Curating capital: tourism, sustainability, and opportunity in Iceland

– Danielle S. Willkens

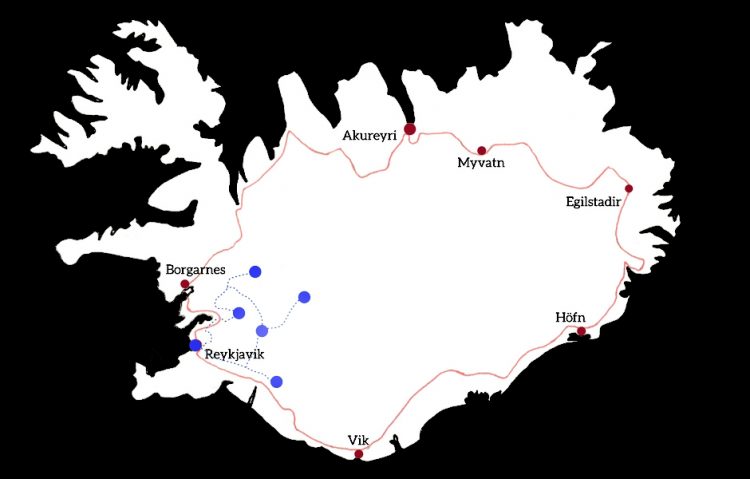

In 2016 and 2017, there were more Americans in Iceland than Icelanders. With a population of a nearly 333,000, and more than 65% living in the capital region, the number of annual visitors to the island have outnumbered the meager Icelandic population since 2003 (National Statistical Institute of Iceland). After the economic crash of 2008 crippled the northernmost capital in the world, Iceland invested in an ambitious tourism campaign (Mathiesen, 2014). Less than a decade later, they are experiencing both financial gains and ecological losses. Now, the island finds itself at an economic and environmental precipice. In 2015, annual visitor numbers surpassed the one-million mark and due to the continuing, hyperbolic increase in visitors, more than two million traveled to Iceland in 2017 1 [Image 1.]. Tourists, typically staying less than four days, arrive by fossil fuel-powered airplanes and cruise ships to partake in the two main tourist routes: the geographical loop around the island’s Ring Road and the manmade circuit connecting several natural wonders in the southwest known as the Golden Circle 2 [Image 2.]. Since Iceland is roughly the same area as Cuba or the state of Kentucky, with nearly 40% of the island covered by the severe terrain of the inland Highlands, the vast majority of tourists traverse the island’s perimeter and entirely overwhelm the capital region, raising essential questions about preservation and resource scarcity [Image 3.].

1. A graph illustrating the steady population growth in contrast to the surging visitor numbers in Iceland.

2. A map of the major cities and sites in Iceland, with the Golden Circle route highlighted in blue and the Ring Road in red.

3. A panoramic view of Reykjavík’s harbor from a UAV (drone), with the growing capital city in the distance.

As a nation, Iceland can be defined, physically and experientially, by the dichotomies of geological time: slow and sweeping glacial movements in contrast to capricious, volcanic eruptions. The natural wonders that tourists seek on the island were created over the course of millennia, yet the influx of tourists in the last decade may cause catastrophic losses at a scale historically comparable to the eruption of Eldfell on Iceland’s southernmost island of Vestmannaeyjar in 1973. Lava engulfed the east side of the island and flowed into the town of Heimaey, barely avoiding the harbor. In addition to radically changing the physical form and composition of the island, the eruption destroyed residences, a historic stave church, and essential infrastructure for transportation, water treatment, fish processing, and power.

The recent, overwhelming numbers of visitors to Iceland are threatening to become the capital region’s 21st century lava: arriving in a constant flow, interrupting quotidian operations, and causing reactionary development that both stresses natural resources and puts historic, vernacular structures at risk due to the influx of cranes and developers that are looking to densify the urban center [Image 4.]. With tourism increasing at such a rapid pace, Iceland may soon find that the loss of natural and cultural capital will far outweigh the benefits of touristic consumerism. Therefore, a wholly sustainable approach to tourism that assesses impacts on society, economy, and the environment, built and natural, will be integral to the future of the island.

