Stråk: Visualising an urban design concept – Reflections on verbal and visual approaches in research

– Karin Grundstrom

In the Swedish metropolitan regions, the word stråk has been incorporated into urban design and planning practice as an approach to (re)-connect the current polarised cities. Several design proposals of how to build a stråk has been presented in drawings and planning visions, in cities such as Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö, yet the conceptualisation of the term has been lacking. In order to further the understanding of stråk, the research project ‘Transforming Dual Cities’ was set up to investigate the practices and discourses embedded in the development of the Rosengård Stråk in Malmö, Sweden. Elsewhere, I have presented findings from this research and I have argued that in urban design, stråk can be conceptualised as an inter-scalar urban corridor (Grundström, 2014; 2019). In the research process semi-structured interviews were carried out in parallel with visual note taking in the form of mapping and models. This article sets out to reflect on the potential of such visualisations in research.

The creation of physical and digital models is a traditional approach in architecture and urban design to visualise what is yet not constructed. Such models are primarily used in parallel with drawings and sketches to visualise ways forward in the design process. The meaning of models from this approach entails investigating light conditions and studying construction details, dimensions and relations between different parts of a building. It also entails using models as communication devices between users and actors involved in the construction phase (Bjerre Hjortenberg et al., 2012). Such physical and digital models are foremost used as concrete examples of future buildings and housing areas or as visualisations of complex design details. However, in parallel to this approach, an analytical approach is emerging. According to Mitrović (2011:191) the rise of the material turn and ‘the demise of the linguistic turn means that argumentational premises about visuality, once precluded by the assumption that all thinking is verbal, are back on the table again’. Thus, understanding drawings, or in this case models, as ‘visual notes’ and as ‘abstractions’ has, during the last decade, been incorporated in design thinking and research (Crowe & Laseau, 2012; Cross, 2011). One example is understanding models as ‘thematised constructions’ (Berkel & Bos, 2007:19); a second example is understanding models as ‘architectural idioms’ (Weiwei studio & Herzog & De Meuron, 2011:176) and a third example is understanding models as representations of ‘values’ later to be expressed in the built work (Schmidt, Hammer Lassen architects, 2012:48). If models previously primarily have served to present future construction for professional practice, and, if recent epistemological notions in contrast suggest that models can also be understood as abstractions and as thinking – which would be of particular importance to conceptualisation in a visual field such as architectural research – then more should be known about how to include visuality in the research process. This is important since it opens up a field of research that includes visuality rather than seeing the visual as merely illustrations of text. Furthermore, it opens up opportunities to include both verbal and visual approaches in research. Based on the research project of the Rosengård Stråk, the aim of this article is to reflect on the relation between verbal and visual approaches and how they can be combined in the research process.

A Methodological Approach Grounded in Abduction

The research is based in abduction, a theory of science that opens up for thinking ‘both’ rather than ‘either or’, and, for shifting between existing theories and grounded theory in order to discover ‘surprising facts’ (Asplund, 2004; Cross, 2011; Hartman, 1998; Johansson, 2000). During the abductive process I have combined social science and design research methods with the aim to include both verbal and visual approaches. The investigation is a mixed-method case study (Bryman, 2008) based on the Rosengårdstråk in Malmö, Sweden. The selection of the case was based on information-oriented selection (Flyvbjerg, 2006). The Rosengård Stråk represented the largest investment in a stråk in Sweden and was built with the political ambition of supporting integration and social sustainability (Malmö stad, 2010).

