Coopelluvia: facilitating urban water commoning

– Stephanie Newcomb

Southern California—specifically Los Angeles—is no stranger to water scarcity. To sustain a growing population, a hyper-centralized infrastructural utility network sources water through three aqueducts from the San Joaquin Delta, the Owens Valley and the Colorado River—fed by the Colorado Rocky Mountains. The aqueduct infrastructure and conveyance of water is extremely energy-intensive and affects the city’s ability to adapt to a changing climate. The region’s scarcity has been felt more intensely when coupled with increasing variable precipitation patterns, last visible in the previous “drought”1 years 2011-20172.

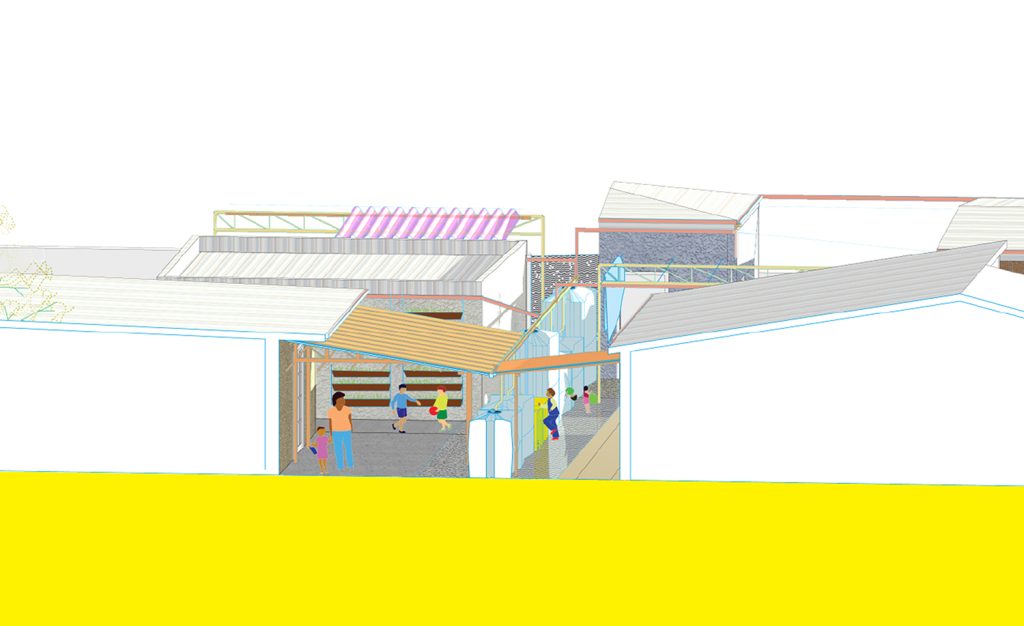

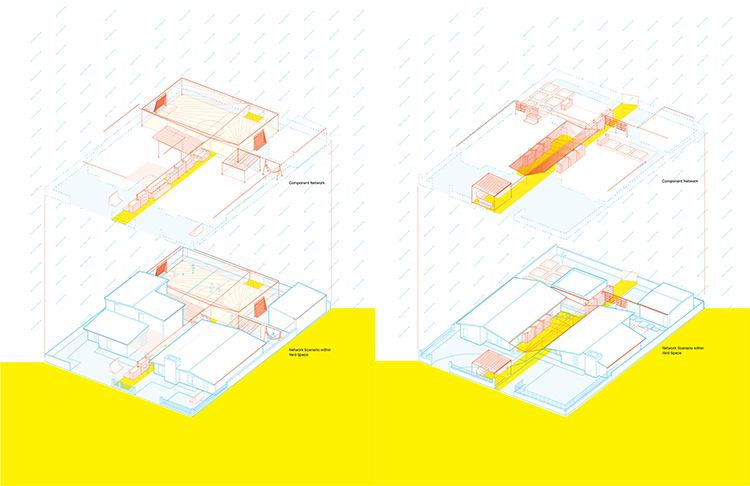

Maximizing rainwater capture is an important strategy in creating a resilient Los Angeles. Current city and county stormwater capture plans3 focus on maximizing water capture on public land, however private property water capture is an untapped opportunity for creating localized networks [Image 1]. Focusing on the San Fernando Valley Tujunga Watershed—part of the Upper Los Angeles River basin—the project situates in areas where the soil composition or levels of underground contamination are not suitable for groundwater infiltration, therefore stormwater is best when locally stored above ground.

