Tourism in transformation: from a hectic urban environment to urban resilience in Barcelona

– Elisa Diogo Andrade Silva & Cristina Roxana Lazăr

The tourism industry has been growing worldwide since the first decades of the 20th century (Sezgin & Yolal, 2012), but particularly over the past six decades (UNWTO, 2017a). Since then, although variable in time and according to geographical location, the main reasons for its development are the improved transportation technology, growing wealth, and the advent of tour operators with package tours (Sezgin & Yolal, 2012). In most recent decades, the popularization of previously elitist means of transport like aeroplanes with the emergence of low-cost airlines (Theng, Qiong & Tatar, 2015) along with online information, online experience sharing, and social media (Zeng, 2013) have strongly contributed to the increasing number of tourists worldwide. Nowadays, social media networks like Facebook, Twitter or Instagram are essential promotion tools used both by private tourism related companies and by many countries as part of their tourism strategy (Zeng, 2013). Such developments contribute to the continuously increasing numbers of travellers, leading to “an extreme concentration of tourists in one place” in many countries (Theng, Qiong & Tatar, 2015), in other words, to mass tourism (Sezgin & Yolal, 2012; Theng, Qiong & Tatar, 2015). Mass tourism and its inordinate number of tourists are associated with great profits, which in turn can be linked to large investments and development (Theng, Qiong & Tatar, 2015; UNWTO, 2017b). However, it can also be a synonym for great damage as it can lead to inflation, property speculation, and the weakening of local businesses and activities by the insertion of global and mass businesses on a large scale, leading to substantial levels of exclusion (Theng, Qiong & Tatar, 2015:2). Palma de Mallorca, Venice, Dubrovnik and Barcelona are some examples of cities that, over time, have been affected by mass tourism (Hunt, 2017; Kettle, 2017).

For several decades now, many European and highly touristic cities such as London, Barcelona, Paris, and Berlin, among others, have been subjected to gentrification practices most of which are covered by urban renovation processes. In Barcelona, this article’s case study, the 1992 Olympic Games were the kick-start of a renovation, branding and gentrification procedure that lasted for decades (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014). Following primarly the same formula, the gentrification process boils down to: “first come the artists, then the cranes. As the kamikaze pilots of urban renewal, wherever the creatives go, developers will follow, rents will rise, the artists will move on, and the pre-existing community will be kicked out with them.” (Wainwright, 2016). After gradually ousting most of its residents and local commerce, the renovated and attractively located places are now accessible and appeal to tourists and to stronger economical classes. Municipalities realize the great economic impact tourism has in city development therefore; they foster measures that show a lively and attractive city. Cities end up being ‘programmed’ and developed according to tourists’ needs, in other words, they end up being the result of a touristic monoculture. Of course citizens also enjoy the benefits of such a striking and dynamic city achieved through tourism development. Increasing job opportunities, better and cleaner public spaces, as well as an increased presence of cultural activities and events, usually follow the tourism boost (Fainstein & Galdstone, 1999). However, locals’ salaries do not necessarily pursue the consequently increased prices. Overstretched public transport infrastructures are followed neither by a re-structuring of the system nor by measures stimulating sustainable mobility such as bicycle infrastructures. The ongoing disappearance of local commerce and its replacement with mass commerce interferes with residents’, merchants’ and travellers’1 experience as well as with site identity.

