Complexity-cage: toward a critical deconstruction of “tourism-phobia”

– Clara Zanardi

Tourist go home

Tourism kills the city

This isn’t tourism, it’s an invasion

Tourist: your luxury trip, my daily misery

Introduction

These are some messages that the dwellers of Barcelona have left on the walls of their city during the last tourist season. A semantic web woven by dozens of faceless hands across the urban surface, whose aggregate, albeit its multiplicity, conveys a marked sense of discomfort toward the tourism development, which is affecting the region for several decades and has now probably reached its climax. This adverse feeling has recently found other forms of expression, abandoning the realm of the iconic language toward the direct and active performance. Last summer, for instance, after having organized actions against a bike-sharing equipment and a tourist restaurant in Majorca, members of the anti-capitalist Catalan movement Arran stopped a sightseeing bus on the road, wrote El turismo mata los barrios with spray cans on its front window and slashed one of its tires.

Video: Tourist bus targeted in grafitti attack. Source: El Pais, July 2017.

Video: Organized acts of protest and vandalism in Majorca. Source: Diario de Mallorca, August 2017.

These events have had a vast international resonance and received unanimous condemnation, raising the fear that this modus operandi could mark a turning point in communities’ reactions to mass tourism around the globe, converting the increasingly numerous protests promoted by citizens into violent acts against tourists or tourism infrastructures. On the emotional wave aroused by a similar apprehension, the world press resorted widely and systematically to the “tourism-phobia” label, often describing these and similar coeval phenomena in terms of “hate” or “anti-tourist feeling”1.

1. An analytical examination of “tourism-phobia”

1.1 A big umbrella

In July 2008, El Paìs published an article by the anthropologist Manuel Delgado, introducing the word turistofobia to describe a “frontal rejection to the tourist as an agent of contamination and danger”, to which certain social segments might attribute the cause of the ills suffered by their cities. In short, a “stigmatization device”, which conceives tourists simplistically as invading barbarians2.

Presented here as consequence of a “brutal simplification of real social relations”, the concept ended in fact to represent itself a powerful simplification mechanism to trivialize a highly complex situation. Afterward, it was namely adopted and continuously reproduced by the media as a purely descriptive, self-explicative lemma and applied to a wide and varied set of local contexts and socioeconomic processes. Nevertheless, “tourism-phobia” has not overcome any scientific path of signification yet and is still devoid of a clarified consensual meaning: it is then normally written in inverted commas – typical when words are used metaphorically or there is no semantic level of transparency. The term comes thus as a sort of large umbrella, under which numerous and distinct phenomena are collected and implicitly linked together in a strictly contextual continuity.

Beneath its flaps we can find:

- forms of democratic expression targeting tourism development (public demonstrations, sit-ins, protests);

- any kind of text adopting an oppositional language toward tourism or tourists (journal articles, signs, banners, stickers, murals);

- individual reactions to contingent situations (acts of violence, insults or aggressions);

- politically organized actions against components of tourism industry, like those of Arran;

- political measures promoted by local institutions to regulate or mitigate tourism development (bans on souvenir shops, restrictions on access, imposition of fines to tourist behaviors).

Evidently, a similar juxtaposition sounds arbitrary in absence of an acceptable theoretical justification and such polysemy of “tourism-phobia” might appear in the end more an index of linguistic approximation and conceptual over-simplification, than an indicator of authentic synthetic capacity. Indeed, as long as it gathers phenomena of different origin, deeply rooted in specific local frameworks and pertaining to various sociopolitical levels, a similar category risks assuming and promoting a schematic approach to dynamics of tourism development and to the range of contradictions they engender while permeating each territory.

1.2 Simplification boxes

The schematic approach conveyed by “tourism-phobia” is essentially based on a dichotomous representation of the social implications of mass tourism, where two poles are distinguished and placed at the antipodes. Through the mediation of mass media, a theoretical framework is hence rehabilitated in the common speech, which has been overcome several decades ago in the realm of tourist studies, that is the so-called host-guest polarity3.

