Meanwhile Communities Network: Detecting and strengthening local communities through temporary re-use of vacant facilities in London

– Israel Hurtado Cola

In large metropolises such as London, the speed of urban regeneration is generally faster than anywhere else in the globe, due to the high pressure from both internal and external speculative agents. Every year, a compelling (but unknown) number of urban communities are threatened and even displaced to other parts of the city by the aggressive effects of the property market. In parallel, since 2010 there has been a rising tendency to blame the civic sphere for being an expensive and inefficient luxury, and therefore an increasing trend towards closing multiple public facilities across the UK, which stay unoccupied for long periods of time. This situation has been exacerbated by the current impact of Covid-19 on city centres, where thousands of public and commercial premises have been indefinitely vacated. ‘Meanwhile Communities Network’ proposes a platform with which to temporarily re-utilise this valuable catalogue of assets in order to revitalise local communities.

I. Introduction. Context

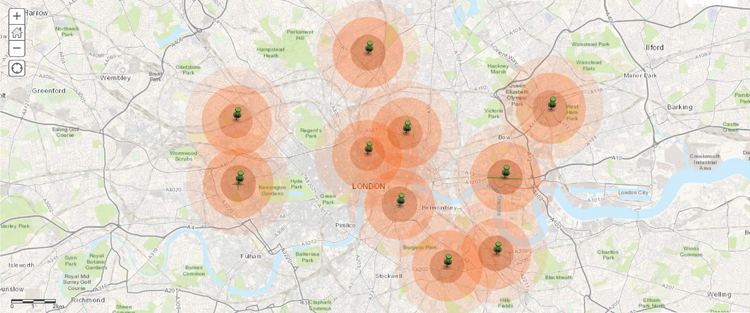

Our research started in 2018 in the context of austerity policies and gentrification, and focused on the closure of a large number of police stations and its impact on the local communities around them. We wanted to explore a systematic methodology with which to give a measurable visibility to these communities, while undertaking a comprehensive mapping of vacant civic properties across London. Our main driver was to find innovative methods for re-activating London’s extensive yet underused network of vacated buildings, with a focus on temporary civic programmes, establishing what we called the ‘Meanwhile Communities Network’.

Fast forward two years and add Covid-19 to the above scenario. Many more properties —this time not only civic but also a high number of commercial buildings— are presently being left unused for months, perhaps years. As the current crisis forces us to rethink the way we rebuild our cities, could this be a unique opportunity to regrow a more adaptable network of civic spaces, by making temporary use of the increasing inventory of empty premises?

II. The numbers. Voids growing at the heart of local communities

Following the Great Recession (2007-2009), the United Kingdom adopted an austerity programme based on sustained reductions in public spending and tax raises, aimed at reducing the government budget deficit. Between 2010 and 2019 more than £30 billion in spending reductions were made to welfare payments, housing subsidies and social services1.

According to the National Audit Office, local governments in England saw a 49% real-terms reduction in Government funding in the period from 2010–11 to 2017–18.As a consequence, more than 500 children’s centres and 340 libraries closed between 2010 and 2016, and numerous community and youth centres, public spaces and buildings including parks and recreation centres have been systematically sold off2. Another study conducted by the community network Locality in 2018 concluded that every year in the UK an average of 4,131 publicly owned buildings and spaces are sold to private agents3.

In November 2017 the Mayor of London decided that 38 of the 73 existing police stations were to be “disposed of” or not have their leases renewed, in order to overcome government cuts ‘by saving some £8 million’. Following this decision, a great number of them (26) were partially or completely closed down in the following months, awaiting sale or redevelopment. However, two years on (as of November 2019) only three of the closed stations had been sold4.

The majority of the remaining unsold (and unoccupied) buildings, of which a great number are of high architectural value, will likely stay unused for years before being converted into different types of private developments. It is believed that a similar lengthy process will follow the closure of other civic facilities, and not just police stations.

As of September 2020 the numbers in relation to Covid-vacated premises, both public and commercial, are uncertain and dynamic figures, that will only be accurately measurable in the coming months or years. But we can equally assume an interim scenario, ranging from 6 months to 2 years, where thousands of these properties will remain in disuse. Starting our study, we saw this long time-gap (between the sale or vacating and the redevelopment or re-occupation) as an unexplored waste of resources at a large scale, as well as a great opportunity to redesign the parts of the planning system concerned with temporary uses.

