The Fine Line Between Protection and Citizen Control in Beirut

Kamila Bak, Rita Berisha and Anna-Maria Grimm

During the speech addressing the Protests in Lebanon in October 20191, Lebanese President Michel Aoun announced, “I heard many voices calling for the toppling of the regime. Regime change, young fellows, does not take place in the streets”2. This indication may leave one with the assumption that the protests actually created pressure on the government. The president’s strong denial highlights the importance of public space during the demonstrations, space that has always been central to the exercise of power in Beirut’s history. At that point, demonstrations had already been taking place on Beirut’s streets for a week, blocking traffic routes, closing shops and thus partially shutting down the economy. The protests were largely peaceful and united a wide cross-section of Lebanese society.

Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, is a city of various religious, cultural, political and economic groups. The city is home for more than two million people3, and was once known as ‘Paris of the Middle East’, a fashionable holiday destination to many Europeans and Americans, and also the publishing and entertainment capital of the Arab world4. However, the city has undergone major changes in the last 30 years, due to political conflicts. One of the biggest consequences was the Lebanese Civil War in 1975, lasting until 19905. In those times, the vital and social street life was depleted with the loss of many public and open access spaces, a process which Sara Fregonese, author of War and the City, considers ‘Urbicide’, violence against the built environment6. This warfare strategy targets city fabric and socio-spatial arrangements instead of the residents directly, which makes living together in an urban context more difficult. Cities, rather than state borders, are becoming increasingly important as the arena of conflict in times when urban areas are growing and with more complex conflict parties are involved. Saskia Sassen describes these shifting zones of conflict as “the partial unbundling of the traditional territorial national borders and the formation of new bordering capabilities”7. In modern day Beirut, it appears that in situations of political tension, the usual response of the authorities is omnipresent surveillance of public areas. Most recently, among others, the ongoing political corruption and plans to impose new taxes caused demonstrations lasting several months 8. starting in October 2019, which led to further security measures that once more limited the accessibility of open spaces. These places are crucial in the city’s urban structure, as they are main gathering points and are significant in citizens´ connection to the society9. Despite its large size, there are not many public spaces in Beirut. This shortage is mostly resulting from car-focused urban planning, lack of spatial regulations and negligence of public areas10. Moreover, the insufficiency of open access spaces gives the ones that already exist much more significance, as they are essential meeting points and are the sole areas where people can gather without consuming anything. But in a city like Beirut, still highly divided through sectarian differences, these places are also treated as a political arena. As a consequence, they are focal points in arising disputes and thus highly controlled and supervised by the government.

Conflicts within an urban context change the rules of mobility management, control and everyday life of inhabitants. This paper offers a glimpse into how the urban structure of Beirut, influenced by decades of hostilities, was used as a security measure during the first phase of a long series of protests in 2019 and 2020. It begins with a brief introduction to present-day Beirut, and how the city’s history has influenced current events, focusing on the 2019 protests, and urban planning solutions that may exemplify planning centred on maintaining order. In the course of this paper typologically different urban spaces will be examined, starting from the main squares, considered to be the heart of the city, where different ways of controlling their users were applied and which also became the main spaces of demonstrations. The streets as a public space, on the other hand, were often used to draw the attention of the inhabitants to current affairs. The last typology that will be discussed in this text are city parks. This leads to the conclusions of how control, or lack thereof, by the government and administration in various urban spaces affects the individuals living in Beirut, and how the city structure is being used to monitor its inhabitants.

This paper is the result of an urban planning seminar with an emphasis on showing the addressed problem by mapping. The research was based on a series of short lectures and seminars conducted partly in collaboration with the Académie Libanaise des Beaux Arts. The paper furthermore connects field impressions mapped and photographed by the authors during the research trip to Beirut in November 2019, with literature research on the context of the conflict. Since a main goal of the paper is to retrace major urban planning strategies implemented as security measures during the different stages of the conflict, maps constitute a main medium of information transfer in this report. Therefore, different urban typologies in Beirut, such as public spaces, abandoned buildings, streets and green spaces, were examined for their surveillance and security capabilities.

The background of the October 2019 protests

To better understand the impact of the changing urban landscape, it is necessary to shed some light on the context of the political climate during the 2019 Protests in Beirut. During this time the dissatisfaction among Beiruti with the political and economic downward spiral that their country was heading on had been increasing. It was especially aggravated when the government was unable to extinguish fires that emerged in Chouf and Saadiyat. As a result, many people not only lost their homes, but also had their lives endangered. Similar wildfires also happened days before the protests started. Then, due to a lack of equipment (including three donated firefighting helicopters that were unusable due to the lack of maintenance), Beirut was not for the first time saved by the support of its neighbouring countries11. Meanwhile the prices of oil and bread kept increasing and the unemployment rates reached 25%12. The citizens’ access to electricity and drinking water was at that time already limited, but its worsening added more fuel to the anger against the government. As the country’s state revenue and GDP reached their lowest point since 2008, the government was looking for ways to get those numbers back up. Their suggested strategy was to increase the taxes to 15% by 2022, with the final session of the budget draft to take place on the 19th of October 201913.

