From the emergence of urban lighting to a new culture of consumption: department stores and the public life of women

– Nina Margies

Fear and fascination meet us as we approach the nocturnal city and accompany us along our way. We enter a world that is both familiar and strange, a landscape full of light and rich with shadows, the receptacle of our desires and of our hidden, unspeakable fears (Schlör 1998: 9).

I. Introduction

The first public lighting system that was centrally organised and legally standardised emerged in France at the end of the 17th century. It was organised based on the biological rhythm of nature (Schivelbusch 1995: 90). Adapted to the seasons and the moon, street lighting was reduced or completely turned off in summer and by full moon.

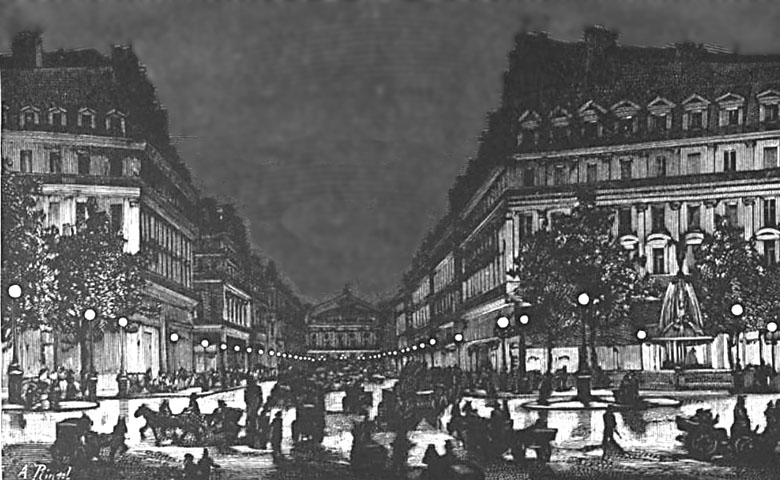

The ambition to make street lighting more effective inspired constant technical and spatial improvements. Thus the distance between street lights was increasingly reduced and new types of lanterns were developed. In the 1760s the oil lamp, réverbère, was introduced in France which was then replaced by gaslight in the mid 19th century. The 1880s marked the beginning of the electrification of the modern city. Soon the use of incandescent lamps became common and so the direct connection between fire and light disappeared for the first time (Nye 1992: 2).

Public lighting became a symbol of progress and modernity. It stood for festively illuminated cities, overwhelming joy and beauty as well as the lengthening of the night connected to pleasure and amusement. At the same time, however, one feared the loss of imagination, and “the enslavement […] of night life […] above all through advertising” (Schlör 1998: 69).

The development of new lighting systems – as these impressions illustrate – was closely linked to commercialisation and the emerging (mass) culture of consumption. This aspect is already reflected in the decisions about where in the city street lighting should be introduced first. In Berlin, for example, the boulevard Unter den Linden was the first street illuminated with gas lights (1826). In addition to its power-symbolic significance, the boulevard was also an important address for going out and shopping. Hence, at the beginning, primarily the (main) shopping streets were lit as well as squares that were considered worthy of illumination (Schlör 1998: 59). The evolution of new lighting systems thus served not only exclusively power-political and security reasons but also followed the principle of attracting “more people onto city streets at night [and] generating more income from retail sales and recreational spending” (Dennis 2008: 132).

The following essay addresses this development from a perspective of urban history. Its first part shows how urban lighting (especially commercial lighting) was related to the emergence of a new culture of consumption with department stores being one of the central institutions of early consumer capitalism. It describes how they made extensive use of commercial lighting to represent and advertise products aiming to turn the shopping experience from a necessity into a fantasy.

The development of urban lighting and the emergence of department stores also changed the way the city was perceived, imagined and inhabited. New professions, identities and practices emerged, especially for women. The second part of the article therefore highlights how new possibilities opened up for them to participate in and shape urban life. It illustrates how women, in particular of the middle-class, gained access to new identities within the context of the emerging commercial spaces, both through new productive and leisure activities.