III. Meanwhile milieu. The London opportunity

The concept of meanwhile use, though it has become more widespread in recent years, is still fairly underused, too restricted by regulations and other socioeconomic barriers, and very often finds itself crystallised in small tokenistic interventions of limited community value. In 2018 the Centre for London think-tank published a detailed report on meanwhile uses in the London metropolitan area, and their potential. The study started by highlighting the difficulty of defining meanwhile use, as it “is a loose designation for activities that occupy empty space while waiting for another activity on site. The majority of meanwhile uses last between one and three years”5.

The elusive nature of the concept is also reflected in the broad list of accepted (legally and socially) space uses: Meanwhile uses range from small community gardens to large workspaces, and can be as diverse as permanent uses: London has pop-up shops, bars, allotments, art galleries, football pitches; as well as housing or workspace on a meanwhile basis6.

Their extensive survey detected 51 active meanwhile sites, with a combined floorspace of 188,600 sqm─the majority of them occupying sites with granted planning consent awaiting development7. But more interestingly, it found (in a pre-Covid era) that at least 20,000 commercial units in London had been empty for at least six months, and 11,000 for over two years─that is to say nearly three million sqm of floorspace in London with the potential to be occupied by community meanwhile initiatives8.

Meanwhile operators spend considerable time scouting for new sites, however information on empty commercial units is particularly difficult to access. London local authorities hold data about empty commercial units (since these are not liable for business rates), but they record it in different ways, some do not record it at all, and those that do generally tend to hold back information from the public to prevent squatters, theft and vandalising. As of June 2018, only the London Borough of Barnet published this data on a regular basis9.

IV. The legal framework. Obstacles to meanwhile

The same report from Centre for London identified and analysed some of the main barriers hindering the propagation of temporary use10. There seems to be a general consensus that it is harder, longer and more complicated to get planning permission for meanwhile use than for a permanent building, as they are expected to deliver immediate benefits in extremely time-sensitive scenarios.

Use classes, which define what type of activity is allowed on specific sites or buildings, often hinder meanwhile activity, as it is difficult to ask permission for an as-yet-undefined use. Typically, in large-scale meanwhile strategies there can be dozens of different uses in one site, each one needing a separate planning application─which often deters local entrepreneurs and investors. Licensing is also a big barrier for the meanwhile uses that need evening or late-night licenses to operate successfully.

Another crucial issue relates to leases. For sites that are under-used rather than vacant, current lease agreements do not allow tenants to sublet their slack commercial space without landlord consent, and landlords are unwilling to sublet below market values for fear that accommodating a sub-market element will cause an overall drop in the value of the space.

The property tax regime also limits the growth of non-residential meanwhile use. Currently, meanwhile activities are liable for business rates if the space they occupy was previously liable for business rates, regardless of whether the meanwhile activity is a business or not. This is a huge disincentive to providing non-market meanwhile uses─such as an exhibition or community space, as for many meanwhile projects the business rates bill is the main operational cost.

The current planning system also has the potential for perverse outcomes. For example, by demolishing a commercial building early, landlords can stop paying business rates, rather than giving the building over to meanwhile activity. Alternatively, many choose to install property guardians, making the building liable to council tax instead, which is up to 99 per cent lower than business rates.

V. New technologies. Towards a flexible and adaptive planning system

The rise of meanwhile activity in the last decade shows that there is indeed a real demand for more flexible and adaptable space, and an urgent need for spaces that straddle use classes which can be in turn a workspace, a garden and a nightclub within a day. Meanwhile use challenges conventional ways of city-making by putting the emphasis on immediate and real needs of locals, while testing the ideas and needs for the future through inexpensive and agile interventions. However, in order to maximise its potential, meanwhile use requires an unusually fast processing of information and a high level of adoption, which traditional planning practices can’t keep up with.

In this sense, a broad and connected network of meanwhile uses can be the seedbed for innovation that large dynamic cities like London need to thrive on. As a global conversation on Track & Trace digital applications has entered everyday public life, we can see how the development of many data-collection technologies may be substantially accelerated by Covid19.

In the context of community spaces and buildings (temporary or permanent), a huge amount of useful information can now be harvested on a daily basis, helping to visualise how people actually use spaces, and helping to accurately predict several transformation scenarios. The proliferation of new technologies is enabling more and deeper symbiosis between the digital and the physical realms, and provides people with greater access to knowledge and tools that were considered too complex or prohibitive in the past.

New digital tools will help generate real and informed placemaking, while enabling highly flexible and adaptive city-making processes that defeat the usual barriers to meanwhile use and other novel planning initiatives. Furthermore, digital technologies nowadays make it possible to broker or manage a large number of dynamic and multi-use spaces, even by small operators.

