City of the many

– Max Ott, Norbert Kling and Christian Zöhrer

1. The city as a common good

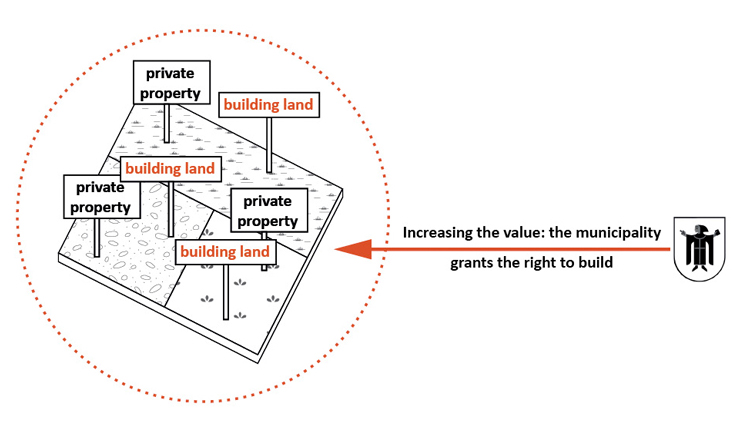

The city of Munich has recently held an ideas competition for a 600 hectare site in the northeast of the municipality, which is characterised by a mix of suburban housing, agricultural uses and horse riding facilities [Image 1]. The task was to develop three scenarios for its future development, comprising commercial and residential uses together with public infrastructure. The competition brief was limited to delivering fixed master plans while important questions regarding land policy and long-term planning processes were left out. However, if we understand the city as a common good, such fundamental questions must not be neglected. Therefore, we have sketched out a path towards a production of urban spaces that shall be accessible for as many people as possible [Image 2].

Image 1. Project area in the North-East of Munich. Source: Authors.

Image 2. The model illustrates the proposed spatial framework and possible outcomes of the process-oriented approach. Source: Authors.

2. Munich under pressure

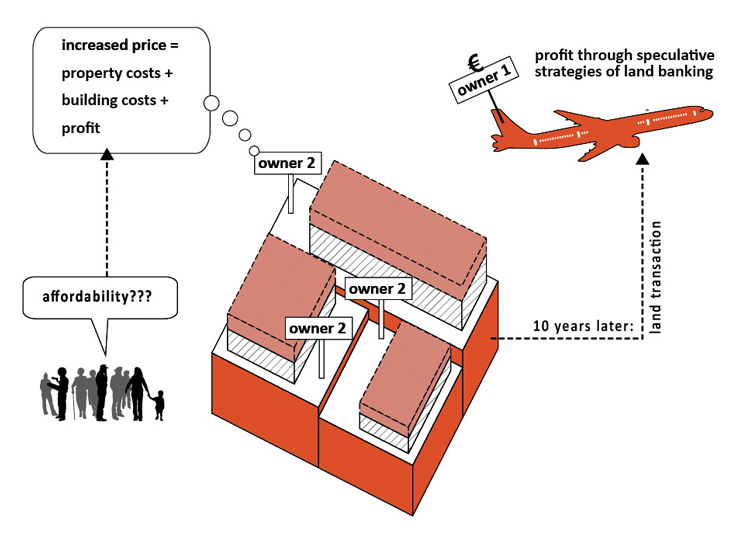

Munich had 1.557 million inhabitants in the year 2017 and its population is estimated to increase to 1.850 million inhabitants by 2040. Municipal land reserves are dwindling, while the high demands for new housing cannot be met. As a response, actors in politics, the planning disciplines and the building industry are recurrently calling for “building, building, building”. This proposition overlooks a fundamental issue: The property market is optimised for the profitability of capital investment because it is primarily based on the interdependence of limited land supply, increasing demands, and the exclusive right of property owners to realise profits arising from land rents. As a consequence, as with any real estate sector whose actions are determined by the maximisation of returns or fast profits, it will seek to push sales values. This condition is the main driver of the rising costs of housing, commercial space, as well as social and cultural infrastructure. It also helps us understand why a considerable number of people in a wealthy city like Munich are facing old-age poverty and are threatened in an existential way by rent increases, or why small businesses have to relocate to other areas [Image 3].

