Diagonal Futures: remarks on a contribution to utopian thought by John Hejduk

– Michael Jasper

-

Abstract

This paper comments on John Hejduk’s introduction of a diagonal method to city design. It does this by analysing a previously unpublished manuscript sheet by Hejduk from the 1960’s. The paper also speculates that the formal opening offered by Hejduk’s use of the diagonal, and the notion of peripheral tension applied to the urban condition, can be seen as a contribution to utopian thought in architecture. Hejduk’s approach, it is argued, results in a kind of freedom different from that found in other architectural models of utopia. Characteristics of city morphology, space, and time as revealed in Hejduk’s drawings and notes are proposed as distinguishing characteristics and composition devices. A transcript of the manuscript sheet used in the analysis is provided in an Appendix.

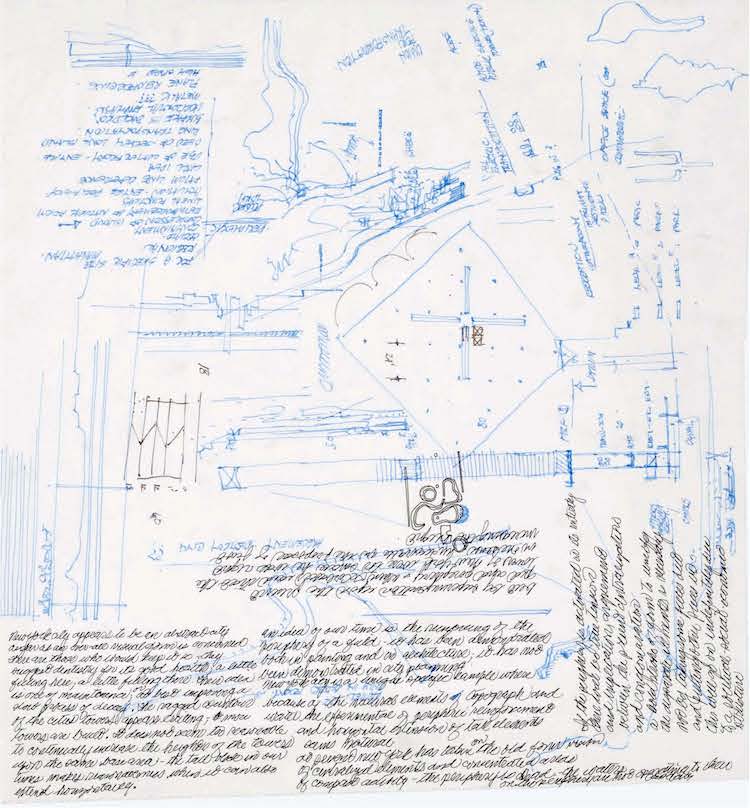

1. Miscellaneous Diamond House Sketches, drawing dr1998_0063_006 © John Hejduk Archive, Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Center for Architecture, Montréal

Introduction

Secondary scholarship on the early decades in the career of architect and educator John Hedjuk (1929-2000) has largely focused, and with justification, on his house projects. His work up to that moment, and certainly looking at the immediately preceding Nine-Square “Texas” House series, focused on the isolated building, orthogonal relations, and on trabeation at the scale of a single building. The mid 1960’s however are dense with ideas, Hejduk’s Diamond Project series are underway marking a shift in the architect’s work, and the city is in the air and on the boards as a domain to work on as a project with almost utopian leanings.

Unpublished drawings and notes from the 1960s reveal Hejduk exploring composition devices – including the diagonal and perimeter reinforcement – extended to the scale of the city. While other material may come to light, this paper will focus on the analysis of a manuscript sheet held in the John Hejduk Archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal. (Figure 1) Hejduk’s investigation of the diagonal and the perimeter is worth examination as a contribution to secondary scholarship on this unexplored aspect of Hejduk’s work. It should be done, however, in the context of the turn to city-scale meditations and the period’s engagement with the city and the modernist utopian tradition in particular. As discussed below, 1960’s debate in the academy and in practice around questions of utopia ranged from the conjectural at the level of project to the historic and scholarly. In order to frame the reading of Hejduk’s work, four questions organise the analysis:

-

a) What is at issue in Hejduk’s reflections on the grid and towers and the waterfront periphery of New York City in that particular moment of intense drawing and thinking circa 1965?

b) What are the implications of introducing a diagonal condition – already experimented with in painting and in architecture at the scale of individual buildings according to Hejduk – into the form and image of the city as a whole?

c) In front of that new city image, and assuming a highly qualified interpretation of an architecture of utopia, what are the characteristics of city form in Hejduk’s contribution to utopian thought?

d) What might looking back to more free spirited, utopian thinking reveal about architectural-urban possibilities still unrealized today?

