Lighting master plan: The night time face of Timisoara city

– Adela Petra Popa

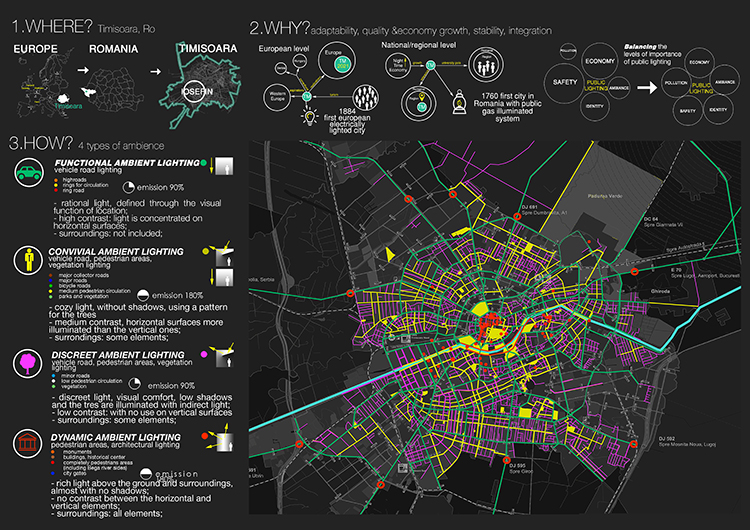

1. The macro strategy can be applied on a medium sized european city (100,000-500,000 inhabitants), in this case the city of Timisoara, with a population of 319,279 habitants (2011). Source: Author’s own.

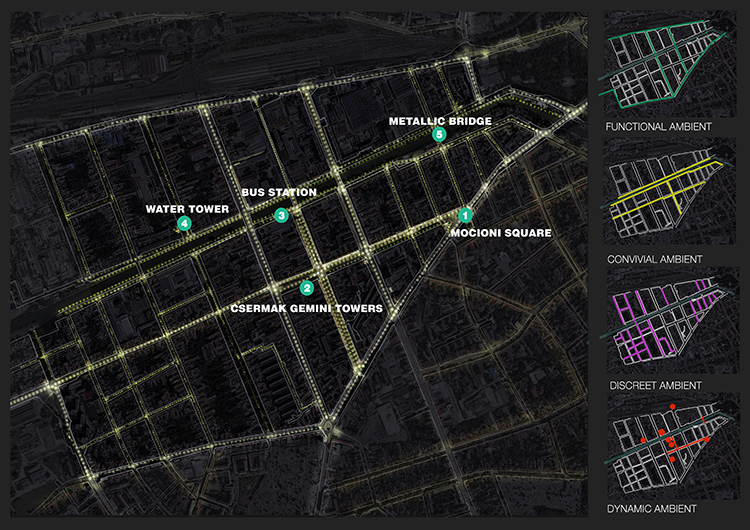

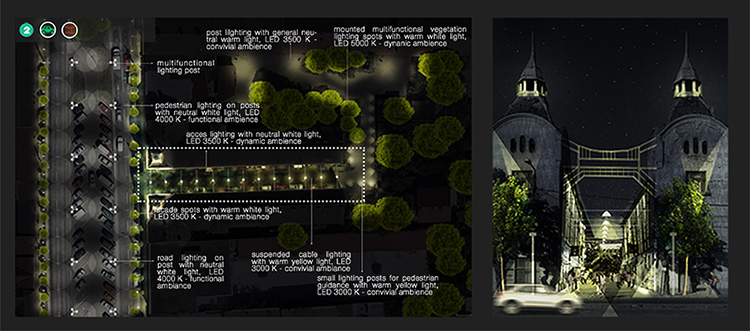

2. Micro strategy: Being one of the three main historical neighbourhoods in Timisoara, is one of the reasons for taking Iosefin neighbourhood as a case study. There are three main objectives for defining the strategy in the researched zone: increasing the quality of life, increasing the quality of spaces and the growth of the night time economy. Source: Author’s own.

3. In order to generate the lighting master plan, first we have to create curiosity in people and awareness for the importance of light in public spaces, therefore 5 diverse points of interest in the entire district were chosen. Source: Author’s own.

4. The existing lighting system is based on incandescent lamp posts, configured identically in all types of spaces, a fact that shows a failure to recognise the individual identity of spaces and a lack of sensitivity towards the people living in these places. Source: Author’s own.