This view tends to conceive a fixed representation of the tourist encounter, where two groups of actors are distinct: hosts, supposed to be stably settled in a given place, to share common culture and habits, thus presenting an identifiable character and a coherent univocal attitude toward tourism development; and guests, intended as a de-differentiated mass of people in short transit through that place, with similar interests, desires, practices and behaviors. According to this vision, while the former appears entrenched by a mainly stationary form, the latter emerges as the real agent of the encounter: it is the dynamic factor, whose movement engenerates a new set of consequences, bringing a certain grade of entropy to the fixed figure of the hosting community, like the ball smashing the rack at the beginning of a billiard game.

2. Sticker on a pole, Barcelona. Source: Independent Scot http://www.independentscot.org/turismofobia-in-barcelona/

On a similar basis it has been possible to categorize tourism as an “impact” force, i.e. a single phenomenon capable of inducing direct transformations that can be isolated, brought back to a binary cause-effect relationship and finally factorized through quantitative variables4. An analysis, which in turn has the result of simplifying the complex dialectical process of change connected with tourism development, thus shaping a coercive conceptual schema, which ends up creating an epistemological obstacle for the real understanding of contemporary tourism5.

On the contrary, none of the poles appears to have a monadic nature with pristine and static characteristics. Neither have hosts, whose culture can rather be described as product of a ceaseless, dialectical renegotiation between endogenous and exogenous forces, flowing into a lived experience6; nor have tourists, whose differences in terms of age, provenance, beliefs and aspirations are incalculable7. Moreover, by now hosts are tourists and tourists are hosts without distinguishable breaks in the global web of interconnected mobilities8 and tourism itself cannot be surgically removed as it was a single agent from the interwoven fabric of post-Fordist economy and vast neoliberal development9. As underlined by Bruner, it is then fundamentally imprecise to conceive a local community as a mere passive receptor of an external tourist invader: “rather, both locals and tourists engage in a coproduction: they each take account of the other in an ever-shifting, contested, evolving borderzone of engagement”10.

1.3 The realm of emotion

If the conceptual pregnancy is not the strength of “tourism-phobia”, as we have noted thus far, the lexical contagion, which spread it worldwide, might be explained precisely by the reduction and banalization of complexity it allows. In front of the unknown of a new phenomenon – the expansion of mass tourism to the point of overbooking11 the world -, with the conflicts and not entirely foreseeable consequences that this discloses to our contemporaneity, the dominant approach is that of polarizing its terms, reconducting its dialectical and controversial movement to a simple linear transition. A univocal evolution which can be easily grasped by the common sense and narrated through standardized categories, without really confronting the intrinsic complexity of tourism as an articulated system. As noted by Bauman, this recalls a “longing for certainty in an unstable world”, “an escape from extremely complicated problems” through the principle of “great simplification”12.

Directly correlated to this conceptual operation is a substantial de-rationalization of public discourse on the topic, with the adoption of an emotional language, which leverages on moral sentiments and tends to also misinterpret forms of political dissent and social conflict as mere manifestations of “hate” or “phobia” toward tourists or strangers.

This article aims therefore at deconstructing some implicit assumptions of “tourism-phobia”, which are seldom brought to the surface. This task will be performed by conducting in first instance a brief linguistic analysis, where the notions of tourism and phobia will be considered. Secondly, it will focus on the socioeconomic backgrounds, where the multiple phenomena that comprise the concept have their roots. Given its composite articulation, what we are going to propose cannot obviously exhaust the topic, but simply wishes to stimulate reflection over the intrinsic complexity and contradictory character of tourism development, as we know it in overbooked destinations.