The research comprises one part based on social science methods and one part on design research. In the part on social science methods seven semi-stuctured interviews (Kvale, 1997) were carried out with key officials in Malmö municipality. Respondents were the mayor of Malmö, the director of the Department for Strategic Planning, the director of the Urban Planning Department, the director of the Traffic and Roads Department, the director of the Environmental Department, the director of the city district council and a chief planner. In their daily work, these key officials influence planning documents and planning policy, and thus the meaning they ascribe to stråk has important implications for how it is defined in discourse and in planning practice. Alongside this, is the part of the research based on design research. In planning and urban design, meaning is not developed solely through words (Mitrović, 2011) but also through visual analysis based in practices of mapping, designing models and drawing (Belardi, 2014; Crowe and Laseau, 2012; Groat & Wang, 2002). Crowe and Laseau state that ‘visual notes’ are ‘simply the graphic equivalent of written notes’, and, that the potential of visual note taking extends beyond simple recording of information to also include analysis. They argue that ‘analysis can be facilitated through the deliberate modification of visual notes’ for example through abstraction. ‘One way to go about abstraction is to select only one or a few features for illustration’ in order to see patterns and relationships more clearly. ‘Another form of abstraction is the conversion of visual notes to less specific forms, a type of visual code or language; this process can reveal generalisations and structures that are transferable to other contexts.’ (Ibid, 2012:28). The main focus for Crow and Laseau is on design practice and design problems, but I would argue that their thinking is also of relevance to research and the development of concepts. Notions of ‘patterns’ as a means of analysis and ‘abstraction’ as a means of generalisation are central notions also in scientific thinking (Hartman, 1998), as well as in what Mitrović (2011) refers to as ‘argumentational premises of visuality’. Following this line of thinking, the research included a visual approach of taking visual notes and broadening the understanding of models to also include analysis and interpretation. The research evolved in two phases, one initial phase with interviews and mapping and a second phase with interviews and development of models.

Mapping Stråk

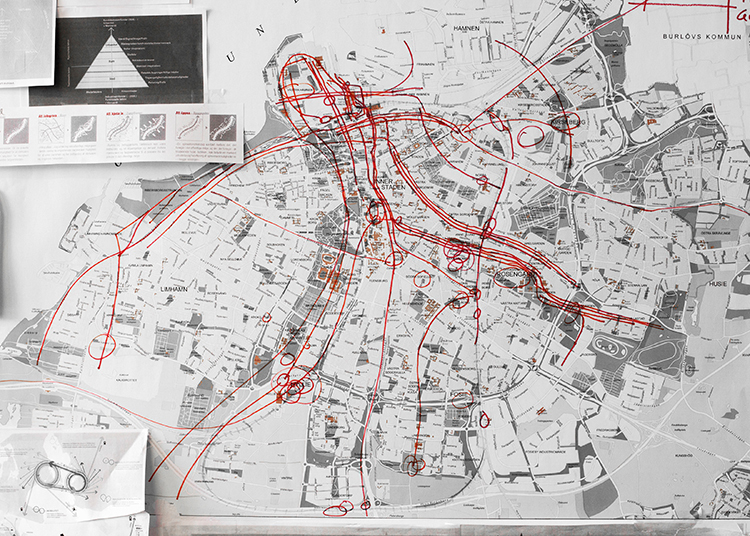

The first phase of the research comprised interviews and mapping. The key officials interviewed were asked to define the meaning they ascribe to stråk in urban design. The assumption was that the meaning specifically used in urban design would differ from how stråk is used in every day language. In Old Norse, stråk is defined as ‘a pathway on which people often walk or linger. People were strolling along the new stråk lined with cafés and bakeries’ (Norstedts, 1988). Previous research shows that as an embodied practice of walking, a stråk is a pathway that gives the experience of a flow or stream of people moving, a flow that one might either follow or deviate from (Persson, 2004; Wikström & Olsson, 2012). With these definitions in mind, the officials were asked to present their definition of stråk, and in addition, map out the most important stråk in Malmö. Although each planner only saw his or her own drawing, the stråk they drew exhibit a correspondence when compiled into one map [Image 1].

1. Map of the Malmö stråk considered most important by officials interviewed. Collage by Karin Grundström. Photograph by Sarah Newman. Map oriented north. Source: Author.

The stråk drawn by the planners form three main connections. The first is the historical connection. The Medieval Ur-stråk along the coast, which is the trade route that connected Malmö to other cities and to the harbour. The second is the national and international connection, the stråk that connects the three metro stations of Malmö to the Öresund Bridge, to Copenhagen and to the Swedish railway. The third is the socio-economic connection, the stråk that connects the eastern, socio-economically vulnerable districts to the wealthier western districts. In addition, the mapping of stråk revealed that stråk comprises a variation of material forms and ways of moving. Materially, a stråk can be a metro, a cycle path or a bus route and people thus move along a stråk in varying ways; as bus riders, cyclists or pedestrians. This shows that in urban design the concept is used solely for pedestrian movement and public transport and not for private vehicular traffic. Also, the varying materials and varying forms of movement included in the map shows a key feature, which is that movement – rather than specific typologies, types or transportation modes – is central to the design of stråk. This means that the design problem shifts from that of designing a specific type, such as a cycle path or a metro, to that of designing movement. In this phase, interviewing and mapping were parallel practices in the research process and of equal importance to the analysis. Together, the connections, the varying material forms and the focus on movement were all important in the analysis and the interpretation of the results leading to the definition of stråk as an urban design concept.