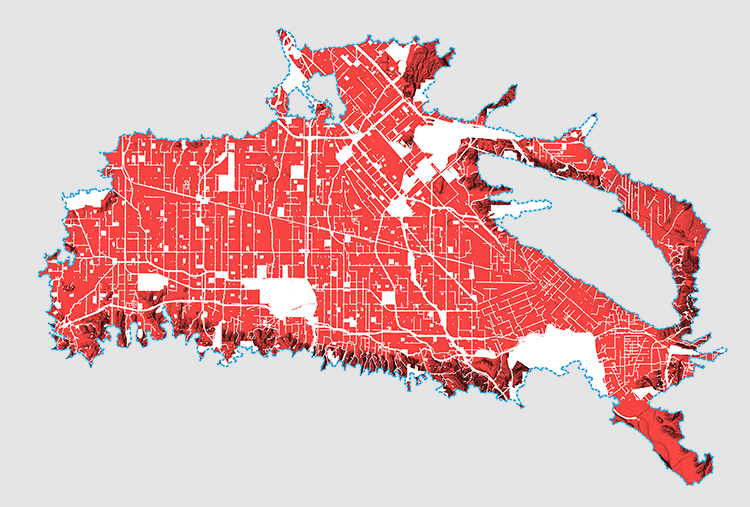

Coopelluvia is a hyper-local networked rainwater supply model that offers a complementary alternative to the water infrastructure network of Southern California. The project aims to provide a decentralized system for active citizens who want to source water, primarily for outdoor use—thus decreasing the embodied energy and carbon emissions produced by imported water—provide an activist strategy for rain water rights, reduce downstream flooding (less saturation in the storm pipe network) and to increase the resource’s visibility—understanding the watershed cycle as well as the relationship between above-ground and underground water [Image 2].