In the remarks that follow, this paper begins to address questions a to c by focusing on Hejduk’s meditations as contained in the CCA drawing and set out element to future research around question d.

Background

Colin Rowe has argued that every architectural image or form of the city contains within it an aspect of utopian thought. This is to adopt Rowe’s claim that ‘Utopia and the image of a city are inseparable.’ In the comments that follow, I suggest that at this specific moment in Hejduk’s work, Hejduk brings into focus one aspect of utopian thought, and even more, that he thus marks a difference to other manifestations of that utopian compulsion inherited from previous generations of modern architects. At a preliminary level, the following thus concerns a proposal about potential futures of the city, and – a proposition requiring deeper inquiry -, that in his modest notes and in the context of his work on the diamond series, that Hejduk evokes a city image different from that of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse and different from that ‘mechanistic, vitalistic’ city of the Futurists, to take two of modern architecture’s standard images of the city. I also suggest that these ‘manifestations’ of Hejduk’s thought, if not in the strict sense utopian, should nonetheless be qualified as ‘a compliment to Utopian thought’, one not yet fully examined and of which the following suggests certain lines of investigation and reach.

To begin calls for a reference to Mondrian and to Le Corbusier, constant and parallel engagements in Hejduk’s work at this time. Both Mondrian and Le Corbusier are concerned specifically with the city as a privileged realm of plastic experimentation. As Hejduk acknowledges in his conversations with John Wall some two decades after the CCA drawing, Hejduk was working through his debt toward, and trying to go beyond, the utopian engagements and predilections of Mondrian and Le Corbusier. This ‘going beyond’ is a general state and alludes specifically to the multiple trajectories of modernist architecture that Hejduk was working to confront and, to take him at his word, ‘exorcise’.

For Le Corbusier, it is not to his city projects specifically that Hejduk turns at the time, but to the singular architectural effects of freedom found in the plan libre, the Domino diagram of infinite extension and adaptability, the manipulation of geometric forms, and a shaping of circulation movements that create specific kinds of space expanded to the scale of the city as a whole. For Mondrian, it is the absolute realism of his working method as much as the concrete plasticity of the paintings – representing the end of Modernism for Hejduk– that is at play. This painterly specificity should be seen as giving shape to a dream of a future life of ‘pure plastic problems’ given expression in colour and form relations.

