Francesca’s Place: A Topography of Affects, Cities, Mountains and Earthquakes

Federico De Matteis

Francesca’s Place is a phenomenographical account, performed through drawings and photographs, of five central Italian towns, struck by several earthquakes between 2009 and 2017. By describing these places twelve years after the first disastrous telluric event, we try to bring to life the corporeal sensations experienced during our exploration, in an attempt to uncover a deeper stratum of knowledge, remaining otherwise opaque to conventional methods of representation. Such knowledge, we argue, can prove useful when imagining the reconstruction efforts in this and other post-catastrophe settings.

- “That night, twelve years ago, Francesca was there. She ran from the house into the street while the earth was still trembling. Under the floodlights, in the tumult of the rescuers’ frenetic digging, she saw bodies lifted from the rubble. Today, houses again rise where there had been ruins, but Francesca’s place has changed. When she walks through the streets, among the reopened shops and the myriad of building sites, her body feels displaced. There are some parts of town where she no longer likes to go, and she often finds herself spinning in concentric circles around the areas that have not yet been rebuilt. There is one building in particular from which she stays away: a friend used to live there, and the structure still stands, albeit warped, deformed, as if kneeling rather than standing. Occasionally, she holds her breath and walks through the deserted streets to that house. As she stands in front of it, something stirs from her stomach upwards to the base of her throat, and her back muscles contract: she feels cold, even in summer. She looks away. Sometimes, while in the evening dim of the main street, or in the large square, looking onto the mountains, or even in bed drifting towards sleep, she suddenly feels that stirring rise out of nowhere. In the night’s darkness, the gaping building displays – unseen – what once was its private, inner life. Francesca’s place has changed.”

Francesca is a fictional character, summarizing the affective afterlives of thousands of people who have experienced the sequence of earthquakes that has struck the Italian Apennine mountains over the last decade: L’Aquila 2009, Emilia 2012, Central Italy 2016-2017. Some historic towns have been entirely shattered and lie abandoned; others, severely damaged, are being laboriously rebuilt. Beyond these differences, the trauma persists in the inhabitants’ corporeal disposition. The way they sense their cities’ spaces and homes’ comfort has changed. A house that collapses onto its inhabitants is no longer a shelter: it becomes a threat. A city turning into a landscape of destruction stops serving the purpose of harboring public life: trust is severed. Even for those who were not first-person witnesses of the event, the trauma appears embedded in the buildings, in the inhabitants’ postures and gestures, in the atmosphere of the towns and in the landscape. Such traces, the symptoms of the trauma, are due to remain in place for a long time, as a constituent part of the cities’ human space.

Colossal reconstruction efforts are slowly reinstating much of what once was, in the exact forms of its previous life. The political will is for these cities to rise again, more beautiful than before: but the naïve anastylosis remains blind to the trauma toning the inhabitants’ life. A newly reconstructed building coated with fresh plaster may be identical to what was shattered by the earthquake, but it altogether modifies the human space winding through the architectural objects, the streets and squares, merging them with the inhabitants’ corporeal sensations. As architects, we often focus on built objects, on the materiality of things and their making: but to help heal the trauma, we must look beyond the physical dimension, to that universe of acting forces that inhabit space but can be hardly seen or touched. Architecture affects us, articulating our sense of presence: how does this affect change when our houses and cities have turned upon us, making us fear the walls that should create our shelter?

Francesca’s Place intends to address this question. In recent years, I have been exploring the issue of the destruction caused by seismic events and the ensuing reconstruction through the lens of the inhabitants’ corporeal response to the dramatically modified urban spaces. The lived body, in my understanding, is a soundboard of experience, spontaneously resonating with the qualities and agents we encounter in the environment. It is a primary, non-verbal form of cognition speaking the language of emotions: as such, we have difficulty in pinning it down, articulating it in transmissible forms serving as the foundation of design. To do so, it is necessary to develop phenomenographical tools capable of merging conventional architectural description with forms of notation that are tonal, synesthetic, metaphoric. The goal is not to produce a representation of the traumatized cities’ urban spaces, rather to make present the direct, first-person experience of this reality.