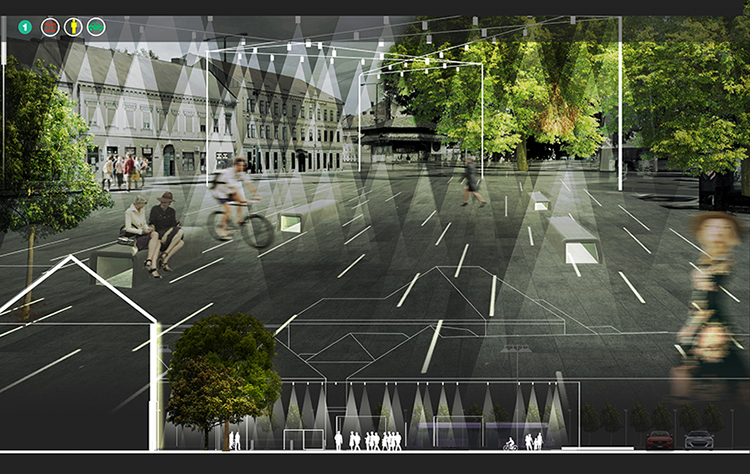

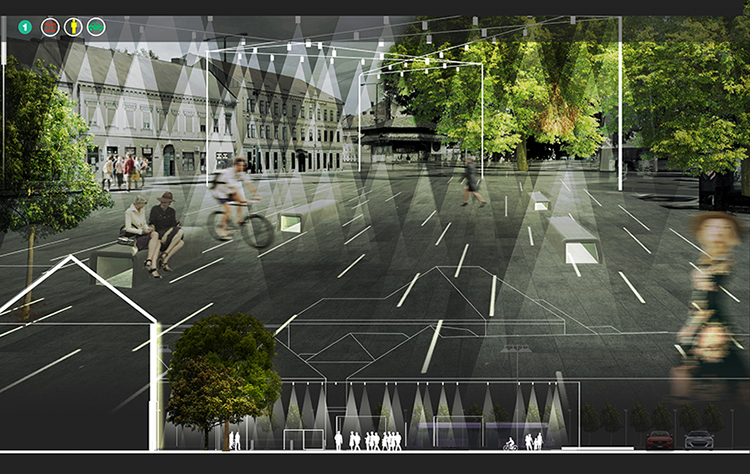

5. Mocioni Square: This is a multifunctional space, which aims to have the highest level of activity in the entire district, being the main node of circulation in the area and also the end of the perspective from the Metallic Bridge. The lighting is based on the free street concept, with general upper light that can change intensities and a constant lower and softer accent light for the pavement and public furniture. Source: Author’s own.

6. Mocioni Square: Because of the diverse uses that we may find around the square, the lighting concept is strongly connected with the night time schedule and also with the cultural schedule, with the agenda of providing a safer, brighter (if needed) and warmer atmosphere in the space. Light connects the square with the surroundings by using different typologies of ambience depending on the street hierarchy (high traffic flow – functional ambience, medium traffic flow – convivial ambience) creating a lighthearted mood for the entire place. Source: Author’s own.

7. Csermak Gemini Towers: This is an adaptation process. Presently the space between the towers is drowned in complete darkness during the night and used as an illegal parking lot during the day, profoundly neglecting the commercial potential of the street. Source: Author’s own.

