Four pocket parks: Towards landed commons

– Guillaume Vanneste and Nicolas Willemet

A urban public policy

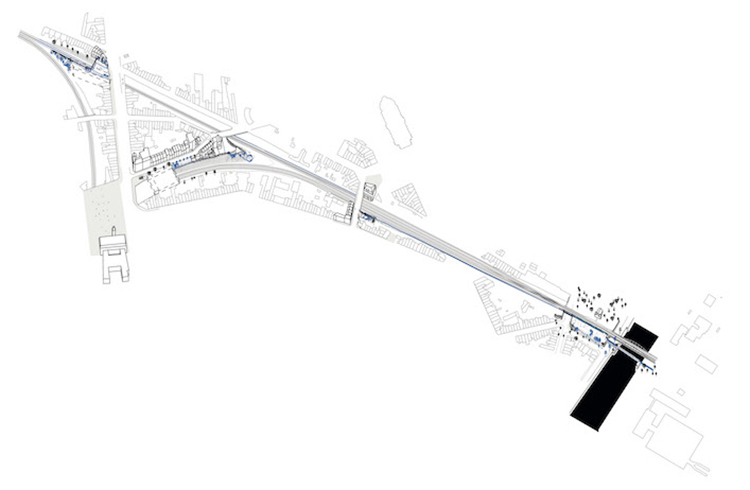

The project of four pocket parks is being carried out in the framework of the sustainable neighbourhood contracts (contrat de quartier durable), an urban renewal policy at regional scale in Brussels, in which regional funds are subsiding communal urban refurbishment1. In a specific communal perimeter – a neighbourhood – a group of operations such as public space renovation, public housing development and public equipment construction are being developed within a four-year program. Since the launch of this policy in 1993, about 80 contracts have been successful. Being part of one of these local contracts (Bockstael), the four new pocket parks are located along the L50 railway lines, on leftover and residual spaces. Meant to complete a set of larger operations, the four plots’ smaller sizes and undefined status locate them at the edge of traditional design and allow for an experimental process. At the intersection of architecture, landscape, urbanism and sociology, the project is carried out for the city of Brussels by a multi-disciplinary team of designers2.

A frame for experimentation

Brussels, as a growing metropolis, is undergoing important transformation processes regarding estate developments, mobility infrastructure and open space revalorisation3. After decades of disinvestment in central popular areas, paths are opening up for building up a mesh of connected open public spaces, able to sustain both ecological and social values through larger spatial structures embedded within both local and metropolitan scales4. In parallel, Brussels is the fertile ground for heteroclite bottom-up movements, endorsing spatial reclaim, upcycling politics and often embodied in or in search for a specific urban anchorage5. The following description aims at reflecting from the starting point of an experimental design trajectory to envision how common land is being defined within the mentioned framework and dynamics and it fits its own context.

Public spaces as a resource in the city

The contemporary city presents a relatively heterogeneous fabric where various patterns, infrastructures and facilities overlap. Cities leave at their fringes a series of open, abandoned spaces, motorway embankments, railways, old industries. They are generating what has been coined as a drosscape6 or a Tiers-Paysage7, a backlands context generally made of inaccessible, unclaimed or unused lands. These pieces of urban-nature, whose artificiality does not dismiss their ecological value8, both raise questions and bear potentialities within the undefined nature of their use and management. The ever-increasing urban density makes us reconsider these leftovers as a social resource and as new places for open space projects. Their reappropriation is today an opportunity to rethink the forms of public spaces for the city of tomorrow.

Common land

The context of general crisis today is giving rise to a great deal of desire in civil society, which is calling into question the notions of ownership, service and the value of human work and transition. Commons9, shared logics, co-construction, circular economy, repair-cafes, neighbourhood compost, places of experimentation, are all initiatives that participate in the transformation of public spaces. The Pocket Parks project is intended to become a ground for these initiatives, as broadly as possible, and to value participation as a basis and tool for the project. Reversely, the communality of the ground and its availability for potential appropriation lies at the root of the possible agency of the actors. Tracts of land waiting to be reclaimed might be a condition for people to gather around a collective project that generates cohesion. These future new places will depend unconditionally on this local involvement. More generally, a landscape project is a long term undertaking, and its sustainability is linked to its management and appropriation by the inhabitants. The Pocket Parks could then become these new commons.

Image 1. Four Pocket Parks in Brussels, location map. Source: Orthophotoplan, IGN 2018.

Image 2. Along the L50 railway line, axonometric view. Source: vvv architecture urbanism.

The four sites

In this sense, the project of the Pocket Parks becomes a research tool and raises several open questions on the status of these tracts of land in the city. How can we turn these places into new spatial and social resources? Who are the citizens involved and how does the land availability support new agency of actors around a place? How should such places be designed? Should they be assigned specific functions or left vacant and available for multiple uses? How can they be appropriated and identified as new places for the neighbourhood? How is land property a concept to question in light of these new urban arrangements?