That seemed to be the last straw which caused the protests in Beirut to begin on October 17, 2019, forcing the meeting of the government to be cancelled. “For 30 years, we’ve been living in this same corrupt system, and now there’s not even money left for them to steal anymore”, Semaan Khawami, 45, an artist and protester, told the New York Times during the demonstrations. “So now they’re coming up with new ways to steal from us”14. Tens of thousands of Beiruti were ready to tirelessly protest for their rights and demanded that the government, that brought their country in this situation, would step down15. The city’s squares and streets quickly filled with people demonstrating, chanting, and reappropriating public spaces on a daily basis for months. Conquering these spaces turned out to be no easy feat; after all, the city offers little open space for public use. Many squares, such as Martyrs Square in the city centre, served primarily as parking lots. Therefore, solely occupying the space happened to be the form of protest.

Martyrs Square during the protests with tents built by volunteers in the back. 2019. Source: Maram Batta

The Green Line flashback: how modern Beirut is affected by its history

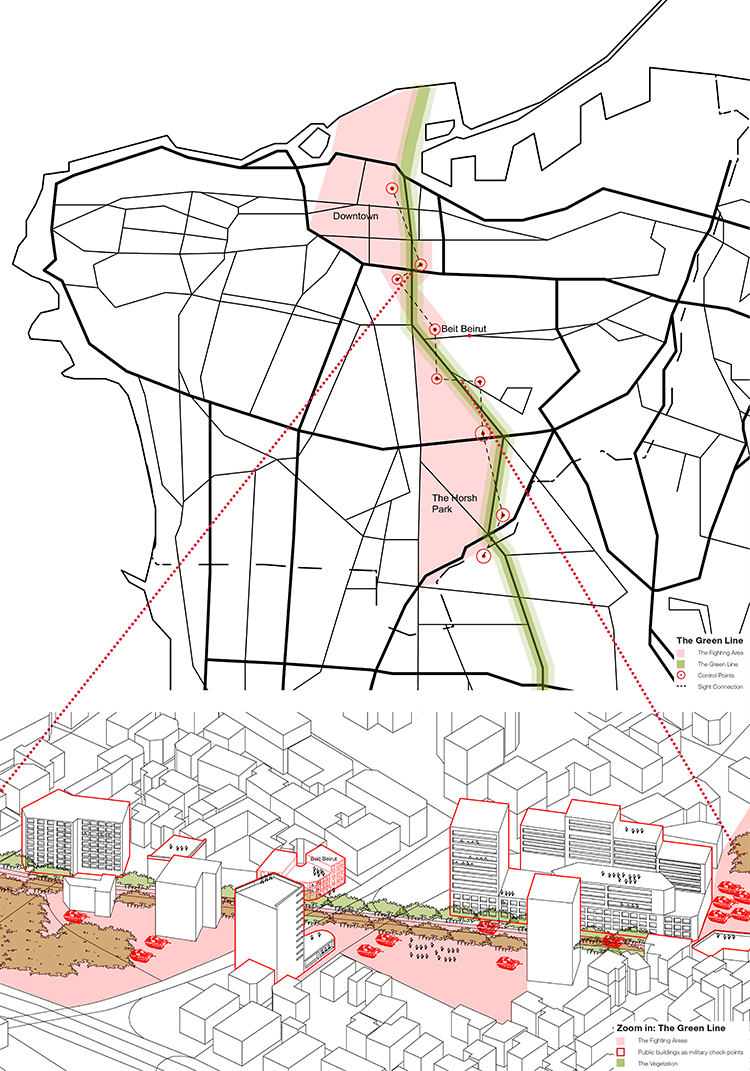

The structural problems of the ongoing social and political situation in Beirut seem to have their roots in the past, long before their present formation. One of the main events that raised controlling behaviour in the city to a higher level was the Civil War. The marks that it left behind still follow and define the city’s current situation when it comes to securing safety and keeping violence absent. In 1975 the city became the territory of war and Damascus Road, separating the Christian majority east, and Muslim majority west of Beirut, became the main stabilization of a confrontation line16. This 8 km long strip of land became a no man’s land, and was given the name of ‘the Green Line’, as vegetation grew there in the absence of traffic17. Museums, schools and many other public buildings that adjoined the line were extremely damaged. Many of them changed their function and were used as bunkers, shields for sniper fire and as storage spaces for weapons. This way not only did they fall victim to the war but were used as instruments of it. The Green Line was a highly controlled area with many checkpoints on both sides. They were constantly monitored by the militias in order to entirely supervise the area and ensure that no one was able to cross the line without being seen18. Even 10 years after the Civil War ended, Syrian soldiers were still seen at certain checkpoints in this area. Supervision strategies used during the war were still present in Beirut long after the war ended19.

The harsh level of control was a form of assurance that the two opposing sides of the city would not meet. It also represents the foundation of Beirut’s government mentality. Some of the methods used during the war are being used by the government nowadays in order to avoid social conflicts and misbehaviour. Although in October 2019 the country was not in a state of war, the protests, public gatherings and overall tense social situation prompted the government to follow its old pattern and use the city, its infrastructure and architecture, as a management machine against its citizens.