Modelling Stråk

The second phase of the research comprised interviews and physical models. The interviews were first analysed according to themes that were prominent in the empirical material. Secondly, the interviews were analysed in relation to existing urban design theories and approaches. As part of the analysis, wooden models were developed following the same logic as the verbal analysis. Drawing from the analysis, two aspects that are combined in the concept stood out as differing from other, existing concepts; stråk as an urban corridor in support of inter-scalar connections.

An Urban Corridor

When a stråk is designed and developed, the space between buildings is considered in the form of an urban corridor, which comprises both the ‘floor’ – a path, street or route – and the adjoining ‘walls’. A specific street or route is chosen for redevelopment into a stråk and in order to support a flow of people, the buildings, or ‘walls’, along the street should comprise activities for people. The director of the urban planning department suggests that a ‘good stråk’ is designed according to ideas of a dense built environment:

- One has to be able to concentrate as much (building) mass as possible in the stråk that you choose to work with, so that they become safe and have frequent activities. I believe that density in itself is a positive driving force and we do densify the city, to provide capacity and service and so on. That’s why the New York model is so interesting because it so incredibly dense. Every entrance has enough capacity for a small shop and hairdresser. We will not come that far, but still…

Density and mixed functions, or as the director puts it, concentration of building mass, is related to the idea of designing to ensure multiple and varying activities along the stråk. In addition, the stråk can be re-developed with outdoor activities such as community gardens, squares and playgrounds. The importance of supporting the establishment of outdoor activities and to assemble businesses along a stråk is a key design feature.

- …one has to try to assemble… we can not make the ground floor of all buildings everywhere filled with boutiques and I would also say that it’s not only boutiques, but it could be offices, real estate agents, architects, consultants of any sort, dentists or anything/…/ one can also consider businesses that interact between inside and outside on the ground floor, so one can pass between indoors and outdoors – that’s a good stråk.

In conclusion, the director of the department of strategic planning, emphasises that designing and constructing stråk is a way to support movement through the city; ‘Stråk populate the city /…/ just to create movement and make people come to places, that’s important.’ This definition of stråk partly references previous urban design approaches such as the ‘lively street’ (Jacobs, 1961), the importance of ‘assembling activities’ (Gehl, 1971) and the ‘urban corridor’ in new urbanism (Duany & Plater-Zyberk, 1993). But the concept of stråk includes both the lively street and the importance of activities, and, unlike the new urbanist corridor which is a specific section of a street, stråk comprises the notion of a continuous space that supports movement in two directions, a flow of people moving along it.

