Understanding the past, reshaping the future: Creating a space in Oslo’s Linderud Community Garden

– Kimberly Weger and Clara J. Reich

Linderud Gård is a 17th century historical farm and manor, located in the Bjerke district in Oslo, Norway. The estate consists of one of Norway’s best preserved historical gardens, the manor museum, as well as the newly established community garden. It is unique in combining the preservation of the past with a moldable space for the present and future.

After being a closed private space for over 300 years, Linderud farm opened its gates to the community in 2007 as a park managed by the Museum group, Museum in Akershus (MiA). This reopening has been supplemented by the spring 2020 opening of the six-acre northwest field of the farm to the community, through funding from the Horizon 2020 Project Edible Cities Network (EdiCitNet). As part of EdiCitNet, municipal actors, research institutes, and private businesses are collaborating on using an ‘urban living lab’ (ULL) methodology to establish an open and accessible space for innovative urban food production, sustainable business models, and circular resource use. The project aims to empower a diverse group of actors— with a focus on residents with minority backgrounds— to re-imagine how the space is used now and in the future.

With our work at Nabolagshager, we as authors and project partners chose the ULL methodology for this urban transformation as a way to create a physical space that is accessible, open for ongoing collaboration, and enables residents to define the questions and problems that are important in their community. The concept of ULLs has originally been developed within the Smart City context1 based on participatory design principles, with the expectation that key users are actively engaged, creating a sense of ownership and inclusion. As part of creating local identification and participatory engagement, the research for this article was conducted in collaboration with local youth hired and trained by Nabolagshager staff. These youth conducted qualitative interviews and observations during youth-led open community events. Within the ULL methodology it is theorised that engaging in ULLs can strengthen social connections among urban residents, and lead to diffuse societal impacts such as cultural changes towards more educated and engaged citizens2. ULLs are thus understood by proponents as “distinct in terms of their explicit place-based focus and their future-orientation, seeking to experiment today with solutions for the future”3. By having the local youth conduct qualitative research by engaging with members of their own community to discuss the future of this place, we sought to enable this process of experimentation and local engagement to flourish.

The “place” in this context is located in the culturally diverse East of Oslo. Since the 17th century, the eastern part of Oslo developed less than the more affluent parts in the west of the cities due to class inequalities45. First or second-generation immigrants comprise over 50% of the district’s residents, and the area has been identified by the municipal urban renewal program as having the highest percentage of social and economic challenges in Oslo6. These social inequalities, manifested over 200 years, raise questions about how public spaces can contribute to social inclusion and build intergenerational and cross-cultural trust. The Covid-19 pandemic has increased pressure on residents, who often live together as large family units in small apartments, in dense housing blocks. Many residents have access to green space, but these are unimaginative and non-biodiverse spaces consisting mostly of lawn space with an activity structure for children. What they lack is not just outdoor space, but outdoor space which is natural, encourages a diversity of user groups, and invites users to be creative and allows positive social development and behaviours7.

The cooperative member-based vegetable garden at Linderud community garden was driven by local individuals who had been trying to secure use of the site for over three years. However, the opening of the garden was only made possible through the international EdiCitNet project, which facilitated the opening up the space for the community and funding for drainage of the field. The process of re-imagining the space as a community garden was therefore a complex process, involving international and local actors and visions, all of whom feel ownership over the space. This has created a complex set of problems that do not fit within the traditional ‘boxes’ of how an intervention is initiated8. We find that the re-imagination of the site is a patchwork of actors and competing interests which is continually re-imagined. Many of the cooperative vegetable garden members, for example, were initially unsupportive of the idea of a social meeting space on the site. This exposed the potential conflict between actors whose project funding and visions are based on entrepreneurship, innovative rewilding projects, or creating inclusive urban green spaces, versus local residents who are more interested in securing land for growing their own vegetables.

