The community land trust, Stadtbodenstiftung, in Berlin on turning land into commons

with Andre Sacharow

Stemming from a longstanding tradition of civil rights activism and campaigning, the community land trust movement aims at implementing models of common landownership. Drawing on community organisation and long-term landownership for social purposes, community land trusts try to bring back common ownership as a legal category in land management. Andre Sacharow is the incumbent co-director of the Stadtbodenstiftung – a community land trust in Berlin. With one foot in rent activism, and one foot in learning a new form of co-production between civil society and city administration, Andre currently devotes most of his time to the Stadtbodenstiftung. Whilst pursuing interdisciplinary studies in London with a focus on the city, he participated in the establishment of a community land trust there. Based in Berlin since 2017, he has been involved in the organisation of the Experimentdays 2018, and with the non-profit association id22 as a board member.

1. What is a community land trust understood as globally, and what does it do?

Community land trusts (CLTs) develop independently and in their local contexts, so their activity is very diverse. In Berlin we are building the Stadtbodenstiftung [literal translation City Land Foundation] as a local organisation that is inspired by the CLT principles but adapted to local needs. The CLT movement can look quite differently in different cities, it must adapt to local problems and to what residents and neighbourhoods need. I think the best way to describe what CLTs do is to look at the three namesake principles: community, land, and trust. Firstly, CLTs are about community-organising and community-led development on community-owned land. Secondly, the movement tackles land ownership, the securance of long-term land ownership for social purposes. Thirdly, trust is understood as trusteeship. CLTs act as trustees for the land they hold and make sure it is used by and for people or communities who are currently less able to access land. This includes people with lower incomes, social and cultural institutions, or generally disenfranchised neighbourhoods.

2. How would you explain the importance of CLTs to someone who has never heard of them? How has the movement developed?

The first CLTs were created in the wake of the civil rights movement in the USA and aimed at securing access to land for black communities. Their approach of ‘commoning’ the land through common ownership arrangements was inspired by a long tradition of movements in India, the UK, Israel, and many other places. In a sense common ownership of land can be called the standard that was present until only a couple of centuries ago, when private ownership of land started to take hold globally.

At its core, the CLT movement aims to bring back this common ownership category into our legal system, which is currently geared towards private land ownership. It was developed during the civil rights movement by African Americans who viewed land ownership as the key to emancipation. To achieve equality, they demanded access to land, and they were themselves inspired by various movements, such as the Kibbutz movement in Israel, and the Garden Cities movement in England.

So, the CLT model was born in the USA, to then grow, move and adapt to many different circumstances. There are now more than 200 CLTs across the US. In the UK, too, the CLT model has a big following. Today there is a great example in Puerto Rico, with a 10,000 people-strong informal settlement turning into a CLT. There are also pilot projects in Europe, in Brussels for example, and an adaptation of the model being developed in France. Here in Berlin, we are building the first community land trust in the German legal context.

3. How did you first become involved with CLTs?

When I was studying in London, I experienced the urgency of the housing question not only because of my personal struggle to find a decent home, but even more through what was happening in my neighbourhood. Without any tenant protection people were at the mercy of the market with entire families living in a single room and rental agreements lasting no more than a year. Furthermore, social housing was destroyed at a faster pace than it was built due to estate regeneration and the ‘right to buy’ legislation.

Stirred by this situation, I got to know a neighbourhood initiative in my area, which was proposing a CLT locally, on the site of a former hospital. This site was supposed to be privatised, but the community opposed this plan by envisioning a way to keep it in common ownership and realize a community-led development of 800 affordable homes on that plot of land. When I moved to Berlin, because of my involvement with the CLT in London, I quickly got introduced to groups and initiatives working on community-led development in Berlin. Furthermore, I moved into a house in Germany, which was put up for sale shortly after. Together with all the neighbours we organised and developed a model to take it off the market forever, buying it together with a foundation similar to the CLT model, and establishing it as self-governed, low-cost housing for people who need it.

4. When speaking to people who are not necessarily already involved or interested in alternative housing models or non-speculative housing models, what do you think are the most persuasive aspects of the community land trust model?

What I find most intriguing about the CLT model is how versatile it is. There are so many aspects to it, depending on what your perspective is you will find an aspect that resonates with you and your values. The one defining aspect is the idea of democratisation of urban development. For instance, this is particularly important if you are concerned about how commercial spaces are used in your neighbourhood–what kind of services they offer and how accessible they are. Top-down gentrification enacted by real estate companies cause the loss of crucial local neighbourhood functions. By getting hold of the land through the CLT model, city dwellers can make sure that local initiatives do not get gentrified out due to spiking rental costs. From another perspective, the focus of CLTs can be placed on the idea of common ownership and on the vision of the city as a commons.

