Billboard Space in Egypt: reproducing nature and dominating spaces of representation

– Mohamad Abotera and Safa Ashoub

In the last couple of decades, billboards have dominated Cairo’s skylines with a substantial and noticeable increase after 2011. This has come with the developments in the marketing field and the technological advancements that allowed for the usage of different types of media to place advertisements in different places and in different formats. Billboards advertise countless products, but it is easy to notice that real estate advertisements have a significant share, especially when it comes to advertising new gated communities.

Taking a closer look at such real estate billboards, one can’t help but notice that they all present some sort of a promise. If we analyse their general visual and substantial characteristics, we can find some recurrences. There are clearly many messages of promises being delivered through such advertisements and they mainly stress on the promise of self-actualisation and satisfaction, based on an unmissable attempt to promote exclusivity, even if it is essentially a form of social and urban segregation1.

In an attempt to analyse these promises, Farha Ghannam points to three main focal points that they attempt to deliver on; the body, children and education, and mobility (Ghannam, 2014). There is more to this concerning the message though and, in our case, the existence of billboard structures in the urban environment as such. Almost all billboards exhibit elements of nature 2 in them. They promote a lifestyle that enjoys greenery and spaciousness in a clear – sometimes explicitly presented – contrast with the grey congested city.

The elements often used in these messages include trees, grass fields, golf courses, the sky, and water features – as opposed to showing images of the built environment and the detailed features of the available units. In addition, space in its abstract sense is not directly promised, but it rather seeps in subtly with the promise of spaciousness and the presented ‘natural’ environment. The presence of elements of nature is so prominent that in some cases they are the sole advertised feature.

There is a twofold significance here – we argue – the physical and the mental. While billboards exhibit images of architecture and ‘nature’ as a promise, their physical presence ironically obscures existing architecture and elements of nature, thus contributing further to their scarcity and to the crowdedness of the city. That is, in other words, covering the ‘real’ elements with the ‘promise’ of similar ones.

On the other hand, while almost all advertised developments are built in the desert, the images displayed are quite distant from the aridness of the desert. Moreover, the exhibited elements of nature are quite alien to Egyptian terrains in many cases. Historically in Egypt, the Nile rhythm regulated both nature and urbanism in the valley (Azzam, O., 1960). There has been a dichotomy of the valley and the desert; a binary of life and death, inside and outside, state and statelessness (Hemdan, G., 2001). However, urban projects in the desert and the way they are advertised present a novel vision for the valley-space 3 and the desert-space. The valley space is the fertile land created by the Nile River, running through Egypt and dividing it into two almost asymmetrical halves. Today, they are referred to as the Western and Eastern Deserts with the Nile valley in the middle, where most of the cities are built and developed4.

With that in mind, we are going to look at the effect of real estate billboards on the city space and on the mental image of the desert, focusing on nature as a field of investigation. Our domain of search is based on the city of Cairo, including its extensions in the desert.

Advertisements and billboards are a predictable product of a real estate free market, nevertheless we have reasons to believe they are also related to a State Mode of Production through their spaces of representation, following Lefebvre’s theory on the production of space and representation (Lefebvre, H., 1978; 1980). We propose that either the image of the valley-space is expanding, or that the dichotomy is inverted so that the desert-space starts to represent order, liveability and statehood, as opposed to the stateless informality of the congested valley. Moreover, we question the state’s attempts towards producing this new space of dominance as an expansion of state space. In this paper, we are attempting to understand issues of state hegemony, its mode of production of space and dominance over spaces of representation through the instrumentalisation of urban planning and the images it promotes.

1. The recent densification of advertising billboards, NA road, Mohamad Abotera 2016

SECTION 1

Billboards and scarcities in the urban environment

As a marketing strategy, it is common to use allegedly scarce qualities to attract potential customers, namely by associating such qualities with the advertised commodity as promises. This is true for the marketing messages being communicated on billboards as much as other methods of advertisement in Egypt. We are consequently approaching the subject of this paper through the lens of scarcity.

In a previous study, Petra Kuppinger lists some of the qualities that gated communities promise, which are: bountiful greenery, healthy living environments, high quality lifestyles, comfort, convenience, community services, and peace and quiet (Kuppinger, P., 2004). Or, as Khaled Adham names them: convenience, spectacle, and total living experience, then annexing: clean, organised, human-scaled and green environments, in his study on new spaces of capital in Cairo. Adham also sees that these are qualities that Cairo no longer has (Adham, K., 2005). We notice that greenery is among the promised urban qualities both researchers include. We can hence claim that greenery is – at least commonly perceived as – scarce in the urban environment of Cairo, which is the focus of our observation and fieldwork.

