Affective Infrastructures of Knowledge Co-Production

Catalina Ortiz, Yael Padan, Belen Desmaison, Vanesa Castan Broto, Teddy Kisembo, Judith Mbabazi, Paul Mukwaya, Hafisa Namuli, Shuaib Lwasa and Jane Rendell

The notion of affective infrastructures, in the context of knowledge co-production, refers to the unspoken relations that sustain trajectories of joint research endeavours 1. The ongoing dialogue between sociological theories of affect and postcolonial analyses of urban infrastructures has generated interest in material-communication exchanges that escape or exceed language-based communication 2. Affect refers to the relations between bodies and things that exceed narrative description and that concatenate feelings and experiences 3. Sara Ahmed defines affect as ‘what sticks, or what sustains or preserves the connections between ideas, values, and objects,’ central to the daily drama of contingency 4. Affect is thus also central to the socio-material assemblages that sustain urban life, what we refer to as infrastructure.

The focus on affect emphasises infrastructures’ capacity to mediate boundless possibilities 5. In unstable urban contexts, relationships between people and infrastructures are dynamic and constantly reimagined 6. Drawing on experiences from African cities, PK Guma argues that infrastructures are emergent, shifting and incomplete. Like urban affects, infrastructures are contingent and create possibilities amid uncertainty 7. Affective infrastructures allow knowledge co-producers, those who work together to develop shared knowledge, to develop contingent human relations to navigate shared vulnerabilities.

Co-production processes are central to affective infrastructures that do not yet entirely exist and still propel the imagination into alternative urban futures. Three examples of affective infrastructures in Yangon, Kampala and Lima outline the potential possibilities opened up through the co-production of urban knowledge and its materialisation in urban environments: affective infrastructures support building trust and solidarity, facilitate co-learning and enable care.

The examples reveal and create ‘relational configurations’ constituting practices of co-production as yet uncodified in academic and professional methodologies. As figurations that take verbal-visual forms and dissolve the distance between subjects and objects, we might call these, following Donna Haraway, and Rosi Braidotti, ‘feminist figurations,’ 8 especially when they seek ‘the expression of one’s specific positioning in space and time.’ 9 We can think too of how relations of trust, solidarity, care, learning, love and respect can co-figure affective infrastructures which combine visual materials – drawings, diagrams and photographs, and written texts – captions, memories and stories. And in situations of high risk, visual practices – for example the transformation of a photograph into a drawing – can be used to protect vulnerable groups.

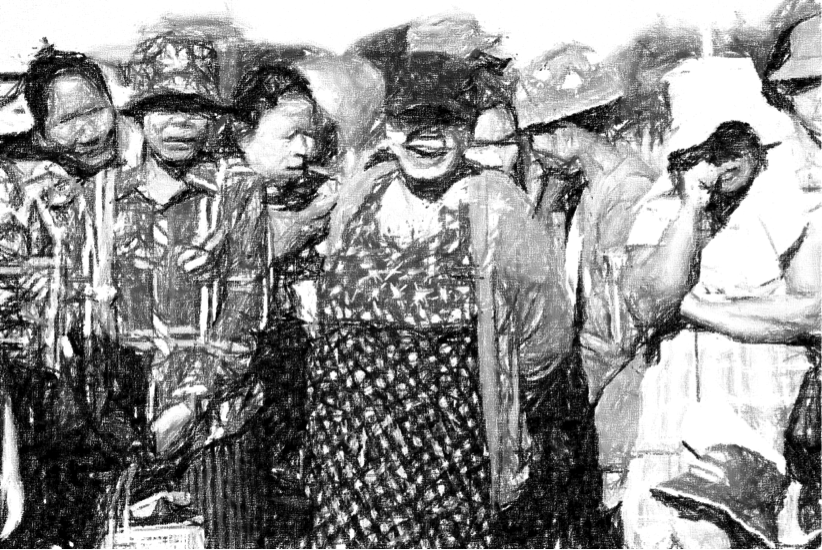

We use this technique to illustrate some moments in the collaborative research we undertook with one of our partners in Myanmar, an NGO called ‘Women for the World.’ We were only able to collaborate on research in this way after over a decade of joint activities through a previous partnership between The Bartlett Development Planning Unit (DPU) and the Asian Coalition of Housing Rights. Prior to any commitment to undertake research together, we worked together through a pedagogical perspective for over three years around a shared interest in community-led housing processes. This process was inscribed in the fieldwork of the MSc on Building and Urban Design in Development at the DPU where ‘Women for the World’ members opened access to community members, local authorities and to academic staff and students. The collective work revolved around the co-design of neighbourhood upgrading in one of the NGO’s key sites. The images depict moments in our encounters that highlight the importance of everyday life in collaborative research practice and knowledge co-production, such as the shared joy of a meal or dancing together.

