Urban Gating: a Swedish take on the Gated Community

– Karin Grundström

Gates and fences cut through and divide cities. In Paris, a fence is to be constructed around the Eiffel tower and in New York artist Ai Weiwei will comment on the increasing enclavism of societies by building more than 100 fences and installations throughout the city. Worldwide, fences and locks restrict access for the unwanted while wealthy residents dwell in exclusive gated communities. Swedish cities do not have the equivalent of gated communities, in the sense of isolated islands of ‘incarceration’ (Atkinson, 2006) or of a ‘fortress city’ (Low, 2003). However, since the 1990s, Swedish cities have seen a significant increase in the use of locks codes, gates and fences that restrict access to land that was previously publicly accessible (Grundström, 2017). Even though Sweden does not have the equivalent of ‘gated communities’ neither as urban form, nor as defined by the Anglo-American concept, I argue that there is indeed a process of gating. The gating process in Swedish cities, which I refer to as urban gating, is a dispersed form of gated blocks and gated housing complexes, which taken together, result in restriction of public access and a significant change of urban form.

When researching the process of gating in Malmö Sweden, I have explored gating through both image and text, and through linguistic and conceptual definitions. Theoretically my starting point is based in understandings of how physical and social positions in space coincide; how privileged groups keep the unwanted at a distance and simultaneously acquire easy access to exclusive services, amenities and mobility (Bauman, 2000; Bourdieu, 1994; Wacquant, 2007). Methodologically, the research is based on abductive reasoning and imaging and includes interviews, observations, and mapping (Cross, 2011). In the research process, mapping has been an approach through which to explore, identify and define the phenomenon of gating in the Swedish urban context. Mapping and writing have been parallel practices of equal relevance and importance to the conceptualisation of urban gating. The article presents how ideas of gating are materialised depending on morphology (Case Scheer 2010; Moudon 1997) and the consequence of gating on public accessibility and on urban form, presented through a morphological-historical mapping of gating.

Origin and urban form of the gated community

In Swedish media debate and the (very limited) research on gating, the Anglo-American concept ‘gated community’ is imported and referenced to in urban and linguistic contexts. Moving concepts between languages and cultural borders can, no doubt, be constructive and further new thinking, but it may also influence ideas and understandings to the extent that difference and variations are not taken into account, or that they are simply overlooked (Yip, 2013). Importing – or transferring – the concept ‘gated community’ to Sweden poses a challenge since it does not readily translate, neither to the Swedish language, nor to Swedish planning laws or to urban form.

To begin with, the concept of community poses a challenge of translation, since the word community does not exist in the Swedish language. Certainly, groups of people live together and establish feelings of togetherness gemenskap where they live, but individuals are primarily linguistically positioned by where – in what area, street or house – they live and not with whom. Additionally, society rather than community is, politically and culturally, the concept defining the Swedish sense of togetherness, a notion based in a strong bond between the individual and the state (Trägårdh, 2012). Secondly, it is important to note that planning laws and regulations influence possibilities to gate land that is defined as public allmän. According to Swedish planning- and building law, ‘a public place is a street, a road, a park, a square or other area, which according to a detailed plan is aimed for public use’. Places that are not public are blocks where construction is permitted, defined as kvartersmark ‘land which, according to the detailed plan is not a public place or body of water’ (Plan-och Bygglagen, 2010). Importantly, these laws in principle over rules property rights: no matter who owns the land where a street is built, it is public in the sense that people have the right to access and use it. Laws and rights in support of public access thus to a certain degree limit the possibility to construct private neighbourhoods, private streets, or private parks to which public access is prohibited, such as may be the case in Anglo-American gated communities (Atkinson & Blandy, 2006; Blakely & Snyder, 1999; Low, 2003).