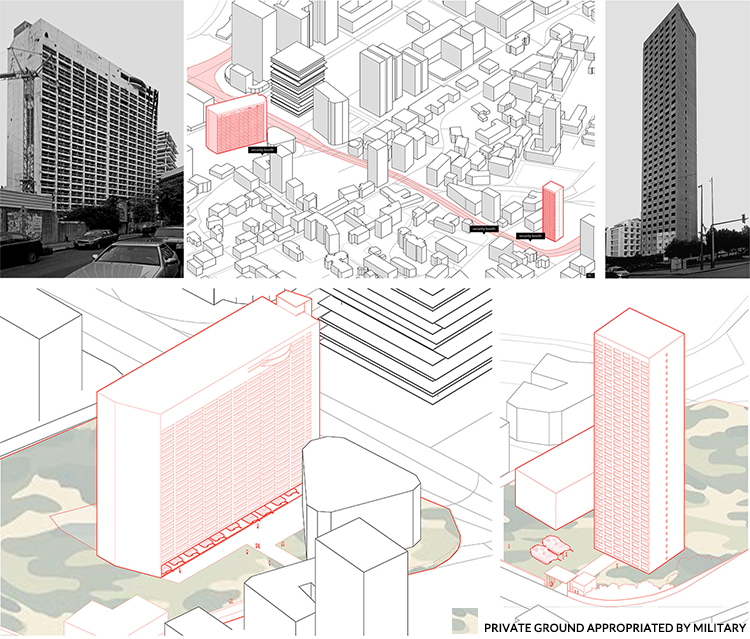

This surveillance might not always be repressive, but the quantity of control in one particular part of Beirut is striking. Zaitunay Bay, an outstanding area concerning this topic, is a dense quarter of high-rises designed by internationally renowned architects. The most prominent ones being Beirut Terraces by Herzog & de Meuron and Foster and Partners’ 3Beirut. Close to these exclusive residential buildings there are number of empty skeleton volumes with bullet-perforated facades remaining from the time of the Civil War. Two of them, the Murr Tower and the former Holiday Inn, were a central fighting ground during the Lebanese Civil War. They were used as sniper towers, as they offer a good overview of the adjacent terrain, mainly the highway and the part of the Green Line in the city centre20. The former Holiday Inn is also a representation of Beirut’s years of prosperity, having been commissioned by a Kuwaiti investor for 20 million Lebanese Liras. It was designed by a student of Le Corbusier, Andre Wogensky, one year before the Civil War, and shortly after, it has been casting its shadow over Beirut as a memorial to the conflict21. The rule over the towers still seems to be very symbolic, as it is still under military control today. During the protests in 2019, they were supposedly used as outlook posts and were equipped with tanks and soldiers, a presence that might change public behaviour around the area22. The soldiers were closely monitoring people photographing the buildings. While taking photos close to them, phones and cameras were inspected in order to search for pictures of military presence, despite the fact that the buildings are still privately owned.

One of the recurrent patterns is the increased scrutiny of residents’ private lives during conflicts. The diversity of the city’s inhabitants, and differences between them were historically considered the greatest source of disagreements. The authorities try to keep the city in check and limit contact by excessive displays of supervision, checkpoints on the highways, the re-purposing of high-rise buildings, and the constant presence of the army and the police on the streets. This way of silencing these disputes has worked in the city for years, but its effectiveness was challenged during the protests of October 2019, which instead of dividing Beirut’s social groups, united a wide array of people in the name of fighting against corruption and oppressive political tactics.

Militarization of the Fakhreddine highway as a public space and on private grounds at the former Holiday Inn (left) and Burj Al Murr tower (right), November 2019. Source: Authors

Building walls as a response to the protest around Nejmeh Square

When Beirut residents took to the streets, parks and squares during the protests, they met with different responses from the city authorities. First of all, the government wanted to keep these public spaces ‘safe’ or empty, like before. As a result, they decided to pacify the crowds by heavily armed militia, but also by installing cameras and closing parts of the city.