2. An example of the promises on the billboards and their connotations of self-actualisation and class, Mohamad Abotera 2016

Space and ‘green nature’ scarcity in Egypt

Before we continue with billboards, it is noteworthy to point at the type and extent of scarcity of ‘green nature’ in Egypt. Henri Lefebvre refers to the classical elements of nature in his theory as: air, water and light (Lefebvre, H., 1970). In Egypt, the scarcity of these elements is not a novelty, especially water. Water has always been limited and Egypt has always relied almost completely on the River Nile as the main source of water and thus became closely linked with irrigable and inhabitable land (Hemdan, G., 2001). Green nature associated with water resources have been then the main scarcity.

Likewise, urban planning always followed the patterns of water and green nature as the prime differentiators that also reflected the prevailing socio-political structure along different eras (ibid). Although the irrigable area has multiplied from 2 million feddans5 in the early 1800’s to 8 million now due to continuous land reclamation and agricultural projects (Sims, D., 2015), green nature remains scarce since the population rose from 2 million to over 90 million over the same period of time.

3. The scarce irrigable and inhabitable land in Egypt, Google Maps 2016

The issue of scarcity is not just mathematical or quantitative, but also political and conceptual. In his article ‘Reflections on Political Space’, Henri Lefebvre states that nature is political since it is embedded in direct and indirect strategies. He also claims that to the extent nature is mastered and dominated, it is annihilated so that it becomes the new scarcity of the world (Lefebvre, H., 1970). When applying this theory to Egypt, we see that, despite that water scarcity is not new, the pressure on water resources is directly proportional to the ability to manage the resource and to control the Nile, which has been largely tamed with the building of the Aswan High Dam in 1970 (Hemdan, G., 2001).

Finally, Lefebvre predicts that a time will come “…when we will have to recreate nature” and space as a basic condition for production (Lefebvre, H., 1970). We wouldn’t say that the advertised new residential gated communities are a reproduction of nature – in fact they aren’t natural at all as we will show below – however, there is a clear persistence on creating sanctuaries of abundant greenery in the middle of the dry desert. The re-creation of nature in this case seems more associated with consumerism than with productivity.

Greenery on billboards

When greenery is such a scarce and desirable urban feature, it is therefore expected to be represented on billboards; literally, visually or symbolically. To investigate this, we surveyed an 8.5 km main road in Cairo, studying the positioning of billboards with regards to urban space and their messages 6. We found that the presence of elements of green nature was prominent in most marketing campaigns. Out of 29 real estate billboards, only 6 had no elements of nature to sell with, while 23 had one or more elements presented as unique selling propositions.

Signs of greenery appeared in several forms: in the imagery, in the textual message and in many cases in the name of the project (e.g.: park, trees, lake, green, a flower name, golf …etc.). The strength of the signs’ presence was in some cases subtle, where green elements appeared only as the background of architectural renders, while in some other cases, a sign of green nature was the sole message on the billboard.

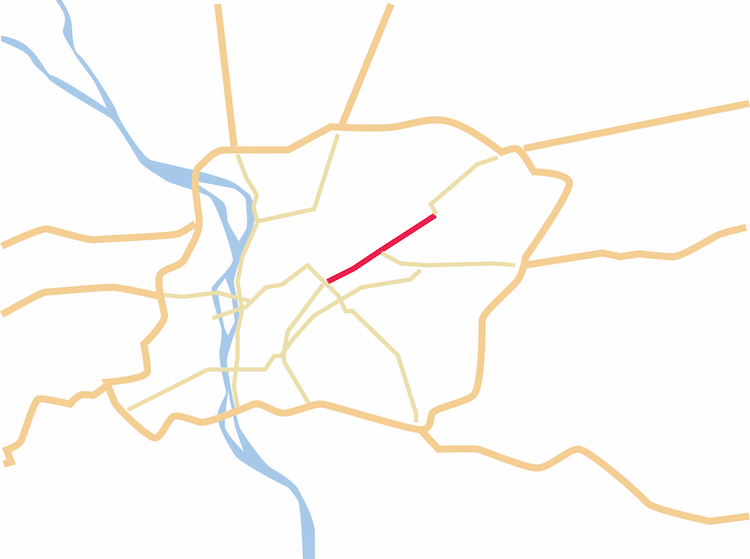

4. The location of the surveyed road (Orouba Rd.) in east Cairo.

5. Two examples of the advertised green nature in the new gated communities, Mohamad Abotera 2016

The contribution to scarcity

Despite the attempts of new gated community projects to provide greater access to green spaces, they seldom improve the situation. It can even be argued that their attempts reinforce the scarcity they are allegedly countering on the national level, thus making conditions worse for residents of older Cairo quarters. This is not only true when it comes to the physical space occupied by the communities themselves, but also due to the positioning of the billboards that advertise them as we are going to show.

