‘Gentritourism’ and the subculture of visitors emerged from it

– Cristina Roxana Lazar and Elisa Diogo Andrade Silva

Tourism nowadays has become an industry that is increasingly influencing the way in which cities are planned and especially the direction towards which they are developing. From the cities most popular among tourists in Europe such as Barcelona, Paris, Berlin and London, to small Asian communities, the idea of tourism as an economical catalyst is expanding. Alongside the positive effects, there are also side effects that leave their mark on sites, and contribute to their transformation and sometimes loss of identity. This article aims to present concepts of global tourism and gentrification, and to draw a parallel between them, highlighting a new type of tourism- ‘gentritourism’ and the subculture of visitors created by it. But first what is global tourism and why is it important for place development nowadays?

In order to start defining global tourism, the term needs to be divided into two known processes, tourism and globalization. Tourism is known as a commercial business, which gains its resources from the planning, promotion and sale of visits to places of interest for the mass public. It emerged in the ‘50s and has proven to be one of the fastest growing industries with impacts on economy, society, culture, art, land and the environment. Nowadays, the impact generated by tourism on the previously mentioned sectors, namely society, land and the environment, is mainly considered to be a negative one (Gunn, 1994).

The process of globalisation is seeing international influences more and more present in cities, creating a polemic between global and local [Image 1.]. Bull in 2013 in his book Cross-Cultural Urban Design, looked back to 1991 to quote Jameson: “A characteristic of the present time is that worldviews must come to terms with the increasing exaggeration of both the global and the local”. Jameson then defined the idea of ‘post-modern hyperspace’ as “that stretching of space and time to accommodate the multinational space of late capitalism” (Jameson, 1991). The concept of ‘hyperspace’ is relevant in this context, as it can be redefined through the process of global tourism. Global tourism is characterized as the phenomenon that enables international influences within the touristic attractions and creates “‘new users’ of the city: the footloose, international tourists, business travellers, entrepreneurs, innovators and investors who can take their consumption, interests, creativity or investments wherever they choose” (Sassen 1999 in Bull, 2013). What further characterizes the ‘new users’ of the city is their flexibility regarding travelling and relocating, which generates the idea that the process of globalization is high-speed and facilitated by tourism, contributing therefore to the constant change of the urban space.

1. “Global values”

The illustration refers to the phenomenon of global tourism and it represents an abstract perspective upon the topic. Its aim is to highlight a tendency of imitating cultures and values, therefore the illustration gathers multiple elements from around the globe, such as human agglomerations, buildings and advertisement clusters. It also aims to illustrate that local and authentic is becoming in most cases ordinary and not so interesting for the general audience. Source: Authors.

Over the last few decades, the industry of mass tourism has changed the way cities and communities behave and look worldwide, by processes such as city centre restructuring, ‘commodification’ of leisure activities (Judd, Fainstein, 1999) and gentrification. Gentrification is a socio-urban process which has been first described in the 1960s by sociologist Ruth Glass regarding the changes within the city of London. Over the time the term has been given various definitions and one of the most succinct is that gentrification refers to “the transformation of a working-class or vacant area of the central city into middle-class residential and/or commercial use” (Lees, Slater and Wyly, 2013). Even if the phenomenon of gentrification started within large cities, nowadays it has spread in numerous places and different contexts, following the process of urbanization and therefore “the result seems to be that even some Third World cities and First World suburban and rural areas are experiencing gentrification.” (Lees, Slater and Wyly, 2013). The major downside of the gentrification process is that the next step after ‘redesigning’ and changing the perspective on a district or a neighbourhood is the “booting out in forthcoming years as landlords transformed the artists’ studios into residential co-ops for the wealthy” (Currid, 2009). Taking into account the above mentioned definition for gentrification, economic reasons seem to play a key role, as the ousting of the working-class is done through the rise of lifestyle costs. This article aims to draw a parallel between gentrification and tourism and to find a solution for specific contexts in which existing and new communities can cohabit in a sustainable and community-oriented manner.

