The street market as animated space: an ethnographic exercise

– Christopher Adan

Sayed1

Sayed wears a red windbreaker and looks me straight in the eyes. His stall is replete with duvet covers, pillows and mattress foam. Originally from Bangladesh, he has been vending at Chapel Market for 8 years. His wife, son and extended family live here. A £4,000 investment went into his stall. At first, he sold stationery but failed to realize much profit. Convenience and grocery stores sold the same products for less. He was not protected by insurance, and bad weather would ruin his inventory. He carries his risk with him. He pays out of pocket for wholesale stock from China and moves it on piecemeal over the following months.

He transitioned to bedding and rugs, pillows and the like, searching for profit. With this he gestures to finely stitched and patterned pillows prominently displayed on his stall. He has a company with his brother in Bangladesh who hand-makes them but confides that they are not selling well. Production costs and import regulations are too much. And so, after this stock moves he does not know what he will sell.

He stays in London because he is his own boss, dictating his schedule even though it sees him work 6 days a week, meeting suppliers on the 7th. He intimates that he still can’t pay himself even 50 pounds per day. He misses home, but to return he would have to pay for relocation and invest in a new business. He is a businessman, he tried bicycle food delivery and quit after a month because he didn’t like London’s traffic and felt ill in the exhaust fumes. As a driver for these companies you are on your own, and he quit when he started to feel sick, returning to the market full time.

Now he is here every day, waiting to sell, while his business is dwindling. He doesn’t see young people come to the market anymore; instead they stay at home and order online. He faces harsh competition from online and fixed stores, observing that market patrons are older, seeking tradition and nostalgia. The market has been around for more than 100 years, but now he sees it decline. In 5-10 years, he fears nobody will come.

Sayed has friends scattered around London but doesn’t have time to see them. His cousin won the visa lottery and took his whole family to New York where they run a Subway sandwich franchise. Sometimes he sees pictures of the family home. ‘They are rich now’, but he also thinks his cousin is unhappy because he has not been messaging as much recently. Still, he believes his cousin has been lucky. We are interrupted by an elderly couple who need something in King size.

1. Shoppers pick through a produce stall. Photo Credit: Wei Jia Lim

Animated Market Space

Coursing through the market are people of incredibly diverse nationalities, ages, and styles of fashion. Everywhere parents push buggies with young children. You see wanderers, tourists with large backpacks and that surveying, appraising gaze, camera on strap, guidebook clutched in hand. A British lady is in a flowery dress, laptop by the open café window. A well-dressed couple in button-up shirts enjoys their lunch. The shop boy speaks Italian into the phone; cocktails marinate in large glass jugs. Both vendors and clientele possess varied backgrounds, languages and affectations, from Bangladeshi migrants to the local produce vendors bellowing, ‘large strawberries a pound, large strawberries.’ Unfamiliar languages swirl between stalls. The elderly gentleman in a tidy green sweater paces across the street while his wife browses; the tracksuit father snaps photos with his phone while his son kicks a neon football.

Rent is £65 per week, extra for access to storage space. Stalls prominently display license cards. Three large men with clipboards wearing Islington jackets make their way down the market street, politely nod to the produce vendor and scrutinize the proffered folded blue licensure slip. One stall’s sign promises all range of electronic expertise. Some vendors name their stalls with professional banners and some are more informal, with hand-written menus and notices. The Family Butcher hand-makes his sausages in Hartford, nearby his home, and says he has been here for 10 years. Business is good, ‘surviving’ he says with a smile. Ask the homewares vendor where he sources his merchandise, he laughs and with another smile, ‘China.’

2. Electronics/Accessories stall. Photo Credit: Wei Jia Lim

3. Homewares stall. Photo Credit: Wei Jia Lim

These spaces instantiate endless interactions of varying length and depth. A young woman dressed in expensive clothes jumps, running to greet the man in army fatigues with a hug. He carries a large backpack and another on his front. She returns to her friend explaining ‘sorry, one of the homeless guys I work with.’ The florally-dressed lady asks the man behind the counter, ‘do you have Wi-Fi?’ He laughs, walking over a slip of paper. The elderly woman, a clear regular, sits at a shaded table, eats a salt beef sandwich and smokes a cigarette, chatting with a woman, a stranger, at another table. People stop, meet, greet, comment on the weather, exchange pleasantries, ‘she’s fine, how about yourself?’ A parka-dressed young man buys a pipe from the homewares vendor. They exchange money and part ways, the vendor returns to his stall. He notices the pipe boy is back, testing out lighters. He buys two. They part ways with knowing smiles.