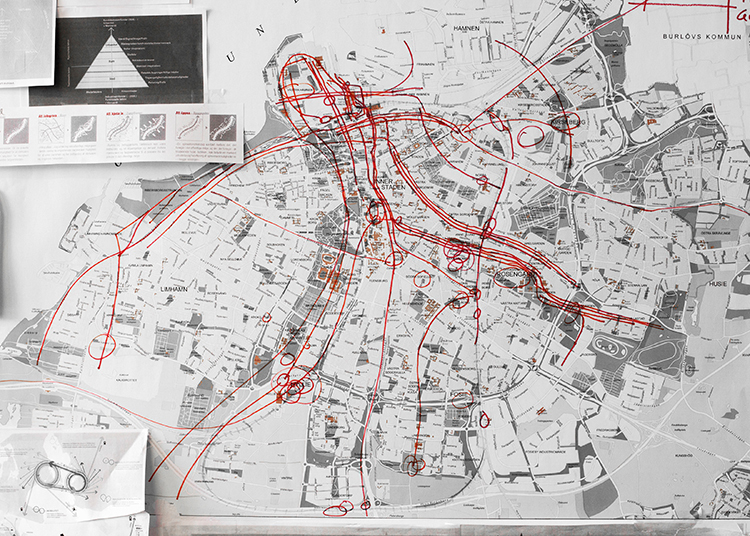

In parallel to the analysis of the interviews, two models were developed to visualise the notion of stråk as an urban corridor. The notion of a corridor is based in an understanding of urban design as a way to design spaces from a piece of clay, or a building mass (Carmona, 2010). In the models, the building mass is represented by simple blocks of wood and colour represents the stråk that runs and cuts through the building mass. In the first model [Image 2, left] the stråk is visualised as a street or route that leads through the urban fabric. Occasionally it covers the entire floor-scape between the buildings and occasionally it just leads past buildings and between squares and nodes. The second model [Image 2., right] visualises the notion that not only the floor-scape but also the walls along the street are included. Also here there is a variation. Solely the ground floors are included as part of the stråk in some parts and in others entire buildings along the stråk form part of the corridor. Together the two models aim to visualise one of the two determining features of the concept – the urban corridor.

2. Models visualising the notion of stråk as an urban corridor. Source: Author.

An Inter-scalar Connection

Linking places in the city and beyond, stråk are designed in support of connections. Stråk ‘connect districts’, ‘connect the city’ and ‘weave together the city’ according to the officials interviewed. In contrast to other existing concepts, stråk are inter-scalar; they connect the local shop-house to the main railway station and the city square, and, they lead to nodes from which one can connect to existing transportation networks running through and beyond the city.

According to the director of the traffic and roads department, the design of stråk should provide opportunities for people to move along the stråk, but also to linger in interesting places in different parts of the city. In line with this notion of moving between nodes, one design feature is that new buildings and new places should be located with a certain rhythm, or frequency along the stråk:

- If one talks about building an attractive stråk, something has to happen with a certain frequency and one should feel comfortable in staying there and feel safe.

This notion can be traced to ideas of the importance of visual permeability, that the view of places further ahead along a street or route makes urban space more attractive and may intrigue people to continue walking and to linger in interesting and complex places (Carmona, 2010; Cullen, 1961). The stråk thus serves as a connection between places that intrigues people to keep moving.

Stråk are also considered on a regional scale, as inter-scalar connections between Malmö and Copenhagen. The investments in infrastructure during the last decade (Malmö stad, 2010) has resulted in a finer network of connections according to the director of the urban planning department:

- …if we look at what’s happening now in the city, there’s so much happening with stråk, new stråk and patterns of movement and we consider that in connection to all the new infrastructure /…/ the movement pattern and all of these points in the city will be much more finely grained and also if you see it as an aspect of integration in the city and the region. If you connect it to the net of Copenhagen, which is also finer and becomes more finely grained, then that’s also more power in the regional integration.

One important role of stråk is thus to connect places and facilitate movement between them. In this sense, the stråk refers to a tradition of urban design approaches supporting movement along paths leading between nodes and focal points (Lynch, 1961). However, the notion of stråk also includes connections between places locally and regionally as well as between these scales. The stråk are linked together, forming a network from the local shop to the urban district, to a city and a region evoking an image of a network of movement.