Without disregard for the negative impacts of the gentrification process upon social equity and geo-demographical homogeneity, the concept of gentritourism (described in the following segment of the article) will focus on David Ley’s theory about the ‘new middle class’ that emerged in the 1970s. Ley was inspired by David Bell’s Post Industrial Thesis, which states that there is a shift in the economy of the post-industrial society from manufacturing to service-based; universities replace factories and there is a rise of managerial professions and “artistic avant-gardes lead consumer culture” (Bell, 1973 in Lees, Slater and Wyly, 2013). The factors mentioned by Bell stimulate change, often in the form of a gentrification process, and are the reasons for which ‘gentrifiers gentrify’. Later Ley affirms that a ‘cultural new class’ emerged with “a vocation to enhance the quality of life in pursuits that are not simply economistic” (Ley, 1996) and argued that the process of gentrification takes now also into account factors like particular aesthetics, taste and “ an alternative urbanism to suburbanization” (Ley, 1996). Closer to the present, Robert Florida’s book entitled ‘The Rise of the Creative Class’ (2003) argues that nowadays in order to capitalize new economies, policy makers must take into account the ’creative class ‘ “that is gays, youth, bohemians, professors, scientists, artists, entrepreneurs and alike” (Lees, Slater and Wyly, 2013) and even calls them the key factor to economic growth. This being said, the process of gentrification is changing and the gentrified sites can sometimes be identified in specific contexts by a clash of art and culture. Berlin provides a good example, as it is especially known “as a young, creative and emergent metropolis” (Smartcitiesdive.com, 2017) and one of the places where the process of gentrification and its participants feel like home. After the Berlin wall fell, parts of the eastern inner city were no longer inhabited, therefore at that time young people, artists and immigrants moved in the places where nobody wanted to live. In time they managed to create a subculture which nowadays attracts visitors and is conscientiously used by local governments as a touristic magnet (Smartcitiesdive.com, 2017). Nowadays, “locals are opposing a plan to demolish Communist-era apartment blocks in a prime city centre location and replace them with upscale homes and shops” (Morris, 2017).

Gentrification therefore has both positive and negative aspects [Image 2.] and in the following of this article, the idea is to harness the positive ones via the concept of gentritourism and the subculture emerging from it, the ‘gentritourists’. Before defining gentritourism, the following question must be answered: How does tourism influence gentrification and what are the consequences?

2. “Gentrification zoo”

The second illustration intends to present a surreal perspective of a gentrified city district, where good and bad cohabit inside the process of gentrification. On one side there are the dwellers who feel included in the community and on the other side, in the rest of the city, more and more areas are being threatened by globalization and capitalism. The last ones will eventually lead to the destruction of local values and vernacular identity. It is entitled “Gentrification zoo” as it is similar to a jungle, where the strongest economically perseveres, like inequity among social classes. Source: Authors.

Globalization and mass tourism are having a large impact around the world as mentioned in the beginning of the article and gentrified districts make no exception. In large and highly touristic cities in Europe such as Barcelona, Paris, London, Berlin, Lisbon, and Amsterdam gentrification is being influenced by tourism, as rent gaps between central and peripheral areas are increasing and locals are being ousted from their residences in order to accommodate tourists for exaggeratedly high prices. Small local businesses are being threatened by worldwide known fast-food restaurants or globalised imitations of specific local food, where pizza and burgers have become traditional dishes everywhere. A good example is Barcelona, a major destination among European cities, which is nowadays suffocated with tourists, souvenir shops and touristic buses. ‘Bye Bye Barcelona’ is a documentary which illustrates the locals’ dissatisfaction and anxiety caused by the extremely large number of tourists visiting Gaudi’s masterpiece city every year, and in all seasons. The citizens of Barcelona are complaining about the fact that the city no longer belongs to them, that it is highly overcrowded and overbooked, and visitors’ presence is increasing even in local residential areas. This all results in the loss of a sense of community, an increase in rents and lifestyle costs, traffic jams, lowerd levels of security and high commercialization of local values and traditions (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014).