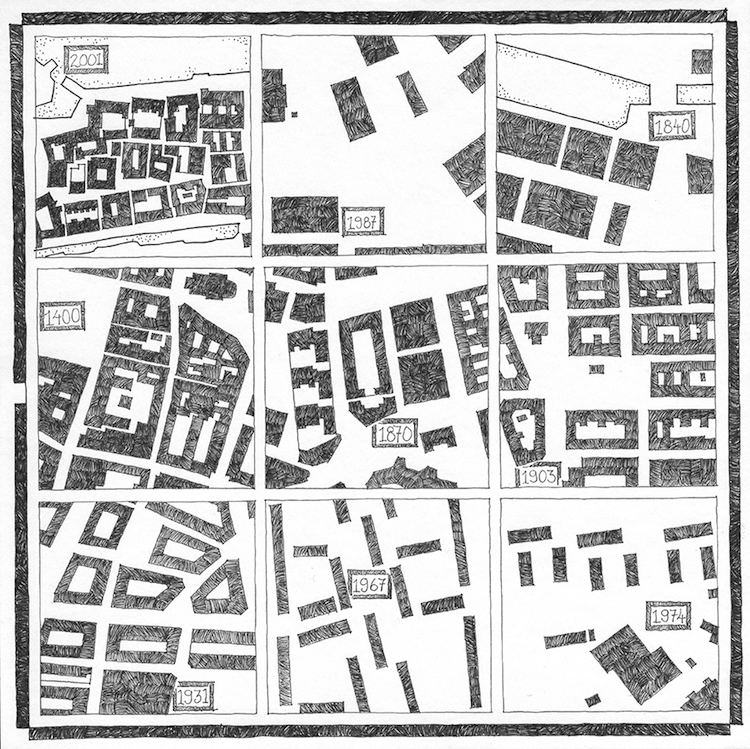

In addition, there is also a crucial difference in urban form between European and U.S. cities, which influence how gating takes shape. In the U.S. context, Blakely and Snyder (1999) define three forms of gated communities; prestige, lifestyle and security zone community. The gated community originates from the luxurious settlements of the wealthy elite who withdraw to mansions in park-like landscapes in order to avoid noisy and polluted cities. One of the first examples was Tuxedo Park, built outside New York in 1885. The gated community was from the beginning an elite form of housing, and it remained so until a drastic increase in the 1970s, when middle class, leisure and retirement homes were built in the Sun Belt. A second increase in the number of gated communities occurred in the 1980s, but at this moment in time, gated developments were also built on fear (Low, 2003). Central to the urban form of the gated community is the ‘loop and lollipop’ settlement pattern of post WWII U.S. urbanism. This layout ensures individual car access to each house and creates buffer zones between and around each housing area. Furthermore, such a housing area has one main entrance to the next level of the street system, which facilitates control of access. Even if grid systems are found in gated communities, the gated community was primarily grounded in a cul-de-sac street system, with one guarded entrance combined with walls or fences surrounding the ‘community’.

1. Karin Grundström, U.S. Gating, 2017. Ink on paper, 32 x 32 cm. Conceptual map of the morphological-historical development of the gated community, showing the loop and lollipop urbanism prevalent in gated communities, and key dates of gated housing development in the U.S.