4. A view of the Reykjavík’s construction, dwarfing the structures of the historic core, as seen from the island of Viðey.

Historical Perspectives on Tourism in Iceland

In the last decade, low cost, and even free layovers between North America and Europe provided by companies such as the Icelandic-owned WOWair have exponentially increased tourism and the island has become a desirable filming location for popular culture, ranging from music videos by Justin Bieber to the dramatic landscapes of several films such as A View to Kill (1985), Tomb Raider (2001), Die Another Day (2002), Batman Begins (2005), Stardust (2007), and the cult serials such as Fortitude and Game of Thrones.

Since 2013, tourism has been the main stream of revenue for the island. The majority of foreign travelers to Iceland state that ‘nature exploration’ is the main goal for their journey and this aligns with the motivations of Iceland’s first recorded foreign ‘tourists’ who descended upon the island in the 18th century (Houck, 2016). Sites such as Þingvellir National Park, located a short drive from the capital, offer tourists the unmatched opportunity to walk, snorkel, or even dive between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates and, throughout the island, visitors find themselves surrounded by lunar landscapes, powerful waterfalls, glacial planes, and pervasive plumes of steam from thermal fields that inspired the 9th century settlers to call their new home the “smoky bay”, or Reykjavík [Image 5.].

5. A view of Þingvellir National Park.

The possibilities for independent tourism and exploration around much of Iceland are fairly recent developments: the portion of the Ring Road connecting the capital and Höfn, a town east of the nation’s largest glacier, was only completed in 1974. Therefore, visitors to the black sand beaches or basalt formations of Vík on the southern portion of the island once had to travel clockwise around three-quarters of the nation’s perimeter to reach the site. In 2017, however, the nearly 600 residents of Vík saw more than a million visitors pass through their community. In addition to natural sites, Vík is also now home to the largest hotels in the region and one of the busiest fuel stations in the entire nation (Icelandic Tourist Board). Nearly 25,000 rental cars now traverse the island’s roads in the peak, summer season; a stark change from the 1980s when travel was complicated by the fact that road between Reykjavík and the international airport (KEF) was the only thoroughfare paved with asphalt.

Challenges to Natural and Cultural Capital

Beyond the growing stresses on the capital region, the unique geography and dispersal of both residents and resources around the perimeter of the island means that Iceland functions as an interconnected system. The recent surge in tourism is taxing this system, pushing essential elements of infrastructure to their limits: housing, food security, and waste management. Furthermore, the ecological footprint of tourism in the nation challenges the sustainability of increasing visitor numbers. For much of the 20th century, aside from the influx of servicemen stationed at the critical refueling point in the Atlantic during World War II, Iceland was able to operate as a largely self-sustaining entity in terms of food production and energy needs.

The 2010 documentary The Future of Hope further highlighted some of the environmental and infrastructural issues at hand in Iceland. The new projects needed to support eco-tourism are numerous, ranging from visitor centers to service stations and bathrooms on the Ring Road and in National Parks. Although Iceland has plentiful, renewable energy, the majority of construction materials will need to be imported and the ‘light touch’ employed for the paths and barriers at natural sites may no longer work with increased visitor numbers: at Þingvellir National Park, alone, visitor numbers have increased 80% in the last decade. As Iceland continues to promote ecotourism, local authorities are rushing to construct barriers for protecting tourists and natural resources alike: waterfalls, cliffs, and thermal fields pose dangers to curious visitors who wander from prescribed routes, site erosion runs rampant, and ecologists are carefully monitoring water and soil quality [Image 6.].

6. A handmade cautionary sign at the geothermal fields of Mývatn in northern Iceland. © archDSW

The eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010, which impacted air travel for more than twenty countries and 10 million travelers, put Iceland’s food crisis in the spotlight and ongoing tremors at the more powerful volcano, Kalta, raise key questions about the sustainability of tourism. A major eruption, or even a significant event at one of the other twenty-eight active volcanoes, would result in impacts on air quality could cripple a nation that feeds its inhabitants and visitors primarily with imported goods. The slow food movement is taking hold, with the construction of greenhouses powered by geothermal energy, but it has yet to reach a balance between the scales of production and consumption [Image 7.].