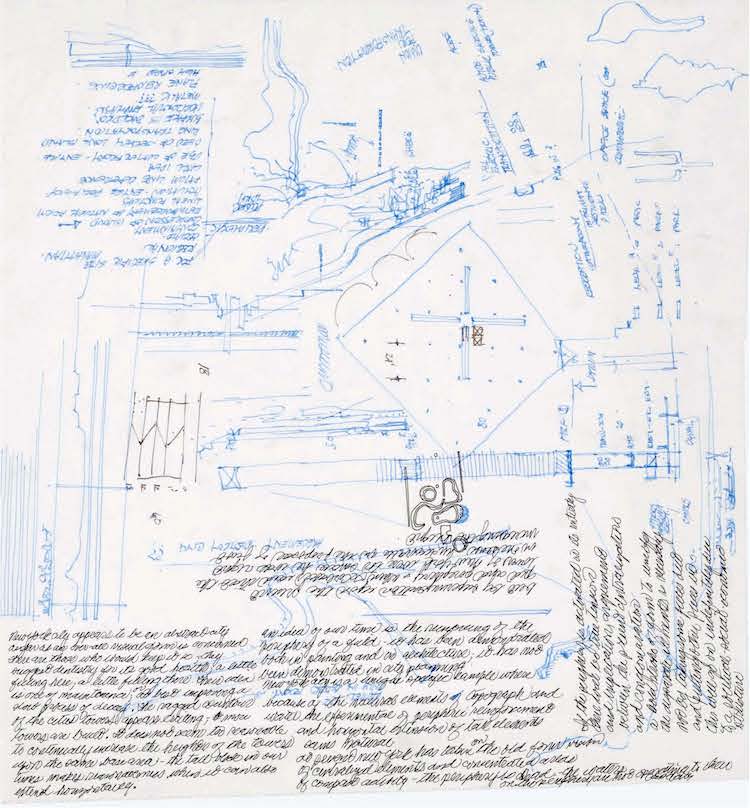

2. Diamond House A, Second Floor Plan © John Hejduk Archive, Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Center for Architecture, Montréal

Future

The form of Hejduk’s future, to take the most insistent aspect of the CCA drawing, is one characterized by diagonals and perimeters. Hejduk reflects that ‘an idea of our time is the reinforcing of the periphery of a field – it has been demonstrated both in painting and in architecture; it has not been demonstrated in city planning.’

There are two devices, two effects needed to reinforce or animate the periphery of the field in this specific model. The two devices or formal moves are that of peripheral tension and horizontal expansion and they are proffered by Hejduk as leading to a city image different from traditional ones characterized by centralization and concentration. Both devices are under investigation during his five-year experiments with diamond configurations (Figure 2). The effect or consequence of the animation of the perimeter, discussed at length in Hejduk’s Diamond Thesis of 1969, is to heighten time, to intensify the present, the diagonal relation creating the ‘most intense, most collapsed, fastest time, that of the present’ as described by Hejduk:

-

The place where a perspective or diamond configuration on the horizontal plane flattens out and the focus moves to the lateral peripheral edges…. This is the moment of the hypotenuse of the diamond: it is here that you get the extreme condition, what I call the moment of the present. … It’s here that you are confronted with the flattest condition. It’s also the quickest condition, the fastest time wise in the sense that it’s the most extended, the most heightened; at the same time, it’s the most neutral, the most at repose.

Hejduk’s city diagonal is not that of Haussmann’s Parisian boulevard, cutting, intercepting, and interpenetrating. It takes on a different form relation, one that is more about simultaneity or superimposition. In this regard, it reflects a specific moment in Hejduk’s thinking, adopting a form idea that is neither the interlocking of a European nor the isolation of an American tradition. In an interview published in 1985, Hejduk describes these two traditions:

-

Architecture of optimism”! Light was going to pour in, health was going to be good for all! …. It was very utopian – a light filled, optimistic view of the future. Now, there is another tradition, which I would say is a particularly American phenomenon. Where European architecture and urban space were always interlocking … Wall: Interlocking profiles … Hejduk: Yes, all that interweaving of volumes and cubes. But the “American phenomenon” had to do with a breaking down into units, into objects.

And he continues: ‘This breaking down into independent units, this achievement of ambiguity through the complete isolation of elements is, I might say, the American phenomenon, whereas Europeans achieve ambiguity through interlocking elements.’

The reality of form relationships in architecture at this time was so powerful that a call for ideal form imposed itself on Hejduk’s thinking and drawing. Part Mondrian of the diamond paintings, part Le Corbusier of the Carpenter Center and the Villa at Garches, Hejduk felt compelled to speculate on the ideal of a city determined by the diagonal condition.

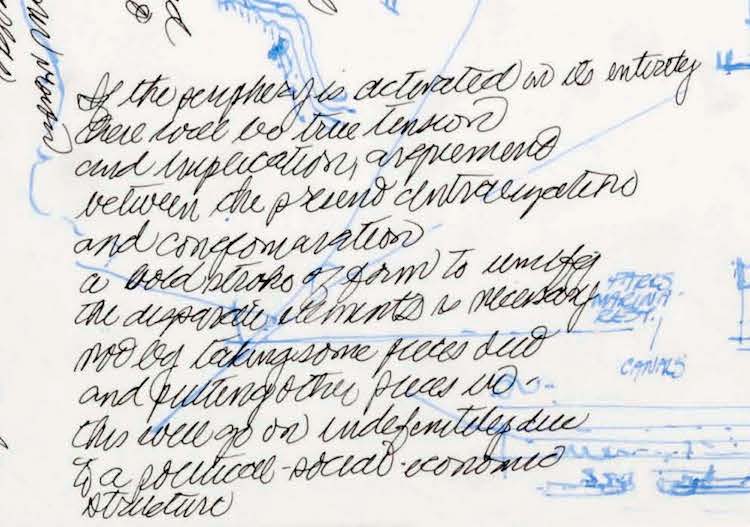

3. Miscellaneous Diamond House Sketches, drawing dr1998_0063_006, detail © John Hejduk Archive, Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Center for Architecture, Montréal