Beyond curt nods and brief pleasantries between the shop worker and the gentleman in blue mirrored sunglasses, the fixity and repetition of the market molds and shapes the interconnected sociality of the market space. The homewares vendor shares a laugh with the man next door who sells women’s clothes. The blue-haired British waitress carries a tray of food across the street from the Mercer and Co., beelines into the Fruit and Veg and returns promptly without it. A remarkable show of solidarity as she half-jokes to the owner, ‘if you ask me, the boys in Chapel get spoilt too much.’ The proprietor of the Fruit and Veg carries stacks of empty cardboard boxes, refuse from the day’s sales, arranges them on the sidewalk, pauses and peers into the Star Express, giving someone a thumbs-up before walking back inside to continue the chore. Ceramics stall owners relax in the waiting van, chatting and drinking from large green cans as they wait to pack their wares.

The market space is temporally charged. It is the site of a regular morning rush which transforms bare street to vibrant commercial hub. The ceramics stall takes shape as stock is unloaded, first forming a table with plastic crates, emptying them of merchandise for display. People shift from street to sidewalk and back, discerning looks as they inspect goods hoping not to seem too interested. Three tourists stop to take pictures of the landmark façade of the M. Manze, famous provider of live and jellied eels since 1902. Well into closing time, rusted wheeled metal cages linger, rigid beasty things rendered bare by the passing of the day. Soon they join the afternoon parade down White Conduit Street of rumbling carts stacked with goods and building materials. Two women negotiate their way around piles of debris left behind after the flower stall. This pile of refuse and flowerpots is the only trace of the stand which stood there minutes ago. A pigeon swoops around the garbage truck, lights flashing as the garbage man in neon vest and salmon polo shirt rolls the dumpster down White Conduit Street. A popular dance song emanates from the gift wrap stall.

Approaching Chapel Market

Steeped in history, Chapel market in Islington remains bustling to this day. To some, market life is struggle. To others, it is opportunity. Some face uncertain futures and others are happily ‘surviving’. A snapshot of the market can illuminate, with limitations, fascinating striations which coexist in urban space. This ethnographic exercise uncovers elements of informality and precarity within an urban street market, but also points to the risk of distilling human sociality into a strict formal/informal binary. In doing so, it lends a new voice to conversations around the sociological analysis of everyday urban spaces. In the context of London, situated in the so-called global North, this study illuminates the reality that elements of informality coexist alongside more regulated practices even outside of Southern cities, but more so than this spotlights the problematic nature of striking dualisms in the examination of human social life. Our activities are significantly more complex than black-white distinctions and we must acknowledge this in our conceptualizations of public use of urban space.

In such light, the paper argues two points. First, that street markets can be read as Amin (2015)’s animated spaces where diverse groups of people comingle, but also interpose a level of superfluity between consumer and vendor, a veil which requires time and effort to pierce beyond the transaction and achieve a deeper interpersonal connection. Second, that in the context of market actors and beyond, shoehorning market practices into a formal/informal binary is problematic and there is need for a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena. The economic success of market vendors depends on their ingenuity, strategy, and decision-making ability, but also on the whims of their customers, hierarchies of other vendors, interrelations between market actors and authorities, historical context, and the influence of macro-structural forces. Following this introduction, the paper historicizes Chapel market, reviews literature on animated space and urban (in)formality and discusses the ethnographic material in that context.

