The Spatiality of 2019 Protests in Beirut

Nadine Hindi

On the afternoon of October 17th 2019, a long overdue protest swept all of Lebanon at once1. It spontaneously erupted across different cities and locations in the form of multiple decentralized protests, claiming the end of a political system perceived as sectarian and corrupt, and the establishment of a civil system, that would replace the sectarian-based political system. The protests kept going unabated for a few months until their momentum gradually decreased and intermittent lockdowns and curfews caused by the spread of Covid-19 brought them to a halt. The 4th of August 2020 Beirut Port explosion and its unprecedented scale of destruction2 was felt by many as the culmination of the Lebanese mental suffering brought about by a political class found accused of neglect and corruption leading to this disaster. Massive protests rallied following the Port blast calling for justice and a transparent investigation; they were suppressed by the brutal intervention of the army and the ISF (Internal Security Forces). The 2019 protests in Lebanon are a construct of social and civic problems that have remained unresolved since the civil war. Unlike the 2005 protests3 which split the citizens into two political camps, the 2019 protests rose with the uniting political slogan ‘kellon-yaani-kellon’, meaning in Arabic ‘all-means-all’ in reference to the political system as a whole, accused of significant corruption and fueling sectarianism since the end of the civil war. In the modern history of Lebanon following independence, this is the first protest that has united all Lebanese across all sects, religions and social classes. Protestors unanimously flooded the streets and the main squares in different cities across the country joining a global current of decentralized and horizontal leader-less demonstrations. For once, Beirut was not the spatial center of the protests’ geographical spread, yet, hosting the Parliament and Government offices, it remained the most important and emblematic node.