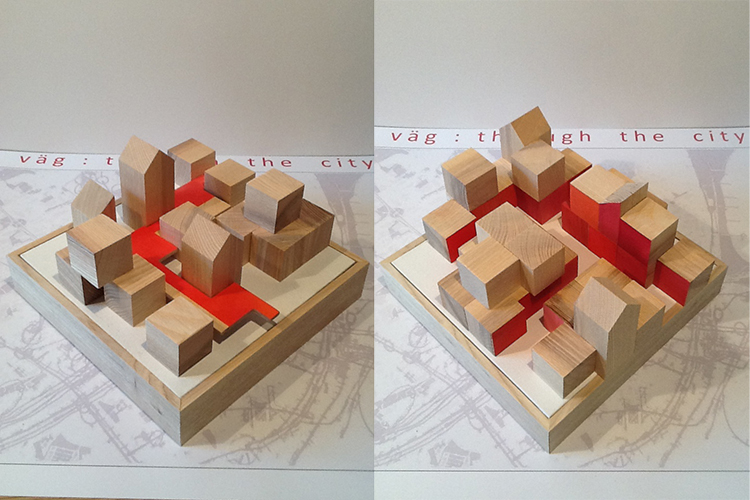

A second pair of models was developed in order to visualise the notion of stråk as an inter-scalar connection. The connections shown in the models are connections between places on the local and urban scale and connections on a regional scale, linking Malmö to Copenhagen. Again, simple wooden blocks represent the building mass and plastic cords represent the notion of connection. The first model [Image 3, left] visualises the notion embedded in the stråk concept of connecting places locally and between districts or nodes on a citywide scale. On one side of the model, the building mass represents the local scale, which could be places in the neighbourhood or district. Here the cords connect places of significance locally. On the other side of the model signature buildings and important nodes, such as the Turning Torso are visualised, and cords run between the local scale and the important nodes of the city. The second model [Image 3, right] represents connections on a regional scale, between Malmö and Copenhagen. Together, the two models aims to visualise the second of the two determining features of the concept – the inter-scalar connections.

3. Models visualising the notion of stråk as an inter-scalar connection. Source: Author.

Verbal and Visual Approaches in Research

This article has suggested that visual material can, in combination with other empirical material such as interviews, be part of the analysis and interpretation in the process of defining an urban design concept. It should be noted that the findings presented here are the results from a process that has included several previous sketches, models, themes and possible interpretations. A key issue is that the verbal and visual approaches have been parallel practices in the entire research process.

The findings presented in this article should be interpreted as a first attempt in the endeavour to more closely connect verbal and visual approaches in research. Certainly, more questions than answers arise and many questions remain to be answered and further debated. One is the choice of material and their relation to the issue researched. In the case of stråk, the reason for designing models is based on models as a traditional tool in architecture and urbanism. Of importance is also that physical models are a way to visualise analysis (Crowe & Laseau, 2012), i.e. to deliberately select only a few features to be included in the final work. In this case, wood, colour and cords were selected to visualise the two features included in the stråk-concept: the urban corridor and the inter-scalar connections. In addition, models afford ‘visual literacy, they can be held in one’s hands and scrutinized from the street-level to the bird’s-eye view. This is important since visual literacy is one of the basic skills in architecture and several other design professions and research fields that also can be used in research. Another important question is the role of visual material as communication devices. The models in this article have been exhibited on several occasions, for example in exhibitions of urban research (Grundström, 2015), and, they have been used in education. As material objects, they are tools that can be seen and scrutinized by academics, students, professionals and the public and thus promote public debate. Experience from the exhibitions shows that models invite visitors to talk about urban design and reflect on urban development. A third important question, and likely the most important one, is related to the similarities and differences between verbal and visual approaches in research. I would argue that the research process holds several similarities. Here, ‘abstraction’ comes to the fore, since extracting verbal themes from interviews or extracting visual themes to be presented in models are in many ways, similar processes. One possible reason for this similarity is the basis in ‘abduction’, which is used in social science as well architectural and design research (Cross, 2011; Johansson, 2000). In abduction, the researcher is open to ‘surprising facts’ and can shift between deduction from existing theories and induction from empirical verbal and visual material. This has contributed to a creative and productive research process challenging existing understandings (Asplund, 2004) and it has also contributed to furthering the analysis and the interpretation of the results. But even though the process of research has similarities, the outcome still differs; the result from verbal approaches is presented in text and the result from visual approaches is presented in maps and models. Reading the results, thus requires both traditional literacy as well as visual literacy. This is a challenge but also an advantage since researching through both visual and verbal approaches shows the same results but in different forms.

In sum, the visual and verbal approaches in the research on stråk both contributed to the analysis and interpretation of stråk as an urban design concept. The questions of what contributions visual and verbal approaches respectively can make is a fundamental issue for future research. To what extent are the respective approaches, and visuality (Mitrović, 2011) in particular, helpful in the ‘description, interpretation and explanation’ (Hartman, 1998) of the built environment, required in theorisation and conceptualisation? In the coming decades the ‘material turn’ in research is likely to have an increasing impact on architectural and planning research. Thus, including visuality, as in this case creating models, can be one productive and creative way forward.

References

— Asplund, Johan (2004). Hur låter åskan: förstudium till en vetenskapsteori, [How does thunder sound: pre study of a theory of science]. Bokförlaget Korpen.