History

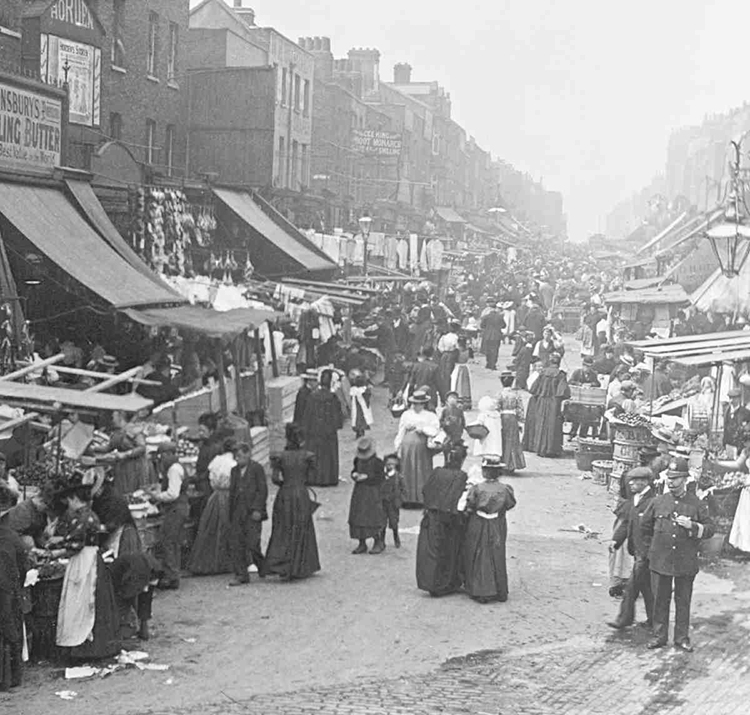

Chapel Market lies in Islington, London’s second smallest borough. By the time Islington was formed, it had undergone several hundred years of history and become a ‘thriving but threatened’, ‘traditional and unpretentious’ public market (Smith 1999; HL n.d.; TL n.d.). The first businesses appeared in 1841. By 1879, Chapel was officially designated as a street market [Image 4.], complete with fruit stalls, shop fronts, clothing sellers, and complaints from residents about the daily butcher’s stall (Temple 2008; HE n.d.; HL n.d.). It has been variously portrayed as a nuisance, as possessing ‘working class character’, or constituting a ‘commercial artery in a district of spreading poverty and squalor’ (Temple 2008; HL n.d.).

4. Chapel Market; 1898. Source: BH n.d.

Chapel Market was the site of Sainsbury’s first branch in 1882 and Marks & Spencer’s Penny Bazaar in 1914, earning it for some a ‘particular place in the history of British shopping’ (Temple 2008; HL n.d.; HE n.d.). It has since been designated a conservation area and possesses space for 160 pitches, supports 85 licensed traders, hosts Islington’s Sunday Farmers’ Market, and ‘can fairly claim to have retained its historical character essentially intact’ (IC n.d.; LFM n.d.; HE n.d.). Unfortunately it has never quite escaped its checkered past, described today as both ‘going strong’ and in decline depending on who you ask (LFM n.d.; Sayed; HL n.d.). Regardless of the market’s future, it remains the site of ‘bellowing, clattering traders’. Currents of activity, browsing, and the entangled fortunes of stall vendors flow through here [Image 5; Image 6. TL n.d.].

5. Chapel Market; 1970. Source: BH n.d.

6. Chapel Market Today. Photo Credit: Wei Jia Lim

The Street Market Read as Animated Space

In places where multiple actors occupy space, such as Chapel Market, a broad opportunity sphere forms enabling interaction, negotiation, tension or harmony between strangers placed in proximity. In these gathering places, these places that place in juxtaposition various ‘temporal and spatial logics’ employed by a sea of individuals, meaning and connection are fluid and can arise as needed (Massey 2005). For example, a busy street market is rife with transactional and interpersonal interaction which ebbs and flows as described in Amin’s account of animated spaces (Amin, 2015). What manifests and dissipates in animated spaces like the street market are common ‘landscapes’ that catalyze targeted, and less so, interactions between people who may not have had cause or opportunity to interact before (Chambers 2013: 5). These spaces are linked to ‘the choreography of bodies and to the atmosphere of place’, becoming wholly dependent on qualities that are variable in nature such as time, and chance, and the random friction generated by people moving about en masse where goals and opportunities are not necessarily shared at first but may briefly become to be over time (Amin 2015: 240). When the public location becomes an event in and of itself, based on a common, temporal ‘ethic’, spaces such as this are dynamic in nature and overlay the sort of rich, textural meaning valorized by the everyday urbanist (Chase, et al. 1999; Amin, 2015: 240).