Against the background of this citywide problem, the main challenge facing Munich’s Northeast is not to build ‘at whatever cost’. It is rather to provide the maximum amount of affordable and permanently available spaces for all sorts of uses and thus to respond to this question: ‘Who owns the city?’ This challenge requires addressing the problem of land speculation.

Image 3. Munich under Pressure. (A poster for the municipal election held in spring 2020 says: “Munich belongs to all of us. Not the speculators”). Source: Authors.

3. Property Issues

Even though land is a finite resource and at the same time an indispensable prerequisite to participate in everyday life, it is treated as a commodity – individuals and corporations are entitled to its ownership, they may trade it like any asset or convert it into a financial instrument. Inequality is both cause and effect of commodification. This becomes most visible where plots of land are particularly scarce and in high demand: In Munich, for example, values for building land have increased by no less than 36,000 percent since 1950. Due to their exclusive entitlements, landowners have profited from this valorisation, again and again. The costs arising from these profits are paid by those who do not own the land but need to use it in one way or the other. Their financial burden further increases whenever investment strategies like land banking purposefully postpone any building activity. Here, capital gains on land transactions are realised after a period of ten years, when speculative property sales cease to be taxed. The unearned increment increases the cost of land and thus the cost of its financing, which is passed on to the following generations of potential land users [Images 4, 5, 6].

Image 4. The starting point of speculation: private property and building rights. Source: Authors.

Image 5. The private appropriation of surplus value of urban land is a main driver

of rising costs for housing, commercial space, as well as social and cultural infrastructure. Source: Authors.

Image 6. The former mayor of Munich, Hans-Jochen Vogel in 1972. Source: Authors.

4. Municipalisation and leasehold (Erbbaurechte)

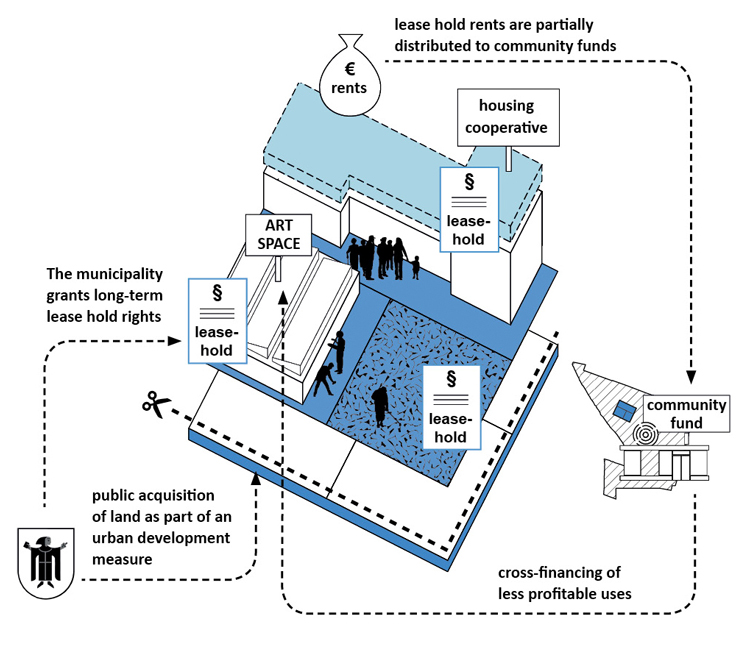

What is the response to this domination of exchange value over use value? We propose that the land in Munich’s Northeast should form the basis of a different value-added process, which offers more democratic and open forms of participation. For this purpose, the legal instrument of an urban development measure (‘Städtebauliche Entwicklungsmaßnahme’, or ‘SEM’) as defined in the German Federal Building Code may be used for the public acquisition of land at a price below the market value. To ensure that such a measure facilitates sustainable access to the use of land for economically less potent actors, the publicly acquired land has to remain in the hands of the municipality. This is why it should grant leasehold rights (Erbbaurechte) only. The basic principle of the leasehold system is simple: the legal ownership of a plot of land is separated from the buildings and uses in a first step and then recombined in a contractual second step. The leaseholder is granted the rights to construct buildings and use the land over a long period, without having to make a high one-off payment for acquisition, as the actual land ownership remains with the other contractual party. In return, the leaseholder pays an annual rent for the right to use the property.