7. Greenhouses like this one at Hveragerði, powered by the nation’s ample geothermal energy, are being constructed around the island to address the nation’s food security issues. © archDSW

Lessons from sites such as Venice illustrate the crippling impacts of a transient population: when tourists outnumber residents and there are more gift shops than schools or playgrounds, once dynamic and rich heritage sites can feel highly curated and even Disney-fied. Can a place retain its significance and identity when there are no locals? Proposed regulations for Airbnb hosts in Iceland directly address this question: hosts must register with the government, pay VAT, and remunerate business taxes for properties rented longer than ninety days a year.

Moving Forward: Reactions and Regulations

In response to the demands imposed by escalating visitor numbers, the Tourist Site Protection Fund was established in 2011 (Þorleifsdóttir, 2016). The fund is currently working with 450 sites around the island, but their impact has been limited due to the requirement that localities provide 50% of project funding. In the 21st century, the tourist conundrum in Iceland is twofold. Firstly, Iceland will need to adapt to maintain its close-loop self-sufficiency that is now burdened by a surge in energy demands from the influx of ecological adventurers who require housing and food as well as fortified infrastructure to support both travel and telecommunications. Secondly, Iceland needs a new tourism campaign that moves away from the purported eco-tourism that is resulting in more harm than conservation.

As one of the three Icelandic projects in Irving’s 1001 Buildings You Must See Before You Die, the Bláa Lónið [the Blue Lagoon] is located in a lava-formed moonscape near Grindavík, about thirty miles from Reykjavík, and it is estimated that 90% of Iceland’s foreign visitors bath in the waters here (Irving, 2007) [Image 8.]. Since the mid-1970s, a geothermal power plant called the region adjacent to Svartsengí home and locals used the warm, silica-filled pools, a natural byproduct of the power plant, for restorative bathing. However, a formal architectural initiative that harnessed the naturally dynamic environmental conditions to promote health, relaxation, and commercial enterprise was not launched until the 1990s. This initiative relocated and manicured elements of the pools and in 1999, Vinnustofa Architects designed a comprehensive, spa-inspired complex featuring showers, a café, and steam rooms. In the last decade, BASALT Architects’ founder, Sigríður Sigþórsdóttir, and Design Group Italia joined the project and, subsequently, the site welcomed in-pool bars, for both facials and beverages, as well as an upscale restaurant. Catering to the abundance of foreign visitors, another major addition is now underway: the new hotel, restaurant, and spa facilitates are slated to open in 2018.

8. A panoramic view of the Blue Lagoon from a drone, showing the original geothermal plant on the far right and the new construction at the spa complex on the left.

In Iceland, sundlaugs [public geothermal pools] are as common as grocery stores or parish churches, thereby forming an essential element of the nation’s holistic sense of community and well-being. The island’s most famous geothermal pool, however, is not a site where visitors and locals mix. Unlike entry to the local pools of Reykjavík, granted as part of the capital regions’ bus pass system, or other municipalities that charge menial entrance fees, often based on the honor system, the Blue Lagoon is a pricey and highly choreographed construction. The entrance is a dramatic slice through volcanic stone and the luminescent blue water reflects the surrounding landscape that is a well-integrated blend of the natural and manmade: the finished concrete even used crushed lava for aggregate. The released steam of the power plant’s cooling towers blends into the mist rising from the pools, making visible the geothermal power that has been powering the region since the 1930s and is so plentiful that the capital’s sidewalks are embedded with radiant heating coils to melt snow. Despite the dramatic surroundings and careful, refined material palette of the architecture, the Blue Lagoon’s alluring landscape is marred by massive parking lot filled with buses and rental cars. It is an environmentally responsive project, and economically prosperous, but the projects lacks the third vein of the holistic sustainability model: society. As an all-in-one venture with lodging, restaurants, and even coordinated transportation to and from the airport, many visitors to the Blue Lagoon do not explore the surrounding region, spending money at local, smaller businesses. The new business model for the site’s expansion is even more alarming from the standpoint of carbon footprints: a quick flight and direct transportation to the site can make a luxurious spa weekend.