- Tourism. The use of “tourism” in this semantic context presents an insuperable degree of opacity. In fact, the word is neither quantified nor qualified in any specific way. However, what is at play here is not a generic form of leisure, but a truly peculiar one: that mass-tourism characterized by rapid, concentrated and intensive fruition of tourist spaces and by a disproportioned tourists-residents ratio. Indeed, as will be seen later, the onset of social tension in tourist destinations is usually linked to a repeated and systemic violation of their carrying capacity: it concerns places that suffer from overbooking syndrome, while we have no records of similar episodes in locations where tourism development is marginal or inceptive.The processing of a numeric indicator is therefore necessary to deal with tourism and its sustainability: ascribing a diffused intolerance to populations without analyzing their consistency in relation to the quantitative amount of tourist flows is a rhetorical argument that can only be misleading. As underlined by Butler, “in almost every conceivable context, there will be an upper limit in terms of the numbers of tourists and the amount of development associated with tourism that the destination can withstand. Once these levels are exceeded, […] tourism becomes no longer sustainable”13.

Only when the numerical factor has been addressed, it is possible to introduce the qualitative aspect of tourist practice. Refusing to identify a single type of tourism, or a standard generalized form of tourist experience14, the diverse influence that different kinds of tourist presence have on local communities must be considered: a cruiser, a single excursionist, an overnight tourist, a second-home owner have distinct habits and requirements, for their reverberation on local situations can also vary notably15. Speaking of “tourism” in vague terms might then be of little significance, when its numerical force and modality of space fruition are not taken into account.

- Phobia. Phobia is usually defined as “an extreme or irrational fear of or aversion to something”16. Implicit in the term are thus two concepts: emotional irrationality and exaggeration. In other words, speaking of “phobia” means that the reaction of fear in relation to something is not proportionate to the real danger it represents for the person who feels it. If so, how could we justify the application of a similar concept to forms of prompt reaction toward the time and site specific process of tourism development?Moreover, the common use “tourism-phobia” tends to be articulated as hate toward tourists, an arbitrary connection, which gives the term an even further pejorative meaning. “Hate” refers, in fact, to the realm of ancestral sentiments and tends to overshadow the rational reasons behind similar oppositions, leading us to associate them with regressive sociocultural phenomena, as racism toward strangers or immigrants, fear of otherness, antisemitism or “Islamophobia”. This conceptual shift enables then a transfer from a sociopolitical object, that of tourism development as socio-technical rhizome17, to a personal and indiscriminate attack against tourists, ordinary unaware people simply enjoying their free time. Therefore, the passage from tourism to tourists is not a detail, but a matter of substance: once more the question of tourism development is depoliticized, devoid of social or cultural legitimacy and offered up for moral judgment, which can only be of unanimous condemnation.

Nevertheless, every group, movement or individual accused of “tourism-phobia” refuses the label and specifies clearly that his target is not at all the tourist, but a certain type of system of tourism. The public statement of Arran, for example, is unequivocal: “Against the model of tourist massification. Our actions and our speech are not against tourists, but against those who really make money on tourism, who are not the small traders, but the big companies”18.

3. Protest against the touristification of Barceloneta. 30th of August, 2014. Source: Victor Serri, Flickr.

2. A socioeconomic contextualization

Now that we have analyzed the linguistic assumptions of the term and specified that the type of tourism we are dealing with is mass-tourism, we can now try to briefly sketch the articulated context from which “tourism-phobia” derives. Contemporary tourism being an articulated phenomenon, deeply linked to global flows of mobility and actual modes of economic production, it would require a multiscale analytical model that interweaves elements of different scales, which are investing in one territory, and considers at the same time all territories synchronously shaped by that same weaving19. Following this ideal model, albeit readjusting it to the concise space at our disposal, we are going to outline three levels, different but interconnected, on which tourism development exsists, highlighting the points of friction that can unfold. This is undertaken with the fundamental premise that layers are to be conceived in a processual mode, as scale stands for a temporarily stabilized effect of a plurality of sociospatial processes in a continuous movement of rescaling20.

- Macro – Global processes. Pertaining to the aleatory dimension of leisure, tourism is often considered as an isolated and niche phenomenon, a postmodern, superstructural bauble21, whose real importance for our economies is mostly underestimated. As a consequence, we tend to disclaim that it could actually be framed as a true ordering22, a complex and branched system capable of disposing and giving shape to contemporary realities, gradually re-structuring places, economies and societies.