Evidently, residents of the advertised gated communities enjoy much more greenery than people who live in other quarters of Cairo. However, as a general theory, the movement of residents from the city to suburban gated communities has a negative impact on existing public spaces and services, including green spaces (Kuppinger, P., 2004). More specifically to Cairo, the share of green areas per capita varies greatly per quarter while remaining little for all in comparison to the global standards. The share in the old city quarters does not reach 0.1 sqm/capita in many cases whereas the share in Heliopolis as an example of early 20th century quarters jumps up to 7 sqm/capita (Tadamun, 2014).

What is worth regarding here is that residents of quarters that enjoy a relatively higher share of green space like Heliopolis already enjoy higher economic status and hence are the marketing target audience of the advertised gated communities. This is to say that people who can afford to enjoy greenery in a newly established gated community already have this relative privilege where they live, while the majority who suffer more scarcity will remain underprivileged.

Since the 1970’s, the Egyptian State has adopted a strategy of building new cities out in the desert around Cairo (Kingsley, P., 2015). In an attempt to solve its problems in their planning and building regulations, a minimum green space share per capita was set. Most gated communities lie in those cities along with governmentally planned residential areas. Despite the fact that residents of social housing projects in these cities enjoy a higher share of public space than older Cairo quarters – where they were mostly relocated from – they are still greatly underprivileged when compared to residents of gated communities. To prove this, we undertook a field survey 7 in New Cairo 8 as an example of newly constructed satellite cities. The survey measured the distribution of green spaces in relation to the economic status of the residents 9.

Privileging was evident when it came to the provision of green spaces in New Cairo, where the ratio of greenery to total space in residential areas is slightly above 50%, at the rate of 55, 54, and 50 for gated communities, private houses and social housing respectively. However, the big variation in population density bids the share per capita grossly unequal. While gated community residents have a share of 216 m2 of greenery per capita, social housing residents’ share is only 26 m2 in our sample areas. Accessibility to green areas is 744% higher for people living in the advertised gated communities, compared to social housing residents. The uneven distribution is even graver when we consider that only a small fraction of New Cairo is planned for social housing while the vast majority is for private houses and advertised gated communities that are only accessible for a narrow segment of the population.

Geographically, most new developments exist in the desert, whereas the interest in recreating green nature consumes much of the already scarce resource; namely water. Irrigation in the desert consumes far more water than in the valley, not to mention that some villages in rural Egypt are already suffering drought in their farms (Piper, K., 2012). The social crime – if we could say – of watering golf courses, comes at the expense of extending clean potable water to underserved areas existing within the city for decades now 10 (Tadamun, 2013).

On the other hand, billboards exhibiting green nature in their advertisements also have their share of reinforcing scarcity; the condition they capitalise on for selling. They often obscure or destroy the already exhausted elements of nature in the city. On the ground, they occupy space, crowding whatever little of it exists and, in some cases, at the expense of trees and green patches. From our field observation in the main road that we mentioned before, we found 4 cases out of 47 where billboards were built at the expense of trees or grass at the time of the survey, and ironically, all 4 used elements of nature to sell at the time.

6. Two examples of contribution of Billboards to the scarcity of urban nature. Their footprints occupy space and often built on green areas (left), and sometimes trees are cut to build new billboards (right), Mohamad Abotera 2016.

The impact also extends to the sky and the air. With no strict regulations, the density of billboards can become very high. In the same survey, we found that billboards can sometimes overshadow each other and it is very hard to look anywhere in the sky without seeing one. In some cases, billboards were so close to windows and balconies that people can literally touch them, not to mention how they obscure the sky and invade rooms with harsh neon lights. One wonders how far this can go before it is saturated. At the time we developed our case study, we counted 47 billboards over a stretch of 8.5 km at the rate of 5.5 per km, and we counted 4 newly built billboards, equivalent to an 8.5% increase in only two months.

SECTION 2

The struggle over mental dominance (confronting Seth)

-

“The fundamental event of the modern age is the conquest of the world as a picture.”