In response to the popularity of the Blue Lagoon, the Tourist Board plans to extend the promotion of water-based tourism by leveraging existing resources such as hot pots, community geothermal pools, and boating opportunities. Overall, however, these campaigns are reactionary and not preventative. At the present moment, Reykjavík and the dynamic systems of Iceland’s natural landscape are susceptible to the same form of entropy that has plagued Barcelona, Dubrovnik, and other heritage sites around the world. Additionally, the mass of visitors, largely concentrated in the capital region, are testing the generally accepted tenet that everyone who lives on the island should serve as a ‘host’ for foreigners. In Reykjavík, this symbiotic relationship is particularly overtaxed since locals are quickly realizing the extent to which their public spaces and services must be shared with visitors.

Officials from the Icelandic Tourist Board are now finding themselves running unprecedented site interpretation courses for park stewards, based on training materials from the U.S.’s National Park Service, and encouraging ‘slow tourism’, a concept counter to the current bucket list ‘sprint’ of Icelandic layover packages. By encouraging people to stay longer and explore farther afield, the Tourist Board hopes that the strain on certain sites in the capital region and south Iceland will be reduced and that visitors will be dispersed more evenly around the island. For example, less than a quarter of visitors to the island make their way to the West Fjords, but improvements in roads and junctions for cars, buses, and bikes, as well as investments in small town initiatives may change this, allowing visitors to explore farther and with a broader scope of curiosity for the nation, its history, and the intriguing relationships Icelanders have cultivated between the built and natural environments.

Opportunities for 66 North: The Future of [Architectural] Tourism in Iceland

In the only comprehensive guidebook on Icelandic architecture, published in both English and Icelandic by one of the nation’s only architectural historians, Pétur H. Ármannsson, it is stated that “architecture is often ranked as a rather insignificant part of Icelandic culture” (Ármannsson, 2011). Yet, the examples of urban and rural vernacular architecture as well as the state-sponsored structures from the 20th century and exuberant modernists churches that dot the landscape are worthy of touristic and scholarly attention [Image 9.]. Many of these structures successfully mitigate, and even celebrate, the abrasive climate and atmospheric chiaroscuro associated with life above the 66th parallel north of the equator, especially through the use of a volcanic rock found throughout the earth’s core and Iceland’s surreal lunar landscapes: basalt. Additionally, the promotion of Iceland’s architectural capital may offer architectural historians essential leverage through cultural heritage tourism that may curb problematic development and make a scientific case for the protection of significant projects in the built environment due to their embodied energy.

9. In an essay entitled “The Mountains are their Castles”, Ármannsson argues that baðstofa are Iceland’s most important contribution to architectural history. These vernacular constructions were the typical one-room residences for much of rural population in the late 18th and 19th centuries and served the rotating tenant farmers who needed dwellings that could be made quickly with local materials: minimal timber framing, rammed earth and turf layers formed the walls and roofs, and the stretched skins of dried Skate fish were used as translucent coverings for apertures.

With no professional schools of architecture until 2002, Iceland’s built environment was strongly influenced by trends in continental Europe, particularly in Denmark. Once Iceland’s colonial ruler, Denmark transferred executive power to the island via Home Rule in 1904 and Iceland achieved its independence four decades later, identifying the opportunity for autonomous self-government while the Nazi government occupied Denmark. The lack of professional architecture schools on the island did not, however, deter architectural or systemic innovation. In fact, the outsourcing of architectural education may be credited with the unique and responsive qualities of Iceland’s architecture from the late 19th and early 20th centuries: designers learned from Western precedents and basic tectonics abroad but returned to the island to apply these lessons with adaptations to address seismic conditions, material limitations, and climate.