As reported by UNWTO, tourism has experienced continued growth in last decades, acquiring a key role in any process of socioeconomic development. Today, its business volume equals or even surpasses that of oil exports, food products or automobiles, being one of the major players in international commerce23. As a “global process of commodification and consumption involving flows of people, capital, images and cultures”, tourism is thus not a self-contained sphere nor a neutral choice or natural destiny for territories, but “one aspect of the global processes of commodification” inherent in modern capitalism24.

From the capitalist mode of production, tourism therefore derives risks and contradictions: First of all the tendency to acquire the form of an advanced extractivism and turn into a monoculture. Through a tourist economy, in fact, the basic resources of a territory (landscape, natural reserves, transport, infrastructure, urban space, real estate, local culture, heritage…) competitively enter the market, triggered by consecutive processes of “accumulation by dispossession”25, where surplus value is created through the private acquisition of public assets and a side is lent to financial speculation over basic use values26. Moreover, due to its high and fast profitability and to the low rate of investment required to access the business, the tourism industry can easily accelerate crowding-out effects of other forms of economic activity and commerce27.

Despite this profile, tourism is often presented to the people as the optimal option to achieve economic well-being, relying on the short-term returns it promises, its green film and its labor intensive use to cover contingent cash deficits of countries, which are going through challenging processes of de-industrialization. On such premises, the globally diffused tendency is that of letting the business grow with as little disturbance as possible, often accelerating the development process without facing its social and environmental costs, nor disposing appropriate regulatory measures to mitigate its criticisms.

- Meso – Local patterns. How this declination of the world economy interweave different in local contexts? Every situation being irreducibly specific, we will here cite the case of Spain, origin and focal point of what has been termed “tourism-phobia”, limiting ourselves to present two exemplary occurrences frequently connected with tourism development: the impasse of governance and social harm.

Deeply affected by an economic crisis in 2011, especially acute in the domain of real estate, Spain has focused even more efforts on the already consolidated tourism industry, in order to revitalize the economy and curb rampant unemployment. As a result, it has broken all records in 2017, attracting 82 million visitors and replacing United States as the world’s second most popular tourist destination. Has this astonishing growth equally benefited the local population and truly enriched the country? Has this high rate of development produced a consistent increase in the quality of life of involved communities? In fact, the degree to which these effects could be actualized heavily depends on the level of management and legislative control that local governments are effectively able to exert on the whole process. In turn divided into different spheres of competence and successive layers of jurisdictional power, often pushed by the lobbying pressure of forceful groups of interests, local authorities seldom have the authentic willfulness, or the administrative availability, to adequately rule and direct tourism development. Yet this lack of coordination can have dramatic consequences on local communities, turning a golden goose into a real threat, as becomes clear in at least two fields: (1) the so-called overbooking syndrome and (2) the real estate market.

1) When the numerical increase of attracted visitors is the main indicator of economic success, it is easy for a locality to incur in a frequent or systematic violation of its carrying capacity. The concept of carrying capacity encloses both “the maximum number of visitors that can be absorbed by a tourist attraction” – a quantitative datum referring to the physical limits imposed by the structural condition of the place -, and “the number of visitors the city can absorb without hindrance to its other social and economic functions”, a qualitative criterion, accounting for the degree of heterogeneity that can keep being safeguarded in the site28.

If this criterion is not considered and the actual carrying capacity is regularly overloaded, the local community can experience a concrete sense of being overwhelmed and in peril. Indeed, when asked about their main concern nowadays, Barcelona’s dwellers have answered that before unemployment, traffic, municipal management and access to housing, the worst problem they have to face is tourism29.

The quantitative variable turns into a matter of absolute substance, since it determines a qualitative transformation: With a certain amount of daily repeated overcrowding, a place risks deteriorating its proper quality of life and undergoing a complex process of metamorphosis, gradually loosing its place-specific features and sociocultural unique texture.