–Heidegger, M., 1977.

The classical desert image

The image of the desert has been long established in the Egyptian culture. It stands in a binary opposition to that of the valley constituting the mental image of the national territory for Egyptians, and even life. In ancient Egyptian mythology, there are two lands; Kemet (the black-fertile land); the valley close to the river where order exists and life is possible and Deshret (the red land); the desert, the land of beasts and ghosts ruled by Seth; the God of disorder and chaos (Sims, D., 2015). This mythology continued to shape the collective mental imagery of land for Egyptians until current times. Western travellers documented this, as Arthur Weigall noticed, the desert was the garden wall and the land boundary for Egyptians (Ibid).

7. The high contrast between the inhabitable valley and the arid desert, Aswan, Mohamad Abotera 2016

Even today, the hostile uninhabitable image of the desert is dominant among the majority of Egyptians. In an earlier research in one of the poor areas in Cairo, we found residents fiercely refusing relocation to new homes provided by the government in the desert, naming it ‘the mountain’, in reference to its harsh and unconquerable nature. This comes despite their current urban conditions being much worse and even dangerous at times (Zaazaa, A., Borham, A., Abotera, M., 2016). The case is different though among officials, scholars and the elite as we will show further on.

The desert as a space of invasion

Human activity in the Egyptian desert(s) has always been counter-connected to security. Fugitives have always sought a safe haven in the desert backdrop of main cities across the valley, away from the reach of authorities. In some cases, they even used the desert as a platform for planning and carrying on out their raids on the city. The (Egyptian) army on the other hand always operated in the desert, either using it as a location for its camps and outposts, or as a security buffer zone against raids and invasions, and the stronger the state was, the tighter it controlled the desert.

As a result, the image of the desert as a space of invasion prevailed for so long, to expand but mostly to eliminate internal and external threats. The notion of invasion prevailed however even after the modern Egyptian state was established in the late nineteenth century and the borders were formalised in the 1800’s. In modern times, with the advent of technology and the scarcity of space in the valley, the notion of desert land development became increasingly and more seriously discussed and planned, especially amongst officials and scholars, and even more after the 1952 regime change and Egypt’s full independence from British rule. Such developmental plans have been described and titled straightforwardly as ‘the invasion (or conquest) of the desert’ (Sims, D., 2015) (Hemdan, G., 2001) (Azzam, O., 1960).

The dream space of the rich and the state

As David Sims proves in his latest book titled ‘Egypt’s Desert Dreams’, published in 2015, the developmental goal of the ‘desert conquest’ is to achieve production, housing and growth since 1952 plans have failed gravely. However, the desert remains a dream space for statesmen appearing in every governmental plan until today (Sims, D., 2015). According to Timothy Mitchell, the development of the ‘new lands’ is the state’s usual solution to solve the problems of the ‘old lands’ (ibid).

Apart from the state, for some people, desert urbanisation is not a failure at all, or as Sims puts it, “In more recent years, however, the dream of desert development became a source of extraordinary wealth”. The main economic benefits didn’t come from collective wellbeing, employability, housing or productive life, but from land deals and contracting opportunities for a few well-connected entrepreneurs. Moreover, Sims also adds that the wealthy do not reject the desert. On the contrary; desert gated communities and private houses became a preferable housing option for the wealthy, where it became their ‘playfield’ as he describes (ibid).

The desert appeal for the elite did not start during the last wave of urbanisation since the 1990’s though. They have always been more willing to move to newly urbanised desert neighbourhoods around Cairo during the last century at least. However, an important qualitative difference can be noted between the early 20th century and current times concerning the mental image of the desert.