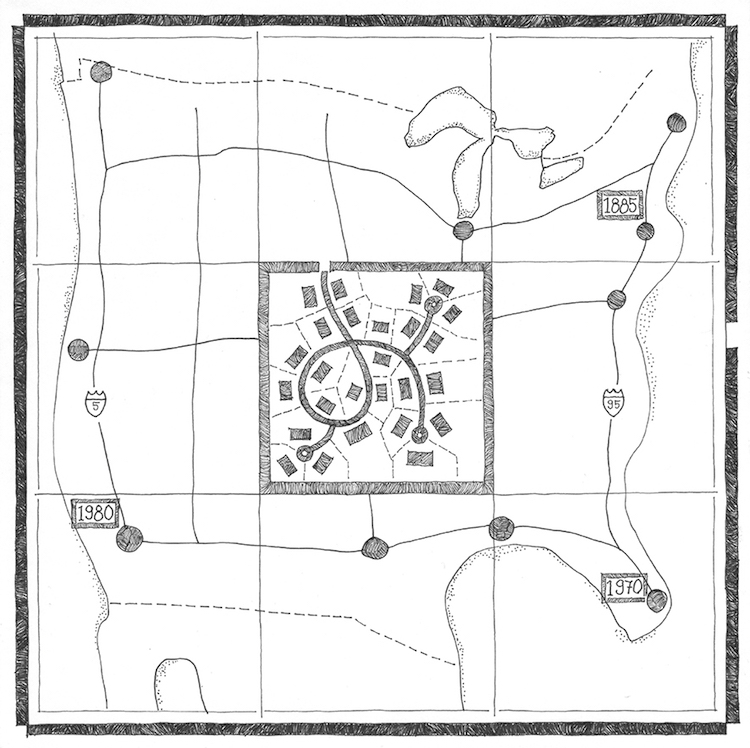

The concept of the gated community has, since the 1980s, travelled the world and is applied in varying cultural and urban contexts (Atkinson & Blandy, 2006; Grant & Middlestedt, 2004; Grundström, 2017; Yip, 2013). One of the cities where it landed is Malmö, the third largest city in Sweden. Malmö was founded during the middle ages and had, by the fourteen hundreds developed into a city. Through the centuries the city grew slowly until the turn of last century when it doubled in size. At the time when the first gated community outside New York was constructed, Malmö planned and built stone-town blocks of housing. A second phase of large expansion occurred during the 1960s -1970s when the country constructed close to one million housing units, this time in a contrasting urban form with freestanding buildings in open landscapes. One of the first debates on gating in Sweden was when a regeneration project, in the 1870s quartier, added locks, gates and fences to the premises in 2001. While gated communities had been increasing rapidly in the U.S. for two decades, the development of fences and gates was deemed ‘unlikely’ in Sweden (Öresjö, 2000).

2. Karin Grundström, Malmö Morphology, 2017. Ink on paper, 32 x 32 cm. Morphological analysis of Malmö based on a section through the entire city from West (upper left) to East (lower right). Buildings are presented in the same scale and dated based on time of original urban development. The map dated 1870 shows the addition of modern, gated housing to the traditional stone town urbanism.