2) Nowhere is the capitalist contradiction between use value and exchange value so acute as on the space of social reproduction par excellence, the house. When converted into an asset of safe and profitable investment – an outcome simplified by innovative ways of commercialization like holiday rental platforms -, houses acquire an exchange value, whose disproportionately high rate often ceases to bare the roots of their primary and previous function: inhabiting. In Spain, where Airbnb, Booking, TripAdvisor and HomeAway hold more accommodation capacity than the hotel industry, the real estate bubble of 2008 had induced tens of thousands of Spanish, prostrated by the high rate of unemployment, to become small entrepreneurs in themselves, extracting income from their home in order to cover mortgage rates. This has in turn produced an exponential increase of rental and house prices, making it more difficult for the weakest social classes to find an affordable place where to live and accelerating the direct and indirect displacement of local populations30.

While the work offered by the tourism industry is mainly low qualified, precarious and low paid, lowering the average annual income per capita31, the cost of life and basic goods in tourist destinations becomes increasingly high, dramatically deepening the gap for locals between the necessary income for living in the place and their actual disposability32. This has the potential to produce a deeper level of inequality, with new forms of poverty and social disease33. The case of Balearic Islands is quite surprising in this sense: despite having exceeded every record of tourist arrivals (hosting 14 millions international visitors in 2017, + 6,1% over 2016), the region suffers a high rate of poverty: 10,4% of the population, almost 115.000 persons, lives under extreme indigence, trying to survive with less than 332 euros per month despite the standing rise of living costs. In total, 26,3% of the inhabitants of the archipelago, 290.000 persons, live under the risk of poverty and social exclusion34. This means the level of poverty in the region is over the national average (7,6%), just under Andalusia (which is in turn fourth for tourist arrivals, more than 11 million, + 9,2% over 2016) and the Canary Islands (third with almost 13 million visitors, + 7,9%)35.

- Micro – Individual experience. This complex transformation of localities, characterized by a peculiarly high speed, directly involves inhabitants, both at a community and individual level. Every day, they have to manage the distress of a sweeping change in their living environment and constantly adapt and mould their habits to the frantic pace of the tourist city. The common trait emerging from their narrations is indeed a perceived collapse of the quality of life, due to the overlapping of multiple factors: environmental and acoustic pollution, congestion of public transport, overcrowding of public spaces, increasing privatization of communal areas, desertification of economic diversity, depletion of the commercial fabric, difficulties in regular sleeping, lost of habitual meeting places, fraying of social relationships, alteration of residential components of neighborhoods, conversion of traditional feasts into tourist events, commercial reification of local specificity.

Moreover, as the tourist economy spreads and consolidates in a given place, many individuals find themselves entrenched in the insuperable contradiction of being economically maintained primarily by the fruits of that same becoming, which is negatively affecting their lives (the Airbnb host probably being the most obvious example). This means they realize the negative externalities of tourism monoculture, personally experiencing its effects, but are interested at the same time in maintaining the status quo to avoid the lost of an important source of revenue, even more precious in times of economic stagnation and fiscal austerity. A paradoxical condition, which fosters social polarization of communities and can easily become a fertile soil for discontent and frustration.