By merging of global tourism and gentrification, the concept of gentritourism is born. The term of gentritourism is used to describe how tourism can influence the areas caught in the process of gentrification in a positive way, within specific contexts. The idea is to develop a process through which gentrified areas are transformed and improved by old and new users (gentritourists) in a manner that allows all of them to cohabit and build a sense of community, without losing the essence of social and economic equity. Gentritourism can be applied in urban contexts within which the gentrification process has either taken place already or will in the nearby future. It can work either at large or small scale, with different levels of impact. A hypothetical example would be if the principles of the gentritourism as described above, would be applied at large scale within a district in a popular tourist city, where the sense of community is less felt and the gap between the social classes is be bigger, therefore the level of social and economic equity lower. One direction which might be followed in this kind of case would be that people would group according to similarities between them (e.g. artists’ district) and find a way to decrease socio-economic gaps, keeping in mind a side effect might be that the opposite occurs and the differences between them become barriers. Whereas on a smaller scale, community-based and sustainable tourism would be more feasible and achievable, as it would define a lifestyle which does not build itself on consumerism and economic hierarchy.

The subculture emerged from the implementation of gentritourism is the ‘gentritourists’, as a derivation from the concept’s name. In this context, ‘gentritourists’ will be fitted into a social category that might seem stereotypical, but it is just in order to be presented in a clear format open to all levels of understanding. The idea of ‘Gentritourists’ has its basis in a further study made by David Ley in the 1990s, where he turns his attention to the three biggest Canadian cities (Toronto, Montreal and Ontario), in order to observe the typology of people predominantly living within the gentrified areas. Ley affirms that “the principal gentrifying districts in each city in fact contained an electorate which predominantly sided with more left-liberal reform politics” which “prioritize a more ‘open’ government concerned with neighbourhood rights, minority rights, improved public services (..) and greater attention to heritage, environment, public open space, and cultural and leisure activities” (Ley, 1996). As David Ley also argues, the ‘new middle class’ (Ley, 1996) has grown tired of the suburbia and is looking for an exciting place to live, where they do not feel isolated and where costs, from transportation to leisure activities, are much lower. Furthermore, D. Ley and R. Florida both argued that the ‘new middle class’ is bohemian and does not define its lifestyle choices by economic status.

Keeping these observations in mind, ‘gentritourists’ can be defined as users of the gentrifying areas, who approach the districts as world visitors, sustainable tourists and have an interest in living there for long or short term. Their aim is to discover a different culture, to be new in an unknown environment, to stay longer than a normal tourist and also to not emerge in actions which can damage the vernacular identity of the place, the environment or socio-economic situation. Gentritourism can be used in order to suggest how and why ‘new users’ (Jameson, 1991) would be drawn to specific places in the world, based on who they are and what they are looking for. The ‘new users’ can be identified in this situation with the gentritourist and can range from international tourists and backpackers to entrepreneurs, innovators and investors which are encouraged to take their consumption, interests, creativity or investments (Jameson, 1991) within the gentrifying areas. More specifically, gentritourism welcomes new inhabitants, and their perspectives on the place, as long as they develop within an innovative and beneficial realm and do not harm the wellbeing of the community and its economic balance. Nevertheless gentritourism does not aim to create gated communities or isolated districts, but to continue to make the poorer or emptier parts of the cities liveable again and generate an identity attractive to new and old dwellers, in the areas where the concept fits with the existing context. ‘Gentritourists’ are part of the middle and lower economical classes, therefore do not encourage the price increase of rents and lifestyle, but rather a ‘financially safe’ place where locals and visitors alike feel protected and part of a continuously blossoming community. In such a situation, gentritourism could be a solution to start with, as it would attract indeed new users, but the ones who are investing into making a good change for the city and building place identity, not just consuming the touristic attractions. The concept however does not apply in all contexts and situations worldwide, as it is not the solution to all the negative effects of global tourism.