Influences

As suggested above, Mondrian was a constant occupation for Hejduk in those years. And the dream of a future of pure plastic relations, a realm of cubistic and neo-plasticist relations a constant refrain. Mondrian gives a concise formulation of the position in his last essay, A New Realism:

-

The action of plastic art is not space-expression but complete space determination. Through equivalent oppositions of form and space it manifests reality as pure vitality. … The metropolis reveals itself as imperfect but concrete space-determination. It is the expression of modern life. It produced Abstract Art: the establishment of the splendour of dynamic movement.

The city, specifically the metropolis of New York for Mondrian, realizes at an urban scale the action of plastic art. This is why for Hejduk, the suggestions and sensibilities of that ‘last realist’ – the Mondrian of Victory Boogie Woogie -, are so immediate. And at the same moment, Hejduk’s experience of Le Corbusier’s Visual Arts Center, opened in 1963 and the object of the latter’s Out of Time and Into Space article, collapses historical time forever, removing that logical, linear sequence of Cubist to Neo-Plasticist thinking into a permanent present which seeks to combine – so difficult in architecture according to Hejduk – these two space ideas.

The concept of urban space evoked by Hejduk in these notes is one of simultaneity. It is distinguished from ideas of interlocking and isolation. The approach to unifying the image of New York City, he writes, should be that of ‘superimposition’ and specifically ‘superimposition upon the present grid and periphery.’

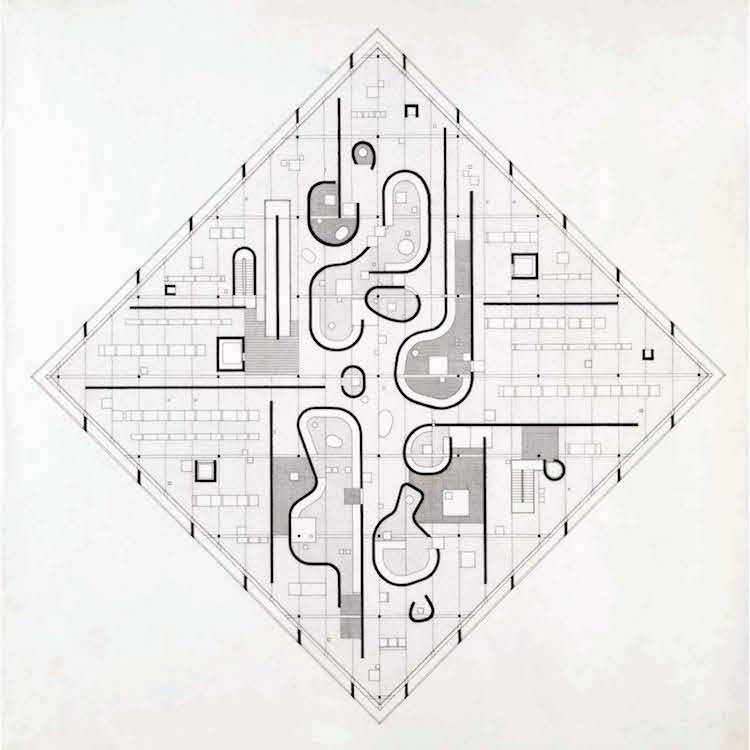

But what of the overall concept for the city? Or, to take Hejduk at his word, what of that ‘bold stroke of form to unify the disparate elements’? (Figure 3) Does it take on the figures and devices of Diamond Museum C, for example, almost certainly underway at this moment? (Figure 4) Certain of the sketches on sheet dr1998_0063_006 recall or announce elements and relations of Diamond Museum C: biomorphic shapes whether in plan or intended to announce profile, a lateral structure of horizontal extension with fluctuations, frontal alignment, and directional emphasis. These were later deeply examined by Hejduk in his 3/4 Series, Extension House, and Grandfather Wall House projects.