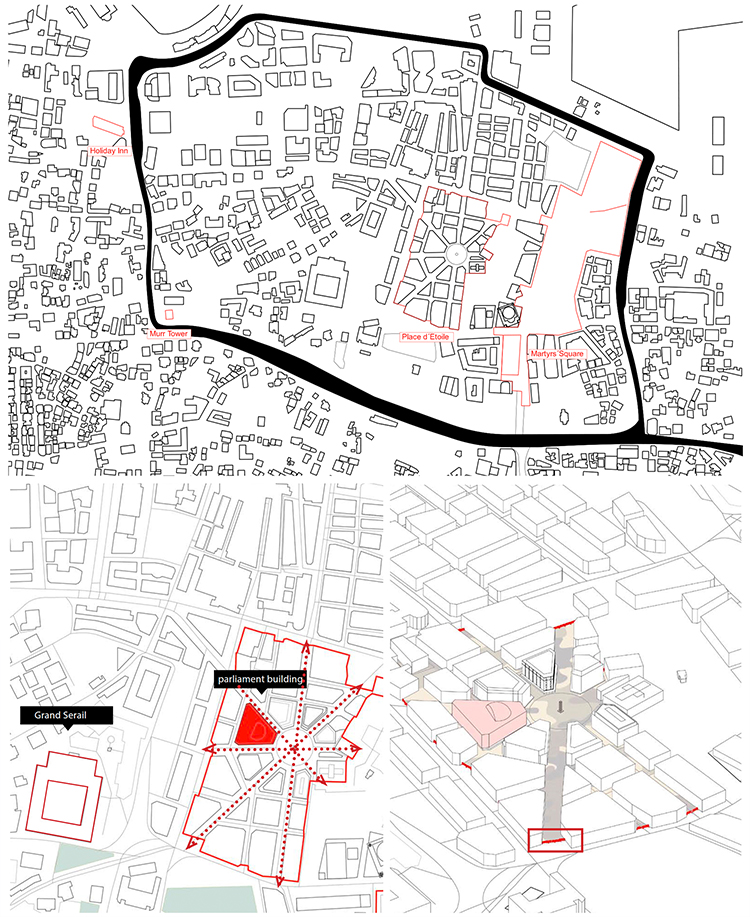

The Nejmeh Square is the heart of Beirut Central District, containing the capital’s landmark, a 1930s clock-tower, and the Lebanese Parliament Building. Other governmental and cultural buildings are situated adjacent to this square, as well as the nearby Government Palace Grand Serail. The importance of its surroundings makes the area a high-risk zone with a need for protection and supervision of governmental security forces. It is noteworthy that, while securing the area around the Nejmeh Square, the city was being fortified at almost the same spots where its defensive ninth-century walls stood until they were dismantled in the early 1900s; Beirut’s present-day inhabitants were now recast as its past invaders.

Relevant areas of control in and around the ring road surrounding the city center of Beirut and the layout of Nejmeh square, November 2019. Source: Authors

After its destruction during the Lebanese Civil War, the space was redesigned in a similar way as it was during the French colonisation between 1920 and 1943. In the square’s layout, one can already see a soft security strategy integrated into its design. The star shape of the square, and the street protruding from it, gives a good overview over the area from its central point leaving almost no space unsupervised. The buildings around the plaza also cover the central governmental building from possible hazard of attack.

Moreover, long distances between access points to the quarter and the buildings of importance are typical for high security zones. In her book The Insecure City23 Kristin V. Monroe traces this kind of approach back to the Civil War: “During this time [the civil war], as during the protracted civil and regional war (1975–1990), the vehicular bomb was the signature means of violence: in almost all cases, individuals were killed or injured while driving, being driven, or passing by cars”24. In this manner, blast zones of possible detonations are implemented into the design.

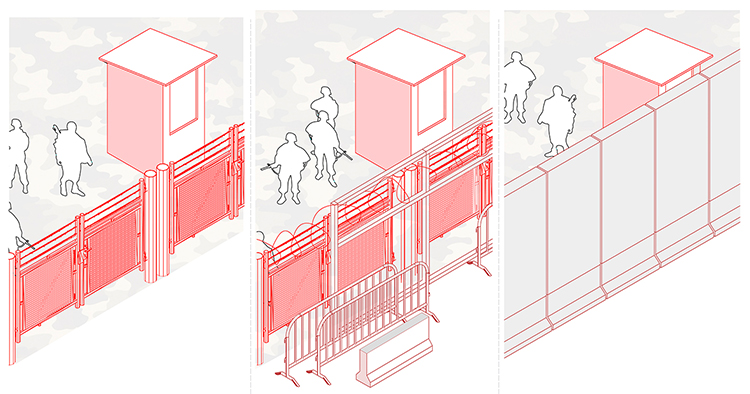

When political tensions rise, tighter security measures such as fences, checkpoints and security guards tend to be added on top of soft design ones in the square. The entrance to the area around the Nejmeh Square was first restricted by officials in 2014 following ‘security threats by extremist organizations’25. During the Garbage Crisis in 2015, security measures were tightened by adding metal barriers, heavy concrete blocks and restricted entrance for visitors, in order to prevent protests from taking place there. For many companies around the square that also meant a shutdown26. Security was also tightened during election phases, in 2016, when “employees had to walk to reach their offices downtown, as all vehicles were banned from entering the area. Security forces set up metal detectors along the streets around Parliament as army helicopters could also be heard hovering overhead”27 After a ‘decline in security threats’28, on the last day of 2017, the square was reopened for the public for a New Year’s Eve celebration with music, fireworks and dancing. Unfortunately, the square, and the area surrounding it, were gradually closed again. Most often, only foreign tourists were allowed to enter the area, while Lebanese residents were usually denied, which shows a pattern of granting unequal access to the main square.

With the argument that public places and government buildings could be used as targets of physical violence, tough measures can regularly be justified, resulting in a changed perception of these public places through their accessibility. At the beginning of the 2019 protests, the area surrounding the Nejmeh Square was completely closed for visitors in order to prevent demonstrations in front of the parliament. The quarter was protected by high fences with gates on each entrance. Additionally, soldiers were lining the gates and metal barricades were erected. The security measures were tightened even more as a reaction to the outburst of violence between protestors and the military in January 2020. The gates on the entrances of the area around the square were not just closed, but also reinforced with barbed wire and steel frames. On January 23, additional concrete blast walls were erected.

The closure of the centre and building of walls were some of the government’s responses to the notedly peaceful demonstrations. The ease with which the square and surrounding quarter was closed during the protests shows that securing the area was a basic design parameter. Other urban spaces, like the nearby Martyrs Square, where the protests took place, leave more room for appropriation.

Equating a place with the protest: reclaiming Martyrs Square

As Sara Fregonese explains in War and the City, many urban planning changes in Beirut were justified with the civilization mission of colonizing countries and explained as sanitation and beautification measures29. This way the traditional souks (markets) in the city centre of Beirut got replaced by a large town square design under Ottoman Governor Azmi Bey, whose modernization projects were later continued by French colonial forces.