1. Former shopping and entertainment arcade in Berlin. Author: unknown. Source: Collection of the Technical University of Berlin Scanned from Janos Frecot & Helmut Geisert: Berlin in frühen Photographien 1857–1913. Schirmer/Mosel, Munich 1984. ISBN 3-88814-984-3.

II. Urban lighting and a new culture of consumption

Department stores: profiteers of public lighting

The development of public lighting generated a shift in the daily routine: the retail sector and department stores were able to extend their opening hours often until midnight offering their clientele the new experience of night-time shopping.

- A sea of light stretches out before us. To the right and left, one show window after another displays luxuries for ladies and gentlemen alike. An elegant stream of people, full of cheer and with all the time in the world, laughs and flirts its way down the street. Strollers, flâneurs. Ahead on Wittenbergplatz, magical lights, rare delicacies, silk, gold brocade, bronzes, ostrich feathers, show windows that are more like jewellery cases: the new department store (Leo Colze in Fritzsche 1996: 148).

Originating in the 19th century, department stores were “made possible by mass concentrations of capital and people and by the expansion of the transportation system” (Leach 1984: 322). In the illuminated city centres, they soon belonged to the main attractions and quickly became the epitome of the new culture of consumption. Their success is also closely linked to two dynamics: On the one hand, there was the strategic measure to expand the premises that had previously been used for the simple sale of textiles and groceries and to diversify their array of products. On the other hand, there was the more conceptual consideration to turn department stores into an unforgettable experience that took inspiration from the world of theatres and international exhibitions (Dennis 2008: 296-309). While street lighting ensured that the inner cities with their commercial spaces were visited even after nightfall, the emergence of commercial lighting made it possible for department stores to present themselves as places of spectacle and fantasy. Accordingly, they were among the first to use this form of commercialised illumination whose use of a wide variety of colours enabled a completely new form of advertising commodities.

2. Curt Teich postcards of Marshall Field & Co’s Retail Store, Chicago. Left: Tiffany Mosaic Dome. Right: An Interior Decoration.

-

Some stores had fountains illuminated by colored light and had electrical towers that projected “varying hues.” In 1902 Marshall Field in Chicago erected its magnificent opalescent glass dome, designed by the Louis C. Tiffany Studios and illuminated by four “golden globes of light” suspended beneath, the largest single piece of iridescent glass mosaic in the world. By the early 1920s decorators adopted spotlighting and colored screens to transform interiors into beautiful spaces (Leach 1984: 324).

Department stores such as Au Grands Magasins du Printemps in Paris, Harrods in London and Kaufhaus des Westens in Berlin lured with the promise to turn strolling and shopping into an adventure and succeeded in creating new needs and desires. They were stylized into places of festive atmosphere and enjoyment, while “decisively setting off the world of consumption from that of production” (Leach 1984: 323). Their shop windows played an important role in this as they served as a presentation surface mirroring what was worth having and striving for.

The illuminated stage for consumption: display windows

- The illuminated window as stage, the street as theatre and the passers-by as audience – this is the scene of big-city night life (Schivelbusch 1995: 148).