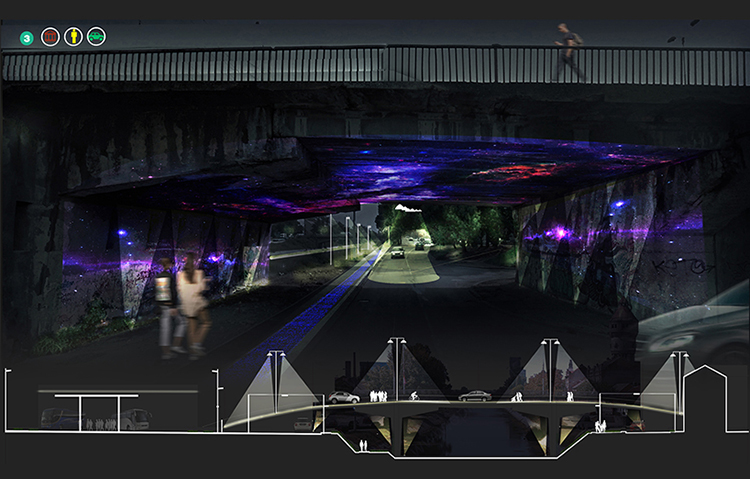

8. Bus station & Bridge lighting [elevation, perspective, section]: Besides its historical importance, Iosefin district is well known as the main circulation node of Timisoara; we are either talking about train transport or bus transport or even ship transport (back in the old times). A common problem in Timisoara is the lack of lighting under the bridges, a fact that makes people feel insecure, creates unsafe spots for the community and good shelter for the homeless. Trying to discourage under the bridge living, the proposal creates an astral ambience through simple fluorescent paint and directional spotlights, which aims to reveal art in unexpected places. Source: Author’s own.

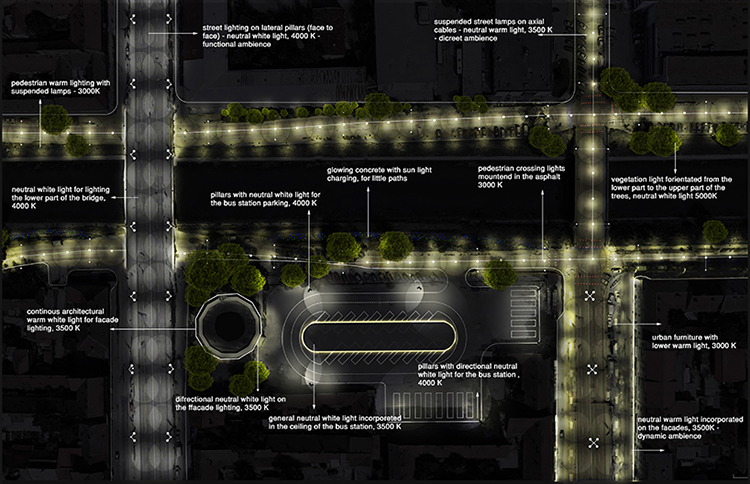

9. Bus station & Bridge lighting [plan]: Besides its historical importance, Iosefin district is well known as the main circulation node of Timisoara; we are either talking about train transport or bus transport or even ship transport (back in the old times). A common problem in Timisoara is the lack of lighting under the bridges, a fact that makes people feel insecure, creates unsafe spots for the community and good shelter for the homeless. Trying to discourage under the bridge living, the proposal creates an astral ambience through simple fluorescent paint and directional spotlights, which aims to reveal art in unexpected places. Source: Author’s own.

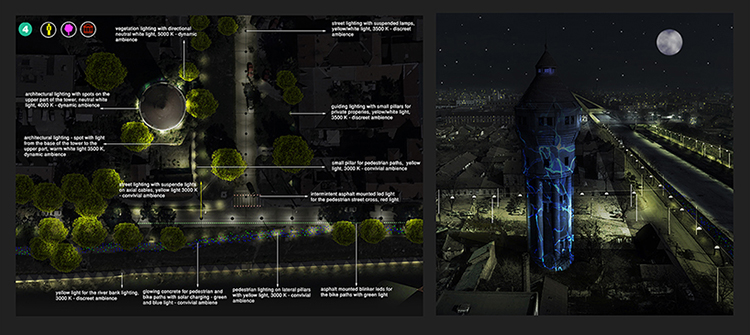

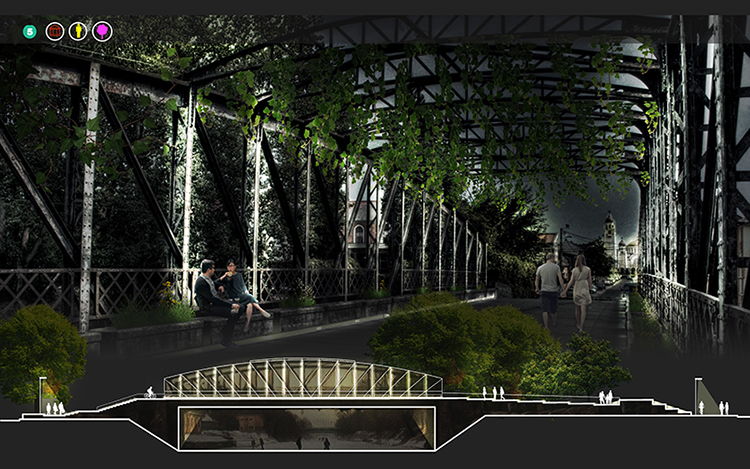

10. Water Tower: Besides the colossal aspect of its presence (52 meters tall), the disaffected water tower can become an iconic point for Timisoara through architecture and structure, being a site of exploration for competitions and investors. The lighting proposal focuses on two approaches: 1. Architectural lighting with directional spotlights, which can be applied throughout the entire year; 2. Video mapping with water or nature themes, which can be applied occasionally to remind us of the old use, creating an idyllic atmosphere. Source: Author’s own.