— Belardi, Paolo (2014). Why Architects Still Draw. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

— Berkel, Ben van & Bos, Caroline (2007). UN Studio. Design models, Architecture, Urbanism, Infrastructure. London: Thames & Hudson.

— Bryman, Alan (2008). Social Research Methods. Oxford: University Press.

— Bjerre Hjortenberg et.al. (2012). Show me Your Model. Copenhagen: Danish Architecture Centre.

— Carmona, Mathew (2010). Public Places – Urban Spaces: the Dimensions of Urban Design. Oxford: Architectural Press/Elsevier.

— Cross, Nigel (2011). Design Thinking. London: Bloomsbury.

— Crowe, Norman & Laseau, Paul (2012). Visual Notes for Architects and Designers. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons.

— Cullen, Gordon (1961). The Concise Townscape. London: Butterworth Architecture.

— Duany, Andres, & Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk (1993). ‘The Neighborhood, the District and the Corridor’. In The New Urbanism: Toward an Architecture of Community, xvii- xx, edited by Peter Katz and Vincent Scully. New York : McGraw-Hill.

— Flyvbjerg, Bent (2006). ‘Five Misunderstandings about Case-study Research.’ Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245.

— Gehl, Jan (1971). Livet mellem husene, udeaktiviteter og udemiljøer [Life between Buildings]. Copenhagen: Arkitektens Förlag.

— Groat, Linda & Wang, David (2002). Architectural Research Methods. New York: Wiley & Sons.

— Grundström, Karin (2014). Stråk mellan öst och väst, Stadsbyggnad i ett föränderligt stadslandskap [Pathways between East and West: Urban design in a polarized urban landscape]. In Listerborn & Grundström et. al. (Eds.). Strategier för att hela en delad stad. Samordnad stadsutveckling i Malmö [Strategies to heal a divided city: coordinated urban development in Malmö]. Malmö: Malmö University.

— Grundström, Karin (2019). ‘Planning for Connectivity in the Segregated City’, Nordic Journal of Architectural Research. Theme issue on ‘Architectural Transformation of Disadvantaged Housing Estates in the Nordic Countries’, Vol.1: 2019 pp 9-32.

— Hartman, Jan (1998). Vetenskapligt tänkande [Scientific Thinking]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

— Jacobs, Jane (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

— Johansson, Rolf (2000). ‘Om abduktion, intuition och syntes’ [On abduction, intuition and synthesis]. Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 3. Göteborg: OFTA Grafiska.

— Kvale, Steinar (1997). Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun [The Qualitative Research Interview]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

— Lynch, Kevin (1961). The Image of the City. Cambridge: M.I.T Press.

— Malmö Stad (2010). Rosengårdsstråket, Report Series. Malmö: Gatukontoret.

— Mitrović, Branko (2011). Philosophy for Architects. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

— Norstedts (1988). Norstedts Svenska Ordbok. Stockholm: Norstedts.

— Persson, Rickard (2004). Some thoughts on Stråk. Space and Culture, 7 (3): 265-282.

— Schmmidt, Hammer, Lassen (2012). ‘The international criminal court in The Hague’, presentation in Eds. Bjerre Hjortenberg, Nana et.al. Show me your model. Copenhagen: Danish Architecture Centre.

— Weiwei studio & Herzog & De Meuron (2011). ‘Ordos 100’, in Eds. Juul Holm, Michael et. al., Living. Frontiers of architecture III-IV. Humlebeck: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art.

— Wikström, Tomas & Lina Olsson (2012). Stadens möjligheter: platser och stråk [The City’s opportunities: places and pathways]. Malmö: Region Skåne.

Exhibitions

– Grundström, Karin (2015). ‘Stråk as an urban design concept’. In (Curators) Grundström, Karin & Rundgren, Katarina, Staden Studerad/ City Check, Exhibition of five research projects (November 2014 – January 2015). Malmö: Form/Design Center.

+

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (FORMAS) under Grant Number 250-2010-371.

Karin Grundström is an Associate Professor in architecture at the Department of Urban studies, Malmö University, Sweden. Grundström holds a PhD in architecture from Lund University and is a chartered architect. Her research comprises both the dominant organisation of space and place, as well as people’s everyday resistance and experience of the city. She has published in the areas of urban design and planning, housing and segregation and has curated and participated in exhibitions on urban research.

Volume 3, No. 2 June 2020