Mass tourism: The hectic Barcelona

To shape an attractive touristic city, politicians endorse measures that facilitate the gentrification process, which in some cases, like in the former residential sailor’s neighbourhood of La Barceloneta in Barcelona, led to the ousting of most of the area’s dwellers (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014). Those who still live in the district feel threatened by the possibility of having to leave the neighbourhood that saw them grow up because of the high demand for tourist accommodation. Some [either people or entities], in the pursuit of more attractive economic results, use ‘less conventional’ approaches, that is, inappropriate methods, such as putting waste by their doors and in their corridors, that encourage residents to leave their homes (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014). Then, the owner uses the property for tourist facilities obtaining greater profit. In most cases, authorities do not take action against such situations, although it is known that a lot of touristic accommodation is illegal (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014). Others see their rents increasing gradually, thus being forced to move to a more affordable housing situation, leaving their district, neighbours and the story they built together throughout the years. These acts deeply affect people’s lives, making them change their living situation against their will. Consequently, such facts have led and still lead inhabitants to protest and demonstrate displeasure towards tourists, generating a hostile environment between them. Thus, Barcelona is not only a knot of numerous historical monuments, renowned architecture, attractive beaches, a unique vibe and atmosphere, and a pleasant climate, it is also a congested city and a territory of conflict between residents’ and tourists’ individual behaviour and interests. This too ends up being reflected in Barcelona’s public space and living environment [Image 1.].

1. Mapping the touristic Barcelona – mapping the congested touristic city and the atmosphere lived within it. Source: Authors.

La Barceloneta is now one of the most popular and touristic barrios (Spanish term for districts) of the city. Throughout the years, the implementation of several tourist accommodation facilities in the neighbourhood along with some of the urban interventions that followed, have contributed to its popularization. The urban renovation of Plaza del Mar and the urban intervention and extension of the Maritime promenade up to the popular W Hotel, which included adjustments to the barrio’s transit spaces and functioning, have transformed La Barceloneta coastline (Angulo & Muñoz, 2009). Some of the many questions one may ask about the district are: ‘What is the current urban character and identity of this neighbourhood?’, ‘Is it an exclusive enclave for tourists?’, ‘Did the barrio’s dwellers gain anything from the urban interventions?’ On a broader scale, a lively and appealing urban area integrated in the city’s urban fabric is positive for both the city and its residents. Yet, the neighbourhood’s inhabitants are not the ones using the space the most, since many of them do not live there anymore, and the ones who do, do not see themselves reflected nor represented in the barrio’s new identity. La Barceloneta’s urban renovation did not bring users and the built environment any closer; on the contrary, it created a gap between them.

Participatory processes aim for sustainable proposals in which both users and stakeholders are given a voice and their interests are taken into account in order to bond users and the built environment, however, they do not assure such sustainable solutions (Jones, Petrescu & Till, 2005). Through participatory practises, the gap between the built environment as it is and the users’ desired built environment becomes smaller. “Participation effectively addresses this gap through involving the user in the early stages of architectural production, leading to an environment that not only has a sense of ownership but is also more responsive to change” (Jones, Petrescu & Till, 2005:xiv). Thus, a collaborative urban process aiming a democratic urban solution gathering both housing for residents and a lower and controlled amount of tourist accommodation could have been a solution for La Barceloneta urban renovation process. Consequently, a higher quality of life for the barrio’s inhabitants along with a higher sense of ownership through empowering its residents would have been presented while a more authentic experience and stay for tourists would have been assured. Such a solution would have helped preserving or re-creating an identity based on meaningful experiences among dwellers and visitors. Moreover, according to Klingmann (2007), respecting the heterogeneity of the place while promoting cultural values to build a sustainable identity, are necessary to build successful branding strategies.

Public space as the social open space that serves the countless and diverse citizens’ daily needs is no longer serving its full purpose. Mass tourism is distressing people’s daily mobility, diminishing [some] people’s equal right to use the public space and disturbing the platform that Cattell (2008) defines as the result of humans meaningful experiences and actions over time (Chitrakar, 2016). Much of Barcelona’s public space, either a narrow sidewalk, a promenade, a park or a square, is usually overcrowded with tourists hampering its use. Large groups of tourists, standing in queues that last the entire day, occupy the public space surrounding La Sagrada Família (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014). A place once used by locals on lunch breaks for instance or by daily commuters on their way home is now an avoided path due to how rugged it became. Mass tourism undermines inhabitants’ mobility. Furthermore, dwellers of the surrounding districts no longer see themselves as part of that urban space and simply avoid using it. Is the city’s infrastructure prepared for these intense and drastic changes of use? Are there any urban solutions that can adapt to such changes and maintain the quality of the urban space for both tourists and residents?