So, how can gentritourism help the gentrifying areas improve in a manner that does not generate a negative impact upon the local identity or lead to ousting the inhabitants? Community-based tourism refers to an alternative way of travel, which seizes the economic opportunities of communities, while preserving the cultural identity and trying to have as low negative impact as possible upon the local culture and environment (Salobol, 2004 in Bull, 2013). Therefore, following the idea of applying the concept of community-based tourism within gentritourism in specific contexts (small-scale), the result will be that travelling through those districts would be truly authentic and less like being in a neighbourhood which has been conscientiously designed to be commercial and easily consumed by temporary users (view the Soho Effect detailed by E. Currid). Simultaneously, it will create affordable residences and will protect the inhabitants from being evacuated or isolated while preserving the place’s vernacular identity. The situation presented might seem ideal, with the note that before reaching the mentioned positive outcome, other measures have to be implemented, as gentritourism is not a concept claimed to solve all negative aspects. Some of the actions that could be implemented in order to be able to apply the concept of gentritourism are a study regarding the number of residents already living there, including the ones in danger of being ousted and finding a convenient solution for all, such as social housing, implementation of energy saving tools, such as solar panels and thermal insulation of the buildings.

To give a broader picture of the role of tourism within the concepts defined above, the idea of the gentritourist as a world user is put forward. The same user (gentritourist) can play either the role of the dweller within a gentrifying district or the one of a tourist elsewhere in the world. So, how does a gentritourist behave when he/she is outside of the gentrifying district zone? What kind of places is he/she interested in visiting and why? Does his/her behaviour of gentritourist create a pattern and maybe a new typology of visitor?

In order to find answers to these questions, the idea of the subculture created through gentrification must be clarified first. The social typology of people initiating or being drawn to gentritourism and processes alike is not fixed or rigid, but some common traces can be noticed. Scott discusses about certain places like New York, Berlin, Paris, Barcelona, London, Melbourne and so on, which are “irresistible to talented individuals who flock in from every distant corner in pursuit of professional fulfilment” (Scott, 2004 in Currid, 2009). In other words, ‘gentritourists’ can define a niche of people who are attracted to a place due to its creative vibration, unconventional mindset, artistic and cultural potential and not the least, opportunities to work and be part of a like-minded community.