This system could establish the basis of an urban development policy that is explicitly orientated towards the common good. Firstly, because annual ground rents ensure that the surplus value of urban land, which is the collective product of the urban population as a whole, is effectively and permanently redistributed to the urban polity. Secondly, by means of charging a variable rent, initial hurdles may be reduced for building projects that operate on the basis of low revenues – in this way the leasehold system supports actors with positive social impacts. And thirdly, because criteria of affordability can be established by the leasehold contracts that significantly exceed the statutory levels and periods as defined in the federal social housing act.

5. Negotiation processes

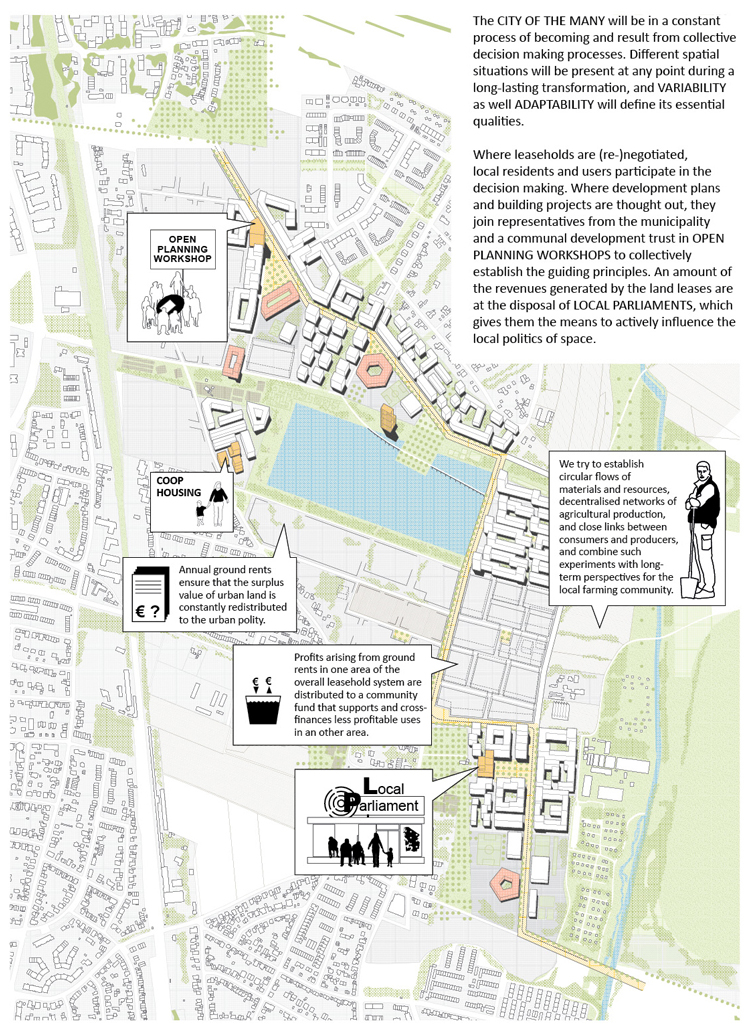

More specific opportunities arise if the leasehold system is implemented in the development process of Munich’s Northeast [Image 7] and if this process is explicitly understood as a long-term collective negotiation process between the city administration, planning experts, property developers, housing cooperatives, urban dwellers as well as local residents and initiatives:

- It may help to ensure a much more finely grained democratisation of land development, because the municipality as a landowner is accountable for its actions to the urban public.

- It creates the opportunity to distribute profits arising from ground rents in one area of the overall leasehold system to a community fund that supports and cross-finances less profitable uses in an other area.

- And finally (and in view of the long period it takes to transform the 600 hectare site), it allows granting farmers an extended lease to continue agricultural production on their former land as a compensation for the lower purchase price they received.