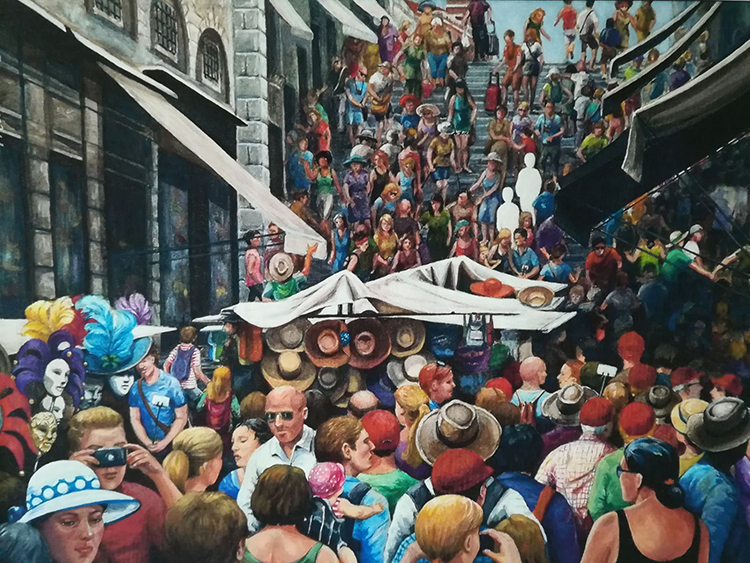

Seeking a recomposition of these levels after their analytical subdivision, we could detect a possible line of intersection in the concept of disorientation. A deep sense of disorientation is, in fact, what local populations feel when facing tourism development: a macro-global process, which accelerates meso-local transformations, sharply affecting their micro-everyday lives, but over which they realize they have little decision-making power and control. The awareness of the transformative potential of an intensive tourism development might thus be accompanied by a bitter sense of disillusion, that of a broken promise. The actuality of living in an overcrowded thematic park, assisting the progressive loss of life quality, contrasts vividly with what governments have claimed for years: tourism bringing wealth, well-being, regenerated cities, efficient infrastructures, renovated houses, cosmopolitan atmosphere, full employment and progress. Communities then begin to realize that the assured trickle-down effect of tourism development is not automatically connected with the exponential growth of the system, since a multilayered set of conditions has intervened to curtail the expected redistributive process and environmental and social limits to growth are emerging with progressive poignancy. “The long-awaited presence of visitors begins to change in aversion because the model is expelling the native population, unable to follow the vertiginous increase in the price of rents, hotels and commerce, in addition to homogenizing and deforming the identity of the city, altering life habits and collapsing services and infrastructures that are paid by all citizens”36.

4. Disorientation, or Find the Venetian. Image: Marina Jovon, Antico Teatro di Anatomia, Venice. Photo: Author.

Conclusions

This article started by briefly retracing the mediatic path that clarified “tourism-phobia” in the public discourse during the last tourist season, conveying in this a conceptual frame to account for different kinds of reactions to tourism development around the world. As we saw, the adoption of this concept is far from a neutral or merely descriptive choice, for at least two reasons. First of all, it presupposes an inaccurate notion of tourism, which escapes every quantitative or qualitative determination and tends to hide its systemic character, shifting the narration to tourists as singular individuals and hosts as hostile homogeneous groups. Secondly, by using an emotional language, it tends to flatten the intrinsic complexity, which permeates processes of tourism development in specific socioeconomic contexts, implicitly depriving every form of dispute advanced by involved communities of political legitimacy. “Tourism-phobia” represents thus at the same time the producer and the product of an inadequate discourse on tourism: by constructing a formidable complexity-cage, it offers an essential instrument to avoid any valid interpretation of recent circumstances and, at the same time, it is itself the result of a narrow theoretical paradigm.

After this semantic and conceptual scrutiny, the article has tried to offer an alternative way of considering the multiplicity of phenomena collected under the label “tourism-phobia”. Resorting to a multiscalar approach, the complex dynamic of mass-tourism development has been schematically subdivided in three interwoven levels (the macro-global, the meso-local and the micro-individual), briefly detecting their basic features and highlighting some correlated criticisms or tension nodes. The three frames were then reconnected around a common element, that has been identified as the sense of disorientation – which the fast pace of ungoverned tourism development can induce in local communities.

The contextualization of this sentiment has been necessary to support the thesis that those acts we normally define “tourism-phobic” cannot be merely considered as irrational outbursts of intolerance against tourists. On the contrary, they constitute forms of political agency, trying to confront an extremely complex, multilayered and critical process. Of course, they do have different degrees of awareness, organization, focus and consistence, and can even assume the traits of a frustrated hostility against single visitors or stereotypical categories of tourists. However, the classification of all this composite galaxy as “phobic” cannot hide the necessity to answer the basic questions it raises. In fact, despite their absolute heterogeneity, these reactions all seem to originate from an actual balance breakdown, i.e. that violation of carrying capacity of tourist places, which compels visitors and locals to compete for limited and non-reproducible resources and to contend the same restricted space.