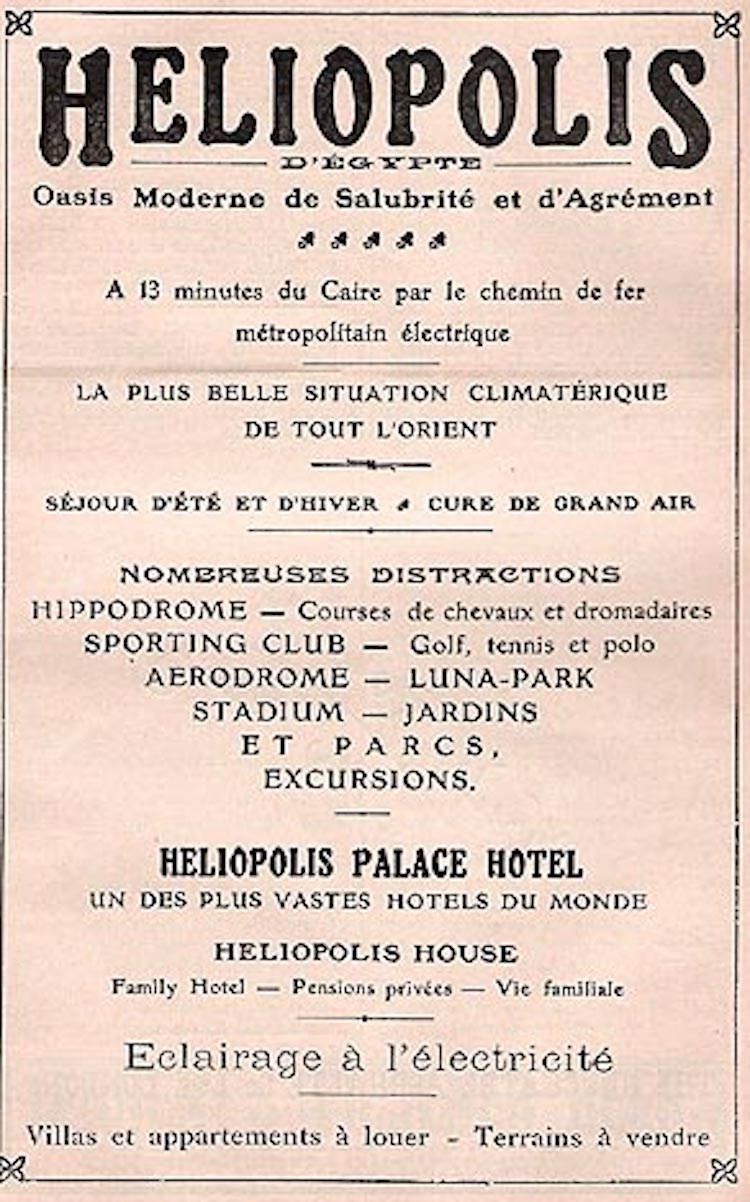

Analysing old advertisements of Heliopolis, a newly planned neighbourhood in the east of Cairo, established in 1905, we notice two points; first, it focused on leisure and modernity, highlighting aerodromes, hippodromes, sports clubs and tramlines, which may indicate the scarcities of the time as well; and second, the classical natural image of the desert was still visible. The official name of the project was Heliopolis Oasis, thus directly acknowledging the natural environment in which it was built. In his Doctoral Thesis on The Development of urban and rural housing in Egypt, Omar A. Azzam, notes that, “With the continuous upward trend of the Egyptian population, cultivated land becomes dearer and therefore new cities have to be extended into the desert. This is becoming easier with the extension of water supplies. The reclamation of desert land would create oasis-cities” (Azzam, O. 1960).

8. An old advertisement of Heliopolis Oasis project (constructed 1905), http://www.egy.com/landmarks/

SECTION 3

Imagery source: Elements from the Valley and from the West

A century later, the acknowledgment of nature ceased completely in advertisements of recent gated communities. As explained above, the majority of billboard advertisements forward green nature, defying both nature and traditional mental images. This can be, at a first thought, attributed to the notion of the desert invasion where the valley space is invading the desert space carrying its nature. On the homepage of the New Capital website (one of the new mega projects by the current regime), the slogan ‘a city formed by nature’ accompanies computer-generated images of sleek architecture and greenery. Needless to say, the city is built deep in the desert east of Cairo and nothing about it is natural (Kingsley, P., 2015).

9. Images from the New Capital website (http://thecapitalcairo.com/) 2016.

More interestingly, analysing billboard advertisements of gated communities shows that the type of green nature advertised is actually quite divorced from the green nature of the valley, not only of the desert. The green elements in the advertised images consist of open grass fields (often golf courses) and trees, all belonging to a temperate climate that only exists across the Mediterranean. It could be argued that the choice of elements of nature comes from the Nile valley (water and green nature) but the elements themselves and the image frames they are assembled in are probably European and North American.

On this, David Sims states that “[i]n fact, the main selling point of these projects seems to be that they create the illusion of being Europe-like enclaves ‘outside Egypt’ and are as divorced from their desert environments as possible.”. Every effort is made to obliterate any reminder of the surrounding desert (Sims, D., 2015). In one advertisement for ‘Uptown Cairo’, an image of Los Angeles is used as the main selling point with a slogan saying ‘Living Above It All’. Even in naming, one of the gated communities for example is explicitly named after Hyde Park of London. According to this thesis, the invasion is not purely carried out by the valley space but also by foreign spaces.