7. Activity at a Fish stall. Photo Credit: Wei Jia Lim

Scholars have touched significantly on the fluidity and choreography of street markets in past literature. Whether analyzing strategies and rituals in a Taiwanese night market on the fringes of legality through Goffman’s lens of performativity (Goffman, 1959), exposing the interplay of market regulation, governance and political economy, or analyzing the place of informal market practice in relation to government authority and more formalized economies, there are a few points of common reading which run throughout (Smart 1989; Tai 1994; Yu 1995; Xue and Huang 2008; Yeo, et al. 2012; Chiu 2013). It is little contended that street and night markets blend practices that may be seen as formal and informal. Many agree that markets can be read as a series of interrelating rituals and performances that rise and fall with the sun. Further, the economic fortunes of market actors depends on a series of factors from individual strategy to historical context and the influence of macro-structural forces.

What is important to take note of in addition to these foundational premises is both the risk of dichotomizing a rigid framework which fails to appreciate nuance between the modes ‘formal’ and ‘informal’, and the need to reconceptualize our readings of animated space outside of a North/South binary. Indeed, in recent years there has been greater effort by scholars to bring this imbalance to the fore through study and ethnography of markets in cities such as Chicago, New York, or London (Morales et al. 1995; Wasserman 2007; Watson 2009; Rhys-Taylor 2013). And the study of informality has increasingly evolved from roots in the urban un/underemployed to a shared urban issue worthy of critical analysis (Hart 1973; Ferman and Ferman 1973; Castells and Portes 1989; Sassen 1991; Robinsin 2006). In light of this, greater work can be done towards understanding human sociality through the study of the street market as animated space in a global context.

This ethnography of Chapel Market in Islington uncovers an animated space replete with its own actors, history, currents of activity, and interrelations with authorities and with government. There is a clear dynamism here which resists reduction into a dualism of ‘formal’ and ‘informal’. Instead, it spotlights the need for an appreciation of the shades of gray that exist between these two conceptualizations as realities vary from actor to actor, vendor to pedestrian. Aligned well with this aim is the perspective of the everyday urbanist, which privileges mundane sites and spaces as being rich with meaning and potential insight (Chase, et al. 1999; Kelbaugh 2000). By taking analysis to the ground level through exploration of a busy street market, speaking with vendors and passers-by, the scholar becomes part of the animated space and themselves perpetuates the sparks of activity which characterize these locations. These conversations and interactions constitute the territory for analysis and by digging deeply into them we can achieve a better understanding of our social worlds.

(In)formal Geographies

Much scholarship concerning the street market focuses on Southern contexts. However, just as in the markets of Thailand there are clear signs of the at-times chaotic nature of public, animated space in the so-called global North. What is different is that there may be a layer of more regulated, orderly practices overlaid on undercurrents of less formalized activity. There emerges a need to appreciate the nonbinary individuality of public market actors. In pursuing economic success, their praxis becomes irreducible to simple distinction between formal/informal, instead shifting regularly along a spectrum whereby any given action is not limited to qualities of either. This is evidenced by the strategies employed by market actors and the nature of market regulation itself, modulated as life flows throughout the day.

Strategies

A glance at the market space reveals multitudinous strategies employed by shoppers and vendors alike to negotiate and manage the market experience. Customers haggle, or briefly distract vendors to snatch a lighter and hurriedly light a cigarette before departing. Sayed makes constant calculations and rational decisions as an incidental part of his day, determined to predict the shifting market sentiment. He responds to his own unique portfolio of risks. He values the freedom of being his own boss but struggles to make profit and is unsure of his next move. This uncertainty looms like a specter threatening to take food off his family’s table. He stays for lack of clear opportunity elsewhere and develops a dynamic, individualized program of action based on his analysis of a host of factors. His future is unpredictable, his decisions are based on fragmented information.