The current situation of Park Güell, the world-known public city park designed, like La Sagrada Família, by the architect Antoni Gaudí, is another example of the damage caused by mass tourism. With paid and controlled entrances, the place is more of an amusement park serving tourism necessities. Even with free entrance for the neighbouring residents, few appreciate going for a walk in an overbooked park that before the controlled entrances had an average of 25.000 visitors per day (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014). The vast groups of tourists stopping and gathering at every corner, or taking pictures every second, the large number of buses and taxis accessing the park daily destabilizes inhabitants’ mobility both inside and outside the park perimeter. The number of visitors also raises questions regarding the preservation and protection of what is considered a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. In this particular case, one may advocate that mass tourism is damaging what is declared as having universal cultural value.

Mercat de Sant Josep, commonly known as La Boqueria, an extremely important public market situated in the popular La Rambla, is also suffering from mass tourism (NPR, 2017). A commercial public space intrinsic and so representative of the lifestyle, culture and atmosphere of the city that has been serving Barcelona’s citizens and visitors for over a century, is today more of a ‘theme park’. With daily and mostly overcrowded passages, visitors who aim to use the space according to its real function are unable to circulate and buy groceries within such a congested space. As a consequence, in 2015 the market restricted access on Fridays and Saturdays for groups of 15 people or more until a certain hour so that it could respond to city’s residents’ needs and operate with less mishaps (Barcelona Metropolitan, 2015). Are schedule restrictions the permanent solution or simply a temporary one? Should urban spaces be treated like entertainment parks? Are physical barriers the answer to manage overcrowded spaces? If so, then the public space will end up being a fragmented framework of urban life, restricted by several obstacles where people move from A to B unaware of their surroundings searching for the so fantasised experience that branded places like the above-mentioned ones promise. Meanwhile, the ‘life in-between’, both material and the less-material occurrences that arise in the remaining public urban spaces end up being damaged or ignored [Image 2.].

2. The crowded city – illustrating the lack of awareness about the city caused by overcrowded public spaces and over-branded elements of the city that ensure a precise experience leaving no room for the unexpected or for enjoying the ‘in-between’. Source: Authors.

Mass tourism, by producing congested spaces like the surroundings of La Sagrada Família, Park Guëll and its adjacent transit infrastructure, and La Boqueria, is responsible for residents’ tendency to avoid them whenever possible. Moreover, Barcelona achieved considerable homogeneity due to a substantial replacement of local businesses with mass commerce businesses and to a standardization of touristic offers where local or unique experiences are rarely lived. As already mused by Barcelona’s municipality, the standardization of the city’s touristic experience, and the drawbacks related with it, could be the basis of Barcelona’s degradation (Goodwin, 2016). Consequently, travellers end up experiencing a scenario that lacks authenticity, and city inhabitants do not see themselves reflected in their city’s public space, and feel a reduction of rights regarding the use of public space, whilst their urban mobility has become quite damaged.

An alternative to mass tourism: Building a resilient Barcelona.

In order to uphold Barcelona as an open and great tourist destination, to empower its citizens, and to increase the city’s quality of life for both dwellers and visitors (Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2017b), a different approach towards tourism development must be considered and executed. The concept of sustainable tourism is an alternative to mass tourism as it aims to be an element integrated in regional developments (ETE, 2018) and not simply be seen as a profitable industry by itself. According to the ETE – Ecological Tourism in Europe (2018), sustainable tourism development bases itself in ecological sustainability, social equity and adaptation to local cultures, and economic sustainability. In other words, sustainable tourism development intends to protect the local natural environment by respecting its fragilities, wishes for a stable development considering locals’ and stakeholders’ interests by allowing both to participate in the development strategy, and desires a strong economic cycle in which the community is the one benefiting the most from tourism profits.