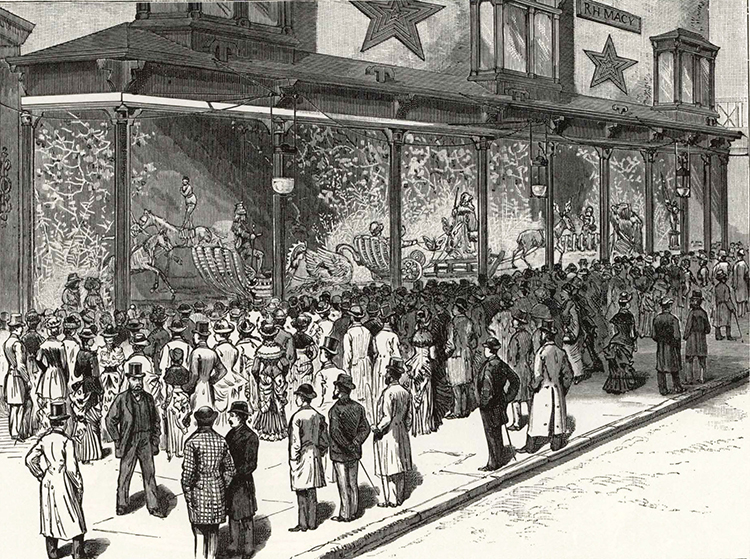

The evolution of urban lighting also had visible repercussions on the lighting techniques used to illuminate shop windows. While at the beginning the light source was still placed inside the shop window, with the appearance of gaslight it was installed outside. When electric light emerged it enabled department stores an effective form of stage lighting which literally transformed the display window into the store´s stage. (Schivelbusch 1995: 148).

As window displays and their decoration increasingly gained in importance, department stores sought to obtain premises providing a high number of (plate-glass) windows (Dennis 2008: 302). In order to decorate them imaginatively, glass and mirrors were increasingly used in addition to light.

-

Glass mediated between people and goods in a new way; it permitted everything to be seen and at the same time rendered it inaccessible. Mirrors of all kinds appeared to create the “illusion” of space and abundance, to “conceal” defects in store architecture and to make each article “show to advantage” (Leach 1984: 323).

This shift from an ordinary window to the store´s representation platform “began to transform the city´s visual organization and texture” (Nye 1992: 49) and changed in particular the appearance of main shopping streets. Like a mouthpiece they communicated to passersby what could be discovered inside the department store. Their task was not only to inform about the variety of products, but also to enchant potential customers. Colourfully illuminated and decorated shop windows created an atmosphere of magic, desire and enchantment that invited one to escape from everyday day life. To do so commodities were presented around varying and often explicitly exotic themes.

- Stores were decorated to look like French salons, rose and apple-blossom festivals, “the streets of Paris,” Egyptian temples, semitropical refuges in the middle of winter, Japanese gardens, the “October woods.” (Leach 1984: 322).

In Berlin, a show window contest was held from the beginning of the 20th century, transforming the city “into a magical landscape of wares” (Fritzsche 1996: 155). When department stores increasingly offered events such as theatre performances, concerts or fashion shows in addition to goods, shop windows extensively advertised these new attractions, too.

3. R.H. Macy’s mechanised Christmas windows at Sixth Avenue and 14th Street in 1884: ‘A Holiday Spectacle.’ Source: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (December 20. 1884), 284.

Large glass windows, eye-catching decorations and colourful lights ensured that department stores opened up to the street. Their self-image changed, too, as they increasingly promoted themselves as a “people’s store” (John Wanamaker in Leach 1984: 331). They offered numerous, often, free services (e.g. gifts, libraries, cultural events, etc.) and for the first time department stores did not oblige their customers to purchase something when entering the store. As a result, the clientele – predominantly female – gradually changed. The previously private circle of upper-class and aristocracy widened to a broader and more anonymous client base including the bourgeoisie and middle-class strata (Dennis 2008: 306). This development of department stores opening up and luring ever more customers had not only an impact in terms of class but also in terms of gender.

III. Women and the new culture of consumption

The emergence of urban lighting and later of department stores as new commercial spaces in the city also affected the public life of women, both in terms of their professional and leisure opportunities. As working or consuming women, they increasingly shaped the cityscape claiming, little by little, the public realm (the streets) as well as commercial sites (department stores).

On the one hand, they took on the role of female employees working as sales assistants, seamstresses or store “hostesses” that guided customers. These activities were mostly performed by women with lower-class backgrounds. But middle-class women, too, occupied positions within the department store hierarchy, as the historian Leach describes it for New York and other large US cities:

- Middle-class women found jobs as store doctors, as assistant merchandising managers, as professional shoppers, and as traveling models. In many stores they predominated as advertising managers and as educational social-welfare directors. A number of women [even] traveled the world as sales representatives […] [or worked as] female buyers […] [who] commanded their own budgets, acted as individual merchants in their own departments, received excellent salaries, and went everywhere in the country and abroad to discover markets and styles (Leach 1984: 332).