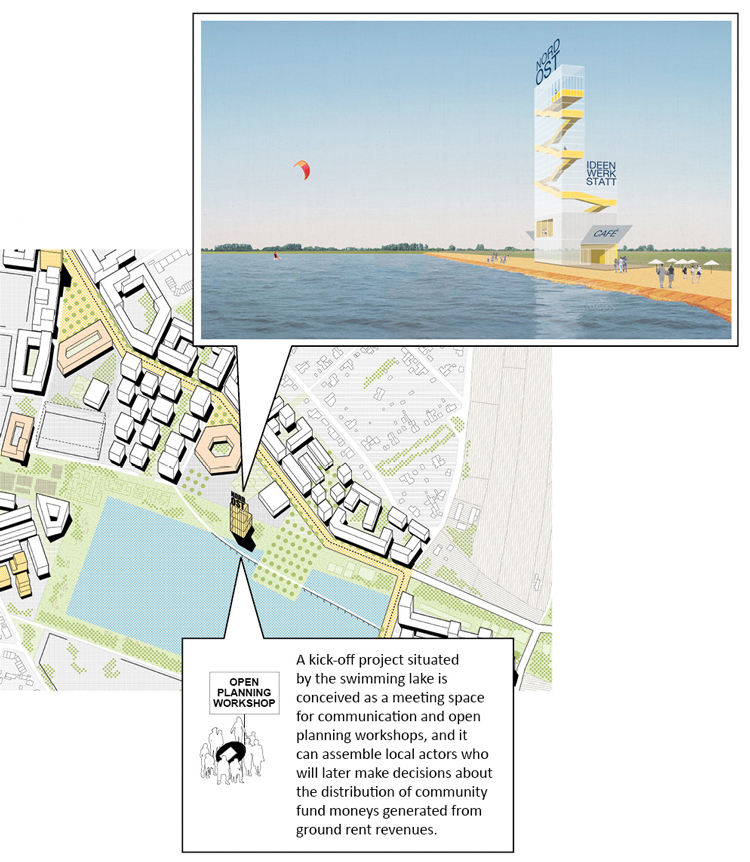

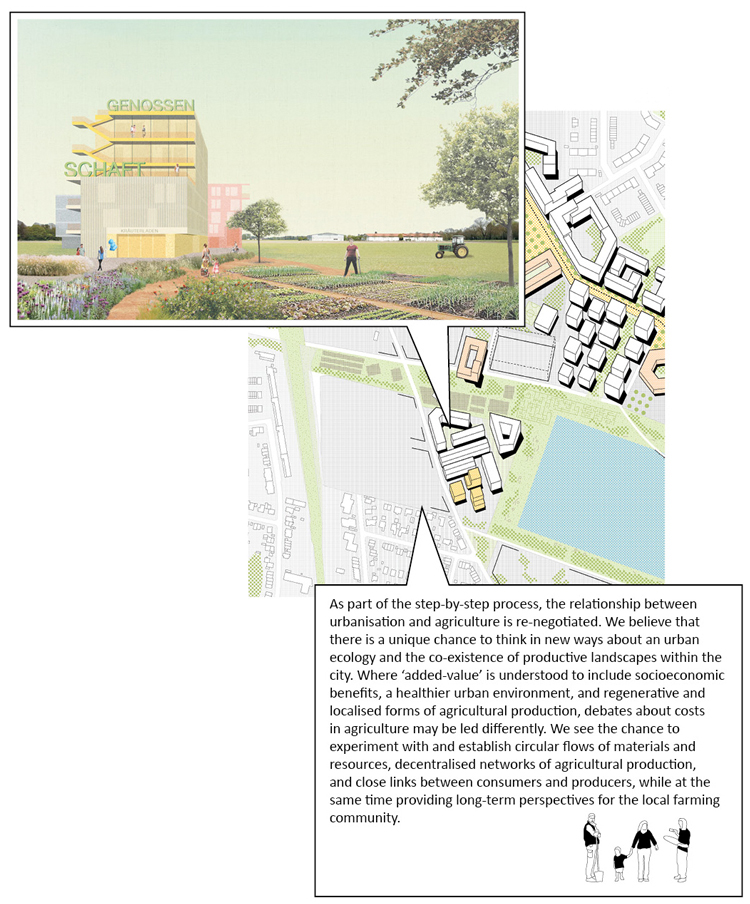

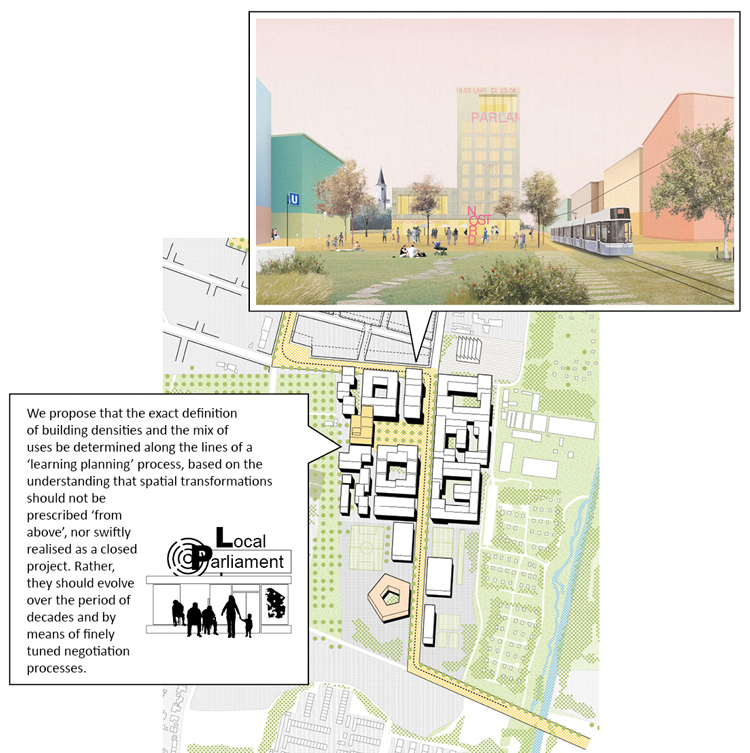

These aspects illustrate that we consider varying time horizons as well as questions of participation to be essential parts in the practical application of the proposed instruments. Therefore, we have limited the number of pre-defined development parameters in the proposed spatial framework to the following few: a network of open spaces including a large public swimming lake defines the basic layout for the accommodation of around 66,000 inhabitants over the following decades. However, the exact definition of building densities and the mix of uses can only be determined along the lines of a ‘learning process’. Spatial transformations should be neither prescribed ‘from above’, nor swiftly realised as a closed project. Rather, they should evolve over a period of decades and by means of finely tuned negotiation processes. A kick-off project situated by the swimming lake is conceived as a meeting space for communication and open planning workshops, and it can assemble local actors who will later make decisions about the distribution of community funds generated from ground rent revenues. We believe this is a promising way towards a truly co-produced ‘city of the many’ [Image 8-11].

Image 7. With the proposed leasehold system the surplus value of urban land, which is the collective product of the urban population as a whole, is effectively and permanently redistributed to the urban polity. Source: Authors.

Image 8. Image from the open process towards the ‘CITY OF THE MANY’. Source: Authors.

Image 9. Image from the open process towards the ‘CITY OF THE MANY’. Source: Authors.

Image 10. Image from the open process towards the ‘CITY OF THE MANY’. Source: Authors.

Image 11. Image from the open process towards the ‘CITY OF THE MANY’. Source: Authors.

+