Infrastructures of trust in Yangon

Infrastructures of trust and solidarity refer to invisible work that enables effective and affective knowledge co-production. In the case of Myanmar, a context where civil rights are severely curtailed given the military regime, promoting spaces of togetherness defies fear and becomes a nonconfrontational resistance tactic among marginalised communities.

Trust is a precondition for engaging in co-production processes. For ‘Women of the World’, the cultivation of trust requires patience and decisive commitment to demonstrate that creating a women-led community housing network is a collective imperative.

Trust lies in the assumptions of goodwill and transparency despite differences in expectations 10. In the process of learning together how to deliver community-led housing, the trajectories of the women’s grassroots network and the local NGO differ but their co-responsibility in the process remains at the centre.

Trust involves a process of building a common understanding within a community of practice. The co-production of knowledge departs from making sense of the shared challenge and agency to transform the material and symbolic conditions of the collective.

Trust is something you build and earn reciprocally through repeated encounters in which the mundanities of life are shared and not only the subject of research. Collective joy is central to enduring relationships based on trust.

Infrastructures of trust are built over time and rely on both personal and institutional connections.

Infrastructures of trust allow the stitching together of relations that need to be nurtured before, during, and after any knowledge co-production process. The affective relations of the joint work became crucial to navigating the co-existing crises of the pandemic, the new military coup, and the climate emergency.

Infrastructures of co-learning in Kampala 11

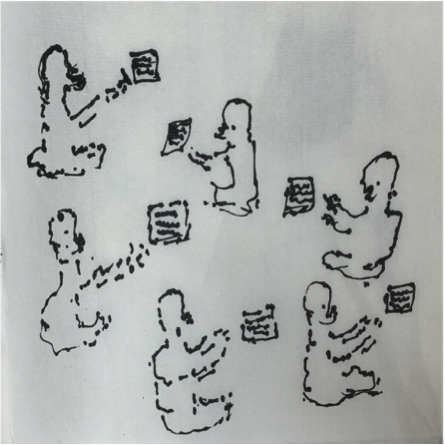

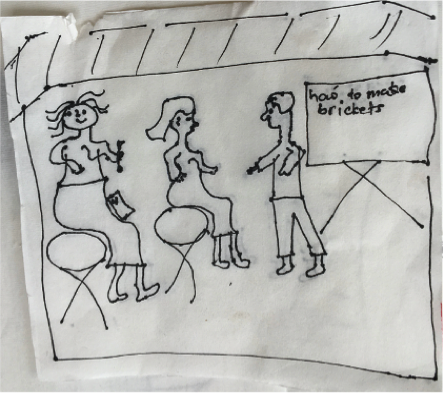

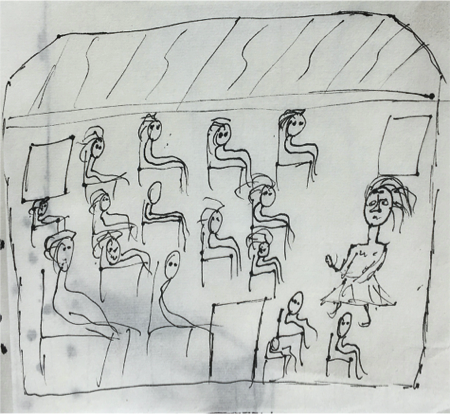

These drawings were made by women members of three community groups in Kampala that produce fuel briquettes from organic waste. The drawings represent processes of learning, co-learning and knowledge sharing between groups.

The KNOW Kampala team, part of the Urban Action Lab at Makerere University has been developing strategies for the transformation of waste management in the city. They have provided extensive training for groups of briquette producers, focusing on improving the production process, scaling up community business enterprises, and integrating them into the urban economy. They are also facilitating the creation of spaces of co-learning, bringing together individuals and groups of briquette producers, as well as groups interested in starting up similar enterprises. By involving other key stakeholders, included policy makers at scale, the team can co-investigate the varying and vested interests in the energy briquette value chain, and to identify capacity gaps and needs in the briquette business. The use of communal spaces allows for interaction, experience and knowledge sharing amongst the stakeholders involved, generating both social and economic benefits.

In one workshop, while drawing, the women discussed co-learning as an affective process. Speaking about the Urban Action Lab team, women from one group said: ‘We learn things from the university. They advise us how to improve the quality of the product. They have loved us, they help and encourage. They give us council about marketing. We feel happy.’

Members of another group used similar words: ‘We are so happy; we are feeling blessed.’ In reference to co-learning, one of the women said: ‘We learned this in a seminar in which we participated together with other groups, organised by the university.’ Another women added: ‘It’s all about having good friends.’ The women’s own words and drawings describe their experience of the briquette-making; while photographs taken by others highlight important moments of the process…

The Bwaise III Kyosimba Onanya group draw.