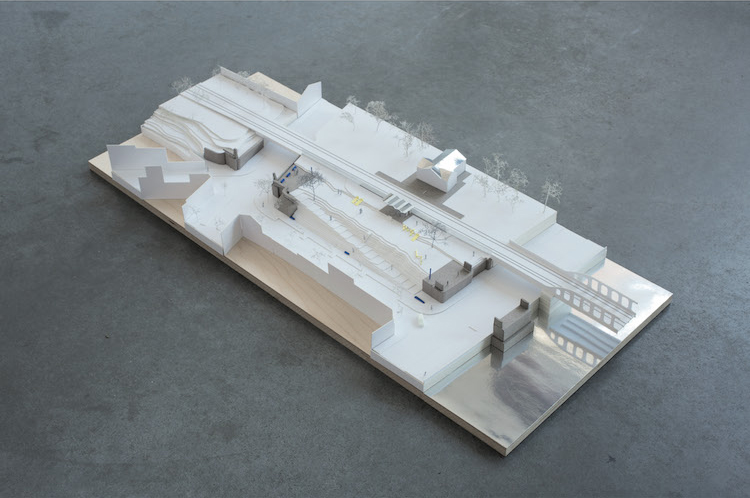

To unravel these questions, four visions are proposed on each park, operating both as small neighbourhood-scale facilities and more largely as inscribed in a metropolitan continuity able to make sense within the city’s landscape and geography. La Terrasse, an urban belvedere, a future threshold for new housing and bike amenities (bike repair store and parking); le Vallon, a place immersed in a dense vegetal talus along the railway infrastructure offering far-reaching perspectives over an urban panorama; le Jardin-Station, the experimental vegetable garden of the district; and finally la Halte Royale, the former royal station facing the canal and the district’s gateway to the city. They were the starting point of the discussion between the designers and the inhabitants, and the whole set of actors involved in the realisation of the project.

Image 3. View of the pocket park La Terrasse. Source: vvv/bloc/Pauline Cabrit/Pauline Varloteaux.

Image 4. View of the pocket park Le Vallon. Source: vvv/bloc/Pauline Cabrit/Pauline Varloteaux.

Image 5. View of the pocket park Le Jardin Station. Source: vvv/bloc/Pauline Cabrit/Pauline Varloteaux.

Image 6. View of the pocket park La Halte. Source: vvv/bloc/Pauline Cabrit/Pauline Varloteaux.

Image 7. Model of the pocket park la Halte. Source: vvv architecture urbanism.

Image 8. Model of the pocket park la Halte. Source: vvv architecture urbanism.

Approaches with actors for envisioning futures

Just like stepping stones, the Pocket Parks project aims at local, territorial and social connections. The sites themselves are both the conditions in which a social and urban project could occur and the pretext for creating such a common project. In that sense, actors, citizens, associations, designers and decision-makers are conceived as dynamic elements who interact with and bring elements to the development of the project. The actors mobilized on the project are numerous and complex, being institutional actors on the one hand and an association from the civic society on the other: Infrabel, SNCB, Citydev (a public housing developer), communal services (management of the urban contract and maintenance of the public spaces) as well as neighbourhood associations (BRAVO, …) and neighbourhood communities. In the search for a spatial definition for the places, and according to each site, some approaches were preliminarily sketched out to open discussion with the set of actors.

These approaches have been conceptualised according to each site’s possibilities and potentialities. Different strategies have been implemented, with varying but realistic levels of involvement and participation, ranging from perception, maintenance, programming or redesign. Here are some of the actions taken during the process: enhancing the site’s visibility through spatial or artistic installations, public presentations to an assembly of the local population, collective walking, occupation of the site with sheep–showing how they would mow the lawn over a period of time, the building of models during workshops or on-site supervised participatory construction work. A broad diversity of actions and a repeated and frequent presence on site was a key element in successfully gathering actors and instigating connections between them.

From the four sites, the Jardin-Station, the smallest but most accessible, served as a base camp for the gatherings and activities around the project of the four sites. After the de-contamination was carried out by a contractor, a group of associates and neighbours started to realise this pocket park (with the help of the design team) through the construction of: planting beds, a cistern for rainwater harvesting, small seats and a screen for cinema projection. Once opened, the site has continued to be a place for those collectivities to meet and exchange. The three other sites are technically more complex and will require a complete intervention of a construction company. Nevertheless, they followed the same path of dialogue during conception and will be reopened for occupation and uses once delivered.

Image 9. Open air cinema in the pocket park Le Jardin Station with associations. Source: vvv/bloc/Pauline Cabrit/Pauline Varloteaux.

Image 10. Co-construction of the pocket park Le Jardin Station with neighbours. Source: vvv/bloc/Pauline Cabrit/Pauline Varloteaux.

Image 11. Opening of the pocket park Le Jardin Station. Source: vvv/bloc/Pauline Cabrit/Pauline Varloteaux.