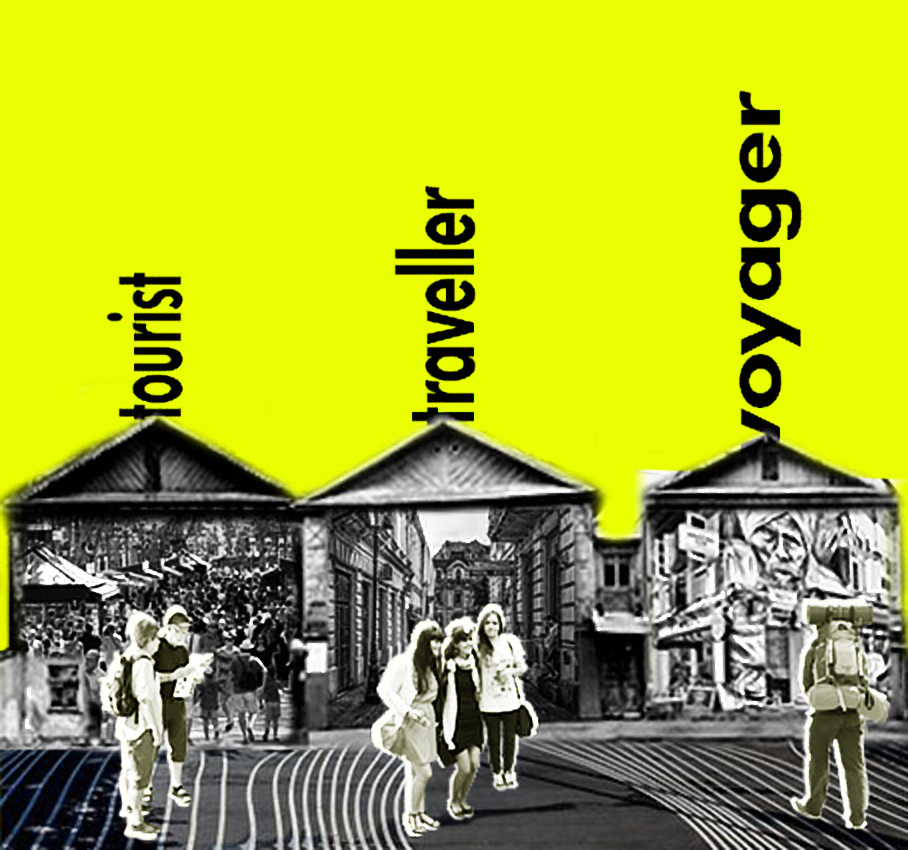

Furthermore, in order to define the idea behind ‘gentritourists’, a more detailed classification of tourists is first necessary. In this way, three categories are contoured within the process of visiting: the global tourist, the traveller and the voyager.

The first of them, the global tourist is considered to be the one who seeks commercial experiences, in most cases having a closed holiday package purchased within a touristic agency, limiting his freedom of choice (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014). The typical global tourists form the social group of consumers which create the most damage while visiting foreign places, as they are not looking for authenticity or local experiences. They are comparatively interested in high-speed commercial contact, so more aimed on quantity, rather than quality without any particular sense of caring for the well-being of the visited places and communities. The second visitor category refers to the traveller, a typology which offers some room for improvisation regarding the journey’s itinerary. The traveller is not a rigid stereotype of visitor, but rather orbiting between the tourist and the voyager, as it ‘borrows’ traces from both.

The third typology of visitor is the voyager and it makes a direct reference to the subculture created due to gentritourism. Bull discusses a new segment of tourists emerging in recent years, describing them as foreigners who are looking for exotic hidden places and “cultural landscapes in resort enclaves” (Bull, 2013). This particular reference regards the arrival of the voyager, who is interested in authenticity and maybe spending more time than an average tourist in order to explore and discover new places (see the definition for gentritourist). This way of travelling has become more and more popular in the last decade, especially as the younger generations have understood that there are so many opportunities to visit places ‘on a budget’. Going to popular museums or only visiting famous touristic attractions, or eating the globalised version of the ‘local dishes’, are not part of a voyager’s typical experience. Voyagers are more likely to treat the place with respect, as they want to discover it and experience it as it really is and might eventually be interested in staying and be part of the local community. Therefore the voyager typology is similar to the gentritourist one, as it defined persons who are looking for the community sense, for the artistic vibe, for the cultural scene and are interested in preserving heritage and not damaging the environment, by living sustainably. The gentritourist does not have at its centre an ordinary tourist, but rather one who is looking for the authentic and spending more time than average in new places. As a consequence, he/she is keen on visiting globally while making a difference locally.

It is necessary too to ask why ‘gentritourists’ would be so interested in staying in a new place that also presents new challenges? To understand this, the impact of technology and digitalization cannot be ignored, as we are living in an era of internet, which has brought ‘city branding’ to another level due to social media. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Tumblr, Pinterest among others have upgraded cities from ordinary to ‘hidden treasures’ that must be discovered by new users. The advertisement and marketing conducted through the social media platforms is all the more brilliant, as it is free to access and can be very convincing. Typically, the ones managing this marketing are precisely the ones who have been there and are sharing their own experiences, therefore they are more credible for future visitors. But is it just the social media the one which has drawn more people from all corners of the world to certain places at certain times? Another reason for the mass visiting and travelling movement of young generations, identified as voyagers and sometimes ’gentritourists’, is the existence of the multiple low cost airlines flying to key destinations, considered universally worth visiting. Most of the places promoted by low-cost airlines are very popular mass tourism destinations, so probably not the best approach if you are an unconventional visitor or a gentritourist and you are looking for something special or unique to visit. So how do voyagers travel ‘on a budget’ to less accessible, exotic, extreme or rather culturally closed places? Hence, the concept of networking appears in the equation as it is a key factor, because networking is not only present on social media platforms, but also on travel and hosting platforms like Couchsurfing, Airbnb 1 and Gomore [Image 3.]. All these relatively new ways of finding a ride, a travel buddy or a couch to sleep on are opening new dimensions of across borders free socializing and the opportunity of experiencing places as a local. It is considerably easier and cheap to travel with a network of internationally open-minded people and being offered free accommodation through Couchsurfing, for the exchange of cultural experience, and it is even possible to get from A to B for more or less nothing, through hitchhiking or car sharing.The movement of young people all over the world in the search of new adventures or places to live in is directly connected to social media, an international network, low-cost transportation and the desire to live sustainably.