10. Hype Park gated community advertisement, Mohamad Abotera 2016

11. Uptown Cairo gated community advertisement on a background of Los Angeles cityscape, Mohamad Abotera 2014

Producing the imagery, the role of marketing agencies

How do such images of foreign nature find their way to advertisements? To answer this question, we interviewed two people; one working in an advertising agency and the other in the marketing department of a real estate development company. Both testimonies where identical on the process of image production. The developer (or client) only presents facts, target audiences and market differentiators (unique selling propositions), and passes them on to the marketing agency. The agency then creates marketing materials stressing on the message, with its slogans and images.

Images are rarely real, unless the project is almost finished. They are either computer renders or images from photo sessions or from internet stock libraries. The selection of images from the internet is based on finding photos that are close to the desired image of the proposed (promised) reality. Even in the case of renders, images are the production of the agency, not of the architect who designed the project. True nature is only regarded in the case of the beach or the mountains, but never the desert landscape that surrounds them. Agencies are quite aware they are selling lifestyles. Images signify the desired lifestyle and their source or truth is not as significant. They don’t advertise location, price, scenery, community or facility all in one ad. They send teasers and they phase their messages.

The desert as a space of inversion

Billboards simultaneously boost this invasion along with the projects themselves. While the state and the elites imaginatively invade the desert, billboards operate in the city to invade the mental image of the desert, imposing a different foreign nature, constructing utopias, and leading to the re-creation of the mental image of the national territory.

Yet, we find the analogy of invasion insufficient to explain the changes in the image of national territory. Invasion by definition implies the subordination of the invaded terrain, forcing it to remain inferior to the invader or at most an extension to it, carrying the same looks and values. From our observation, this is not entirely accurate of the case at hand. While the common desert image is changing positively, the image of the valley is being demoted, at least among some people who are targeted by these projects. Quoting David Sims again: “In fact, it often appears that Egypt’s desert is the playfield where a new Egypt can be created to counter the backward, chaotic, overcrowded, and hopeless mess that the old Nile valley and delta represent” (Sims, D., 2015). This is not hence a simple extension of the valley (or invasion), both in terms of planning or of mental imagery.

Regardless of the source of the images of nature and the utopia, we argue that they have an implication on the spaces of representation of Egypt itself, at least among the wealthy whom they target. With the creation of pleasant urban and ‘natural’ constructed realities and the continuous bombardment of their virtual images together with the visible deterioration of the urban environment of the valley, the balance is flipping. To this segment, the valley-desert dichotomy is probably already reversed. If Seth of the desert used to represent chaos, disorder and statelessness then, for some people, now he fits more as the ruler of the valley.

Advertisements often use a degraded image of the valley space to sell their products. They tend to sell liveability, nature, order and cleanliness as an alternative to the chaotic, stateless, polluted city dwelled by the rabble. Apart from being exaggerated and sometimes unethical marketing, and despite that some truth lies in this image, it is important to observe the direct impact of these marketing techniques. More research is needed to prove that. If true, then the desert will become a space of inversion and exodus rather than of invasion.

12. Screenshots of a Mountain View gated community Television advertisement (2015). The campaign represented some Cairo residents as rabble. It also caricatures their audience as being threatened of transforming into hulks if they continue to live in the chaotic city.

The New Desert

This whole process of invasion and/or inversion should also point to the existence of some conditions. In order to prepare the desert space for these new images, it has to be reconstructed to clear any old conceptions about it, including its harsh nature. Therefore, we propose that a process of de-naturalisation and de-historisation has either taken place or is on course to neutralise both the physical and the mental space of representation of the desert.

The desert has to be treated as a natural and historical vacuum to host such projections. At the same time, space (of gated communities and billboards) has to be isolated from the reality of poverty and scarcity – and from the social reality – as it appears in the old land(s). This resonates with what Lefebvre described as the Capitalist Mode of Production (CMP). The CMP is a threefold process of homogenisation, fragmentation and hierarchisation (Lefebvre, H., 1980). Staying with Lefebvre, images of desert development should also transform state space through the transformation of its spaces of representation.

