Frankencities: urban horrorscapes of our near future

– Alan Marshall and Nanthawan Kaenkaew

Happy 200th birthday to Frankenstein; thrown onto paper after a night of anguished thoughts by Mary Shelley in 1816 and first published in 1818. Shelley crafted her Frankenstein novel in the style of a gothic romance; overflowing with emotional turmoil and in awe for foreboding landscapes.

Since then, though, the Frankenstein story has been refashioned many times for the screen – often losing the romance and becoming a sci-fi horror flick1. All versions, though, involve a monster being pulled into life by the heinous cobbling together of dead and dying bits and pieces of humans – and sometimes other animals — and then zapping the conflated mass with electrical energy.

After being electrified into life, the monster then suffers a series of rejections; firstly, from his creator, Dr. Victor Frankenstein, and then from pretty much the entire human world altogether. These rejections drive the creature into despair and then onwards into a murderous campaign of revenge. For those reflecting upon the Frankenstein story2 the following themes are usually held to be important:

-

Techno-Hubris. The fervent labors of Dr. Frankenstein–as he obsessively pursues his goal of creating life–is a cautionary tale against the arrogance of technological discovery. Shelley’s novel exhorts explorers and discoverers and adventurers not to become so mesmerized by the heroic importance of their projects that they overstep the bounds of Nature or social responsibility.

Alienation and abandonment. After casting his creature onto the world, Dr. Frankenstein then runs away from it as quickly as possible. He was originally intent on making a superhuman marvel but Dr. Frankenstein had gotten it very wrong—and the people that encountered his creature usually wanted to beat it away with a stick. Frankenstein’s creature becomes alienated from humanity and any form of social care just because of its frightful visage.

Monstrosity. Dr. Frankenstein’s creation is monstrous; an inartistic unwieldy assemblage; whose figure is humungous and whose strength and stamina is superhuman. But the theme of monstrosity is not confined to the monster itself. As the story unfolds, the ‘monstrosity’ theme is transferred by Mary Shelley back onto Dr. Frankenstein–whose irrepressible feelings of horror and hatred slowly transform him into a monster as well. Frankenstein ends up stalking his creature across the whole of Europe in order and kill it.

Now, what follows is an application of these ‘Frankenstein themes’ to the urban form. We do this in the belief that Shelley’s Frankenstein — though 200 hundred years old — may well provide a pathway to predict the character of our cities as they change over the near future.

To accomplish this, we could’ve selected a series of cities noted for their global importance, or we could’ve selected a series of cities noted for their influence in the invention and adoption of new technologies. Instead though, we’ve selected three cities that appear in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This is fitting, in a way, since Frankenstein is not only a gothic novel, it’s also a travel story with a keen geographical sense. Like other writers in the English romantic tradition, Shelley provides eloquent descriptions of real places through which she had toured or within which she had lived.

Franken-Naples: city of radioactive inferno

Mary Shelley writes of Victor Frankenstein being born in Naples in the late 18th century; the son of a distinguished Swiss family. His parents were supposedly residing in Naples as part of an extended tour around the Italian peninsula. This fictional history is consonant with the true-life travels of Shelley and her husband, the poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, who together stayed in Naples in 1818/1819 (figure 1).

Whilst the Shelleys came from quite distinguished families themselves, their lifestyle in Naples was far more Bohemian than that of the fictional Frankenstein family—filled as it was with extramarital affairs, run-ins with authorities, skirmishes with debt-collectors, problems with finances and ex-lovers, family feuds conducted via dark letters from afar, an illegitimate child, the death of another child, yet as well some stirring parties and dizzying sojourns across the Italian landscape3. Somehow, though, both Shelley’s found time to write.

1. Naples in the early 19th Century. Unknown Artist

Because of her experiences in the city though, Mary Shelley wrote of it: “Naples is a paradise inhabited by devils”. Percy Shelley also reflected upon Naples in a disturbed way4:

-

Naples, though Heart of men, which ever paintest

Naked, beneath the lidless eye of heaven!

Elysian City, which to calm enchantest

The mutinous air and sea! They round thee, even

As sleep round Love, are driven—

Metropolis of a ruined paradise.