4. Christmas shoppers, window shopping, New York ca. 1900. Source: Bain News Service, publisher.

On the other hand, women, particularly of the middle class, took on the role of consumers. Equipped with financial resources and leisure time, they increasingly populated the public realm and the new commercial sites. They strolled in the illuminated public spaces, along the extensively decorated display windows and met for shopping trips in department stores. Street lighting and department stores that were explicitly catering to female needs and desires contributed to making this new freedom possible.

By the end of the 19th century, several department stores were already offering “free child-care facilities – small nurseries and, later, elaborate playgrounds staffed by trained personnel” (Leach 1984: 329) which made it possible for women to come with their children or to wander through the shops on their own without needing to worry.

Using diary entries and novel excerpts, Leach (1984) describes how (in the US) this new culture of consumption and the liberation of women were connected. Department stores were not only one of the most important and advanced employers, but also a place where women could dream of immersing themselves in other worlds and adopting new identities. They became the symbol of the modern and independent woman who suggested (and for some made possible) the stripping off of traditional role allocation as the products and worlds displayed in the shop windows promised a self-determined and more exciting life (Leach 1984: 339-342).

Sometimes, these consumption-oriented messages also mingled with political ones. At the beginning of the 20th century, for example, department stores also served as a stage for women’s rights movements in the US. This led to collaborations between suffragist publications and some large department stores, in which they offered each other advertising space.

- With the willing consent of department stores, [suffragists] decorated store windows in the “colors of the Suffrage Party.” Stores everywhere volunteered their windows and their interiors for suffrage advertising. In June 1916 Chicago’s Carson, Pixie Scott installed a wax figure of a suffragist in one of its windows, a herald of the coming convention of the Woman’s Party in that city (Leach 1984: 339).

New forms of female pleasure-seeking

Increasing possibilities of moving in and through the (illuminated) public realm and new forms of consumption brought about new forms of female pleasure.

The historian Joseph Prestel describes how in Berlin, the (illuminated) space in and around the department stores (of Friedrichsstraße) became a place of encounter and amusement. Strolling along the streets or lingering in front of strikingly decorated display windows became the ideal opportunity for romantic encounters (Prestel 2017: 86-87). As if casually, glances could be exchanged, one mingled among passersby and employees of department stores and thus got into conversation.

The new commercial sites also enabled and promoted public drinking practices of women. Whereas they had previously practiced this activity predominantly in private space, it now also shifted to the public realm. In Chicago, as the historian Emily Remus shows, the figure of the tippling lady emerged. These women, usually better off, sought refreshment from strolling and shopping. Since at the beginning there were hardly any places where respectable unaccompanied women could dine, let alone drink alcohol, they started to frequent the nearby drug stores (Remus 2014: 756).

-

The chief allure of these establishments was the soda fountain, where clerks dispensed carbonated water mixed with homemade tonics and patent medicines such as Coca-Cola and Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound. These nostrums contained between 7 and 50 percent alcohol by volume and were said to appeal to shoppers seeking an afternoon pick-me- up (Remus 2014: 757).

When other establishments became aware of the female purchase power they gradually adapted to the new clientele. “‘Ladies’ menus’ and stimulating drinks” (Remus 2014: 757) were offered and soon there was no department store left which did not have its own restaurant (Remus 2014: 758). The shop windows, too, were adapted accordingly. When the sale and consumption of alcohol became possible in department stores, the shop windows praised this new range of products from wine to liquors.

Women with money and time to spend, thus, increasingly occupied the commercial drinking spaces and claimed their right to individual pleasure and excitement. In the often gender-separated rooms within the department stores and thus mostly undisturbed by the male gaze, public drinking became a practice of leisure and sociability for women beyond the private sphere of their homes.

“A landscape full of light and rich with shadows” – emancipating effects and (new) inequalities

The increasing access women gained to the (illuminated) public realm and the city´s new commercial spaces had some considerable emancipating effects. As working or consuming women it enabled (some of) them to imagine or even create new identities within the culture of consumption and to claim their part in the generally male dominated public space. At the same time, their increased participation in public life did not remain without conflict and the formation or perpetuation of inequalities.