Barcelona’s municipality has already taken some measures in relation to tourism management. According to Goodwin (2016), Barcelona has drawn up sustainable development plans for the city and its tourism in order to improve its management and mediate the damages caused by mass-tourism. The ‘Barcelona Strategic Tourism Plan for 2020’ made by the municipality, very succinctly aims to enrich the city’s tourism by 2020 using sustainable measures. The last two years were spent detecting problems, gathering data, conducting studies, working with and meeting different stakeholders, and analysing possible strategies. It was in 2017 that the project began to put some of its plans into action. A multidisciplinary team aims, based on a participatory diagnosis, to manage tourism through categories established by them, such as ‘Governance’, ‘Knowledge’, ‘Destination Barcelona’, ‘Mobility’, ‘Accommodation’, ‘Managing Spaces’, ‘Economic Development’, ‘Communication and welcome’, ‘Taxes and Funding’, and finally ‘ Regulation and Planning’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2017a).

Another initiative created by the municipality that encourages city development through participatory processes is the project ‘decidim.barcelona’, a digital and online platform that creates and organizes projects in action [as well as future ones] in order to ‘build a more open, transparent and collaborative city’ (decidim.barcelona, 2018). ‘Decidim.barcelona’ is a participation instrument that gives a voice to all citizens interested in cooperating with the municipality towards the improvement of their city through various collaborative projects. It also offers the possibility to follow their development. Thus, it becomes a collective platform for both city makers, who aim to maintain Barcelona as a touristic city, and citizens, who want to reclaim their city, contributing to the sustainable development of Barcelona. The platform comprises both less elaborated projects and long-term and more striking ones like ‘Les Rambles’ initiated in November 2017. The initiative relies on a collaborative process between the municipality, citizens, local entities and the specialist team km-ZERO to jointly analyse the existing issues of the tourist zone La Rambla and rethink its public space for a better adaption to current and future needs (decidim.barcelona, 2018). How to manage spaces of great affluence, how to improve the public transport and accessibility and how to enhance the citizens’ use of space while mediating tourist activities are some of the project’s points of discussion (COAC, 2017). The project is structured in three main phases: phase 0 is the presentation of the project and establishment of groups of work, phase 1 is the collaborative analysis and diagnosis stage, phase 2 is the co-production of proposals for the redevelopment of La Rambla based on remarks from the previous stage. For the final phase, a project shall be selected to be initiated on June 19, 2018. Throughout the process, there will be four open workshops, two participatory diagnoses, and two more meetings for the co-production of proposals that citizens are invited to take part in. Having the co-operative meetings as starting points, the ‘Citizen Cooperative Groups’ composed of citizenship specialists, representatives of the different stakeholders, and km-ZERO, are in charge of developing the process (decidim.barcelona, 2018).