VI. How to maximise meanwhile─defining the parameters of our network

In order to overcome the described barriers to successful implementations of meanwhile use, and to magnify its advantages, we defined the following acting principles that will inform the architecture of our platform:

- Timespan of meanwhile programmes: between one and three years.

- Target assets: civic and commercial buildings or spaces that have been unoccupied for at least 6 months.

- Definition of the programme: the specific uses for each initiative will be defined by the local community through extensive data-based information.

- Meanwhile spaces will be operated by local groups.

- Proposals will aim for a highly flexible and innovative mix of uses, to enhance a more sustainable and resilient ecosystem of local and city-wide agents.

- Network structure and legacy: in order to guarantee the preservation of legacy beyond the short existence of the meanwhile, operators will plan ahead on a networked city scale, to identify soon the potential new sites, share resources and learn from each other.

- Updated catalogue: councils and local groups will need to foster the creation of an extensive, transparent and fast-updating inventory of empty premises susceptible of being ‘meanwhiled’, in close collaboration with landlords.

- Data management and resilience: every functioning meanwhile use will implement a systematic (potentially standardised) data harvesting protocol, in order to learn fast and adapt to changing demands and future realities.

- Collaborative platform: the open and connected nature of our platform will allow the testing of innovative urban proposals outside the rigid constraints of formal planning, in a collective and participatory framework.

- Every node of the network will contribute and have access to a shared live database, constantly updated not only by space operators but also by the users.

VII. An interactive digital platform. Collective mapping and collaboration

We propose the use of two main methodologies to implement our decalogue of acting principles:

- Data mapping: detecting and reacting

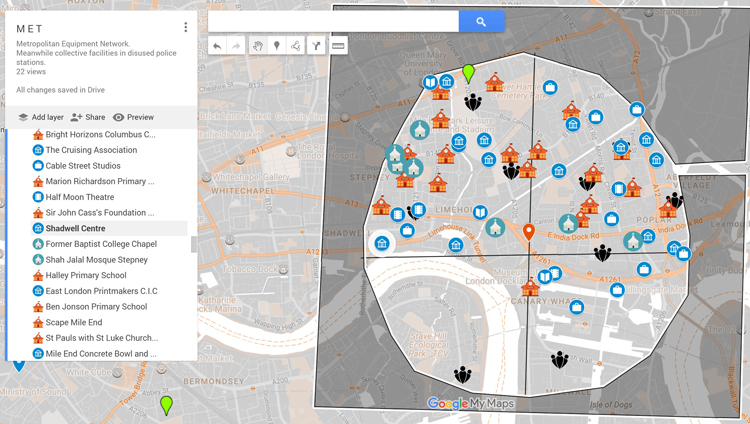

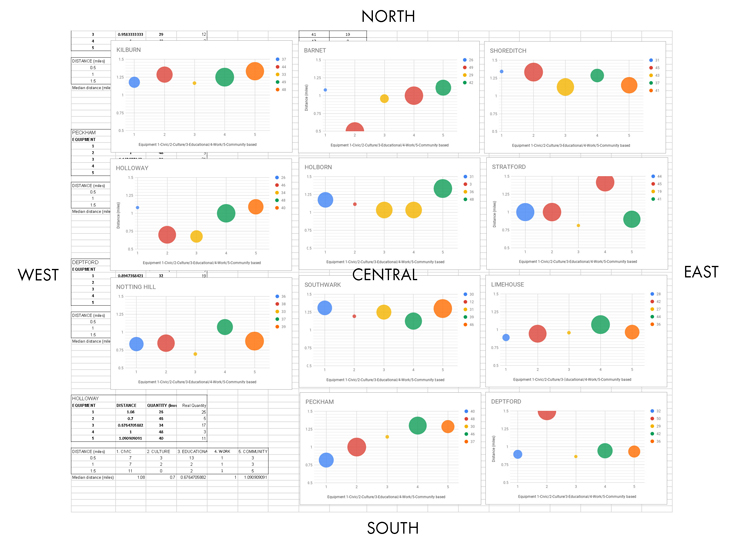

The first approach includes an extensive exercise of mapping, that will allow us to detect and quantify a critical number of areas of study including emptied buildings that match our requirements and neighbourhoods debilitated by redevelopment plans or closure of civic facilities. Likewise our mapping protocol will help us to detect the existing strengths of any endangered communities. This analysis is essential for us to understand thoroughly which temporary programmes are needed, and which ones are redundant to each specific group.