The attentiveness to materials, with reference to their lifespan and experiential qualities, has been entwined with Icelandic architecture since the first century. Prior to initial settlement on the island (c.870-930), approximately 25% of Iceland was forested. Like much of Europe, the Middle Ages in Iceland was characterized by deforestation, with the scant timber supplies depleted for fuel and shipbuilding. By the 12th century, less than 2% of the island was wooded, putting a severe restriction on the use of wood for domestic or civic architecture. Masonry was also impractical: the volcanic soil and porous lava rocks demanded alternative approaches to traditional stone building techniques and the lack of clay made the production of bricks nearly impossible (Ármannsson, 2011). The majority of state sponsored architecture under Danish rule was not a sustainable model either, considering that much of the urban fabric, composed of seemingly utilitarian wood structures weatherproofed in cast iron, and later, aluminum, were actually prefabricated abroad then shipped to Iceland for assembly. The practice of painting the cladding became an Icelandic signature since it reduced the infiltration of rust and provided a colorful palette to contrast the frequently grey skies and brighten the long, dark winters [Image 10.].

10. Examples of Reykjavík’s colorful and eccentric corrugated ‘gingerbread’ architecture.

Since the early 20th century, Iceland has been a model of progressive policy implementation in relation to renewable energy, but as the nation responds to the rapid influx of travelers, the tenets of environmentally responsible architecture and infrastructure need renewed attention. Although there are forty buildings under the care of the National Museum of Iceland, there is no designated architectural curator to manage this historic collection 3 [Image 11.]. For these reasons, the island loses the opportunity to showcase its innovation in the built environment: visitors bypass some of the earliest examples of ‘green’ architecture from the 20th century, such as the preserved transformer stations (1921) by Samúelsson that were constructed in coordination with the groundbreaking hydroelectric facility along the Elliðaár River, and they unknowingly traverse sidewalks embedded with radiant heating coils to melt the winter’s snow, connected to Reykjavík’s pioneering geothermal residential heating districts from the 1930s (Jóhannesson, 2000) [Image 12.]. There are other missed opportunities to put the civic and religious projects of State Architect Guðjón Samúelsson (1887-1950) in conversation with natural sites. More than an architect experimenting with neo-gothic and Art Deco architecture in concrete with the inclusion of sparkling aggregate (obsidian, quartz, and spar), Samúelsson invented a kind of neo-geologic architecture that references the basalt formations surrounded by waterfalls and the black sand beaches that are so popular with foreign tourists [Image 13.].

11. Two of the turf-covered churches under the care of the National Museum of Iceland: the northern Grafarkirkja (b.1765) in Skagafjörður and the southeastern Hofskirkja (c.1883) in Öræfi.

12. A view of one of the neo-Baroque transformers and the downtown construction revealing the radiant heat coils.

13. The tower of Hallgrimskirkja (1938-1986) features prismatic basalt forms but the basalt formations that Samúelsson playfully called ‘elfin citadel’ were reinterpreted as buttresses, presenting the viewer with a façade that seems to grow from the natural summit of Skólavörðuholt and imposingly reach towards the sky.

In the quest to be a model of sustainability and ecotourism, Iceland must protect a key asset of its carbon footprint: the embodied energy and cultural capital of its extant architecture. The island’s tourist-driven development must prioritize the protection of the natural environment but it also must be proactive with respect to the preservation and conservation of an architectural heritage that has not yet received due attention. Between 2000 and 2016 Reykjavík’s population nearly doubled. Demographers predict that this surge will continue through 2030 so the densification of the capital region and improvements to its infrastructure are at the center of the New Municipal Plan (Scarcity in Excess, 2014; Maack, 2015). Without a comprehensive study of Iceland’s architecture, it is hard to imagine that the island’s built heritage, whether individual structures or collective historic districts, will be properly identified for protection from the throng of cranes that are poised to add new hotels and high rises to the capital’s skyline. As the island tries to inaugurate a massive do-no-harm program for ecotourism, bringing services, essential way finding, and landscape architecture interventions to frequently traversed sites, the island is, curiously, doing fairly little to promote its architectural heritage. Increased attention to key precedents in the extant built landscape, however, will provide a way for Iceland to forge a sustainable future that not only continues the tradition of geological architecture parlante but also incorporates an essential, regional approach to materiality and passive design.