When omitting all this, “tourism-phobia” tends to function as a delegitimization technique, set in motion “to discredit a completely legitimate struggle”37 and disqualify the actions of denunciation carried out by social movements by pathologizing and individualizing a concrete social malaise, thus concealing that the problem lies in the system, not in the subjects38. Therefore, the degree to which intolerance and frustration, arisen by factual conditions, will manage to assume a non-alienated or regressive shape and become engines of genuine change and political improvement depends also on whether we will become capable of listening to their rational reasons. That is to say, we must make an effort to challenge the multilayered and interwoven nature of tourism development and focus on the contradictions it raises, stimulating the contemporary political debate to confront them in their actuality.

Notes

1. See for example:

– H. Coffey (May 2017). Eight places that hate tourists the most. The Independent, [online]. Available from: http://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/places-hate-tourist-the-most-countries-ban-visitors-venice-thailand-amsterdam-japan-onsen-santorini-a7733136.html [Accessed 15 May 2017].

– A. Lopez Diaz (August 2017). Why Barcelona locals really hate tourists. The Independent, [online]. Available from:http://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/barcelona-locals-hate-tourists-why-reasons-spain-protests-arran-airbnb-locals-attacks-graffiti-a7883021.html [Accessed 09 August 2017]

– W. Coldwell (August 2017). First Venice and Barcelona: now anti-tourism marches spread across Europe. The Guardian, [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2017/aug/10/anti-tourism-marches-spread-across-europe-venice-barcelona [Accessed 10 August 2017].

– F. Olivo (August 2017). In Spagna è “turismofobia”, i residenti contro i vacanzieri: “Vandali, ubriachi e low cost”. Il Secolo XIX, [online]. Available from: http://www.ilsecoloxix.it/p/mondo/2017/08/08/AStxxNlI-residenti_vacanzieri_turismofobia.shtml [Accessed 8 August 2017].

2. M. Delgado Ruiz (July 2008). Turistofobia. El Pais, [online]. Available from: https://elpais.com/diario/2008/07/12/catalunya/1215824840_850215.html [Accessed 12 July 2008].

3. See:

– E.M. Bruner (2005). Culture on Tour. Ethnographies of Travel. The University of Chicago Press.

– J. Urry, J. Larsen (2011). The tourist gaze 3.0. Sage.

– K. Meethan (2001). Tourism in Global Society. Place, Culture, Consumption. Palgrave.

4. K. Meethan (2001). p. 143.

5. M. Picard (1996). Bali. Cultural Tourism and Touristic Culture. Archipelago Press, p. 104.

6. K. Meethan (2001). p. 135.

7. E. Cohen (1979). A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology, 13.2, pp. 179-201.

8. J. Urry, J. Larsen (2011). p. 64.

9. K. Meethan (2001). p. 162.

10. E.M. Bruner (2005). p. 18.

11. E. Becker (2016). Overbooked: the Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism. Simon and Schuster.

12. L. Galeck, Z. Bauman (December 2005). The unwinnable war: an interview with Zygmunt Bauman. Open Democracy, [online]. Available from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/globalization-vision_reflections/modernity_3082.jsp [Accessed 1 December 2005].

13. R.W. Butler (1999). Sustainable tourism. A state‐of‐the‐art review. Tourism Geographies, 1.1, pp. 7-25.

14. See:

– E. Cohen (1979).

– T. Edensor (2001). Performing tourism, staging tourism. (Re) producing tourist space and practice. Tourist Studies, 1.1, pp. 59-81.

15. A.P. Russo (2002). The “vicious circle” of tourism development in heritage cities. Annals of Tourism Research, 29.1, pp. 165-182.

16. Oxford Dictionary [online]. Available from: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/phobia

17. A. Franklin (2007). The problem with Tourism Theory, in I. Ateljevic, A. Pritchard, N. Morgan, The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies. Innovative Research Methodologies. Elsevier, p. 143.