Women from the Kawaala Kasubi group discuss their drawings.

The Dalaa Ku Dalaa group make briquettes.

Kasubi women briquette group share knowledge.

During the project, capacity building and co-learning have led to significant improvements along the waste-energy briquette value chain. Furthermore, briquette-making is viewed as a catalyst for community mobilisation, social equity, democratic participation, leadership development and an inclusive business model. Across the city, these groups provide infrastructures of care and trust amongst their members, nurtured and sustained through the sharing of common interests, challenges, lived experiences and hopes.

Infrastructures of care in Lima 12

In Lima, COVID-19 has generated a need for infrastructures of care. Community Kitchens popped up in available spaces, often without access to basic services. The kitchens fostered collective discussions to identify potentialities, necessities, and limiting factors for the acknowledgement and sustainability of the community kitchens beyond the current crisis. Participants included the women leading the kitchens, leaders and residents, research assistants from KNOW-Lima and members of CENCA. Discussions on ‘care’ led to a multidimensional understanding of the concept: care for the individual body (proper nutrition), care for the community (diversification of activities), and care for the environment.

Drawings made by community members of the neighbourhood of Santa Rosita in San Juan de Lurigancho in 2020 during participatory workshops, were complemented with virtual exchanges (messaging and calls).These workshops allowed the design of different components necessary for the community kitchens (shelter, storage, cooking, sanitation) and also delineated the roles and responsabilities of each member for the implementation and maintenance of the kitchens.

This architectural drawing shows the components implemented in a community kitchen with bathrooms and water facilities for washing pots and dishes. This proposal includes a phytodepuration plant to recycle waste water for the irrigation of plants to be later used for cooking. It also integrates the public stairs that connect the community kitchen with its surroundings, transforming them into meeting and social spaces.

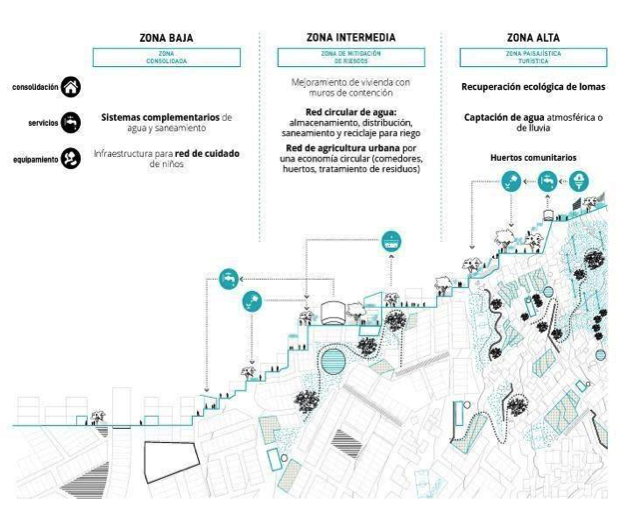

By working on small scale components, the team thought about the replicability of the project, both materially and methodologically. But the KNOW-Lima Team also produced a series of diagrams portraying the multi-scalarity of the infrastructures of care and how they should be articulated in broader social and physical urban systems to promote their sustainability over time.

This diagram for example portrays a future vision of the community kitchens as part of a wider urban infrastructure care, specifically designed for the settlements on the hilly peripheries of Lima. This system expands understandings of care beyond the preparation of meals by incorporating other dimensions of social care like nurseries and study centres, as well as environmental care, by inserting other components of the food cycle such as food production (urban gardens) and waste disposal and recycling (compost).

Care and affection are demonstrated by an active involvement in the implementation process by community members.

These examples of the materialisation of a collective vision towards a better future further construct infrastructures of care. The co-production process included agreements on how the physical infrastructure was going to be cared after by members of the community.

Conclusion

The title ‘Affective Infrastructures’ adopts and adapts cultural theorist Raymond Williams’ term ‘structures of feeling,’ through which he indicated how pre-emergent ‘changes of presence,’ without requiring definition, classification, or rationalization, exerted palpable pressures and limits on experience and on action, and in so doing constituted the social 13. In this article, we move from Williams’ literary concerns with affect, to reflect on the experiences of people and how their actions mediate such changes of presence. More recently affect theorists have warned against subsuming ‘the emergent and fluid states of affective presence’ under more conventional and tangible cultural expressions, 14 placing emphasis instead on methods that respond to and communicate affects, directing attention to the ‘relational configurations of the affects that reverberate in our surroundings.’ 15 In this article, we communicate the ‘relational configurations’ of affects through verbal-visual figurations, and is so doing, hope to show how affect operates in socio-material assemblages through representational and performative forms.