Urban gating

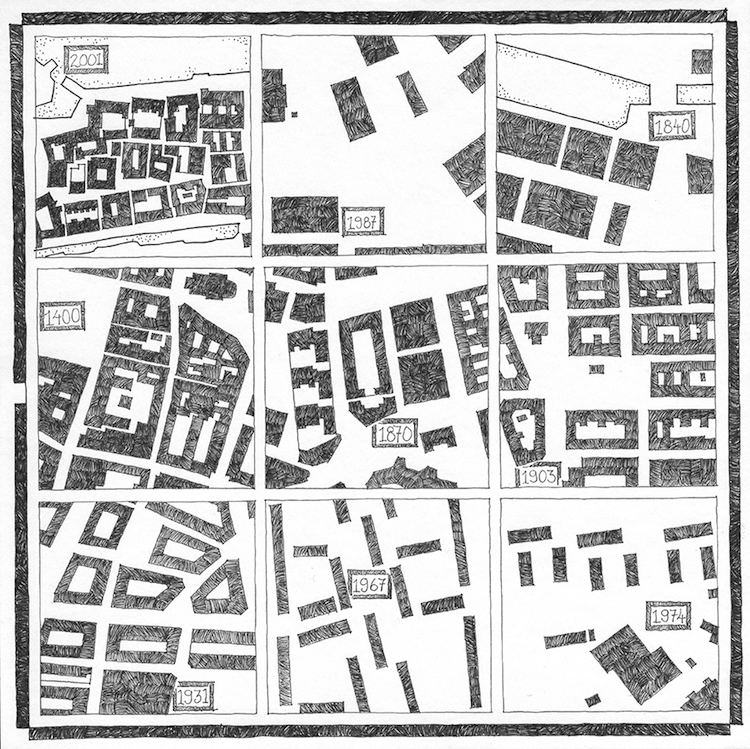

Locks, fences and gates have been constructed along with new forms of exclusive, gated housing as the Swedish metropolitan regions, Stockholm, Göteborg and Malmö, have gone through processes of social and geographical polarisation (Grundström & Molina, 2016). Locks and codes were introduced during the 1990s, while gates, walls and fences started to develop around the turn of the century. Even if gating in Sweden bares reminiscence to the U.S. notion, the urban morphology influences how gating takes shape. Based on the morphological-historical analysis above, three typologies were identified; traditional stone town, which was built until the 1930s; functionalism, which was built between the 1930s and 1980s, and finally, the dense urban block built since the 1980s. In relation to these three typologies, gating is materialised in different ways.

In the traditional stone-town of the inner city, codes and locks efficiently restrict access to courtyards and passages, which are planned and legally defined as public. This may, in an international perspective, seem as a normal condition. However, it should be noted that previous to the 1990s all courtyards and passages were open for public access certifying that anyone could pass through blocks, take short cuts, discover and appropriate (Lefebvre, 2004) the city at his or her own pace and interest. The addition of locks and codes in the traditional stone-town is not entirely obvious to the eye, but never the less, it severely reduces the complexity of the accessible urbanism, from accessibility to courtyards, passages, doorways and streets – to the streets only. In urban districts built during the functionalist era, Corbusier-inspired, freestanding buildings were constructed in park-like environments. In this urban context, fences and gates are clearly visible and severely alter movement patterns since fences and gates surround places originally planned and landscaped as parks and greens accessible to all. This example of gating severely reduces accessibility, but in a visually contrasting way to the previous example. Here, the entire green or landscaped milieu is visible through the fence but not accessible. The consequence is that a substantial amount of land is gated off from public use and that access is reduced to streets only. In exclusive urban districts designed and built during the past two decades, the shape of buildings often includes walls, fences and gates. One example is the dockland flagship harbour development, which was designed based on ideas of the medieval city. Most of the buildings were initially designed with partial walls, but since the inauguration in 2001, smaller additions have been made to gate the housing blocks. In this case, the initial design was not entirely enclosed, but supported the option of easily restricting access. Another example is Victoria Park, a housing complex that spurred a debate about whether or not gated communities do exist in Sweden. According to the developer, the idea behind the project was to import the concept of the gated community to Sweden, by combining apartments with a lounge and reception, a restaurant, spa area and a green, completely gated from public use. The location of the housing complex, next to an old lime quarry turned into a natural preservation area, means that access is easily controlled by the reception and by low fences and gates (Grundström, 2017). Both of these developments are examples of how current design includes material ways of privatising urban land and restricting access.

3. Karin Grundström, Urban Gating in Malmö, 2017. Ink on paper, 32 x 32 cm. Three typologies of gating were identified along a section between East and West in Malmö. The three typologies – dense modern (top); traditional stone-town (middle) and functionalism (low) – are presented in original form (left) and after gating (right). The years on the central map shows the year of gating for the respective typology.