18. Arran, (August 2017). Comunicat sobre les darreres accions de denúncia del model turístic dels Països Catalans. [online]. Available from: http://arran.cat/blog/2017/08/06/comunicat-sobre-darreres-accions-denuncia-model-turistic-dels-paisos-catalans [Accessed 6 August 2017].

19. Saskia Sassen (2007). A sociology of globalization. Análisis Político, 20.61, pp. 3-27.

20. N. Brenner (2009). Restructuring, rescaling, and the urban question. Critical Planning, 16.4, pp. 61-79.

21. M. D’Eramo (2017). Il selfie del mondo. Indagine sull’età del turismo. Feltrinelli, p. 12.

22. A. Franklin (2007)..

23. UNWTO. Why tourism? http://www2.unwto.org/content/why-tourism.

24. K. Meethan (2001). p. 4.

25. D. Harvey (2004). The “new imperialism”: Accumulation by dispossession. Actuel Marx, 1, pp. 71-90.

26. See: L. Camargo (September 2017). Entrevista a Ivan Murray. Turismo, urbanismo y capitalismo. Viento Sur [online]. Available from: http://www.vientosur.info/spip.php?article13034 [Accessed 25 September 2017].

27. A. Cócola Gant (2015). Tourism and commercial gentrification. [Conference Paper] In: RC21 International Conference The Ideal City: between myth and reality. Representations, policies, contradictions and challenges for tomorrow’s urban life, Urbino (Italy).

28. J. Van der Borg (1991). Tourism and Urban Development. Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, pp. 53-54.

29. C. Blanchar (June 2017). El turismo ya es el principal problema de Barcelona, según sus vecinos. El Pais [online]. Available from:https://elpais.com/ccaa/2017/06/23/catalunya/1498212727_178078.html [Accessed 23 June 2017].

30. A. Cócola Gant (2018). Tourism gentrification. In L. Lees, M. Phillips, Handbook of Gentrification Studies. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

31. E. Cañada (November 2017). ¿Por qué se precariza el trabajo turístico? ALBA SUD [online]. Available from: http://www.albasud.org/blog/es/998/por-qu-se-precariza-el-trabajo-tur-stico [Accessed 2 November 2017].

32. J.L. Barbería (August 2017). Turismofobia, ciudades de alquiler. El Pais Semanal [online]. Available from: http://elpaissemanal.elpais.com/documentos/turismofobia/ [Accessed 8 August 2017].

33. See: A. Cócola Gant (June 2015) Gentrificación y turismo en la ciudad contemporánea. ALBA SUD [online]. Available from: http://www.albasud.org/noticia/es/747/gentrificaci-n-y-turismo-en-la-ciudad-contempor-nea [Accessed 24 June 2015].

34. Diario de Mallorca. (October 2016) Un 10,4% de los baleares viven en pobreza extrema. Diario de Mallorca [online]. Available from: http://www.diariodemallorca.es/mallorca/2016/10/13/10-baleares-viven-pobreza-extrema/1157051.html [Accessed 13 October 2016].

35. La Vanguardia. (January 2018). Récord de llegadas: Más de 82 millones de turistas internacionales han viajado a España en 2017. La Vanguardia [online]. Available from: http://www.lavanguardia.com/economia/20180110/434208713049/datos-turismo-2017-record-llegadas-turistas-internacionales.html [Accessed 11 January 2018].

36. J.L. Barbería (August 2017).

37. Arran (August 2017).

38. Horacio Espinosa Zepeda (July 2017). Turismofobia: Patologizar el malestar social. El Diario [online]. Available from: http://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/opinions/Turismofobia-Patologizar-malestar-social_6_660443975.html [Accessed 3 July 2017].

Clara Zanardi is a PhD student in Urban Anthropology at the University of Trieste, Italy. With background studies in Philosophy and Anthropology, her current research explores in a critical way the relationships between tourism, urban areas and local communities. Her case study is Venice (Italy), where she lives and works. She is also politically active in the field and participates in the international network “SET” (Southern Europe facing Touristification).

Volume 2, no. 1 Spring 2019