The Team Stadt der Vielen includes: Andy Westner, Christian Zöhrer, Europa Frohwein, Imke Mumm, Julia Preschern, Julian Numberger, Max Ott, Norbert Kling, Peter Kühn, Thomas Hess, and Werner Schührer. Our project was developed with the support of Nick Förster, Massimo Falconi, Sonja Schneider, Martin Mitterhofer, Sophie Schwarz, Omar Mekati, and Eva Hermann.

Max Ott studied architecture and has worked as an architect. From 2011–2016 he was a research associate at the Chair of Urban Design and Regional Planning at the Technical University of Munich and since 2017 he has been a guest lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences Munich. Max is an associate member of the interdisciplinary research group Urban Ethics, funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Currently, he is working on his doctoral thesis and as a freelancer for the Berlin housing cooperative urban coop.

Norbert Kling is an architect and urbanist. He is currently teaching design and theory at the Technical University of Munich, where he received a Dr.-Ing. in Architecture. His research interests include conditions of asymmetric urban change and alternative spatial practices, as well as questions of concept formation, method and process in the spatial disciplines. His new book “The Redundant City. A Multi-site Enquiry into Urban Narratives of Conflict and Change” will be published shortly. He is a partner at zectorarchitects London/Munich.

Christian Zöhrer is an architect and urban designer. He studied architecture in Munich and Zurich and from 2014-2019 he was a research associate at the Chair of Urban Design and Regional Planning at the Technical University of Munich. Christian has given workshops at the TU Munich, Munich University MUAS, the University of Belgrade and is co-editor of the book „Porous City – from metaphor to urban agenda“. He is a partner at Westner Schührer Zöhrer Architects and Urban Planners based in Munich.

Volume 3, no. 3 Autumn 2020