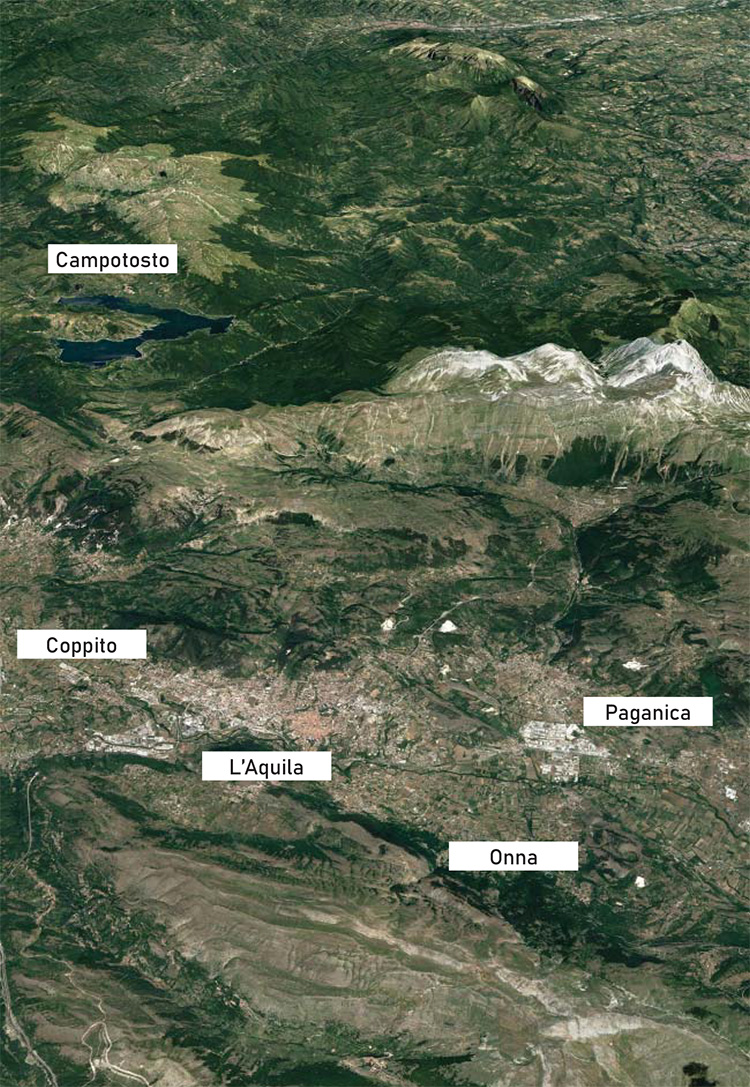

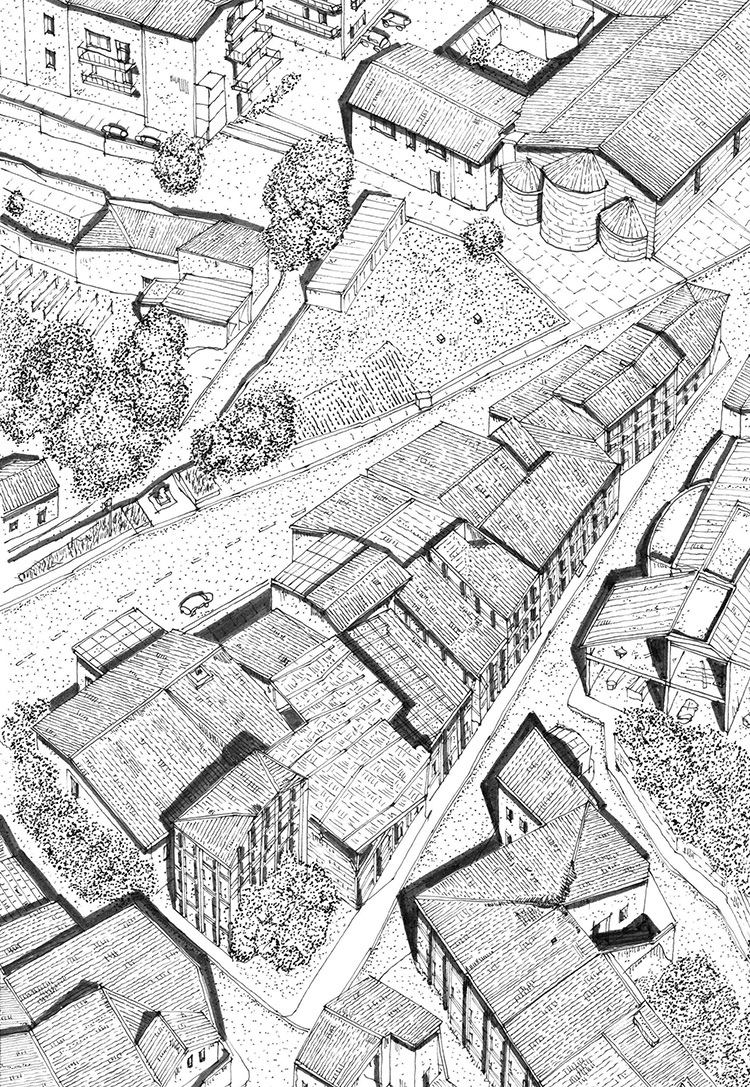

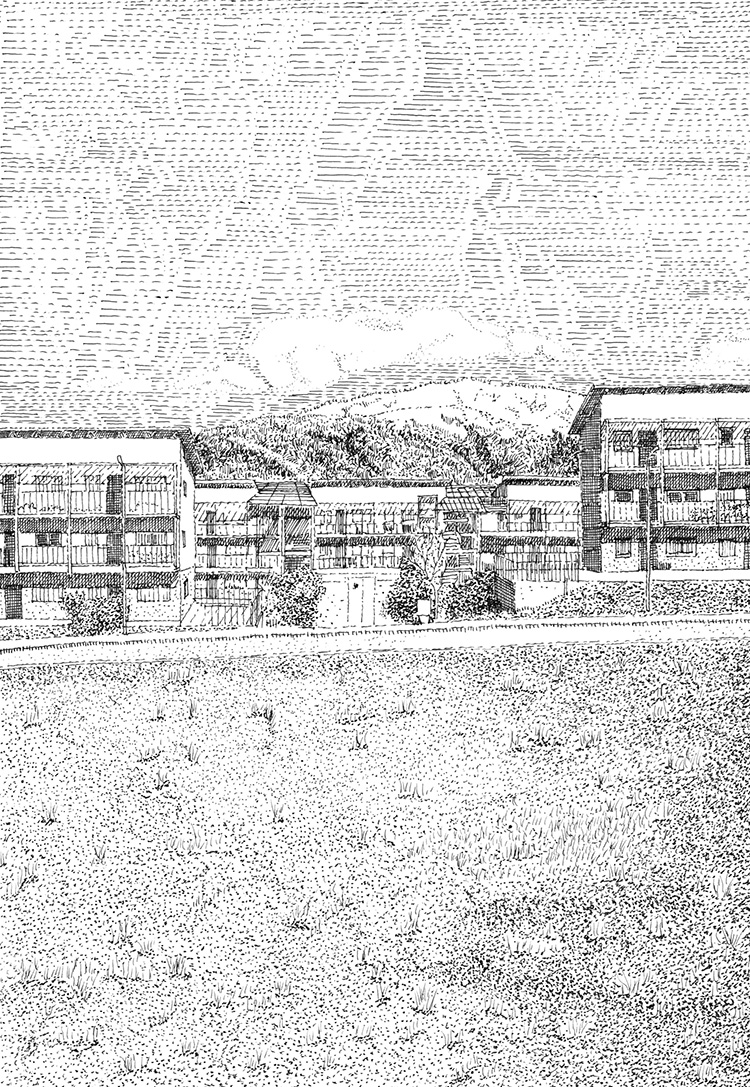

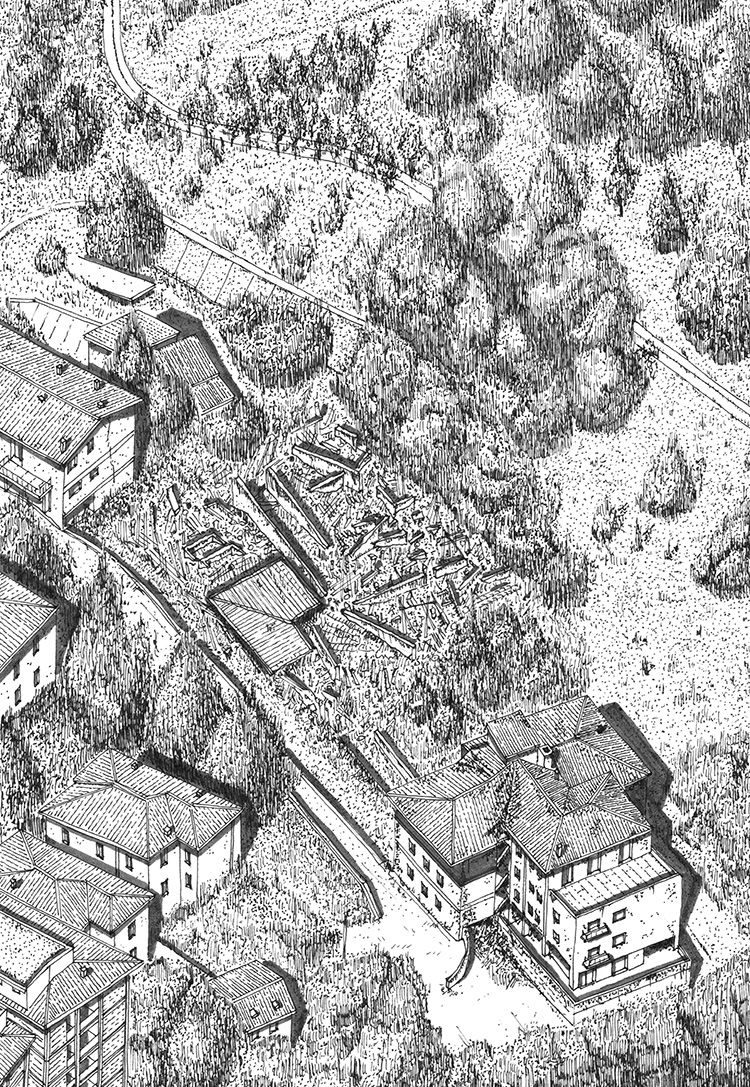

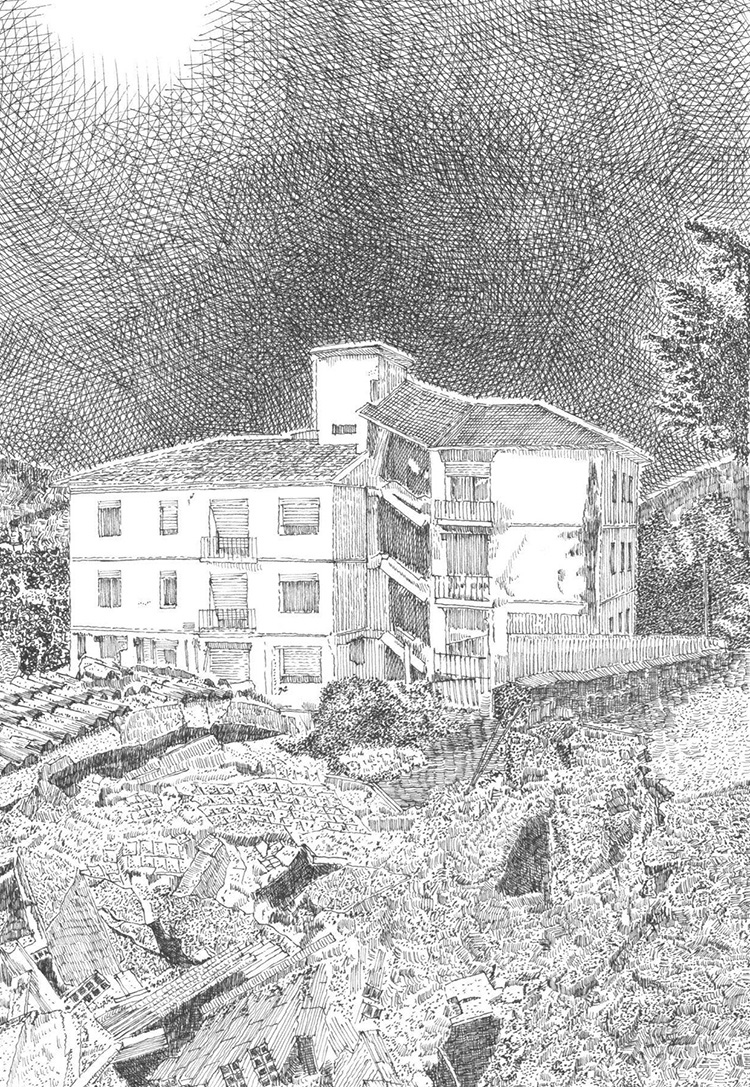

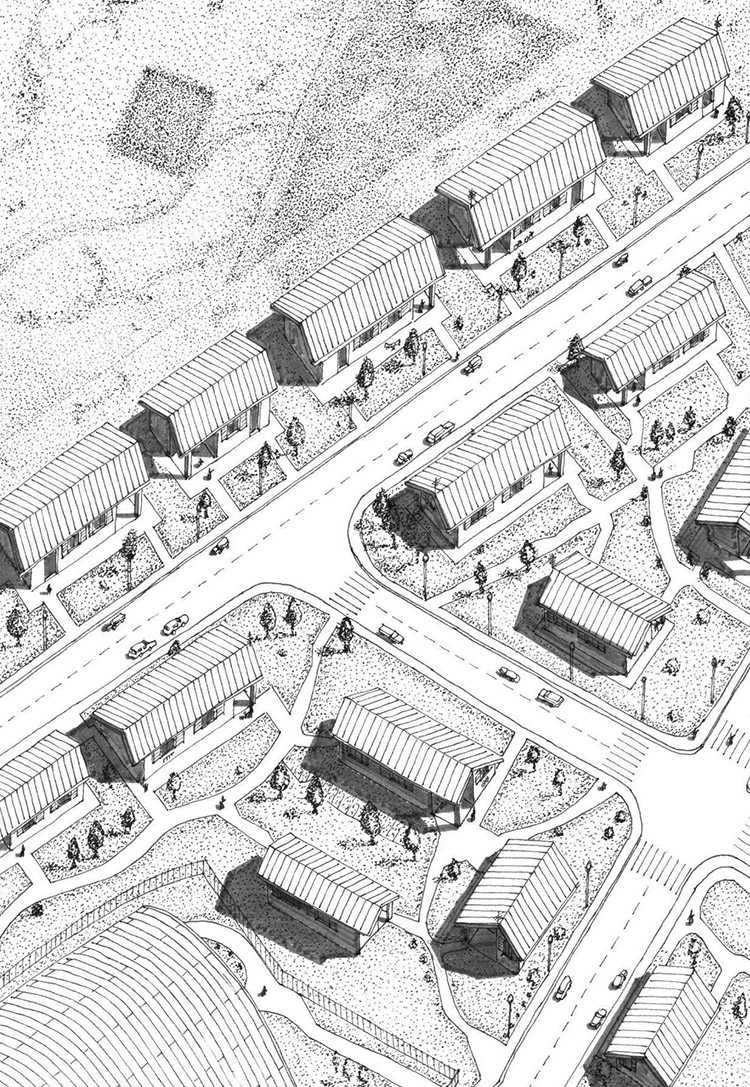

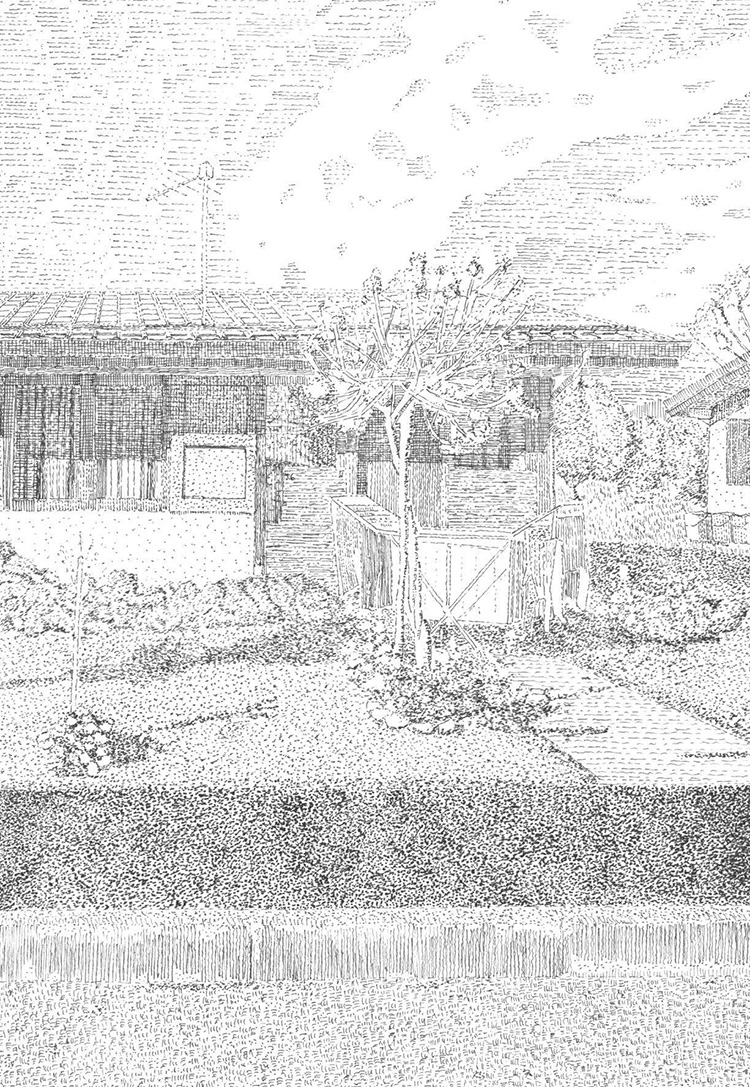

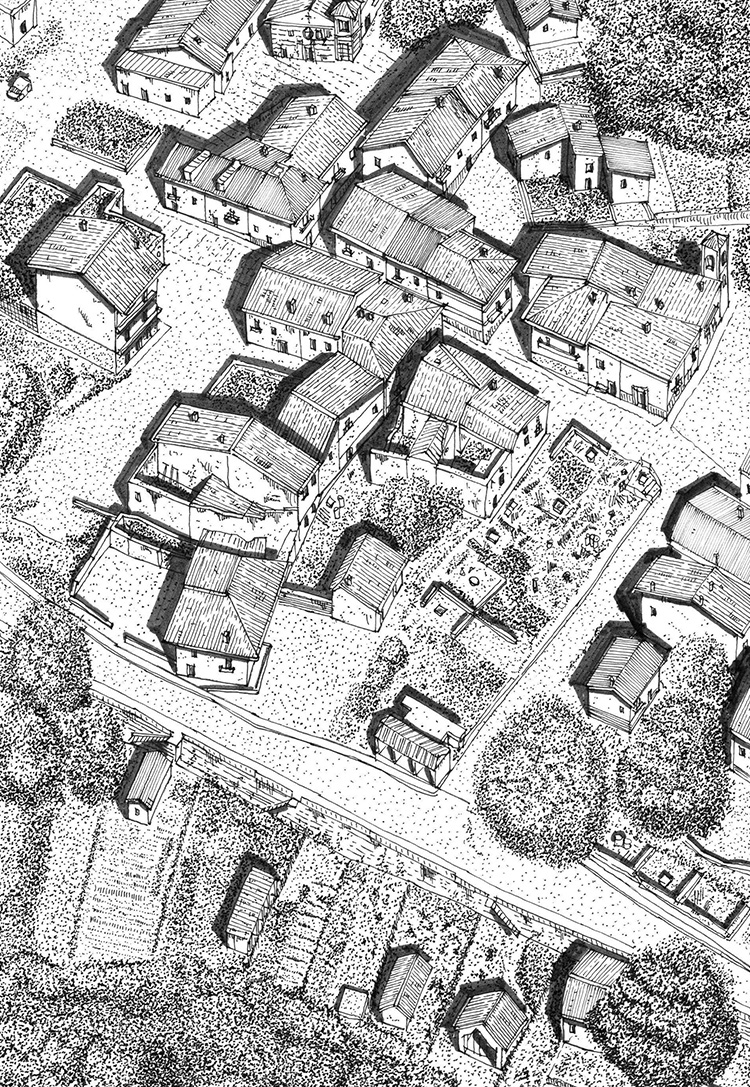

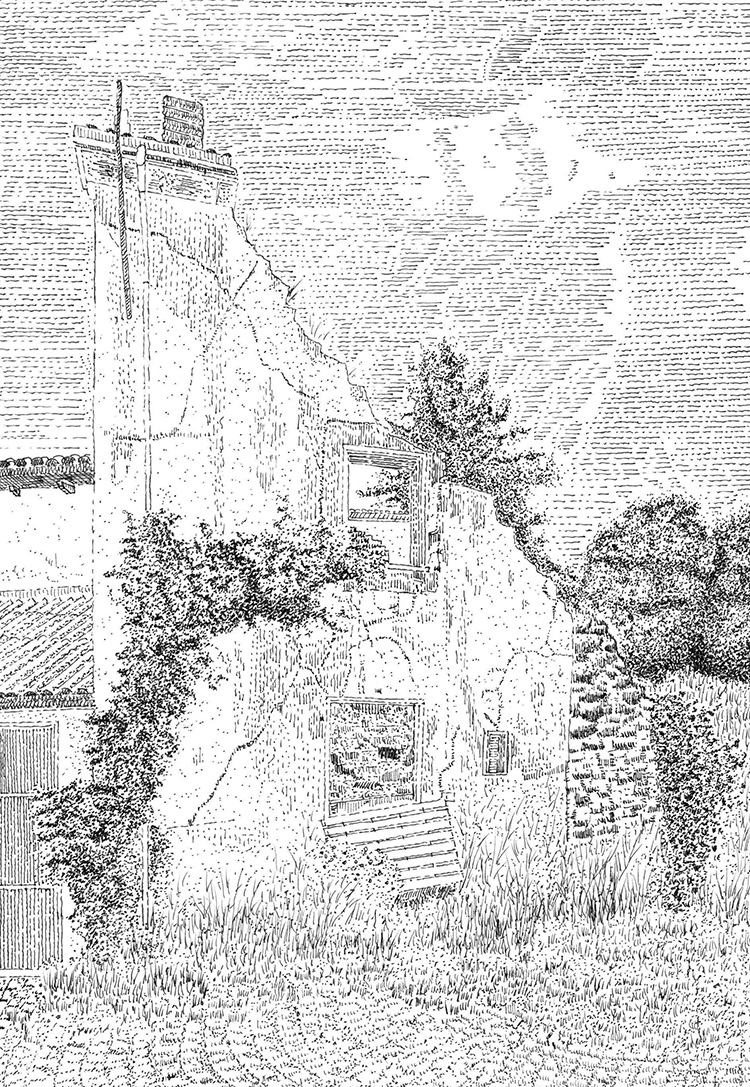

These drawings and photographs are part of an affective topography of some of the Apennine’s earthquake-stricken towns: Coppito, L’Aquila, Onna, Paganica, Campotosto. They intend to describe places not in terms of their objective qualities, but of the subjective corporeal experience these dramatic situations entail. It is, in other words, a hypothetical narrative of Francesca’s sense of presence, what these ruined or rebuilt architectures make her feel, the bodily sensations emerging as she encounters the traces of destruction, the stirrings and movement she empathically feels with the damaged architectural forms; even of Francesca’s corporeal memories, as they lie embedded between her own body and urban space. It is an attempt to sound the deeper stratum of spatial experience, one that clamors to rise when we encounter the dramatic expressivity of the earthquake’s destruction. This form of spatial observation becomes prodromal to design practices that extend beyond the objectual dimension of architecture, crucial in those many cases – natural disasters, war, terrorism – where cities and their inhabitants have suffered and still suffer.

Francesca’s place, beneath the mountains

Coppito

Coppito

Coppito

Coppito

L’Aquila

L’Aquila

L’Aquila

L’Aquila

Onna

Onna

Onna

Onna

Paganica

Paganica

Paganica

Paganica

Campotosto

Campotosto

Campotosto

Campotosto

+

The work presented in this article was produced within the research project “The Affective City”, Department of Architecture and Design, Sapienza University of Rome. All artwork is by the author.

Federico De Matteis is Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of L’Aquila, where he teaches design studios and theory courses. His recent research work focuses on the affective dimension of urban and architectural space, a topic on which he has published books and articles, among which On the natural history of reconstruction: the affective space of post-earthquake landscapes, in Studi di Estetica, 2019; Phenomenographies: describing the plurality of atmospheric worlds (with M. Bille, T. Griffero and A. Jelić), in Ambiances, 2019; Quattro Quartieri. Spazio urbano e spazio umano nella trasformazione dell’abitare pubblico a Roma (ed. with L. Reale), Quodlibet 2017; Affective spaces. Architecture and the living body, Routledge 2021; I sintomi dello spazio. Corpo architettura città, Mimesis 2020; The Affective city/1. Spaces, atmospheres and practices in changing urban territories (ed. with S. Catucci), LetteraVentidue 2021, and the forthcoming edited book The Affective city/2. Abitare il terremoto.

Volume 5, no. 2 Jun-Dec 2022