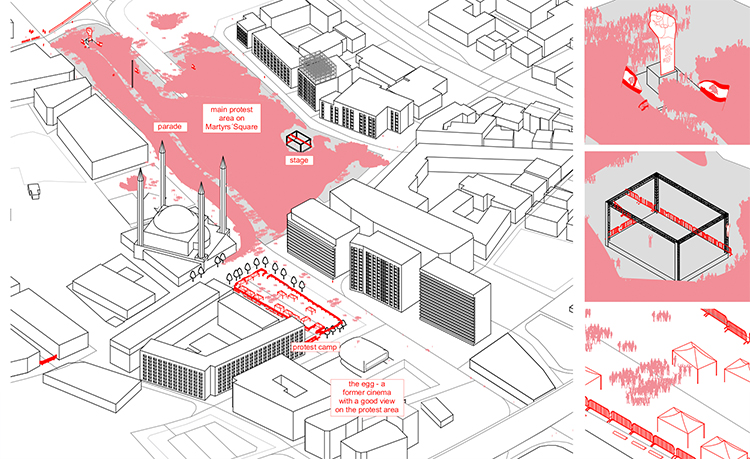

In the 19th century the Martyrs Square, located on the border of Beirut’s Central District, was modernized and intended as the main meeting point in Beirut, and therefore was flooded with people, cinemas and coffee places30. Later, the location served as a bus terminal, meanwhile still being a popular venue for both Beiruti and tourists. During the Civil War, the place became a part of the demarcation line and was cut off from the city. This formerly vibrant place was then abandoned for many years to come. After its reconstruction, the square became the urban centre of the area, with its axis reaching the sea31. With its extensive layout and lack of surrounding services, the square did not regain its pre-war character and in the meantime, its main function has become a parking lot. Design strategies that would lead to more interactions, like benches, cafes or green spaces, were omitted, probably planned with the expectation that people would not linger around and that the square would be used for parking cars. “Downtown Beirut was turned by the oligarchy into a major real estate project … [and it] emptied the city centre of the popular classes […]The tents set up during the revolution attacked this model, and helped bring back regular people to the heart of the city. They helped regain privatized public spaces”, economist Jad Chaaban told CityLab32.

The monumentality and openness of the square emphasizes its representativeness but also prevents the space from being easily closed off, which provides more leeway for protesters to assemble there. Since the beginning of the protests in October 2019, large rallies and parades had regularly taken place on the square, turning it into the focal point of demonstrations. A statue of a hand clenched into a fist, the symbol of the protests, was erected in the centre of the area.

Unlike the Nejmeh Square, this place was protected, to a far lesser extent, by groups of police officers on the periphery of the square. In addition, the protesters themselves became the main guards, keeping order and organising the residents. The strikers opened tents where various discussions, rallies and deliberations on the future of the country took place. Thousands of Beirut’s residents joined this movement of struggle for change in government and politics. Unfortunately, over time conflicts between protesters and counter-protesters escalated, making the initially peaceful demonstration difficult to navigate for the protestors themselves. The counter-protesters perpetrated destruction and damage to most of the tents and attacks on the marchers. This intensified police control and introduced stronger means of dispersing the demonstrations, such as tear gas.

The presentation of protest on Martyrs square with protesters’ tents and stage, November 2019. Source: Authors

The meaning of the street: use of street space during the protests

Beirut is a very car dependent city and commuting by car is the main means of transport, since there is almost no public transportation system in the city. The primary highway system functions as the main connection between the remote areas of the city with its centre. It also encloses the Beirut Central District, filled with public, cultural and entertainment institutions, which also host numerous protests. The ‘Ringroad’ highway as an enclosing element is a sort of a barrier33 separating the inside and outside of Beirut‘s Downtown and regulating access to it. This makes the highway infrastructure a highly vulnerable area in the city, which is especially apparent, when the street is blocked. Security measures around this area were tightened during the conflicts of 2004 to 2006. Then, commuting through the city changed due to the installation of barriers, blockades, checkpoints and the rerouting of traffic flow34.

Although the epicentre of the 2019 protests became the Martyrs Square, the streets also played a huge role, which brought lots of changes to the daily lives of Beirut’s residents. Major streets of the downtown area became the site of the protest march, with many of them severely impeding movement in the city. Protesters erected makeshift barricades and burned tyres to oppose the power of the elite ruling the country. The highways leading into the city, as well as the Ringroad mentioned above, were also stalled, with blockades set up at equal intervals along several kilometres of the road.

At this time, the internet was flooded with pictures and videos of the crowd marching the streets. It was almost impossible not to meet the people protesting. That shows how effective reclaiming public spaces is in sharing one’s message and how fast it can spread nationwide. At the moment of vulnerability and of an all-too-visible threat to their own sovereignty, people decided to reclaim the public spaces, by blocking the streets in order to salvage the feeling of control, restore the sense of self and power of community and make themselves heard.