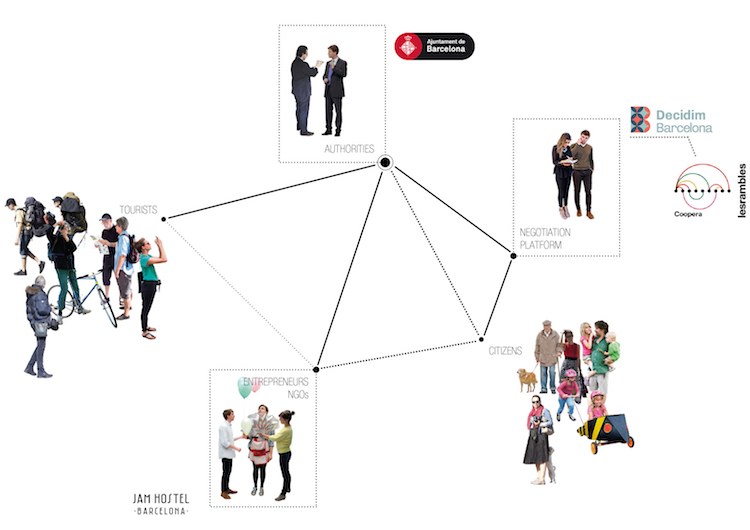

There are also independent and smaller scale projects, like the JAM Hostel Barcelona (JAM Hostel Barcelona, 2017), which aim at and contribute to producing a more sustainable city. It is more than tourist accommodation; it is a sustainable project in itself promoting responsible tourism, among many other sustainable conducts, located in a less congested district of Barcelona, Gràcia. They encourage sustainable mobility like walking and biking by providing free and safe bicycle parking, consequently generating a minor impact on the city. Through inviting visitors to discover less touristic spots of the city by not offering the traditional touristic maps and through inspiring guests to consume local and authentic products and food by promoting the neighbouring commerce stores and by serving local organic products themselves, they believe their visitors create a lower impact in the city (JAM Hostel Barcelona, 2017). JAM Hostel Barcelona, can also be seen as a balancing negotiator between citizens and tourists. By rejecting all kinds of activities related with mass-tourism like group tours or pub-crawls, and instead offering an alternative experience to its visitors (JAM Hostel Barcelona, 2017), it warns them about the damage of mass-tourism, encouraging responsible tourism behaviour. Consequently, by contributing to lower impact tourism, it at the same time enhances and improves citizens’ urban daily life. Balancing both interests also meets the objectives promoted by Barcelona’s municipality. In this way, projects like JAM Hostel Barcelona should be strongly endorsed and economically supported by the authorities for their contribution and ecological footprint. A strong and collaborative relationship between the different stakeholders as well as a well-deserved support to initiatives that contribute to the municipality’s campaigns can be decisive in creating a healthier tourist city [Image 3.].

3. The interplay between Barcelona’s stakeholders and actors – Barcelona Municipality, as the main organization embodies both citizens and tourists interests. decidim.barcelona, as a negotiation platform created by the authorities allows citizens to represent themselves. Authorities should also support initiatives like ‘JAM Hostel Barcelona’ that promote Barcelona as a tourist destination while contributing to citizens’ quality of life. Source: Authors.

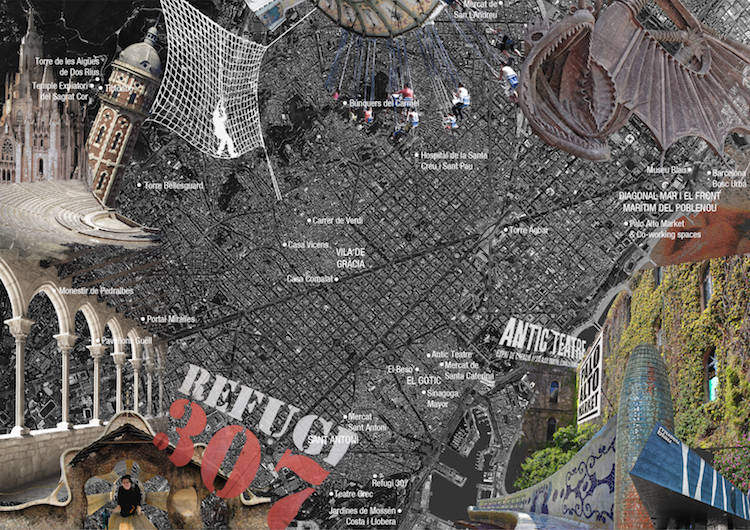

An instrument that could also contribute to sustainable tourism would be the development of less traditional physical and digital tourist maps. Maps are tools commonly used by tourists that end-up influencing one’s destinations, tours, visits and focus. At the same time, maps are ordinary representation tools amongst architects, urban designers and planners, which in turn are among the people that know a city the best, from its cultural secrets, its architectural veiled treasures, to its various and less-material prevailing atmospheres. Accordingly, less conventional tourist maps could emerge illustrating for instance some hidden gems of the city [Image 4.], or route maps suggesting many alternative walking and biking routes including several stops in local stores to taste different and authentic gastronomic delicacies, or perhaps make the map a game, a kind of a treasure hunt for those who travel with children. Such less typical mappings could be the invitation for many tourists to get to know the city while avoiding the packed places. Inviting visitors to explore less touristic locations of the city and its surroundings, suggesting them to choose sustainable tourist accommodation, inspiring them to try local and authentic products according to their own interests, as well as discouraging them from a ‘tapas tour’ and globalized restaurant chains, can avoid the congestion of certain spaces.