Conclusion

Real estate billboards in Cairo advertising new developments in the desert have significantly increasing in count and density in the past few years (post 2011). Promises made by those advertisements are usually based on what the old valley is not providing anymore. Access to green nature as an example of urban scarcity is one of the main elements promised in such advertisements. Paradoxically, billboards obscure greenery and light in the city, and new parks in the desert exhaust the already limited water resources, and both contribute to further the scarcity in the old valley. In that regard, the urbanisation of the desert, nevertheless expected, can be considered a state tool to manage this struggle over scarcity. Yet, within this process, we argue that the mental image of national territory is also under reformation.

Billboard messages may have an effect on the Egyptian state space through influencing its spaces of representation. The original nature and connotations of the desert are deliberately expelled to the favour of the new modern, utopian images that often import foreign imagery and lifestyle. This cannot occur without redefining the national territory through homogenisation, often inverting the dichotomy of the valley and the desert.

We tend to believe that the process of inversion of the mental spaces of representation is happening deliberately and consistently via the agency of the state institutions, and in collaboration with private sector and real-estate developers. However, we question what will happen to the old core of the city, will it become gentrified or neglected? It is very difficult to predict the distribution of the wealth across the city, especially with the constant push towards the desert.

Privileging the desert over the valley is evident, both in imagery and natural resource distribution. This indicates a high level of inequality since most new desert city dwellers are already the economically privileged, while the old valley – where the majority still lives – is being exploited and demoted. It is not clear where this direction may lead, however, the question of sustainability will be central to further research on the future of desert developments and their representation.

While we are concerned with inequality in terms of services provision, we are also worried about the general quality of urban life inside and outside the city of Cairo. It seems that consuming nature is an alluring reason for deserting the city and inhabiting the desert; paradoxically with the aim of creating a new-found land of utopic constructions of what nature should look like. The stark contrast between Egypt’s geological, geographical and urban realities and what it ought to become is quite impressive if we think of what the billboards are attempting to sell. It brings us to the notion of human power as superior and a conqueror, and nature as a subservient object at its disposal.

Whether we like it or not, technology has helped humans achieve many previously thought to be impossible tasks (for example, watering the desert). But the question is, would these newly established social structures continue to sustain their aspired lifestyles? Will the new desert communities manage to remain ousted from the old city for long? Will they bear the hardships of isolating themselves from the heart of the city; or will they construct a new collective identity to relate to?

The billboard effect, we argue – as mentioned in our introduction – is not only physical and mental, but it also relates to self-actualisation and the construction of a new collective social identity. What stands to question is what this identity is, and how detached it is from reality.

Notes

1. footnote 1: We define social and urban segregation as the separation between different citizens in the same city into different spatial zones based on ethnic, class or gender differences. In this case, it is class-based segregation.

2. footnote 2: Elements of nature we define as Air, Water, Soil, Greenery and Light. Also Lefebvre uses a similar scope for his definition of nature. Reference below.

3. footnote 3: The valley space in Egypt is the space geographically formed and directly affected by the Nile. It is a lower irrigable land sharply distinguished from the vast higher arid desert around. Egypt’s Topography is described as: The total area of the Arab Republic of Egypt reaches nearly 1.002.000 KM2, while the populated area reaches 78990 km2 representing 7.8% of the total area. (Source: Egypt’s State Information Service http://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/2?lang=en-us).

4. footnote 4: In his Doctoral Thesis on The Development of urban and rural housing in Egypt, Omar A. Azzam described it as “The valley separates two very distinct types of country. The Libyan Desert, to the west, consists of high, flat plateaux, which drain into closed-in depressions. The Arabian Desert to the east is a plateaux of low mountain ranges adjacent to the river”, (Azzam, Omar A., 1960).

5. footnote 5: Feddans is a unit used in Egypt and is equivalent to 1.038 acres.

6. footnote 6: The road is Al-Orouba street (named Salah Salem in the southern section) which leads to the airport. It is good to note that many of its commuters are probable customers for the new desert developments as the area is considered rich.

7. footnote 7: Both surveys were done during March and April 2016. Results of our survey is strictly bound to that timing because billboards change continuously.

8. footnote 8: New Cairo was established in 2000, by presidential decree (191/2000). It is 15 Km far from Al-Maadi (South Cairo) and 10 Km from Nasr City (East Cairo) (Source: http://www.newcities.gov.eg/english/New_Communities/Cairo).

9. footnote 9: The survey measured the ratios of areas allocated to the three residential typologies which reflects economic abilities of the dwellers: gated communities, private houses, and social housing. Non-residential services and main roads were excluded. A sample from each typology was taken to calculate an estimate of green area share per resident. It was assumed that a household accommodates 5 persons which is the national average.