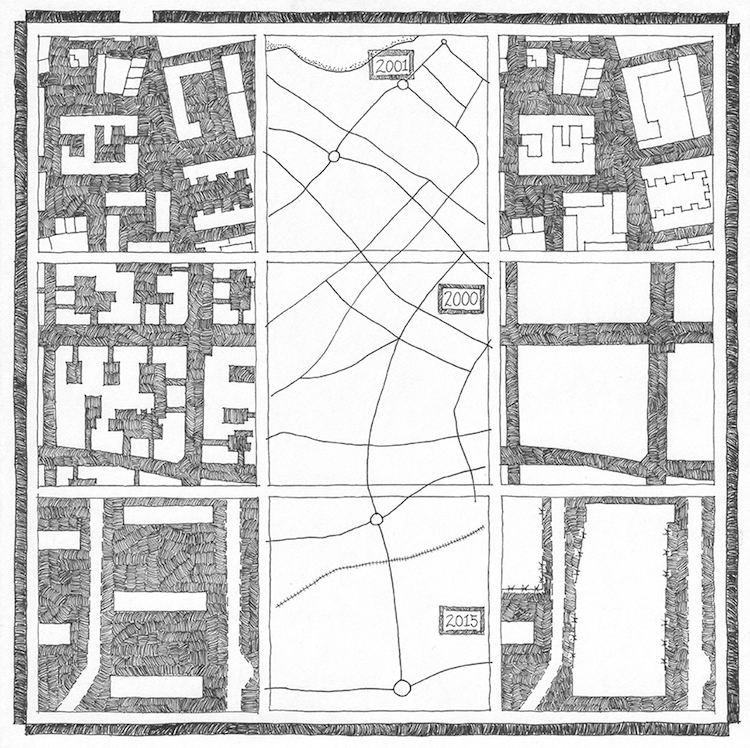

Taken together this results in urban gating, a process of restricted access to urban land – which before the 1990s was accessible to the public – through the increased use of locks, fences, walls, gates and architectural designs. Urban gating is a process through which smaller parcels of land are materially fenced off or gated from public use. It may not be apparent on the individual housing unit or block, and is not as visually apparent as the ‘gated community’, but taken together, and seen from the scale of the urban landscape, it takes the shape of a dispersed form of urban gating.

4. Karin Grundström, Swedish Gating, 2017. Ink on paper, 32 x 32 cm. Conceptual map of urban gating, showing the grid-based street pattern and gating within urban blocks in the Swedish morphological-historical context of 2017.

Conclusion – a Swedish take on the gated community

As shown above, the U.S. gated community is not readily translated to the Swedish urban context, but even so, urban gating does exist in Sweden. Within the field of research on gating, this article makes two contributions. First, by conceptualising urban gating related to a specific urban form. This is important since the meaning of fences and gates vary and the use of the Anglo-American concept risks rendering other notions invisible. The concept urban gating is not equivalent to the US gated community, since it takes shape on an urban scale and not at neighbourhood level. It is a series of gated blocks dispersed through the cityscape rather than a gated, neighbourhood enclave. One result of urban gating is that a considerable amount of land, which was publicly accessible before the 1990s, is gated off from public use. Access is restricted, or denied, to greens, courtyards, passages and in-between spaces of the city and thus the use-value of public urban land allmän platsmark is reduced. Another result of urban gating is a significant change of original morphology, as seen in ‘Urban gating in Malmö’ (map 3, above). Seen through the perspective of the Nolli-plan, the varied and complex morphology is reduced from three typologies to that of one typology only, comprised of the street system and a gated urban block. One may argue that the urban form as such does not change, which is true, but the addition of fences, locks and gates renders the experience of the complex morphology inaccessible to the urbanite. Secondly, the article contributes by suggesting and presenting morphological-historical mapping as an approach to research through both image and text; based on abductive reasoning and imaging. This is important since the field of architectural research is young and new approaches that take both the visual and textual forms of expression of the field into consideration is central for future research.

Research on gating is an evolving field in Sweden. Gating is, as in this article, of relevance to morphology, but it also touches on issues of mobility and public access. One entry point for future research is the definition of– and access to– public and common land. Urban gating can be understood as a decrease of a common resource, of access to greens and common areas at large. Perhaps more important than the right of access to courtyards or green areas as such, is the right to mobility as an urban experience. The experience of freedom of movement, taking short cuts through large blocks, finding unexpected places, calling on friends; having the right to move freely through the entire urban fabric. This way of being able to move through the city, having the right to move while not destroying or disturbing, holds a notion similar to that of the ‘right of public access’ in rural areas, according to which people have the right to move over privately owned land (Naturvårdsverket, 2011). This right, or rather praxis, is today being restricted, and is, in a sense a restriction of the right to use-value of common land (Harvey, 2008). If the gated community in the Anglo-American sense is a reinforcement of private property, the Swedish take is that we are gating our commons. Even though gating has not spread through the entire city, the development is unfortunate since the notion of the urban allmänning comprises the right not to be excluded in a space where use-value overrules property value, which is a notion that ought to be protected.