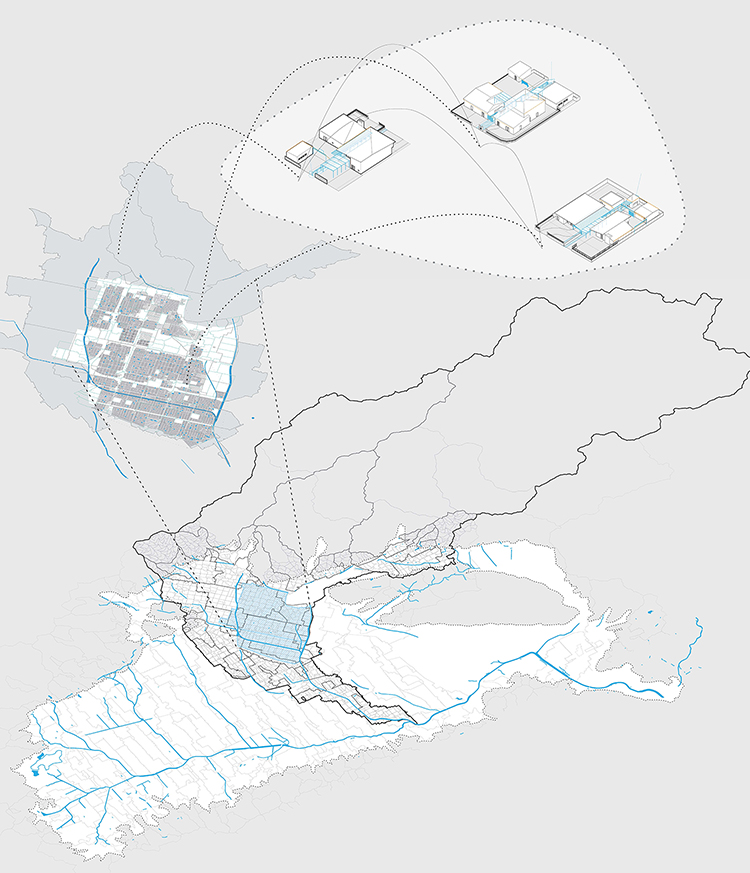

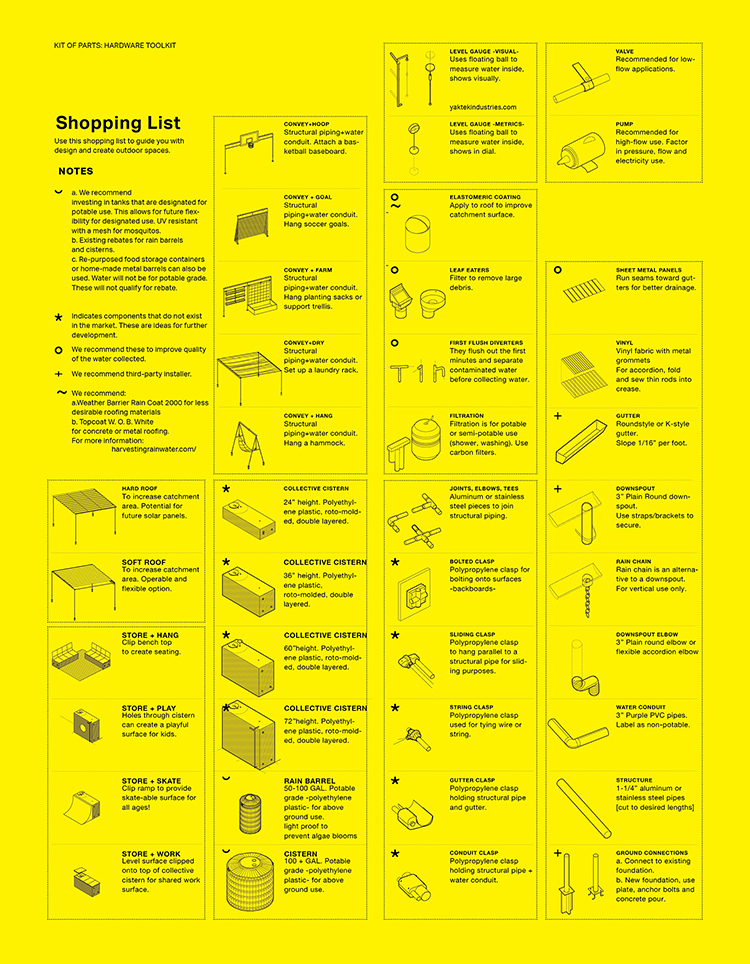

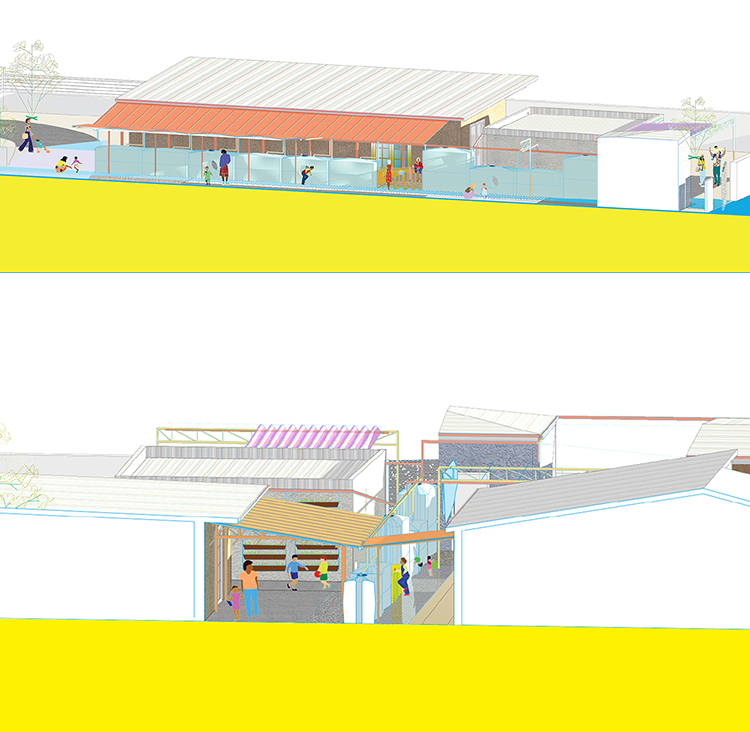

As a toolkit for application between single-family houses, it leverages on a hydro-social space where local water storage is combined with social amenities. Single-family plots have a difficult time allocating space for both water storage and social space. Many households are limited to rain-barrels or cisterns that either fill up after a rain event or disrupt their yard. Many single-family neighborhoods lack parks, green areas and public spaces at a convenient walking distance. In many households, the fence is an already observed informal place of interaction for garage sales, cultural expression, gossiping, drying clothes, a place to sit or play a game of chess [Image 3]. The fence is at the threshold of domestic private property: a comfortable point for social interaction between the yard and sidewalk. By interpreting the fence as a storage system made up of a flexible set of water cisterns and its connecting parts [Image 4], water as a resource is situated at the center of conversation between neighbors. The toolkit promotes a shared social space that maximizes under-used space as an opportunity for water storage, creating opportunities for ecological and social communal use [Image 5,6].