- Using and combining already existing applications such as Google Maps and Free GIS (which are easy to use and accessible to everyone), we started creating our own bespoke protocol to compile and process information on community spaces and empty buildings in different areas of London. As a basis for this we took areas in a radius of 2 miles around abandoned police stations. The goal is to transform all the complex and erratic available information into something easily legible by the public. An in-depth knowledge of the local ‘ecosystem’ will help us understand and interpret the actual needs of the community.

- Collaborative protocols and live feedback for long-term engagement

The second methodology set, based on the data gathered through mapping, consists of a Collaborative Design Protocol for the spatial definition of meanwhile opportunities and their programmes. This protocol includes a series of Live Collaborative Events where initial prototypes will be co-designed and collectively built by neighbours and organisers. It will also be an opportunity to present the results to a broader local audience, becoming an invaluable tool with which to acquire accurate live feedback directly from all the local stakeholders.

Image 8. Analysis of civic deficits and opportunities in the area of influence of 11 vacant police stations. Source: author.

The combination of these two sets of methods constitutes the backbone of our project Meanwhile Community Network, and aims to streamline and accelerate the often inefficient process of definition, consultation and implementation of new public initiatives.

VIII. Making the invisible visible. A collaborative city-built database

The huge property stock of vacant, unoccupied or underused spaces and buildings in London remains mainly unlisted and somehow invisible to citizens. Due to the scale, complexity and dynamic character of the task, creating a centralised inventory of potential meanwhile properties would involve a large investment, unprecedented political will and too lengthy a process to be effective.

Meanwhile Communities Network explores the creation of a participatory digital platform that will automatically generate a live recording of vacant properties with potential to become meanwhile civic spaces. The platform will be continuously fed by the neighbours themselves, who will be able to identify and record any empty buildings they meet during their everyday activities. Users’ input will include key parameters such as building location, original photos, comments, and modified images through a simplified editor embedded in the platform─where they will be able to add filters, text and overlay sketches or maps, thus collectively generating basic ‘reports’. This process will enable neighbours to perform a series of proactive civic functions in an easy and natural way:

- Collective mapping of the area, built up utilising the invaluable knowledge of the locals

- Detecting and exposing spaces with realistic potential for the community, that otherwise would remain unnoticed to the majority

- Validation and quantification of that potential through exchange of information and opinion with neighbours

- Connecting with other neighbours quickly and efficiently to share, discuss or organise campaigns and other community actions

- Define real and specific local needs and convert them into a coherent and sustainable programme of activities to be housed by the meanwhile proposals

As technology allows us to devolve these abilities of local communities, we want citizens to become proto-planners and proto-designers within a simplified, safe and constructive environment. A more integrated and collaborative approach to planning, design and building can soften the roles and boundaries between the stakeholders and neighbours involved in the development of a meanwhile project, opening up the process of urban redevelopment.

Notes

1. Mueller, B. (2019). What is austerity and how has it effected British society?, The New York Times [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/24/world/europe/britain-austerity-may-budget [Accessed 05 May 2021].

2. Alston, P. (2018). Statement on visit to the United Kingdom. London: United Nations, p. 13

3. Locality.org.uk (2018). The Great British Sell Off. [online] Available at: https://locality.org.uk/policy-campaigns/save-our-spaces/the-great-british-sell-off/ [Accessed 05 May 2021].

4. Gelder, S. (2019). Most London police stations closed to public two years ago still haven’t been sold. Hackney Gazette [online]. Available at:

https://www.hackneygazette.co.uk/news/crime/most-london-police-stations-closed-to-public-two-years-ago-3639442 [Accessed 05 May 2021].

5. Bosetti, N. and Colthorpe, T. (2018). Meanwhile, in London: making use of London’s empty spaces [online]. London: Centre for London, p. 8. Available at: https://www.centreforlondon.org/publication/meanwhile-use-london/ [Accessed 05 May 2021].

6. Ibid, p. 26

7. Ibid, p. 4

8. Ibid, p. 36

9. Ibid, p. 47

10. Ibid, p. 45

+

The work presented in this article has been produced as part of an ongoing research study on the concept of ‘Meanwhile’ applied to Community Projects, through various real-life applied projects designed and lead by BARE.

Israel Hurtado Cola is a founding director at BARE Community Design, and lectures in architecture at masters level at London South Bank University. Moving between academia, research and real-life projects with a community focus, he explores innovative ways in which well considered and creative design can dramatically improve our urban lifestyles. Through BARE he has been involved in numerous collaborations with public institutions, private companies and local communities across the UK and internationally, to promote spaces that are more sustainable, engaging and inspiring both socially and environmentally.

Volume 4, no. 2 Summer 2021