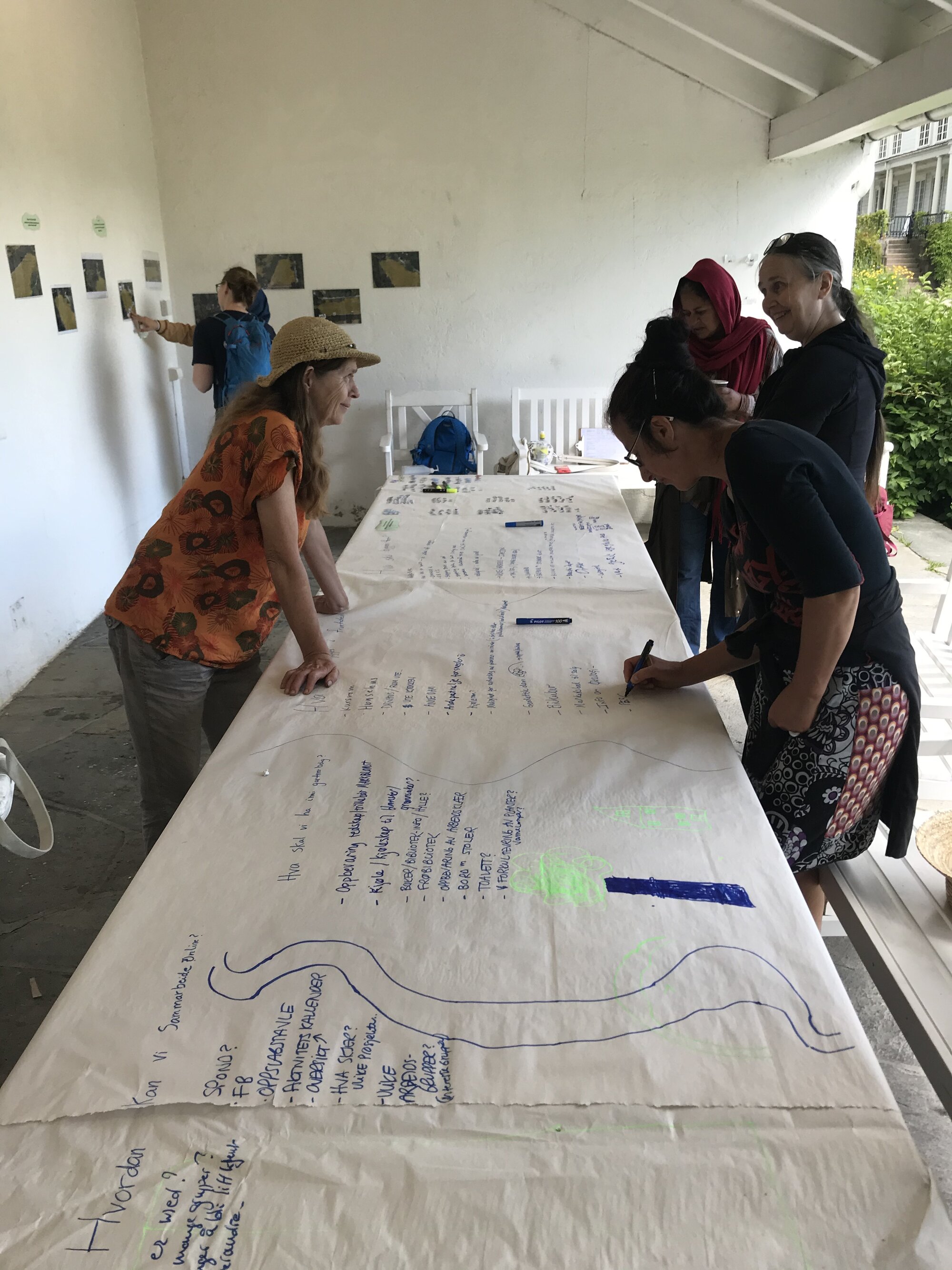

In order to combat these challenges, temporary installations and a slow process of intervening were initiated. Instead of designing outdoor seats and tables for the meeting place, we purchased one hundred organic straw bales which were used throughout the summer as ‘lego’ building blocks to design different forms of seating and structures, while serving as a reminder of the space’s farming past and mitigating conflict because they were understood as temporary and mobile. We built mobile wagons made of recycled materials, one designed as a washing station and one as a product sales table. These were flexible in both use and location, and served to alleviate conflict because they were understood as temporary— local users could determine where and how they wanted to use them, building local ownership over the transformation. We also held free open community events with free food and simple activities for children organized by local youth, encouraging residents to see the value of a natural outdoor social space on the farm. These events attracted people from a wide range of ages and were very popular with residents from immigrant backgrounds, which enabled other stakeholders to re-imagine the space as an inclusive community place. Through experimentation and observations, we found that local children and adults were more likely to engage in simple low-threshold activities— such as throwing a ball at stacked cans or riding a smoothie bike— than more complex organized activities such as scavenger hunts. Through all of these temporary interventions, we invited users to play with forms and reimagine what the space could be— by actively participating and experimenting with the space and its use.