At this same moment, Hejduk also takes over singular elements from Rowe and Slutzky’s article on transparency, published around the time Hejduk’s notes were written. Hejduk is not engaged, however, by the visual aspects of the transparency question. Rather his interest in the Rowe and Slutzky article, as Hejduk specifically states in Out of Time and Into Space, is in the spatial order. Hejduk is interested, that is, in that seductive idea of flattened space and the notion of simultaneity now taken to the scale of the urban. This interest confirms a transformation in Hejduk’s attention, engaging full on the implications and effects of architectural freedoms, those of ‘liberated space [and] liberated structure’ expanded to the scale of the city. These in turn are marked by a desire for ambiguity and oscillation that Hejduk sought to give architectural expression to, further differentiating the aspects of this city-form idea, germinal as it is and largely remains from others available.

To that extent and in their differences, Hejduk’s notes and contemporary diamond series drawings, display optimism about the future, at least as regards the architect’s ability to contribute to it, as a way, that is, for architectural ideas to be given form and meaning. This is shown in his approach to a new form vision for the city, one no longer biased toward or based on a centralized or compact plan image, and thus in a different relation to the circle and the square, the later rotated into a diamond and then collapsed to create the sought for ‘true tension’: the new city condition is one of being always already on the periphery.

An endlessly reinvented present, that of the individual imagination, the art of composing a building, and the city as combinations of form and space giving plastic expression to an idea: these are all efforts of thinking through architecture and its utopian promise. And in this, and returning to the anecdote which opens this section, these efforts share Mondrian’s matter-of-fact faith in the present. Such a position I would argue is also revealed in Hejduk’s absolute engagement with the present, an engagement in which the architect’s dream of his/her building as image of the ideal society and of the architect as agent of bringing about change are, if not exactly reversed, then certainly no longer in place.

Diagonality

Perhaps utopia has a plastic future, one of pure plastic and color relations. That would give to Hejduk’s meditations – somewhere in the 1960’s and amid his explorations of the diamond configurations – a city image different from that of the Ville Radiuse and the vitalistic city of the futurists to recall again the priority of place given to these by Rowe. And if is a different city image, then is it necessary to claim Hejduk’s city to be the plastic corollary to a limited number of compositional decisions in form and space while at the same time acknowledging it is related to and allied with a limited set of abstract speculations.

Hejduk’s speculations could be paired with Rowe’s reflections, including the latter’s emphasis on the ambiguity of it all:

-

So there are no criteria which cannot be faulted, which are not in continuous fluctuation with their opposites. The flat becomes concave. It also becomes convex. The pursuit of an idea presumes its contradiction… The myth of Utopia and the reality of freedom!

From his 1973 appendix to “The Architecture of Utopia”, fourteen years after the article’s original publication, Rowe’s ‘continuous fluctuation’ could be used to describe the state of the city filtering through Hejduk and others at that time. Ambiguity is a positive value, and freedom it’s corollary, but now given the challenge of finding physical expression and thus the engagement with questions of stability and permanence and with formal characteristics swinging between the static and the dynamic. This suggests that the dual identified by Rowe – between ideas of form, space, time, and city image – found perhaps a specific focus in architecture’s pronouncements for a short moment, including that of Hejduk: utopia, freedom; myth, reality. And the movement – real enough for some, but for most a problem in the realm of the ideal – of flat to concave or convex was all part of an intense optimism about the present.

To that extent, and recognizing the internal inconsistencies of pronouncements and the general absence of further elaborations, at this moment Hejduk might be said to display an optimism about the future that is so intense that it’s the present, in the end, that is approached as the most concrete condition of the future.

This can be shown in the coupling of physical expression and the time idea contained in Hejduk’s description of the workings of the diamond configurations. Hejduk claims the latter are configured in such a way as to create that ‘moment of the present’ as a singular characteristic of our time. It is a time that is no longer the past time of the Renaissance nor the time of the Cubists. It is created, according to Hejduk, or its potential opened, by specific composition decisions that result in ‘reinforcing the periphery of the field’, to return to that short hand annotation in Hejduk’s manuscript.