3. “Tourist, traveller, voyager”

The illustration portraits the tourist, the traveller and the voyager (from left to right) as the types of visitors and the sort of places and experiences they are looking for when visiting. The people displayed in the illustration have merely the role to put an image to the written description present in the text and they are free to interpretation.

By understanding how global tourism, gentrification and gentritourism are shaping the urban spaces and creating patterns regarding the way people worldwide live within communities and travel, we can identify the gentritourist as an actor in the middle of these processes.

Therefore neither global or local should be looked at individually, but rather together as the industry of tourism is constantly changing. Tourism as a mass industry has had and still has many negative aspects and it seems fair that since man took, man should give back [Image 4.]. Building on this idea, there is a cycle inside the concept of tourism and visiting, which says that if tourists created a problem in the places visited, a new approach should be adopted to visiting – a flexible and sustainable tourism, one that does not encourage the negative side effects of gentrification. Since mass tourism mainly focuses on globalizing and industrializing local values and increasing costs in order to make more profit, hope might lie within ‘gentritourists’ or voyagers, due to their support of ecotourism and community-based tourism, as mentioned earlier in the article. One might ask how the ‘gentritourists’ are actually encouraging a better way of visiting places? Some of the answers include not encouraging mass touristic sales (touristic bus guides, commercial souvenir shops, fast-food restaurants, tourism agencies etc), engaging with the locals on amiable terms, sustainable means of transportation, accommodation and car sharing, camping, volunteering, teaching or working and living in certain areas for a while. These are popular manners in which people nowadays are travelling ‘on a budget’ for longer periods of time to different destinations and even living in them. There, they might form communities within which its dwellers share common values and try to offer an identity to ‘lost spaces’ such as places with a bad reputation, abandoned, polluted, industrial or partially destroyed districts in cities. Examples 2 have multiplied in the last few years, which suggests that people are looking for more sustainable ways of travelling and living that do not include damaging local values or imposing global influences. Again, there is such a large variety of cases worldwide in which the gentrification process has ended and the people are already ousted and there is no sign that the district was ever any other way, therefore gentritourism would not be a valid and efficient solution.

4. “Man took, man gives”

The cycle of ‘man took, man gives’ is represented in the illustration, on the one had depicting that some part of the damage upon major cities is due to how visitors treat the destinations and on the other hand what happens if they choose to help. The ‘thumbs down’ and the ‘thumbs up’ (from left to right) symbols aim to show mass tourism and globalization as ‘cons’ and to ‘gentritourism’ and ‘community- based tourism’ as ‘pros’. Source: Authors.

In many places mass tourism has perturbed the community sense the cultural identity, the sense of security, the freedom of movement within cities and the preservation of historical and cultural sites. The cycle of ‘man took, man gives’ can be completed by people recycling the less functional sites within cities and bringing them back to life through local community sense, which is a catalyst as it creates a bond between dwellers, no matter if they are originally from there or just visiting. ‘Gentritourists’ are seeking diverse experiences and connections with places and locals, which is why they are a segment of visitors highly valuable to the future of sustainable tourism. Thus, new and different is attractive for the generation of ‘gentritourists’, even if it is more challenging and demanding, possibly deriving from the nomadic demeanour of mankind’s ancestors. This assumption enables hope regarding the will of people to relocate where the issue is and to try to fix it, instead of erasing the places and forgetting about their meaning.