Park maintenance and denial of access to Beirut’s citizens

Discussing public spaces in Beirut, it is of great importance to mention green areas. Due to the heavy urbanisation of Beirut and profit oriented private investment, the green spaces in the city are remarkably scarce. In the capital’s downtown they are mostly manicured, tiny gardens, beautiful but offering little to passers-by. The majority of municipally owned gardens are opened to the public only for a certain amount of time during the day, and in some cases only to specific social circles. Consequently, city residents, supported by voluntary groups and NGOs, often raise the issue of parks and voice their beliefs and concerns through a range of meetings and rallies.

What is first visible in the already existing gardens, private or public, is fencing topped with sharp elements. Another feature are the guards standing at every entrance, looking at every one that is about to enter the park. Everything is aimed at keeping people, especially kids playing inside, safe and free from verbal and physical violence. The purpose of this closure, ordered by authorities, is preventing public drinking, vandalism and inappropriate behaviour35.

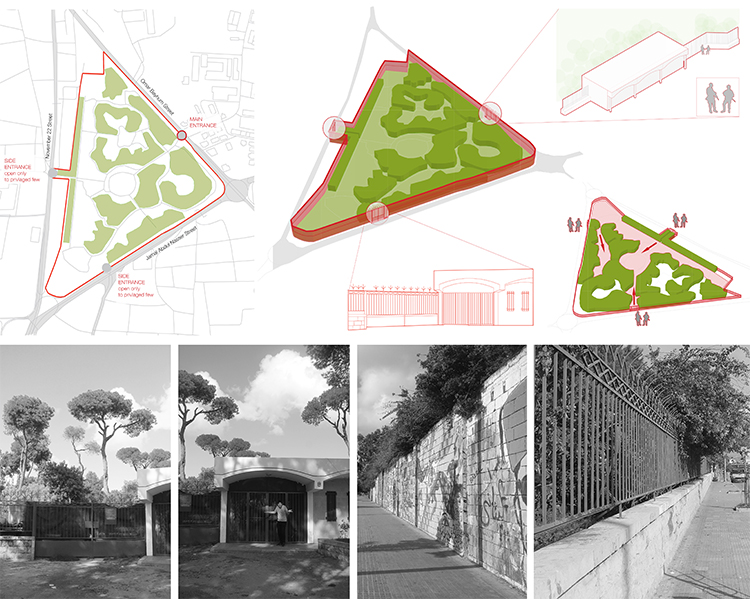

Horsh Beirut, the biggest public park in Beirut, has a very troublesome history of accessibility, but, at the date of writing, it has its gates open to almost everyone for some time of the day. The park was once a vast forest of pine trees, a remarkable green space in the south of Beirut. Over the years, it shrank in size and in the 1960s36 became an official public park owned by the municipality. The park was destroyed during the Lebanese Civil War, which has resulted in the closure of the park for reconstruction and reforestation. The park remained accessible for another 25 years only to those privileged few, who gained the permission to enter37. Authorities feared exposing this oasis of peaceful greenery to everyone. As an aftereffect the park was erased from citizens’ memories for almost 40 years. Thanks to the exceptional efforts of one of Beirut’s NGOs, Nahnoo, Horsh Beirut was gradually reopened to the general public in 201538.

Already prior to the reinstitution of the park, the NGO suggested a scheme and structure for protecting and monitoring the space and restraining visitors from unwanted actions. They also created a behaviour control charter to be followed strictly when using the park. The charter’s paragraphs include naming the park to be a no-arms zone, as well as not allowing fires to be started for any reason, and it also determines specific areas that are restricted from being walked in. Violation of these rules would result in severe fines39. Present day Horsh Beirut is a very well maintained, gated public park opened to the public on weekdays between 7 am and 1 pm, and on weekends between 7 am and 3 pm40, which all together provides 46 hours a week of peaceful leisure to its visitors.

Currently, there are three main entrances to the park area. Although only the east entryway serves for the general public, the others remain closed and are privileged, private entrances. At the gate there is a special guardhouse for the military controlling the access to the park. The whole park area is surrounded by a fence more than 2 meters high, that is also topped with sharp elements. The restricted opening hours also make it difficult for the average Beirut’s citizen to visit the park, as it is mostly open during typical working hours. While visiting Horsh Beirut on a sunny Sunday in November, it was very striking to see how vacant it was. There were groups of people walking and sitting along the main routes, or making small picnics close to them, but in the park as a whole, there were not many visitors. Horsh Beirut is the biggest green space in Beirut, and one may think it should bring many more people inside its gates. On the other hand, all the measurements taken by authorities to maintain Horsh Beirut as non-violent and secure, may be leading to visitors feeling (over)protected, safe but also observed.

The ways of reclaiming this park are very different from the protests described earlier. It is mostly a long bureaucratic struggle of volunteers and activists who want to give this one big green corner of the city back to its citizens. In its long history, the park has been greatly diminished in size by the growth of built-up areas. Therefore, reactions to the introduction of opening hours as well as the attempt to build a hospital in part of the park in 2017 resulted in people taking to the streets and demanding their rights more loudly and directly via protests.

The response of the authorities to the protests

The residents of Beirut were fighting for their rights within the city on multiple levels during the course of the protests. They wished to physically reclaim lost public places like Martyrs Square and Horsh Park, spaces often reduced through urbicidal practices. Likewise, streets almost entirely cut off for pedestrian traffic and public transport, leaving space only for moving cars, were repurposed by protesters, who aimed to draw public attention to the city’s existing problems. At the same time, residents loudly expressed their dissatisfaction over the economic and fiscal state of the country. They turned against their country’s rulers, pointing out mistakes which, committed by them over many years, have significantly worsened the social situation of a great part of Lebanese society.