4. Diamond Museum C, Floor Plan © John Hejduk Archive, Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Center for Architecture, Montréal

Conclusion

This returns us in the analysis to the ‘moment of the present… the most extended, the most heightened’ that comes out of ‘reinforcing the periphery of a field’ as Hejduk was to describe so eloquently in the form and space experiments of the Diamond series. (Figures 2, 4) This moment of intense hope, or better of an intense present, provides an illustration to aspects of a form of utopian thought in architecture, one that seems still open and possible today.

Hejduk’s musing did have its contemporary manifestations. Peter Eisenman and Michael Graves’ 1966 project for the Manhattan Waterfront realized an extreme peripheral tension on both the Hudson and East River edges. The plan and images as published show explicit horizontal extensions with dramatically extruded north-south bar buildings extending over ten blocks. The entire composition is unified by the superimposition of a number of multi-block diagonals. In this regard, the project provides a near exact illustration of Hejduk’s musings.

Further examples can be found in Rowe’s efforts with students in the Cornell Urban Design Studio in the same years 1965-1966. Two projects, a redevelopment proposal for central Harlem (part of the same exercise organized by the Museum of Modern Art to which the above Eisenman/Graves’s solution responds), and a study for the Buffalo Waterfront, stand out. The later project stands out in its manipulation of the grid, diagonal overlays, waterfront perimeter, and engagement with and transformations on the ideal model: these are derivations on Utopian speculations that resonate particularly with ambitions for a utopia of accommodations. In this, elements of what Hejduk’s New York City might have looked like are suggested.

The future is likely a concern, but for Hejduk it is the present that is forever in front of his image of architecture and the city. A pragmatic, matter-of-fact approach that provides for a way of living that is open, assuming we can equate that formal opening offered by the diagonal with a kind of freedom different from those of the traditional city, the city in the park, and the city as mechanical utopia. And the device of the diagonal method becomes one characteristic for differentiating the specificity of the ideas of freedom and the present in his work.

The city image implied in the notes of Hejduk is in summary distinguished by three characteristics: — the diagonal, which supplants the circle of Renaissance models; — horizontal expansion, different from vertical, tower visions; — superimposition or simultaneity and thus a real desire for ambiguity in lieu of the static grid with isolated elements or a stable, interlocking form.

A desire for ambiguity – as Hejduk alludes to and Rowe more specifically discusses – which might be here translated as architectural freedom, underlies it all. And suggests that Hejduk, somewhere in that rush of the 1960’s, answered the call to reflect on some ‘bold stroke of form to unify the disparate elements’. Implications still to be explored as we move toward an endlessly deferred utopian city as the most concrete condition of the future at least as it can be imagined by the architect, with its characteristics forms and urban space.

The city had become a realm to be healed, treated not however by small gestures within the existing pattern, Hejduk’s negative model of ‘taking some pieces out and putting other pieces in’. A larger move was called for and the response set out in Hejduk’s notes provides a contribution, modest, to specifically architectural work on utopia and the image of the city.

Rowe, in a near contemporary article, summarizes the position: ‘The Modern building was both a polemic and a model, a call for action and an assertion of those ends to which action should lead; and therefore it is not surprising that the architect should have often conceived of his buildings, not only as the images of a regenerated society, but also as the agents which were destined to bring that society about.’ And while Rowe records a ‘certain deflation of optimism’ circa 1965, his present is not the future hoped for, he does leave open the possibility that the ‘aspirations of the 1920’s’ may yet be realized. And it is in that sense perhaps that Hejduk’s thinking and city images, even if yet to gain that level of abstraction and notoriety as to be recognizable even in fragments in subsequent decades, suggest that research and exploration on utopian impulses is still called for. Our recent and current history, no matter how clouded, contains elements that might still lead to that ‘good-place’, or provide ongoing momentum to work toward it, and in that sense it is timely to re-examine such moments.

-

Appendix

The following is a transcription of the notes from a manuscript sheet held at the Canadian Center for Architecture, Montréal, used in the above analysis.