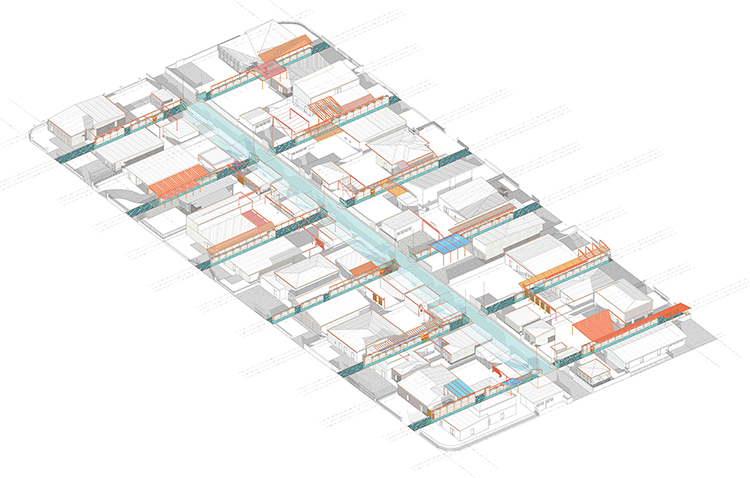

By blurring the notion of private and public property and instilling a sense of localized ecological and social resilience of water management, the participating neighbors become active citizens in their ability to maintain, adapt and develop an ecological and cultural identity and critical knowledge of practices. Although Coopelluvia focuses on the lowest common denominator of private to public threshold—the fence—[Image 7,8] there is an opportunity to also expand into a greater catchment area. Larger clusters of homes or the city block scale [Image 9] can gather and store larger amounts of rainwater, but require more responsibility, accountability, investment and care. Integrating commoning principles4 can be a way to create functional and alternative administrative boundaries that are attuned to the watershed health, manage the hardware of the Coopelluvia toolkit and create a resilient network between neighbors advocating for effective rainwater capture. Ideally, a commoning network can share information, resources and operational values that can transcend into greater accountability and responsible stewardship of the neighborhood and districts.