Even though the protests were peaceful, the military and police forces used excessive violence against the protesters, with beating and pellets, and by shooting rubber bullets and tear gas canisters directly into the crowd. Although there were instances where vandalism and minor conflicts were caused by the protesters (or counter protesters), these statistics should not have resulted in demonstrations being declared unpeaceful41.

Through months of continuous protests, the streets of Beirut were flooded with thousands of people, but the city itself froze. Shopping centres and schools were closed and it became impossible to withdraw money from banks as they were shut down for weeks. This stagnation of the city definitely affected the daily life and financial situation of the inhabitants. It has also affected the economic situation of the state, which has only increased the people’s discontent. Although the months spent protesting in the streets did not lead to a total change of government, Beiruti might have experienced a glimmer of hope, which could have ignited visions of a better future for Beirut. Reiterating President Aoun’s words, “regime change does not take place in the streets”42, the contrary happened in Beirut. The street protests ultimately united many people in Lebanon and led to the partial resignation of the government.

The protests of recent years have highlighted that the control infrastructure from the civil war within the past decades has been developed to fit the purposes of current day police and military personnel in Beirut. The need for constant control of the population through checkpoints, access restrictions and direct attacks on crowds has become a typical response of the authorities to the gathering of crowds during protests. After all, the easiest way to restrict access to public places is to close them off completely or to create uninviting ones, whether through barricades or urban planning solutions. It turns out that urban planning decisions very easily influence the characteristics of a space, as can be seen from the example of the two squares described earlier. On the other hand, it also became prevalent that protesters started to use the existing urban space for their own purposes. The community showed that socially lifeless places can become alive again, even if only to become a stage for protests.

As a result of the accidental explosion in the summer of 2020 and COVID 19 pandemic, the city will be faced with new challenges, and the question emerges: how can Beirut thrive on the basis of this changed urban fabric? The protests showed there is an unusual sense of common purpose uniting different parts of the Lebanese society, which might enable renegotiations on the remaining shared spaces.

Notes

1. Bak, K., Berisha, R. & Grimm, A.-M., 2020. Controlling Beirut, Karlsruhe: Karlsruhe Institut of Technology.

2. THE DAILY STAR Lebanon News, 2019. [Online] Available at: https://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2019/Oct-24/494235-aoun-regime-change-does-not-take-place-in-the-streets.ashx [Accessed 11 02 2021].

3. United Nations, 2018. The World’s Cities in 2018. [Online] Available at: https://www.un.org/en/events/citiesday/assets/pdf/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf [Accessed 11 02 2021].

4. MONROE, K. V., 2016. The Insecure City. 1st ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey, London: Rutgers University Press, p. 30.

5. Ibid. p.36.

6. Fregonese, S., 2019. War and the City: Urban Geopolitics in Lebanon. 1st ed. London: I.B. Tauris: Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 40.

7. Sassen, S., 2005. When National Territory Is Home to the Global: Old Borders to Novel Borderings. W: New Political Economy 10, No 4. Published online: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563460500344476: Taylor & Francis Online, p. 524.

8. Aljazeera: News, 2019. [Online] Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/17/protests-erupt-in-lebanon-over-plans-to-impose-new-taxes [Accessed 13 06 2021].

9. Nazzal, M. & Chinder, S., 2018. Lebanon Cities’ Public Spaces. The Journal of Public Space, 3(1), 30 04, p. 122.

10. Ibid. p.119.

11. Azhari, T., 2019. Aljazeera. [Online] Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/16/lebanon-wildfires-hellish-scenes-in-mountains-south-of-beirut [Accessed 13 06 2021]

12. Hamadi, G., 2019. An-Nahar. [Online] Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20200721215655/https://en.annahar.com/article/1004952-unemployment-the-paralysis-of-lebanese-youth [Accessed 22 04 2021].

13. THE DAILY STAR Lebanon News, 2019. [Online] Available at: http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2019/Oct-17/493731-cabinet-meets-as-backlash-grows-over-tax-proposals.ashx [Accessed 13 06 2021].

14. Yee, V., 2019. The New York Times. [Online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/18/world/middleeast/lebanon-protests.html [Accessed 13 06 2021].

15. Chehayeb, K. & Sewell, A., 2019. Foreign Policy. [Online] Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/02/lebanon-protesters-movement-streets-explainer/ [Accessed 11 02 2021].

16. Fregonese, S., 2019. War and the City: Urban Geopolitics in Lebanon. 1st ed. London: I.B. Tauris: Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 145.

17. Dundon, R., 2018. Timeline. [Online] Available at: https://timeline.com/daily-life-continued-in-beirut-during-civil-war-37ad777d9ea8 [Accessed 13 06 2021].

18. MONROE, K. V., 2016. The Insecure City. 1st ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey, London: Rutgers University Press, p.43.

19. Ibid. p. 47.

20. Fregonese, S., 2019. War and the City: Urban Geopolitics in Lebanon. 1st ed. London: I.B. Tauris: Bloomsbury Publishing, p.161.

21. Ibid. p. 160.

22. Nayel, M.-A., 2015. The Guardian. [Online] Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/may/01/beirut-holiday-inn-civil-war-history-cities-50-buildings [Accessed 11 02 2021].