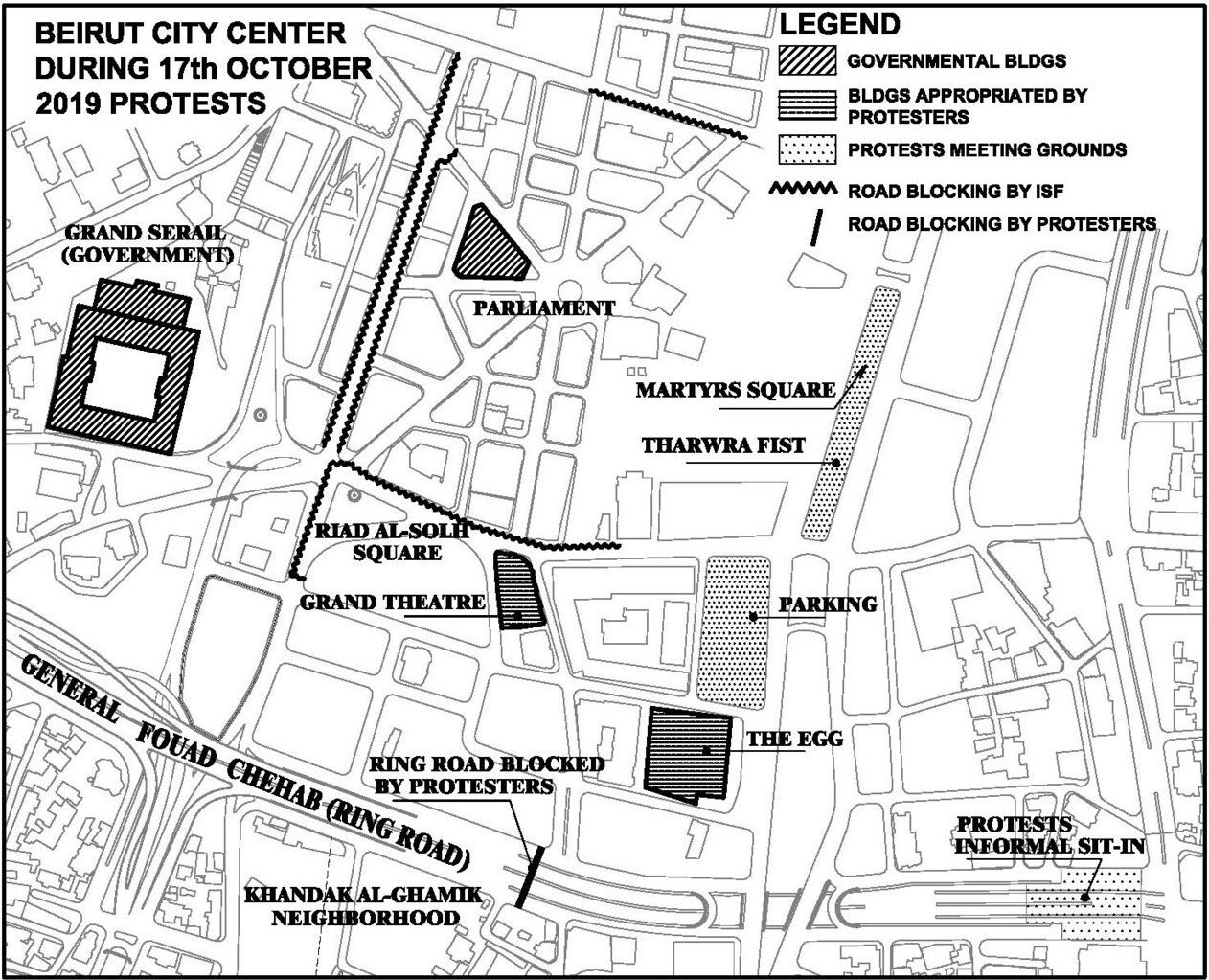

This article discusses certain spatial aspects observed during the first three months of the 2019 protests, through a twofold lens: first, it presents the urban spatial expression of the protestors, in the form of territorialization, squatting and celebration of the city; secondly it discusses the spatial counter-reaction of the ISF and the army in terms of passive and active forms of militarization and power delineation. Some observations are drawn on this new urban spatiality, expressed in different forms at various moments of the protests, notably with regards to the flexible thresholds and borders between the Sulta4 and people, and their impact.

Territorialization and city squatting

The reconstructed Beirut city center privileges capitalist private interests over public ones. In line with this capitalist and neoliberal development models, the post-war Solidere master plan abolished the significance of the city as a public core and an inclusive socio-political ‘commons’5. Furthermore, the master plan prioritized the construction of high-end residential and office buildings while the public spaces of the center, mainly Martyrs Square, remained neglected throughout the reconstruction phase – the square was alternatively ‘reconstructed’: it was reclaimed as the main gathering platform for all the civic protests since 2005. The city center’s transformation was completed with its gradual militarization under the pretext of various security aspects6: from barbed wires, barricades and concrete blocks, militarization reached its peak with the assembly of opaque concrete walls between the buildings representing the political power and the citizens7.

Unlike the 2015 YouStink and We-Want-Accountability demonstrations, the 2019 protests did not focus on the ‘right to the city’; while calling for broader socio-political change they informally transformed the space of the city into an inclusive platform for gatherings and dialogues across the sectarian groups. The protest movements materialized by territorializing and squatting the urban space in different ways, while remaining inclusive for all citizens. From the outset, two territories, two grounds, were self-organized in an unbuilt set of lots previously used as a parking space and in the hitherto neglected main square in the city, Martyrs Square.

The parking space in proximity to the ‘the Egg’ structure became a host for open public debates: temporary tents for civic society activists, university academics, NGOs and representative social clubs, were pitched; it was appropriated as an active sociopolitical meeting area for open discussions of civil rights issues coming from the grassroots. Several open debates and critical discussion events were organized within the space of ‘the Egg’ itself.

Simultaneously, Martyrs Square, the most emblematic square in the city, became the main protest’s gathering place equipped by protesters with a giant screen where demands were voiced. The protests were peacefully celebrated in this square which regained its role as the main public space in the city, a space for all. It was at once the camping place where youth and activists spent their nights, and a celebration space for the recurrent massive gatherings of Sunday afternoons and special occasions such as the Independence day celebration on the 22nd of November. The installation of the Thawra fist8 symbol, decisively marked the square and completed the territorial re-appropriation of the space.