We see these affective infrastructures as central to the construction of urban futures that address multiple visions and understandings of the city, whether through the provision of mutual support through trust, the construction of spaces of co-learning, the development of shared opportunities, and the building of social, environmental and architectural systems of care. These affective infrastructures orient people and communities towards collective goals and sharing urban commons, following efforts to deliver solidarity and trust, co-learn together, and support collective attempts at delivering care. Affective infrastructures redefine ‘infrastructure’ away from hegemonic notions of centralised, networked, efficient infrastructures. They reimagine the city in a provisional, makeshift way, that makes space for initiatives led and delivered by urban dwellers. Affective infrastructures re-conceptualise the urban dweller from a passive receiver of urban services to an active maker of urban futures. The creative efforts through which urban dwellers construct new urban affects are central to challenge the structural and institutional forms of discrimination that they face routinely in increasingly racialised and gendered cities.

Notes

1. https://www.urban-know.com/

2. Moyano Ariza, S. (2020) Affect theory with literature and art: between and beyond representation. Athenea Digital 20(2): e2319, pp. 1-24.

3. Knox, H. (2017) Affective infrastructures and the political imagination. Public Culture, 29(2): pp. 363-384.

4. Ahmed, S. (2004). The Cultural Politics of Emotion. New York: Routledge.

5. De Boeck, F. (2014). The sacred and the city: Modernity, religion, and the urban form in Central Africa. A Companion to the Anthropology of Religion, pp. 528-48, p. 40.

6. Castan Broto, V. (2019). Urban energy landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

7. Guma, PK. (2020). Incompleteness of urban infrastructures in transition: Scenarios from the mobile age in Nairobi. Social Studies of Science, 50( 5), pp. 728-50, p. 729.

8. See Braidotti, R. (2006). Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2006, p. 90. See also Haraway,D. ([2000] 2004). ‘Cyborgs, Coyotes and Dogs: A Kinship of Feminist Figurations and There are always more things going on than you thought! Methodologies as Thinking Technologies: An interview with Donna Haraway conducted in two parts by Nina Lykke, Randi Markussen, and Finn Olesen.’ In Donna Haraway, The Donna Haraway Reader, London: Routledge, pp. 321–42 and Braidotti, R. (1994). Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory, New York: Colombia University Press.

9. See Rendell, J. (2017). Figurations. The Architecture of Psychoanalysis, London: IB Tauris, pp. 210-22. For a book structured of configurations see also Rendell, J. (2010). Site-Writing: The Architecture of Art Criticism, London: IB Tauris.

10. Guillemin, M. et. al. (2016). ‘Doing Trust’: How Researchers conceptualize and enact Trust in their Research Practice, Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 11(4), pp. 370-81.

11. Along with the Kawaala Kasuubi women briquettes group, the Bwaise III Kyosimba Onanya group, and the Kawaala Masanafu Women in Development Agency (MWODEA), the KNOW-Kampala team has included Teddy Kisembo, Thandi Loewenson, Shuaib Lwasa, Judith Mbabazi, Paul Mukwaya, Hafisa Namuli, Yael Padan, Jane Rendell.

12. KNOW-Lima comprises: Lia Alarcón, Paola Córdova, Belen Desmaison, Luciana Gallardo, Kelly Jaime, Luis Rodríguez, Pablo Vega Centeno; and CENCA: Esther Álvarez, Juan Carlos Calizaya, Carlos Escalante, Davis Morante, and Abilia Ramos.

13. Williams, R. (1977). Marxism and Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 131-2.

14. Sharma, D. and Tygstrup, F. eds, (2015). Structures of Feeling: Affectivity and the Study of Culture (v. 5). Walter de Gruyter, p. 6.

15. ibid. p. 6.

+

Image credits Yangon: Catalina Ortiz, Marina Kolovou Kouri, ‘Women for the World’ archive and DPU BUDD archive. Image credits Kampala: KN Image Credits: Images include drawings made by members of briquette producing groups: Kawaala Kasuubi women briquettes group, Bwaise III Kyosimba Onanya group, and Kawaala Masanafu Women in Development Agency (MWODEA), as part of three drawing workshops conceived and facilitated by Thandi Loewenson with Yael Padan and members of the KNOW-Kampala team: Teddy Kisembo, Judith Mbabazi, and Hafisa Namuli, held as part of an event hosted and led by the Urban Action Lab at Makerere University In November 2019, and photographs by David Heymann, Yael Padan and Teddy Kisembo. Image credits Lima: KNOW-Lima Team. Free, prior and informed consent has been given for the use of all the images included here.

Volume 5, no. 2 Jun-Dec 2022