Regulation

For Sayed, and many other vendors in tenuous positions, less formalized activity occurs simultaneously with regulated practices and daily life renders boundaries between the two distinctions unrecognizable. Indeed, activities formalized by the state and actions that are less formalized are interdependent and inseparable (Ferman and Ferman 1973; de Bruin and Dupuis 2000). Uniformed representatives in city jackets verify if vendors have attained the right to be present. This gentle policing reminds actors of the constraints imposed by the council on access to market space. To claim their position, vendors undergo a series of rituals and licensure activities such as rent payment and documentation. Alongside this, however, the market actor has a certain degree of freedom of self-determination in terms of their inventory and sales practices. On an individual level, actors at times play by the rules, but at others devise their own methods to attain their goals. Sayed imports pillows made by his brother in Bangladesh. He confides that he could evade government import duties, but he chooses not to for moral reasons. He contributes to the NHS and national insurance. In this small example, he operates on the fringe of regulated space, checking certain boxes but at the same time pursuing his own ends which shift according to many variables. His strategies may evolve according to changes at many scales, from national policy change, to his perception of overall market performance, to the health outcomes of himself and his family.

8. Rugs for sale. Photo Credit: Wei Jia Lim

Flows

This fluidity of future and fortune is clear in the daily flux of the market outside of Sayed’s story. The ceramics stall is built and broken down, merchandise arrayed on the very containers they are stored in. This strategy saves vendors time and money, ensuring that as they pack away the merchandise, they break down the stall. While they are ostensibly not in danger of being abruptly policed as is common in many street markets in the so-called global South, it reminds us again that animated market space is charged with a dynamic temporality. From sidewalk to buzzing commercial artery and back again each day, the street market is for many a stop along the unpredictable path to economic success. Uncountable personal histories, backgrounds, interests and motivations coalesce along this street as it transforms over the course of the day. It is animated space in the truest sense, where volumes of actors spend time ensconced within their private spheres of intention except for those moments occasioning the need to interact across a common landscape, make purchases, or chat about the weather.

Reflections

A busy street market is a prime location to reconceptualize animated space from an everyday perspective and add novel viewpoints from the global North to a typically Southern-dominated paradigm. Digging critically into the everyday strategies of market actors and the flows of the market itself as a public event reveals a deep interplay of forces, response, and interactions. Furthermore, the diversity and dynamism of market activity lends credence to the argument that informality is a shared urban issue and a reductive cast of work as stringently formal or informal fails to capture the true nuance and breadth of market praxis (Robinson 2006; Varley 2013). Strategies and performance are not limited to a strictly formalized relation with the state or complete lawlessness but instead can assume various degrees of formalization and shift readily in this distinction according to the goals of the actor. Study and ethnography of the everyday animated public space uncovers the rich textural nature inherent in human social life. Appreciation for this complexity and acknowledgement that it is problematic to reduce social phenomena into dualisms can have significant positive implications for actors in semi-precarious positions in terms of policy improvements and public debate.

The depth and strength of the conclusions of this research will benefit from longer-term study. This project illuminated a thousand initial threads to the tapestry which constitute Chapel Market, each deserving to be unraveled into a deeper and more complex story. It paints a limited picture of market life with implications for the public uses of urban space. Further work could incorporate deeper interactions with customers and employees of the fixed stores that line the market. Moreover, it is important to pay sociological attention to other dimensions beyond economic success, such as community, friendship or solidarity, especially in cases where marginal or migrant vendors lack adequate existing social support networks. Future study can build on a strong base of multiculturalist thought and speak to these issues (Watson 2009). Broadly, lessons can be drawn from this work into our study of other everyday contexts which generate interaction and activity between people and can be read as animated space (Amin 2015). For example, scholars can go explore the local mall, the public park, the train carriage, and draw equally deep and interesting insight into human sociality. Importantly, new volumes of everyday research improve our ability to bridge the North-South theoretical divide and establishing common ground from a global perspective.

Notes

1.Name altered for anonymity.

References

— Amin, A. (2015) ‘Animated Space’, Public Culture, 27, 2, pp. 239-258.

— Chiu, C. (2013) ‘Informal Management, Interactive Performance: Street Vendors and Police in a Taipei Night Market’, International Development Planning Review, 35, 4, pp. 335-352.

— Castells, M. and Portes, A. (1989), ‘World underneath: the origins, dynamics, and effects of the informal economy’, in A. Portes, M. Castells and L. A. Benton (Eds.), The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries, Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press, 11–40.

— Chambers, I. (2013) ‘Mediterranean Blues: Musics, Melancholy, and Maritime Criticism’, Mimeograph, Università degli Studi di Napoli “l’Orientale”, Naples, Italy.