Martyr Square gathering ground with the Martyrs’ sculpture to the left and the Thawra fist to the left. November 2019. Source: Author

Apart from a violent first night, when the ground floor of one of the most expensive residential development projects in Beirut, was deliberately set on fire, the protesters strived to keep a peaceful and inclusive image. They territorialized, colonized, squatted and re-appropriated the city making every effort to keep their presence peaceful. The protesters employed creative ways in colonizing the city’s streets, such as a yoga sit-in that blocked the Ring road9, one of the main city arteries, in an attempt to change negative perceptions of road blocking, reminiscent of the civil war city division10, by staging events that can peacefully unite people. Informal street vendors, long excluded from the high-end streets of the city center, complemented the protests’ spontaneous and authentic re-appropriation of street life. Graffiti on the walls increasingly marked the protesters’ re-appropriation of the city, complemented by artwork pieces created out of their burnt and destroyed tents11 following attacks against them at several occasions. Damaged buildings from the civil war battles, that had remained at a war-scarred condition, like the ‘Grand Théâtre’ and the famous structure known as the ‘the Egg’, were peacefully re-appropriated. The latter was used as an informal cultural-political meeting ground in proximity to the outdoor tents space.

Citizens reclaiming the Egg structure, visiting the top and meeting inside. November 2019. Source: Author

The protest movements managed to self-organize themselves into an informal and peaceful re-appropriation of the city, up until the initiation of cycles of violence triggered by the orders of the ruling political class to end the demonstrations and clear the road blockades. Empowered by a spirit of freedom of expression, freedom to dissent, which finally unified them all over common causes, the Lebanese were collectively breaking divisions fueled by years of a sectarian-based rule. Accordingly, their use of the city space was a spatial celebration of their civil right to protest and manifest their claims. During the first two to three months of the protests the city’s self-organized spatial order enabled the inclusion and access of all citizens in and to all open spaces, even previously inaccessible gardens and streets.

Gebran’s garden near Escwa building, became accessible for the public during the protests period. November 2019. Source: Author

Militarization as an urban order

The daily practices of the protesters imposed a new spatial reality in the city center and its immediate surroundings. The political class was deeply opposed to the claims, first aiming to passively de-territorialize and dismantle this urban squatting, before resorting to force as a second step. It deliberately turned a blind eye to acts of terrorizing the protesters by different means. From the outset, undeclared partisans of political parties12, related to Hezbollah and Amal parties, attempted to lay a climate of terror on the protests’ gathering grounds by destroying tents, burning the Thawra symbol, and assaulting the protesters themselves. Allegedly aiming to restore road traffic, the supporters of the political system and followers of Amal party from Khandak el-Ghamik13, a neighborhood at the immediate vicinity of the Ring road, attacked peaceful demonstrations at several occasions. Located at the immediate fringe of Solidere area, this neighborhood is at once underprivileged and stigmatized, shelled to a great extent from its proximity to the confrontation lines during the civil war. Not yet politically neutralized, it remains to date a ‘dormant faultline’ 14, triggered and activated during the demonstrations15.

Violence and counter-violence actions escalated as the army used force to break the human chains of protesters formed at the roadblocks. Probably the most violent confrontations took place around the roads and squares leading to the Parliament building and the Grand Serail (Government building), both symbols of the ruling class. As confrontations escalated between the protesters and the ISF, the latter resolved to using water cannons, followed by tear gas and finally rubber bullets to disperse the protesters away from the territory around the Parliament and the Government building. In an already securitized Beirut16, the spaces in-between activists and political power were further marked with borders and militarized. Barricades, barbed wires and concrete walls were laid down around the Parliament and the Government areas. The more citizens claimed back their Parliament, the higher the defensive walls were raised. The militarization of Beirut is the result of recurrent confrontations in the same urban spaces since 201517. Failure to reconcile the city center with the citizens at large during the peacetime and reconstruction period, transformed it into a space at once vulnerable and hostile.

The Government Serail in the background is separated from Riad al-Solh square by barbed wires. November 2019. Source: Author

Walls replaced the barbed wires around the Government Serail in the background and the road leading to the Parliament to the right. November 2019. Source: Author

Conclusion

Two years into the beginning of the 17th of October upheaval movements, the protests gradually stopped yet their demands remained unaddressed. Instead, a sociopolitical division of Beirut’s city center prevailed, separating the governing political system and the citizens into two territories hostile to each other. The Government premises located on a slight hill, along with the Parliament building, were isolated from the rest of the city within a militarized island territory, while the protesters’ grounds remained fluidly connected to the rest of the city. An unsettled atmosphere hitherto prevails over the city center where most of the buildings have become unoccupied following the combined effect of cycles of clashes between government forces and protesters, a deep economic crisis, and the significant damage generated by the Port explosion of the 4th of August 2020. From the outset, the protesters temporarily reconfigured the city center through different forms of spatial appropriation, squatting and territorialization, as part of their daily practices. Despite the temporary nature and ambivalent outcome of the 17th of October upheaval, this spatial reconfiguration succeeded to transform the protests’ grounds into a collective mental and physical space for spontaneous dissent against the political system; it transcended sectarian boundaries and initiated a new culture of space; its long term significance and impact on the city remain to be seen.

