Should Have. [online] Time. Available at: https://time.com/5927664/capital-siege-trump-supporters/

34. Kelly, M. (2021). What The U.S. Capitol Looks Like Ahead Of The Inauguration. [podcast] All Things Considered. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2021/01/15/957371199/what-the-u-s-capitol-looks-like-ahead-of-the-inauguration

35. Evenson, N. (1998). The Indian Mletropolis: A View towards the West. London: Yale University Press.

36. Lefebvre, H. (1976). Survival of Capitalism. Allison & Busby. pp. 88-9.

37. Design Commission. (2015). Designing Democracy: How designers are changing democratic spaces and processes. Policy Connect. https://www.policyconnect.org.uk/apdig/sites/site_apdig/files/report/497/fieldreportdownload/designingdemocracyinquiry.pdf

38. Parkinson, J. R. (2014). Democracy and Public Space: The Physical Sites Of Democratic Performance (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press.

39. Benton-Short, L. (2016). After 9/11, Public Spaces No Longer Represent Freedom. [online] Time. Available at: https://time.com/4482672/public-space-after-september-11/

40. Marcuse, P. (2015). Terrorism and the Right to the Secure City: Safety vs. Security in Public Spaces. In: Berking, H., Frank, S., Frers, L., Löw, M., Meier, L., Steets, S. and Stoetzer, S. ed. Negotiating Urban Conflicts. Bielefeld: transcript-Verlag, pp. 289-304. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839404638-021

41. Vale, L. (2005). Securing Public Space [Awards Jury Commentaries]. University of California.

42. Nehru, J. (1945, August 14) Inaugural Speech [Speech audio recording] All India Radio https://soundcloud.com/allindiaradionews/pt-jawaharlal-nehrus-tryst-with-destiny-speech

43. Dasgupta, S. (2014). A language which is foreign to us: continuities and anxieties in the making of the Indian Constitution. Comp. Stud. South Asia, Afr. Middle East 34(2):228–42.

44. Sengupta, A. (2021). Rite of passage. [online] Telegraphindia.com. Available at: https://www.telegraphindia.com/opinion/rite-of-passage-the-second-coming-of-the-constitution/cid/1813172

45. Soja, E. W. (2009). The City and Spatial Justice. Justice et Injustices Spatiales, 56–72

46. Parkinson, J. R. (2014). Democracy and Public Space: The Physical Sites Of Democratic Performance (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press.

47. Lefebvre, H. (1977). Reflections on the politics of space. In R. Peet (Ed.), Radical geography (pp. 339–352). London: Methuen and Co.

48. Zieleniec, A. (2018). Lefebvre’s Politics of Space: Planning the Urban as Oeuvre. Urban Planning.

+

The research for this piece is part of the author’s Graduate Thesis project at the Department of Urban Design, School of Planning and Architecture, Delhi.

Anavil Ahluwalia is an architect and urban designer based in Delhi. A graduate of the Urban Design Department at School of Planning and Architecture (SPA, Delhi), her thesis explored connections between the practice of urban design & our aspirations for democracy and spatial justice. With a keen interest in urban research, she hopes to continue her exploration of political urban space and the agency it offers to the citizen through an interdisciplinary approach between political and urban theory. She is currently working on the research project ‘Urban Transformations and Placemaking: Fostering learnings from South Asia and Germany’ at SPA Delhi in collaboration with Heidelberg University and Kathmandu University.

Volume 4, no. 1 Spring 2021