5. How is establishing a CLT in Germany different or similar from doing it in other countries and what is the relationship between the Berlin CLT and the global CLT Network? Is there something particularly specific to Berlin, when trying to implement CLTs?

Yes, there is several things that distinguish Berlin from other contexts. Firstly, Berlin is a tenant city, with over 90% of residents renting. Thus, the focus of the CLT model must be on securing tenant-occupied housing. Secondly, Berlin has a very rich history of housing struggles and neighbourhood initiatives, so the CLT participates in and contributes to a larger political movement. Thirdly, Berlin already hosts many different forms of non-speculative housing, for instance cooperatives, the Miethäuser Syndikat, communes, and state-owned housing companies.

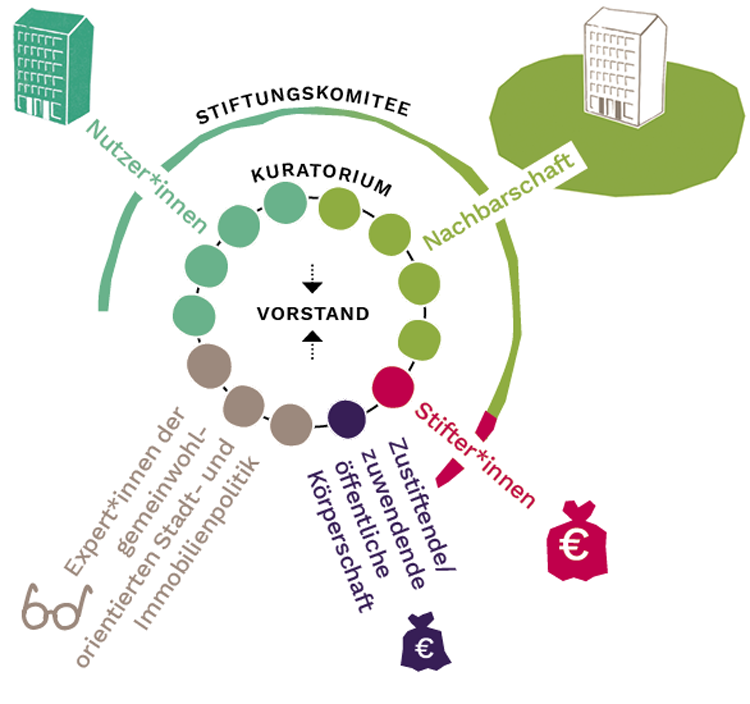

We hope that the Stadtbodenstiftung – Berlin’s very own CLT – can act as a platform where non-speculative initiatives cooperate and come together by realizing projects on land owned by the CLT. This can strengthen solidarity amongst projects and initiatives. In this way, the community land trust would be an enabler for further cooperation, making a different city possible.

6. Do you think there’s factors that make it easier or more difficult to do this in Germany as opposed to other European countries, for example, or other countries that you know of that are working with this model?

I do not think so. I think inventing a new structure and making it happen will always be hard work, regardless of where you are. Surely, the process of creating the first CLT is harder now in Berlin as opposed to countries that already have the legal setup as well as successful examples. However, in Germany we can also find functional examples that are close to the CLT model. We have learned a lot from these projects and replicated and adopted their structures and ways of working.

7. What do you think have been the main challenges so far for the community land trust in Berlin?

Apart from the very process of setting up the Stadtbodenstiftung as a legally recognized foundation, I think there are several big challenges which we are working on. One challenge is to mobilise the necessary finances to make this happen. Until you are a legally recognised organisation you cannot access many types of funding. At the same time, becoming a foundation is a huge challenge without having secured funding. Furthermore, it is very difficult to develop a first project without yet being a legally recognised organisation. This moment is a challenge for us, but we are gradually building our credibility and making further steps in raising funds.

8. In the EU, the rent freeze introduced by the Berlin Municipality has been considered as ground-breaking. A main argument against though, it is that new construction would come to a halt and that maintenance would stop as there is no incentive for owners. How would CLTs operate differently? Does this halt give CLTs a competitive advantage? What is your view on the freeze?

The Mietendeckel (rent freeze) is extremely important for many people who are suffering from spiking rents and who are threatened with being displaced from their homes. I cannot stress enough how crucial it is for the vast majority of renters and tenants in Berlin right now. However, it was not developed as a long-term solution. We need to find solutions that last for longer than five years, solutions that scale and create different dynamics of how cities could work.

stadtbodenstiftung.de

Volume 3, no. 3 Autumn 2020