The new female subjectivities and most of their related (pleasure-seeking) practices rooted in the culture of consumption. However, many of the commercial spaces like department stores with their advertised pleasures such as shopping, dining or drinking and the associated image of the new independent, fashion-conscious and sexually liberated woman, were generally only accessible to (white) middle and upper-middle class women with sufficient financial resources and leisure time. For those who had neither the money, the time nor sufficient respectability often remained only “the misery many poor women must have felt as they passed the windows of city retail stores, which revealed to them an unobtainable world of luxury” (Leach 1984: 320).

But middle-class women with money to spend also felt the other side of the coin. The sociologists Talja Blokland and Alan Harding, for example, point out that “the development of department stores in the nineteenth century gave them [indeed] a legitimate place in the city as consumers, but the lore of the products that would enhance their homes also stressed their role as homemakers and stressed the emotional, not instrumental nature of their shopping behaviour” (Blokland & Harding 2014: 203). In fact, despite their increasing presence and purchasing power, women were regarded as easily manipulable and impulse-driven beings who, attracted by colourfully illuminated and opulently decorated shop windows, could hardly resist the temptations of consumption.

5. Department Store Wertheim in Berlin in 1900. Author: Unknow. Source: https://www.bildindex.de/

The presence of women on the streets, especially after dark, also proved to be a moral problem.

Publicly drinking women in Chicago were accused of fostering moral decay and destabilising ideals of family, motherhood and domesticity. Religious and civic associations (e.g. temperance movements), which included numerous male activists, called for a return to traditional values and appropriate female behaviour that implied renouncing personal pleasure-seeking activities (Remus 2014: 770-773).

The situation was similar for women in the late 19th century in Berlin, who, after dark, strolled alone along the (shopping) streets, whether for pleasure or on their way home from their shift in department stores. Under the guise of moral order they often became objects of suspicion, policing and sometimes even arrest if they were suspected of being a prostitute (Prestel 2017: 88-91).

The main focus was therefore on regulating female behaviour and preserving norms of female respectability. Concerns about the moral climate “reflected [therefore especially male] anxieties about women who dared to indulge their desires in public” (Remus 2014: 775) and by doing so challenged “the notion that men alone could pursue sensuous pleasure in public” (Remus 2014: 753).

References

— Blokland, T. & A. Harding (2014) Urban Theory. A critical introduction to power, cities and urbanism in the 21st century. Los Angeles/London: Sage.

— Dennis, R. (2008) Cities in modernity: representations and productions of metropolitan space, 1840-1930. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— Fritzsche, P. (1996) Reading Berlin 1900. London: Harvard University Press.

— Leach, W. R. (1984) Transformations in a Culture of Consumption: Women and Department Stores – 1890-1925. The Journal of American History, 17, 2, pp. 319-342.

— Nye, D. (1992) Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880- 1940. Cambridge, Mass: MIT.

— Prestel, J. B. (2017) Emotional Cities. Debates on Urban Change in Berlin and Cairo, 1860–1910. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

— Remus, E. A. (2014) Tippling Ladies and the Making of Consumer Culture: Gender and Public Space in Fin-de-Siècle Chicago. The Journal of American History, pp. 751-777.

— Schivelbusch, W. (1988) Disenchanted night: the industrialisation of light in the nineteenth century. Oxford: Berg.

— Schlör, J. (1998) Nights in the Big City. London: Reaktion Books.

Nina Margies is an urban sociologist. She is currently pursuing her PhD at Humboldt University of Berlin and is a Research Fellow at the École des Hautes Études Hispaniques et Ibériques (EHEHI). Her research interests include emotion & space, emotion management and the global transformation of work. She is co-founder and member of the “Urban Research Group: Global Urban Youth” at the Georg Simmel Center for Metropolitan Studies.

Volume 2, No. 2 October 2019