Image 12. Opening of the pocket park le Halte with the sheep of Maximilen Farm for grazing. Source: vvv/bloc/Pauline Cabrit/Pauline Varloteaux.

Learning from

A leitmotiv during the participatory processes has been to concentrate as much as possible on what was “already there”, either in terms of human resources, material conditions or even simply regarding what could be called the “spirit of the place” and what to keep or to reuse. Moreover, it allowed conclusions to be drawn on what was learned and gave possible answers to the questions asked earlier. Land availability was a prerequisite for uses, practices and social network to be developed. If the mobilization around the site can be considered as an introductory part, the conditions for long-term existence of stakeholder coalitions are not ensured by the mere existence of the plot. The risk is high that when the designers or the actors involved leave, this transmission of the knowledge built during the self-construction workshops and planting days, for instance, will be lost or weakened. Occupation of the land, as a group, leads to the building up of shared knowledge and conviviality, implying that the group should find a way to transmit this knowledge to enable the land to remain a resource. Finally, working with this thrifty and economical attitude was a design position that left room for the construction of a specific agency. Inasmuch as the construction is still ongoing, the path to finalising the projects will be long, but until now the project has become a place where actors and approaches have gathered, collapsed or coevolved towards the realization and experimentation of a common land.

Image 13. Photography of the construction site. Source: Séverin Malaud, 2020.

Image 14. Photography of the construction site. Source: Séverin Malaud, 2020.

Notes

1. See: Berger, M. (2019). Le Temps d’une Politique. Chronique des Contrats de quartier bruxellois;

Bruxelles Environnement (2020). Les maillages. [online] Available at: https://environnement.brussels/thematiques/espaces-verts-et-biodiversite/action-de-la-region/les-maillages/ [Accessed 02 Nov. 2020].;

Degros, A., & Decleene, M. (2014). Bruxelles, à la [re]conquête de ses espaces. L’espace public dans les contrats de quartiers durables. Bruxelles: Service public régional de Bruxelles.

2. The complete team is constitued of vvv architecture urbanism (Guillaume Vanneste, Nicolas Willemet, ir. arch. and researchers), Bloc Paysage (Louise Lefebvre, landscape architect), Pauline Cabrit (landscape architect and urbanist), Pauline Varloteaux (architect), Margaux Vigne (sociologist and architect).

3. Vandermotten, C. (2014). Bruxelles, une lecture de la ville. De L’Europe des marchands à la capitale de l’Europe. Bruxelles: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

4. See: Bruxelles Environnement (2020). Les maillages.;

Devoldere, S. ed. (2016). Metropolitan Landscapes. Espace ouvert, base de développement urbain. Brussels: Maître architecte flamand.

5. Mercier, J., & Mercier, C. (2018). Paysages citoyens à Bruxelles : 50 lieux où la nature et l’humanité ont repris leurs droits. Bruxelles: Racine.

6. Berger, A. (2007). Drosscape: Wasting land in Urban America. New-York: Princeton Architectural Press.

7. Clément, G. (2003). Le Manifeste du Tiers-Paysage. Editions Sujet/Objet.

8. Gugger, H., & Macaes e Costa, B. (2014). Urban-Nature: The Ecology Of Planetary Artifice. San Rocco, Ecology (10), pp. 32-40.

9. Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

+

The work presented in this article has been produced as part of a project developped with a team constitued of vvv architecture urbanism (Guillaume Vanneste, Nicolas Willemet, ir. arch. and researchers), Bloc Paysage (Louise Lefebvre, landscape architect), Pauline Cabrit (landscape architect and urbanist), Pauline Varloteaux (architect), Margaux Vigne (sociologist and architect).

Guillaume Vanneste is an architectural engineer, researcher and teacher at the Faculty of Architecture, Architectural Engineering and Urbanism in the Université Catholique de Louvain (LOCI-UCLouvain). He is a founding partner of vvv architecture urbanism. He teaches a design studio at masters level and is pursuing doctoral research on the production of contemporary city territory in Belgium.

Nicolas Willemet is an architectural engineer and took part in teaching and academic research projects at the Faculty of Architecture, Architectural Engineering and Urbanism in the Université Catholique de Louvain (LOCI-UCLouvain). He is a founding partner of vvv architecture urbanism. His experience was built up during his career in Switzerland and Belgium in renowned architecture offices such as Localarchitecture and L’Escaut.

Within vvv, they develop projects of architectural projects, public spaces and urbanism in Brussels and in Belgium. In particular, vvv has won a number of public projects such as the Pocket Parks along a former railway, renovation of Place Marie Janson in Saint-Gilles and the masterplan for the Peterbos Housing Park in Anderlecht. The office approach seeks to conceive spatial structures with particular care for and interest in the social and material context, while always maintaining a critical research perspective.

Volume 3, no. 3 Autumn 2020