Notes

1. Regarding Airbnb, it has to be taken into account the fact that it is a platform which allows people all over the world to find accommodation either on short or long term in different locations, as long as the locals are ‘renting out’ either their own homes or some other homes they own. One of the downsides of Airbnb is that it has no selection filter regarding the type of visitor it is accommodating and in many popular destinations, such as Barcelona, it is overcrowding the city because it is an attractor for mostly for mass tourism. In short, Airbnb is one of the factors encouraging city overcrowding. On the other hand, the gentritourist is more likely to be looking for a longer stay, therefore not considerably increasing the number of mass visitors and also he/she is more inclined to use Airbnb in order to get in touch with locals and get a more authentic experience. To conclude, there are two sides of the coin regarding Airbnb and gentritourism is taking into consideration the one which does not encourage city overcrowding or illegal ousting of locals.

2. Examples can include Godsbanen area in Aarhus, Denmark or Park de Ceuvel in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

References

— Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014. [documentary film] Barcelona: Eduardo Chibás. [online] Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kdXcFChRpmI> [Accessed 15 September 2017].

— Bull, C. (2013). Cross-Cultural Urban Design. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, ‘Foreword’ XX-Xxi, ch. 1-8

— Currid, E. (2009). Bohemia as Subculture; “Bohemia” as Industry. Journal of Planning Literature, 23(4), p.372-375.

— Davey, M. (2017). Gentrification, street art and the rise of the developer-sponsored block party. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/oct/05/gentrification-street-art-and-the-rise-of-the-bogus-block-party [Accessed 8 Oct. 2017].

— Gunn, C. A. (1994). Tourism Planning: Basis, Concepts, Cases. New York: Taylor and Francis, p. 5.

— Jameson, F. (2005). Archeologies of the future. London: Verso Books, p. 385.

— Lees, L., Slater, T. and Wyly, E. (2013). Gentrification. Florence: Taylor and Francis, p. XV, XVIII, XIX, 91, 96.

— Ley, D. (1996). The New Middle Class and the Remaking of the Central City. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 15.

— Morris, H. (2017). Europe’s Cities: Gentrification or Ghettoization?. [online] IHT Rendezvous. Available at: https://rendezvous.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/21/europes-cities-gentrification-or-ghettoization/?mcubz=3 [Accessed 8 Oct. 2017].

– Smartcitiesdive.com. (2017). Berlin, Barcelona, and the Struggle Against Gentrification | Smart Cities Dive. [online] Available at: http://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/berlin-barcelona-and-struggle-against-gentrification/245126/ [Accessed 8 Oct. 2017].

– Spaces, P. (2017). What is Placemaking? – Project for Public Spaces. [online] Project for Public Spaces. Available at: https://www.pps.org/reference/what_is_placemaking/ [Accessed 10 Oct. 2017].

+

NB: The work presented here is an attempt to reinterpret the process of gentrification and highlight positive aspects of it upon the city. Its aim is to point towards possible innovative solutions and draw a parallel between a contemporary issue and tourism, as travelling is a leisure activity which is likely to attract interested users, who can make a positive change.

Cristina Roxana Lazăr is a freshly graduate of urban design (MSc) from Aalborg University in Denmark and urban planner (BA) from Bucharest University. Her work emphasizes how positive impacts can be planned and generated through the use of tactical urbanism, people-oriented strategies, urban catalysis, place-making and relation user-space theories. Moreover, she is passionate about art and collage rendering and through her work tries to bring a creative and practical perspective upon urban spaces and contemporary ways to design them.

Elisa Diogo Silva is a young architect (MA) and a recent graduate in urban design (MSc) from Aalborg University in Denmark. She has a flair for mobilities design, creating spaces with and for people, sustainable urban developments, and for instigating future urban scenarios. Furthermore, she is passionate about strategic urban developments, democratic design, and the relationship between people, physical settings and less-material occurrences taking place in the urban milieu.

Volume 2, no. 1 Spring 2019