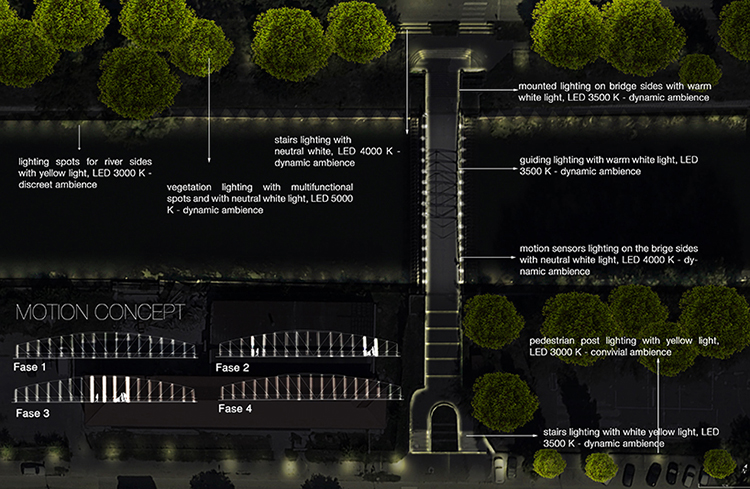

11. The Metallic Bridge [perspective, section]: The bridge is shrouded in legends; people say that the man who built the Eiffel Tower also built this bridge. But its unicity for sure is the fact that it is the only pedestrian bridge in Timisoara with an industrial metal structure that connects the two sides of Iosefin district. Shown as a playground, as a romantic path or as a simple connection, the bridge facades changes in rhythm with the intensity of the pedestrians, through a smart motion system that changes with movement, creating playful light if needed or discreet light in general. Source: Author’s own.

12. The Metallic Bridge [plan, motion concept]: The bridge is shrouded in legends; people say that the man who built the Eiffel Tower also built this bridge. But it’s unicity for sure is the fact that it is the only pedestrian bridge in Timisoara with an industrial metal structure witch connects the two sides of Iosefin district. Shown as a playground, as a romantic path or as a simple connection, the bridge facades changes in rhythm with the intensity of the pedestrians, through a smart motion system that changes with movement, creating playful light if needed or discreet light in general. Source: Author’s own.

I think it is time to understand cities are evolving, and we must realize that they are also taking shape when darkness falls. Although today’s cities tend to be active 24/7, planners continue to apply their work only in daylight, therefore neglecting the potential of the nocturnal environment.

Urban lighting not only represents a perceptible physical factor in defining public space, but a discernible factor on a cognitive level, creating moods and feelings, reflections and memories. Having in mind that Timisoara was the first electrically lit city in Europe in 18841, the culture of light is strongly rooted in people’s minds. Creating an adequate nocturnal environment means the reactivation of a lost collective memory, placing an importance on light in our lives, that may connect people despite their age, nationality or social status.

The contemporary city is marked by the profound transformation of the urban environment, where the human factor is a complex actor using multiple services and functions that influence each other in an evolving and interacting system. Appropriate lighting in this environment can improve the sense of security to those who are working during the night, encourage the use of public transportation or just enhance nocturnal walks. Therefore, illuminated public spaces also encourage the process of the „night time economy”2, which is a concept discussed in numerous cities which “don’t sleep” due to the globally growing business sector active between 6 pm and 6 am. This approach facilitates the development of activities during the night like in a normal working day.

On a general scale, this concept encompasses all types of environments in such a way as to allow economic development even after the usual working hours and it’s based on the fact that cities are increasingly active overnight. Although this need is a priority in many cities, here we talk about the presented case study of the Iosefin district—one of the three oldest neighbourhoods in the history of Timisoara, Romania—where the strategy could be selectively applied, responding to the needs of the district. Trying to extend the day can be done only in the places where the uses demand it, such as areas with business offices, hotels and bar spaces, and a small number of medical and food shops, and only for as much time as the as the activity of these spaces requires it.