The municipality of Barcelona, as the main stakeholder interested in managing the city’s public space for tourists and citizens, could launch mapping challenges with various themes serving different tourist interests. Supporting and nurturing such projects, and discouraging projects devoted to mass tourism, would not only disseminate the presence of tourists in the city, relieving overfilled areas, but also would attract investors, creatives, and entrepreneurs to develop projects with a similar mind-set.

Conclusion

Since the Olympic Games in 1992, Barcelona has successfully promoted its vibrant, creative, cultural, and tourist welcoming character, however, never was the city prepared for such an outcome. In the process of making Barcelona attractive in touristic terms, some citizens lost their homes and neighbourhood relationships, others their local businesses, and others felt they have lost the right to use the public space in their own city (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014) as the city became overcrowded with tourists. The consequence of such events led and still leads to frequent protests, some angry action like writing on city’s walls ‘tourists are not welcome’ or ‘tourist you are the terrorist’ [Image 1.], creating a unfriendly environment between dwellers and tourists. It can be stated that in Barcelona, the tourism monoculture development led to poor and unsatisfactory solutions such as implementing gates or time restrictions, illustrating the lack of social consideration and holistic urban thinking in the process. Currently, steps are being taken to manage the high number of tourists, to bring the city back to its citizens, to heal from mass-tourism injuries, and remain one of the top touristic destinations. Barcelona is in a transformation process trying to move away from a disturbing tourism to a healthy and sustainable one by introducing measures based in sustainable tourism development that better respond to different users and future needs. Barcelona aims to create a more resilient and flexible urban environment that reflects the occurrences that take place between citizens and tourists while meeting their daily needs. Additionally, citizens, city makers, entrepreneurs and others must be actively invited to bring forth sustainable projects, and primarily, must be greatly supported in economic terms when implementing them. Nonetheless, these efforts come at a high price, take a considerable amount of time, and involve a high level of dedication.

Even with the prominent cases of cities injured by mass tourism such as Barcelona, Venice or Dubrovnik (Hunt, 2017; Kettle, 2017), dangerous gentrification practices and monoculture branding processes still terrorize some cities and ignore the collateral damage caused by mass tourism. Branding and tourism strategies should not only respond to the immediate needs of promoting cities and their cultural, historical, bohemian and architectural [among others] values; they should also anticipate adverse outcomes and possible solutions for them. Thus, it is urgent to adopt participatory processes in the development of cities to balance the interests of locals and tourists in order to reach a set of sustainable and resilient solutions to address upcoming needs [Image 3.]. As stated by Jaume Collboni, the Second Deputy Mayor of Barcelona, “Tourism has to serve the city and not the other way around” (Goodwin, 2016). By examining Barcelona as a case study, some dangerous consequences may be avoided in other cities; in particular the ones presently undergoing a gentrification process, like Lisbon or Oporto (Sampaio, 2017). Moreover, it may also help to review and plan possible solutions based on sustainable tourism development. In the early stages, measures based in sustainable tourism should be implemented, responsible tourism initiatives should be strongly supported, and a good dialogue and level of participation among the different investors and actors should be maintained. It is crucial to enforce sustainable solutions and to face the dangerous outcomes of using the city to serve tourism instead of being merely consumed by the profit mass tourism represents.

4. Mapping the less known Barcelona – An inspirational example of a mapping exercise that aims to invite tourists to discover and explore less busy areas of the city. From monuments, gardens, architecture, museums, viewpoints, historical buildings, leisure and recreational areas to food places, the map could suggest alternatives to the mainstream tourist areas and typical routes. Source: Authors.

Notes

1.Referring to those who, while travelling, are aiming to have authentic local experiences and engage more with the inhabitants, and are more respectful towards the surroundings. These travellers can be defined by their curiosity to discover new places, to get a real sense of the place, people and the city’s beauty, instead of simply consuming it (Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014).