Notes

1. Locally referred to as the 17th of October upheaval or revolution, it is a series of civil protests initially triggered by increased taxes, corruption and declining civil services. It led to the resignation of the government cabinet in November 2019 and the formation of a new one, which resigned in its turn following the 4th of August 2020 Beirut Port explosion.

2. On the 4th of August 2020, an explosion rocked Beirut caused by the explosion of hazardously stored ammonium nitrate at the Port, to be considered as one of the most powerful non-nuclear explosion in history.

3. Following the assassination of prime minister Rafic Hariri in 2005, a series of protests rose in Beirut, divided over the presence of the Syrian military presence in Lebanon. While the 8th of March coalition claimed for the Syrian presence, the 14th of March one rallied for the withdrawal of all Syrian troops and realized their goals few days following their massive protest.

4. The term Sulta, literally meaning Rule in Arabic, became commonly used in Lebanon in reference to the whole ruling political class, in one word.

5. Harvey, D. (2013). Rebel cities. London: Verso.

6. Fawaz, M., Harb, M. and Gharbieh, A. (2012). Living Beirut’s Security Zones: An Investigation of the Modalities and Practice of Urban Security. City & Society, 24(2), pp.173-195.

7. Brighenti, AM & Kärrholm, M. (ed.). (2019). Urban Walls. Political and Cultural Meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces. New York: Routledge.

8. Thawra means revolution in Arabic. Despite burning the fist’s sculpture several times by unknown thugs, it has been redone and re-installed in its place within hours.

9. “Lebanon protesters get creative, use yoga to block roads” 2019. Gulf News, October 28. Available at: https://gulfnews.com/world/mena/lebanon-protesters-get-creative-use-yoga-to-block-roads-1.67447447

10. During the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990) Beirut was divided along a demarcation line, punctuated by access points and checkpoints, controlled by militia men from both sides.

11. “Beirut protesters’ camp attacked, tents set on fire: TV footage” 2019. Reuters, October 29. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lebanon-protests-fires-idUSKBN1X81HE

12. “Khandak el-Ghamik: the other side of the thawra” 2019. L’Orient Le Jour, December 18. Available at: https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1199084/khandak-el-ghamik-the-other-side-of-the-thawra.html

13. Khandak el-Ghamik is a Shi’a neighborhood in Beirut that supports Hezbollah and Amal parties, situated at the immediate vicinity of Ring road blocked by protesters.

14. Silver, H., 2010. Divided Cities in the Middle East. City and Community, 9:4 December (DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6040.2010.01348.x.).

15. Hindi, N., 2021. Beiruts, Grüne Linie; Entgrenzung und Kotroversen an der Demarkationslinie des Bürgerkriegs. In Bernhardt, C., Schlusche, G., Butter, A. & Klausmeier, A. (Eds.). Die Mauer als Ressource: Der Umgang mit dem Berliner Mauerstreifen nach 1989. Berlin: Ch. Links, pp.42-55.

16. Fawaz, M., Harb, M. and Gharbieh, A. (2012). Living Beirut’s Security Zones: An Investigation of the Modalities and Practice of Urban Security. City & Society.

17. Leontidou, L. (2006). Urban social movements: from the ‘right to the city’ to transnational spatialities and flaneur activists. City, 10:3 (DOI: 10.1080/13604810600980507.), pp. 259-268.

Nadine Hindi, Dr. is an architect and an urban designer, currently an Associate Professor at Notre Dame University in Lebanon, at the department of Architecture since 2015. Holder of a Bachelor degree in Architecture from the American University of Beirut, she pursued a Master and a PhD degree in urban regeneration at the University of Barcelona in Spain. Her research and publications focus on urban topics including urban forms, urban history, war geography, public spaces and waterfront cases. She organized and participated in international workshops with her students and attended international seminars and conferences. She has been an invited speaker at public lectures in cities like Berlin, Weimar, Barcelona, and Amman, and contributed to community serving by co-organizing training modules to a local NGO on the right to public and waterfront spaces.

Volume 5, no. 1 Jan-Jun 2022