Notes

1. The Icelandic Tourist Board is very transparent with their reporting. Annual reports and relevant articles are available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/en.

2. From FERÐAMÁLASTOFA [Tourism in Iceland], report available online http://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Frettamyndir/2016/juni/tourism_-in_iceland_in_figures_may2016.pdf

3. Some, but not all, of these structures are addressed in a recent bilingual series on cultural heritage sites around the island; see Björnsson, B. r. G. (2013a) 18th century stone buildings. Translated by: Yates, A. Reykjavík: Salka. Björnsson, B. r. G. (2013d) Writers’ homes. Translated by: Yates, A. Reykjavik: Salka. Björnsson, B. r. G. (2013c) Turf churches. Translated by: Yates, A. Reykjavík: Salka. Björnsson, B. r. G. (2013b) Large turf houses. Translated by: Yates, A. Reykjavík: Salka.

References

— Ármannsson, P. H. (2011). “The Mountains are their Castles”: Contemporary Architecture and Local traditions in Iceland, in Schmal, P.C. (ed.) Iceland and architecture? Frankfurt: Deutsches Architekturmuseum, pp. 11-45.

— Future of Hope, 2010. Directed by Bateman, H. Iceland: Future of Hope Ltd.

— Björnsson, B. r. G. (2013). 18th century stone buildings. Translated by: Yates, A. Reykjavík: Salka.

— Björnsson, B. r. G. (2013). Large turf houses. Translated by: Yates, A. Reykjavík: Salka.

— Björnsson, B. r. G. (2013). Turf churches. Translated by: Yates, A. Reykjavík: Salka.

— Björnsson, B. r. G. (2013). Writers’ homes. Translated by: Yates, A. Reykjavik: Salka.

— Houck, O. W. (2016). Centering Reykjavik, Imperializing Morris: The viability of Travel Narratives in Architectural and Urban History. M.A. Thesis, University of Virginia [Online] Available at: http://libraprod.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/libra-oa:11587

— Irving, M. (ed.) (2007). 1001 buildings you must see before you die. London: Cassell Illustrated.

— Jóhannesson, D. (2000). A Guide to Icelandic Architecture. Translated by Bernard Scudder. Edited by Jóhannesson D. Reykjavík: Association of Icelandic Architects.

— Maack, S. (2015) ‘Can Reykjavík Stop the Sprawl? A look at Reykjavík’s new municipal plan for 2010-2030’, HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland], 1, pp. 42-49.

— Mathiesen, A., Zaccariotto, G. and Forget, T. (eds.) (2014). Scarcity in Excess: The Built Environment and the Economic Crisis in Iceland. New York, NY: Actar.

— Norðfjörð, B. (2015). Hollywood does Iceland: authenticity, genericity, and the picturesque. Films on Ice Cinemas of the Arctic. Edinburgh University Press, pp. 176-186.

— Þorleifsdóttir, S. (2015) Growing Pains: designing travel destinations in Iceland. HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland], 2, pp. 86-97.

Dr. Danielle S. Willkens, Associate AIA, FRSA, LEED AP BD+C, has practice experiences in design/build, public installations, heritage documentation, and extensive archival work in several countries. Willkens was the Project Manager for the Learning Barge, the University of Virginia’s innovative design/build project for a floating classroom and sustainable field station on the Elizabeth River. Most recently, she was the recipient of the Society of Architectural Historians’ H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. Between June 2016 and May 2017, she traveled to Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Cuba, and Japan to research the impact of tourism on cultural heritage sites. Building on time as a historical interpreter at Monticello and a Sir John Soane Museum Travelling Fellow, she pursed a PhD at UCL’s Bartlett School of Architecture and her manuscript is in development for publication with the University of Virginia Press: The Transatlantic Design Network: Jefferson, Soane, and agents of architectural exchange, 1768-1838.

Volume 2, no. 1 Spring 2019