10. footnote 10: The survey measured the ratios of areas allocated to the three residential typologies which reflects economic abilities of the dwellers: gated communities, private houses, and social housing. Non-residential services and main roads were excluded. A sample from each typology was taken to calculate an estimate of green area share per resident. It was assumed that a household accommodates 5 persons which is the national average.

References

– Adham, K., 2005, Globalization, Neoliberalism, and New Spaces of Capital in Cairo, Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, Vol. 17, No. 1 (FALL 2005), pp. 19-32.

– Azzam, O., 1960, The Development of urban and rural housing in Egypt, Doctoral Thesis, ETH Zürich. Published online at: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-000097781

– Egypt’s State Information Service website. Available at: http://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/2?lang=en-us [Accessed 13 July 2017].

– Ghannam, F. 2014. The Promise of the Wall: Reflections on Desire and Gated Communities in Cairo. Jadaliyya, [online] Available at:

<http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/15864/the-promise-of-the-wall_reflections-on-desire-and-> [Accessed 5 May 2017].

– Heidegger, M., 1952-1962. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Translated by Lovitt, W. 1977. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.

– Hemdan, G., 2001, [The character of Egypt], vol. 1, دار الهلال [In Arabic].

– Kingsley, P., 2015, A new New Cairo: Egypt plans £30bn purpose-built capital in desert, The Guardian Cities section. Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/mar/16/new-cairo-egypt-plans-capital-city-desert. [Accessed 10 July 2017].

– Kuppinger, P. (2004), Exclusive Greenery: new gated communities in Cairo. City & Society, 16: 35–61. doi:10.1525/city.2004.16.2.35

– Lefebvre, H., 1964-1986. State, Space, World: Selected Essays. Translated by N. Brenner, S. Elden, 2009. University of Minnesota Press.

– New Cairo Authority website. Available at: http://www.newcities.gov.eg/english/New_Communities/Cairo) [Accessed 13 July 2017].

– Piper, K., 2012. Revolution of the Thirsty. Places Journal, [online] Available at:

<https://placesjournal.org/article/revolution-of-the-thirsty/> [Accessed 5 May 2017]

– Sims, D., 2015. Egypt’s Desert Dreams. AUC press.

– Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative, 2013, What Egyptians go through to find pure drinking water!

Available at: http://www.tadamun.co/?post_type=initiative&p=2868&lang=en&lang=en#.WWYM54iGOUk) [Accessed 13 July 2017].

– Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative, 2014, The Right to the City in the Egyptian Constitution. Available at: At: http://www.tadamun.co/2014/02/16/the-right-to-public-space-in-the-egyptian-constitution/?lang=en#.WWYI7YiGOUk [Accessed at 10 July 2017]

– Zaazaa, A., Borham, A., and Abotera, M., 2016. Maspero Parallel Participatory Project. [e-book] Cairo. Available at: issu <https://issuu.com/> [Accessed 5 May 2017].

+

This article was first presented at Warwick University 3rd Graduate Conference “(Dis) Assembling state spaces: Conceptualising geometries of power”, 20-21 May 2016, Coventry, UK. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations.

Mohamad Abotera was trained as an architect with both a professional and an academic career. He finished his MA in Architecture, Globalisation, and Cultural Identity at the University of Westminster in 2007. Currently, he is a PhD candidate at the University of Antwerp with a project on hegemony and tactical urbanism. His activities include academic teaching and research, cultural project management, and architectural consultations. In 2011 he co-founded Madd platform; an architecture and research collective connecting with other grassroots’ movements to promote and experiment new models of urban development. In his research he is interested in the political dimension of space, unplanned urbanism, representations and urban activism.

Safa Ashoub is a trained political scientist and urbanist. She holds a double master’s in International Cooperation and Urban Development at the Technical University of Darmstadt, Germany & University of Rome II, Italy (2008-2010). She also received a third master’s degree in Politics and International Relations (with focus on urban social movements) at the University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom (2012). She has worked for the German Development Cooperation (GIZ) for 7 years working in informal settlements upgrading. She has done extensive (urban) field research in Egypt. She also worked closely with local and national authorities in Egypt and other Arab states. Currently, she is working as a regional coordinator for the UN-Habitat for a Public Space programme in the Arab states where she is responsible for a number of public space projects in Tunisia, Lebanon, Egypt, Jordan and Palestine. Her research interests include social movements, alternative governance, urban activism and politics of transition.

Volume 1, no. 3 Autumn 2017