Conclusion

The social inequalities that materialised in the past between different ages and cultural backgrounds in the area became even more visible during the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite living in dense apartment blocks, the natural outdoor space at Linderud farm was perceived as inaccessible to residents from immigrant backgrounds. This inequality revealed the urgency for transitioning this space towards a more accessible and inclusive place for all members of the surrounding community. Despite living close to Linderud farm and having no indoor spaces to meet in during the pandemic, families from immigrant backgrounds were only using these natural outdoor public spaces when invited into the space through organised, simple low-threshold activities for adults and children.

The pandemic has also reinforced the need for flexible urban interventions. Places that can easily be reinvented and invite reinvention according to the changing needs and visions of users at different times. Having urban green space is not enough, rather it is crucial to create activities that invite and justify the use of the place. This is especially relevant for minority groups and youth and may be first met with scepticism by traditional planners, architects and project managers. A just transition must enable competing voices to be heard and for these voices to be able to shape the discussion— for example by engaging youth in observing and identifying needs in the neighbourhoods where they live— while allowing for creative experimentation so that present uses and future visions truly reflect the desires of users. This requires a slow transformation of green spaces using moveable, low threshold, and temporary installations and activities.

Image 5. Youth gathering around the smoothie bikes during an event at Linderud farm. Source: Kimberly Weger.

Notes

1. Hvitsand, C., Richards, B. (2017). Urban Living Lab – Bruk av metoden i Norge og med eksempler fra Europa. ISBN: 978–82-336-0033-4

2. Steen, K., & van Bueren, E. (2017). The Defining Characteristics of Urban Living Labs. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(7):21-33. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1088

3. Voytenko, Y., McCormick, K., Evans, J., & Schwila, G. (2016). Urban living labs for sustainability and low carbon cities in Europe: Towards a research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 123, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.053

4. Andersen, Bengt, and Joar Skrede (2017). “Planning for a sustainable Oslo: the challenge of turning urban theory into practice.”. Local Environment 22 (5):581-594.

5. Myhre, Jan Eivind. (2017). “Østkant og vestkant: Oslos historie som delt by.” Last Modified 04.07.2017, accessed 24.09.2020. https://sosiologen.no/essay/essay/ostkant-og-vestkant-oslos-historie-som-delt-byl.

6. Oslo kommune, (2020). “Oslo Statistikkbanken.” Accessed 10.02.2020. http://statistikkbanken.oslo.kommune.no/webview/

7.Bates, Carolyn R., Amy M. Bohnert, and Dana E. Gerstein. (2018). “Green schoolyards in low-income urban neighborhoods: natural spaces for positive youth development outcomes.” Frontiers in psychology 9: pp. 805.

8. Bulkeley, H. and Coenen, L. and Frantzeskaki, N. and Hartmann, C. and Kronsell, A. and Mai, L. and Marvin, S. and McCormick, K. and van Steenbergen, F. and Voytenko Palgan, Y. (2016). “Urban living labs governing urban sustainability transitions.”, Current opinion in environmental sustainability, 22. pp. 13-17.

Kimberly Weger comes from Canada and received her Masters in Political Science from the University of Calgary, with research on community participation in development in Ghana. After finishing her career as an international athlete in speed skating, Kim worked in Germany in an international sport development project. Kim currently works with the think-and-do tank Nabolagshager on community engagement, with a focus on grassroots and gendered participation.

Clara Julia Reich coordinates an EU project on placemaking and community engagement for Nabolagshager AS in Oslo Norway and collaborates closely with minority youth. She holds a Masters in Development, Environment and Cultural Change from the University of Oslo.

Volume 4, no. 2 Summer 2021