— Chase, J., Crawford, M., and Kaliski, J. (Eds.) (1999) Everyday Urbanism, New York, Monacelli.

— De Bruin, A., and Dupuis, A. (2000) ‘The Dynamics of New Zealand’s Largest Street Market: The Otara Flea Market’, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 20, 1-2, pp. 52-73.

— Dovey, Kim. 2012. “Informal Urbanism and Complex Adaptive Assemblage.” International Development Planning Review 34, no. 4: 349–68.

— Ferman, P.R. and Ferman, L.A. (1973) ‘The Structural Underpinnings of the Irregular Economy’, Poverty and Human Resources, 1, pp. 3-17.

— Goffman, E.T. (1959), The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, New York, Doubleday.

— Hart, K. (1973) ‘Informal Income Opportunities and Urban Employment in Ghana’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11, 1, pp. 61-89.

— Hidden London (HL) (n.d.) Chapel Market, Islington, viewed 17th April 2017,

— Historic England (HE) (n.d.) Chapel Market N1 – Islington, viewed 17th April 2017,

— Islington Council (IC) (n.d.) Chapel Market, viewed 17th April 2017,

— Kelbaugh, D. (2000) ‘Three Paradigms: New Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism, Post Urbanism – An Excerpt From The Essential Common Place’, Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 20, 4, pp. 285-289.

— London Farmers Markets (LFM) (n.d.) Islington Farmers’ Market, viewed 17th April 2017,

— Massey, D. (2005) For Space, London, Sage.

— Morales, A., Balkin, S., and Persky, J. (1995), “The Value of Benefits of a Public Street Market: The Case of Maxwell Street’, Economic Development Quarterly, 9, 4, pp. 304-320.

— Rhys-Taylor, A. (2013) ‘The Essences of multiculture: a sensory exploration of an inner-city street market’, Global Studies in Culture and Power, 20, 4, pp. 393-406.

— Robinson, J. (2006), Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development, New York, Routledge.

— Sassen, S. (1991), The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

— Smart, J. (1989), The Political Economy of Street Hawkers in Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Centre of Asian Studies, The University of Hong Kong.

— Smith, C. (1999) The Market Place and the Market’s Place in London, c. 1660 – 1840, PhD Thesis, University College London, London.

— Tai, P. F. (1994), ‘Shei zuo tan-fan? Taiwan tan-fan de li-shi xing-gou’ (Who are vendors? The historical formation of vendors in Taiwan), A Radical Quarterly in Social Studies, 17, 121–48.

— Temple, P. (2008) ‘Penton Street and Chapel Market Area’, in Temple, P. (Ed.) Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, London: London County Council, pp. 373-404. British History Online, viewed 17th April 2017,

— TimeOut London (TL) (n.d.) Islington Farmers’ Market, viewed 17th April 2017,

— Varley, A. (2013) ‘Postcolonialising Informality?’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31, pp. 4-22.

— Wasserman, S. (2007), ‘The triumph of commerce over community: a look at New York’s generic street fairs’, in J. Hammett, K. Hammett and M. Cooper (Eds.), The Suburbanisation of New York, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 87–96.

— Watson, S. (2009), ‘Brief Encounters of an Unpredictable Kind: Everyday Multiculturalism in Two London Street Markets’, in Wise, A. and Velayutham, S. (Eds.) Everyday Multiculturalism, London, Palgrave, pp. 125-139.

— Xue, D. S. and Huang, G. Z. (2008), ‘Regulation beyond formal regulation: spatial gathering and surviving situation of the informal sector in the urban village case study of Xiadu, Guangzhou’, Geographical Research, 27, 1390–97. [Chinese]

— Yeo, S. J., Hee, L. and Heng, C. K. (2012), ‘Urban informality and everyday (night)life: a field study in Singapore’, International Development Planning Review, 34, 369–90.

— Yu, S. D. (1995), ‘Meaning, Disorder and the Political Economy of Night Markets in Taiwan’, PhD dissertation, University of California, Davis.

Christopher Adan has a BA in Sociology from the University of Washington and an MSc in Urban Studies from University College London. He currently works as research assistant with CNN Brand and Multiplatform Research in New York City.

Volume 2, No. 2 October 2019