Image 1. A composite public land and infrastructure map [in white] through the San Fernando Valley Basin is the primary target of existing plans for stormwater capture. The areas highlighted in red are all the private properties. The SFV is a 225 square mile sediment filled basin part of the watershed for the LA River. The goal is to capture and store water on site and lessen the strain on the public infrastructure with the added benefit of a local source of water for outdoor use.

Image 2. The scales of governance are both political and hydrological as well as above ground and underground — referring to property lots, drainage basins, sub-watershed and watershed boundaries, neighborhood and districts, areas of optimal infiltration, areas of contamination, soil composition and city limits. Pacoima and Arleta are the two neighborhoods used as a case study since they are both located within the same sub-watershed and exhibit similar conditions of having a highly urbanized and residential development with large areas being impermeable and prone to flooding near the tributaries.

Image 3. Observed evidence of the following in the Pacoima-Arleta neighborhoods within the San Fernando Valley: Informal social space in a domestic and public domain, sense of cultural pride, underused open space, indications of adaptation mentality, observations of DIY construction techniques, organization and political will, social cohesion, strong environmental and social justice networks, visible connections between built environment and social and environmental goals.

Image 4. Shopping list of hardware parts that could be used in the ad-hoc construction to renovate a couple of single-family dwellings into a shared water capture device. Some of these items are existing off-the-shelf products, while others will need to be further developed and produced.

Image 5, 6. Toolkit deployment examples of two single-family houses sharing a shared water storage system. Shared social programming can include small urban farm lots, shared space for laundry areas and playgrounds—amenities especially sought after in neighborhoods with younger demographics and low public amenities.

Image 7, 8. Montages of threshold space show the multiple interpretations that can stem from re-thinking the cistern. Starting at the smallest scale through the coupling of residential properties is a bottom-up approach to creating the possibility of an alternative system.

Image 9. In a span of 10 years, the city block can grow and adapt a commoning model that re-uses the alleyway as a storage space but also a shared social space. A reclaimed alleyway can provide shared amenities especially beneficial in park poor areas. Several city blocks can adopt the model, however linking between them would be rather difficult from a hardware and governance perspective. The city block is treated as the maximum allowed scale to keep a sense of local pride based on adjacency rather than leading to disinterest.

Notes

1. Referred to as “drought” because water scarcity is the new normal. Existing infrastructures are calibrated to a presumed natural cycle that fluctuates within an unchanging envelope of variability, also known as stationarity. However, the effects of climate change have impacted the envelopes of variability.

See more in Milly, P. C. D., Betancourt, J., Hirsch, R.M., Falkenmark, M., Kundezewicz, Z.W., Letternmaier, D.P., Stouffer, R. J. ( 2008). Stationarity is Dead: Whiter Water Management. Science, Vol 319, pp. 573-574.

2. Through this period, most of the state—in particular the Southern part of the state—was under drought emergency.

Boxall, B. (2017).Gov. Brown declares drought emergency over. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-brown-drought-20170407-story.html [Accessed 4 Jan. 2020].

3. Stormwater plans include: The Greater Los Angeles County Integrated Regional Water Management Plan (IRWMP), Bureau of Sanitation and Department of Public Works Los Angeles Storm Water Program and Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) Stormwater Capture Masterplan.

4. Elinor Orstrom Design Principles give an insight into how to start a commons. See more in: Orstrom, E. (2000). Reformulating the commons. Swiss Political Science Review, pp. 29-52.

+

This project was conceived and completed as part of the M.S.Arch. Thesis at the Woodbury School of Architecture under the Arid Lands Institute, Los Angeles 2016.

Stephanie Newcomb is an architectural designer and researcher from Costa Rica / United States currently working and living in Zagreb, Croatia. She was a design-research assistant at the Arid Lands Institute in Los Angeles from 2015-2016. She has a B.Arch from Carnegie Mellon University and a M.S.Arch from Woodbury University.

Volume 3, No. 1 February 2020