23. MONROE, K. V., 2016. The Insecure City. 1st ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey, London: Rutgers University Press, p.80.

24. Packer, J., 2006. BECOMING BOMBS: MOBILIZING MOBILITY IN THE WAR OF TERROR. In: Cultural Studies, 20:4-5. Published online: https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380600711105: Taylor & Francis Online, pp. 378-399.

25. Asharq Al-Awsat, 2018. [Online] Available at: https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/1132896/lebanon-reopens-entrances-downtown%C2%A0beirut-after-4-years-closure [Accessed 11 02 2021].

26. Mosendz, P., 2015. Newsweek. [Online] Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/beirut-trash-protests-wall-365546 [Accessed 11 02 2021].

27. MONROE, K. V., 2016. The Insecure City. 1st ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey, London: Rutgers University Press, p. 91-111.

28. Albawaba: Your gateway to the middle east, 2016. [Online] Available at: https://www.albawaba.com/news/security-tightens-lebanon-tries-once-more-end-presidential-vacuum-898976 [Accessed 11 02 2021].

29. Fregonese, S., 2019. War and the City: Urban Geopolitics in Lebanon. 1st ed. London: I.B. Tauris: Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 35.

30. MONROE, K. V., 2016. The Insecure City. 1st ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey, London: Rutgers University Press, p. 155.

31. Sharif, A., 2018. The culture trip. [Online] Available at: https://theculturetrip.com/middle-east/lebanon/articles/a-brief-history-of-beiruts-martyrs-square/ [Accessed 13 06 2021].

32. Chehayeb, K., 2019. Bloomberg. [Online] Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-31/beirut-s-protesters-assert-their-right-to-the-city [Accessed 13 06 2021].

33. Ramirez, E. O., 2018. Culture in city reconstruction and recovery: position paper. 1st ed. Paris and Washington DC: UNESCO and THE WORLD BANK.

34. MONROE, K. V., 2016. The Insecure City. 1st ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey, London: Rutgers University Press, p. 91-111.

35. WHO, 2016. The World Health Organisation: Europe. [Online] Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/publications/2016/urban-green-spaces-and-health-a-review-of-evidence-2016 [Accessed 11 02 2021].

36. Saksouk, A., 2013. Dictaphone Group. [Online] Available at: https://dictaphonegroup.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/90/2018/12/SIM-booklet-compressed-1.pdf [Accessed 11 02 2021].

37. em>Next City, 2015. [Online] Available at: https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/closed-to-the-public-for-decades-beiruts-only-park-may-re-open-this-year [Accessed 11 02 2021].

38. Shayya, F., 2006. Enacting Public Space History and Social Practices of Beirut’s Horch al-Sanawbar, Beirut: American University of Beirut.

39. Next City, 2015. [Online] Available at: https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/closed-to-the-public-for-decades-beiruts-only-park-may-re-open-this-year [Accessed 11 02 2021].

40. NAHNOO, 2017. [Online] Available at: http://nahnoo.org/our-causes/horsh-beirut/ [Accessed 11 02 2021].

41. Amnesty International, 2020. [Online] Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/08/lebanon-military-and-security-forces-attack-unarmed-protesters-following-explosions-new-testimony/ [Accessed 28 02 2021].

42. THE DAILY STAR Lebanon News, 2019. [Online] Available at: http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2019/Oct-17/493731-cabinet-meets-as-backlash-grows-over-tax-proposals.ashx [Accessed 13 06 2021].

+

The work presented in this article is based on the seminar “Metropol.X” held by Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Kamila Bak is a Berlin- based architect, she recently earned her Masters in Architecture and Urban Design from Wrocław Institute of Technology. Originally from Poland, she did a study exchange in Germany where she focused on research about the impact of architectural and urban planning decisions on the city residents. During her course of studies she developed interest in accessible architecture and introducing appropriate spatial and visual arrangements into the design to improve daily lives of people with special needs. She focuses on the importance of light and meaning of colour in the interior, in order to achieve better movement and orientation in the buildings. With learnt passion for art and science, she appreciates the advancement of technology, like VR and BIM, to create complex and full-experience designs and well-coordinated projects.

Rita Berisha is an architecture student currently in the Master’s Program in “Karlsruhe Institute of Technology”. Born and raised in Prizren, Kosovo, she was awarded a full scholarship by the “German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD)” to pursue with her studies in Germany. After graduating with a Bachelor’s Degree in Architecture, she went on to work as an intern in different firms there as well as in her home country. Having worked on many projects as part of university assignments and in the professional field, she aspires to play a role in developing sustainable architecture into a common sense, while managing to maintain its artistic, creative, and innovative sides. Showing a notable interest in architecture throughout history and cultures, she hopes to learn from them and help make this field find a safe balance and dynamic with nature itself, while making the design of exceptional spaces and buildings more accessible to people all over the world.

Anna Grimm recently graduated with a Master’s degree in Architecture from Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. She also studied at Tongji University Shanghai and Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg. Currently, she lives and works in Berlin. During her studies, she developed a keen interest in urbanism and governance issues. Her master thesis project on the reuse of an animal testing facility in Berlin was recently shown within the exhibition “Mäusebunker und Hygieneinstitut” in Venice.

Volume 5, no. 1 Jan-Jun 2022