New York City appears to be an abstract city as far as an overall visual form is concerned. There are those who would keep it so; – they suggest dentistry for its good health; a little filling here, a little filling there. Their idea is one of maintenance; or at best improving a slow process of decay. The ragged contour of the cities towers appears exciting, – more towers are built. It does not seem too reasonable to continually increase the heights of the towers upon the same base area – the tall block in our time makes reasonableness [sic] when it can also extend horizontally.

an idea of our time is the reinforcing of the periphery of a field – it has been demonstrated both in painting and in architecture; it has not been demonstrated in city planning. New York city is a unique specific example where because of the natural elements of topography and water the experimental [sic] of peripheric reinforcement and horizontal extension of tall elements seems natural. At present New York has taken on the old form version of centralized elements and concentrated areas of compact activity – the periphery is dead, – the waters on the periphery are not operating to their capacity.

If the periphery is activated in its entirety there will be true tension and implications, a replacement [?] between the present configuration [?] and conglomeration

a bold stroke of form to unify the disparate elements is necessary not by taking some pieces out and putting other pieces in – this will go on indefinitely due to a political-social-economic structure

but by superimposition upon the present grid and periphery – when Le Corbusier said that the towers of New York were too small he was right in one sense inaccurate in the proposal of just increasing the height.

//

For a specific site Manhattan | Regional | Social | Containment | Compression of island | Reinforcement of natural form | Lineal functions | Activation – Entire periphery | Datum line reference | Wall idea | Use of waterfront – entire | View of Jersey Long Island | Ring transportation | Surface as backdrop | Horizontal emphasis | Metalic??? | Plane reinforcing | High speed

John Hejduk, c. 1965

John Hejduk Archive/Fonds 145, Sub-file 4: Miscellaneous Diamond House Sketches, drawing dr1998_0063_006 © John Hejduk Archive, Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Center for Architecture, Montréal

References

– Aureli, Pier Vittorio, Biraghi, Marco and Purini, Franco, eds. Peter Eisenman, Tutte le Opere. Milano: Mondadori Electa, 2007.

– Caragonne, Alexander, ed. As I Was Saying. Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays. Volume Three, Urbanistics. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1996.

– Eisenman, Peter. “In My Father’s House are Many Mansions”, in John Hejduk: 7 Houses (New York: Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, 1980): 8-19.

– Frampton, Kenneth. “Notes from the Underground”, Artforum 10 (April 1972): 40-46.

– Hejduk, John. “Out of Time and Into Space.” A+U 53 (May 1975): 2, 4, 24,

– Hejduk, John. John Hejduk: 7 Houses. New York: Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, 1980.

– Hejduk, John. Mask of Medusa: Works 1947-1983. New York: Rizzoli International, 1985.

– Holtzman, Harry and James, Martin S., eds. The New Art – The New Life. Boston, G. K. Hall & Co,1986.

– Jasper, Michael. “Working It Out: On John Hejduk’s Diamond Compositions.” Architectural Histories 2 (1)/26: 1-8.

– Mondrian, Piet. “A New Realism,” in The New Art – The New Life. The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian, edited by Harry Holtzman and James S. Martin, 348. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co.,1986.

– Pommer, Richard. “Structures for the Imagination,” Art in America, March-April 1978: 75-79.

– Rowe, Colin. The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1976

– Rowe, Colin. “Waiting for Utopia.” in As I was Saying. Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays, edited by Alexander Caragonne, 75-78. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996.

– Rowe, Colin and Slutzky, Robert. “Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal”, Perspecta 8 (1963): 45-54.

Michael Jasper is an architect, educator, and scholar based in Australia. He is Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of Canberra where he directs the Master of Architecture course and leads the major projects studio and advanced architectural analysis units. While Partner in the New York office of Cooper Robertson & Partners (2002-2011) he directed many of the firm’s major institutional and urban scale project, his clients including Yale University, Johns Hopkins, California Institute of Technology, City of Miami, State University of New York at Stony Brook, University of Miami, and Whitney Museum of American Art. He was Visiting Scholar (2015) at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and Visiting Scholar (2013) at the American Academy in Rome. He is the author of Architectural Aesthetic Speculations: On Kahn and Deleuze (2016) and Deleuze on Art. The Problem of Aesthetic Constructions (2017).

Volume 1, no. 3 Autumn 2017