References

— Atkinson, Rowland & Blandy, Sarah Ed. (2006). Gated Communities. Abingdon: Routledge.

— Bauman, Zygmunt. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

— Blakely, Edward, J. & Snyder, Mary Gail (1999). Fortress America, Gated Communities in the United States. The Brookings Institution Press & Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

— Bourdieu, Pierre (1994). Praktiskt förnuft. Bidrag till en handlingsteori [Raison pratiques. Sur la théorie de l’action]. Göteborg: Bokförlaget Daidalos.

— Cross, Nigel (2011). Design Thinking. London: Bloomsbury.

— Case Scheer, Brenda (2010). The Evolution of Urban Form, typology for planners and architects. Chicago: The American Planning Association.

— Grant Jill & Mittlestedt, Lindsey (2004). Types of Gated Communities, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 2004 Vol 31: 913-930.

— Grundström Karin (2017) Grindsamhälle: the Rise of Urban Gating and Gated Housing in Sweden, Housing Studies. doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1342774

— Grundström, Karin, and Irene Molina. (2016). From Folkhem to Lifestyle Housing in Sweden: Segregation and Urban Form, 1930s–2010s. International Journal of Housing Policy 16 (3): 316-336. doi:10.1080/14616718.2015.1122695.

— Harvey, David (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review 53:2008, 23-40.

— Lefebvre, Henri. (2004). Rhythmanalysis, space, time and everyday life [Originally published as Éléments de rhythmanalyse, 1992]. London: Continuum.

— Low, Setha (2003). Behind the Gates, Life Security and the Pursuit of Happiness in Fortress America. New York & London: Routledge.

— Moudon, Anne Vernez. (1997). Urban morphology as an emerging interdisciplinary field. Urban Morphology, no 1: 3-10.

— Naturvårdsverket (2011). Allemansrätten [Right of public access]. Stockholm: Naturvårdsverket. [Online] Accessed at: http://www.naturvardsverket.se/Documents/publikationer6400/978-91-620-8522-3.pdf?pid=4204.[June 2017].

— Plan-och bygglagen (2010) [Swedish Planning and Building Law] 2010:900, §4. Rättsnätet [Online] Accessed at: http://www.notisum.se/rnp/sls/lag/20100900.htm. [May 2014].

— Trägårdh, Lars (2012). Nordic modernity. Social trust and radical individualism. In (Eds.) Kjeldsen, Kjell, Rank Schelde, Jeanne, Asgaard Andersen Michael & Juul-Holm, Michael. New Nordic – Architecture and Identity. Denmark: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art.

— Wacquant, Loïc (2007). Territorial Stigmatization in the Age of Advanced Marginality. Thesis Eleven 91: 66-77, Sage Publications.

— Yip, Ngai Ming (2013). Walled Without Gates: Gated Communities in Shanghai, Urban Geography 33:2, 221-236, Routledge.

— Öresjö, Eva (2000). Låt oss slippa Grindsamhällen! Om social tillit i ett hållbart samhälle [Save us from Gated Communities! Reflections on Social Trust in a Sustainable Society], in (ed.) Nyström Louise, Stadsdelens Vardagsrum, Stadsmiljörådet, Karlskrona: Boverket.

+

This work was supported by the Swedish research council FORMAS under grant number [2010-1043 and 2013-1794].

Karin Grundström is a senior lecturer in architecture and built environment at Urban studies, Malmö University, Sweden. Her research has focused on both the dominant organisation of space and place, as well as people’s everyday resistance and experience of the city. Grundström was educated at Lund University and is a chartered architect. She has published in areas of urban design and planning, housing and segregation and has curated and participated in exhibitions on urban research.

Volume 1, no. 2 Summer 2017