These observations, on the need for certain uses and levels of activity, led me to choose the Iosefin district [Image 2]. The district embodies the high levels of complexity of the historical, functional, spatial, architectural and social development of this area, ideal conditions for converting it into a smart social neighbourhood. In order to achieve a holistic approach to the city, after analyzing the city’s needs four types of ambient lighting were determined [Image 1], generally applicable and with an integrative role for the component parts of Timisoara, including the studied area: functional ambience for major car streets with white light, convivial ambience dedicated to pedestrians with warm light, discreet ambience meant to protect the nature with dimmed warm light and dynamic ambience which enhances the art and architecture with orientated and strategic light. Having in mind that it is scientifically proven that lighting towards the red end of the spectrum is known as warm light and is associated with emotionally positive feelings and cool lighting in the blue direction of the spectrum is associated with reduced intensity of emotion, each of these ambient lights has the purpose of converting the simple light into emotional light by creating a certain mood or influencing the mood, depending on the spot you are in3. With the help of today’s LED technologies, by replacing the old sodium and incandescent lamps all over the city, not only can we reduce the energy waste, but we can also control the light and play with our emotions through brightness and saturation, amplifying our feelings with powerful lights or dimming them with dramatic black and white contrasts.

The city’s chameleon side starts to appear when darkness is falling, and each of these environmental lighting schemes are found in a strong connection with the diverse scenarios that the night is offering us, depending on the time during the night and depending on how the space is used in that moment. With a high percentage of residential areas in the district, street lights are dimmed to a lower level between midnight and sunrise to decrease the energy waste and the light pollution4, with the exception of the main boulevards and on days of celebrations, festivals or parades. Having this strategy as a baseline, we can make the space multifunctional without disturbing the uses, the physical spaces or the communities who are populating the neighborhood. The idea is not only to create a suitable environment for the buildings and for the spaces, but to also create livable places for the people who, above all, are the main actors in the city. Focusing on the community, the adaptation of light encourages them to explore the neighborhood in an undiscovered way of perception, creating joyful, social and walkable spaces, because people attract people and a place without people becomes only a space, not a life creator, as a neighborhood is supposed to be.

By offering properly lit cities, the first issue addressed will be the increment of safety and security on the streets, followed by the decrease of light pollution. Creating cultural events during the night in unvisited spaces will extend the range of walkability generating a solution for the third issue which aims to prevent social segregation and intercultural conflicts. Ensuring and strengthening the active use of the public realm by generating more pedestrian friendly and flexible public spaces, making buildings more attractive by night, it’s the answer to the unawareness of the residents about the unique places they are living in and about the importance of light and dark, as a life generator which keeps the city active like a perpetual motion machine.

Notes

1. A crucial moment for the future of Timisoara in terms of urban planning and mobility: http://www.timisoara-info.ro/en/sightseeing/historical-quarters/cetate/tours/224-felinarul.html; and also more information about Timisoara Capital of Culture in 2021: https://timisoara2021.ro/ro/

2. See more about cities that don’t sleep: https://www.arup.com/perspectives/cities-alive-lighting-the-urban-night-time

3. More information about how light changes your perception can be found on: http://changingminds.org/explanations/emotions/emotions_light.htm

4. See more about energy waste and light pollution on the International Dark Sky Association: https://www.darksky.org/light-pollution/

+

The work presented here is part of the Lighting Master Plan for Timisoara European Capital of Culture 2021 thesis at the School of Architecture, from Polytechnic University of Timisoara, Romania presented in 2017 and also a part of the ongoing masters thesis from the same university.

Adela Petra Popa (1992) is an architect and an urban planner, who graduated the Polytechnic University of Timisoara in 2017 and is currently studying for her masters thesis at the same University. Her thesis topic is emotional lighting design in urban spaces. After studying and working in recent years with architects and artists in Spain, Portugal and Italy, Petra Popa returned to her home town, Timisoara in 2020 to work in an architecture office and complete her studies. In her field trips across the Europe, she realized the importance of light in people’s lives and the relevance of an existing emergency lighting system in case of natural calamities.

Volume 3, No. 2 June 2020