REFERENCES

References

— Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2017a. Strategic Plan. Tourism [online] Available at:

— Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2017b. Responsible and Sustainable Tourism [online] Available at:

— Angulo, S., & Muñoz, O., 2009. La prolongación del paseo Marítim, otro paso en la apertura de Barcelona al mar. [online] La Vanguardia, 25 June. Available at:

— Barcelona Metropolitan, 2015. Limit on tourist access to la Boqueria. [online] Available at:

— Bye Bye Barcelona, 2014. [documentary film] Barcelona: Eduardo Chibás. [online] Available at:

— Chitrakar, R.M., 2016. Meaning of public space and sense of community: The case of new neighbourhoods in the Kathmandu Valley. International Journal of Architectural Research, 10(1), pp.213-227.

— COAC, 2017. El Ayuntamiento de Barcelona adjudica al equipo km-ZERO el concurso para la mejora de la Rambla, Barcelona. [online] Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya. Available at:

— Decidim.barcelona, 2018. Decidamos la Barcelona que queremos. [online] Available at:

— ETE, 2018. Definition of sustainable tourism. [online] Available at:

— Fainstein, S. & Gladstone, D., 1999. Evaluating urban tourism, In: D. Judd & S. Fainstein, ed. 1999. The Touristic City. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. pp.21-34.

— Goodwin, H., 2016. Managing Tourism in Barcelona. [online] Harold Goodwin – Taking Responsibility for Tourism. Available at:

— Hunt, E., 2017. ‘Tourism kills neighbourhoods’: how do we save cities from the city break? [online] The Guardian, 4 August. Available at:

— JAM Hostel Barcelona, 2017. [online] JAM Hostel Barcelona. Available at:

— Jones, P., Petrescu, B., & Till, D., 2005. Introduction. In: P. Jones, D. Petrescu & J. Till eds. 2005. Architecture and Participation. London and New York: Spon Press. pp.xiii-xvii.

— Klingmann, A., 2007. Brandscapes. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

— Kettle, M., 2017. Mass tourism is at a tipping point – but we’re all part of the problem. [online] The Guardian, 11 August. Available at:

— NPR, 2017. For Barcelona, Tourism Boom Comes At High Cost. [online] Available at:

— Sampaio, G., 2018. O processo de gentrificação em curso nas cidades (e periferias) de Lisboa e Porto. [online] O Jornal Económico, 2 February. Avalable at:

— Sezgin, E. & Yolal, M., 2012. Golden age of mass tourism: Its history and development. In: Dr. M. Kasimoglu, ed., Visions for Global Tourism Industry – Creating and Sustaining Competitive Strategies, 1st Ed. London: InTech.

— Theng, S., Qiong, X.; Tatar, C., 2015. Mass Tourism vs Alternative Tourism? Challenges and New Postitionings. [online] Études caribéennes, 31-32 | August-December 2015. Avalable at: https://journals.openedition.org/etudescaribeennes/7521 [Accessed 19 May 2018].

— UNWTO, 2017a. 2016 Annual Report, Madrid: World Tourism Organization. Available at:

— UNWTO, 2017b. Tourism Highlights, 2017 Edition, Madrid: World Tourism Organization. Available at:

— Wainwright, O., 2016. Gentrification is a global problem. It’s time we found a better solution. [online] The Guardian, 29 September. Available at:

— Zeng, B., 2013. Social Media in Tourism. Journal of Tourism & Hospitality, 2(125). DOI: 10.4172/2167-0269.1000e125.

Elisa Diogo Silva is a young architect (MA) and a recent graduate in urban design (MSc) from Aalborg University in Denmark. She has a flair for mobilities design, creating spaces with and for people, sustainable urban developments, and for instigating future urban scenarios. Furthermore, she is passionate about strategic urban development, democratic design, and the relationship between people, physical settings and less-material occurrences taking place in the urban milieu.

Cristina Roxana Lazăr is a freshly graduate of urban design (MSc) from Aalborg University in Denmark and urban planner (BA) from Bucharest University. Her work emphasizes how positive impacts can be planned and generated through the use of tactical urbanism, people-oriented strategies, urban catalysis, placemaking and relation user-space theories. Moreover, she is passionate about art and collage rendering and in her work tries to bring a creative perspective to urban spaces and contemporary ways to design them.

Volume 2, no. 1 Spring 2019