By 1818, Naples had not long emerged from the Napoleonic wars as the capital of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, a regime that offered some citizens of Naples a short and rare opportunity to call themselves independent. The heroized British commander Horatio Nelson had played a major part in this since he protected Naple’s monarchs from being re-invaded by Napoleonic armies5. Alas—he also signed the death warrants of many native Neopolitan rebels, serving to mire the Kingdom in political conservatism and a regressive social order for decades.

Like many progressive thinkers of the early 19th Century Europe, Mary Shelley was in two minds about the French Revolution, since she seems to have supported its radical agenda but was fraught by the monster it had spawned in Napoleon’s European-wide dictatorship. Mary Shelley probably chose Naples as Dr. Frankenstein’s birthplace to mirror the birth of an enlightened mind that was eventually to descend into something monstrous.

Coincidentally, the Shelley’s time in Naples coincided with the coming-out of the Camorra; a once secret society that became an overt organizer of gambling and extortion in the city. Since then, the Camorra has become the regions’ predominant mafia.

Nowadays, the Camorra are generally acknowledged to be big players in the environmental problems of Naples. In the late 2000s, the city’s main municipal garbage dump, meant only for domestic refuse, was filled to overflowing with industrial waste. Much of this industrial waste was illegally brought in by the Camorra from northern Italian cities or from other nations north of Italy. In December 2007, the municipal workers refused to pick up further garbage from the streets—declaring aloud that there was nowhere to put it. As a result, the streets of Naples soon became the garbage-dumps of the city.

However, the events of 2007 pale into insignificance compared to yet another chronic waste management crisis that has been going on for decades; the dumping of toxic and radioactive waste in the countryside just north of Naples – again orchestrated by the Camorra6. Once more the waste seems to originate from the north of Italy and from northern Europe. The companies in the north that discharge the waste tend to ask no questions about where the garbage is destined just so long as it is taken off their hands. Recently it has been shown that leading politicians have known about the problem for years yet did nothing has been about it — even as the health toll climbed – with cancer clusters and lung disease rising in certain places around the city.

It is estimated that over ten million tons of toxic or radioactive waste are illegally disposed of each year in Italy by the mafia — all with suspiciously little response from the authorities. This ‘black garbage’ business involves €15 billion changing hands per year. The peri-urban area of Naples, which is the most chronic dumping-ground for this waste, has been dubbed the “triangle of death” where plants, animals, and humans, along with the groundwater, all suffer high levels of contamination. Reports in the local media abound with anecdotes of two-headed sheep, heavy metal-laced mozzarella, and radiation-drenched cauliflower.

In some spots, the garbage is piled high and set alight. During the fire-ripped years of 2007 and 2008, the entire region north of Naples was headlined in Italian papers as ‘Terra dei fuochi’ or ‘Land of Fires’ with toxic fumes billowing over Naples’ outlying suburbs.

Looking back in history beyond these disasters, and throughout all Naples’ rises and falls, the rumbling Mount Vesuvius has lain in the background. The volcano is most famous for being the destroyer of the Roman city of Pompei—but before and since, it’s devastated numerous towns nearby7. Over the millennia, Vesuvius’ explosive rocky fires and gas flows have often been accompanied by massive dark clouds that would spread thousands of kilometers over the Mediterranean, sometimes blocking out the sun for weeks on end. Luckily for the Shelleys, Vesuvius was quiet during their stay in the city — though for many of Naples’ residents, memories of the mountain’s late 19th century violent eruptions (figure 2) were still vivid.

2. Mt Vesuvius during one of its many late 18th Century eruptions. Unknown Artist

Vesuvius then and now is one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world both because of its volatility and because of its proximity to such a large city. Naples is now home to a population of more than four million.

A timeframe of one major eruption per generation is held to be the rule of thumb. If this is accurate, then Naples is sitting side-by-side with near-future catastrophe. According to the city authorities, the modern city has an emergency plan; to evacuate half-a-million ‘most-at-risk’ residents over a twenty day period. However, experts acknowledge the mountain may not give any advanced warning of its intention to erupt.

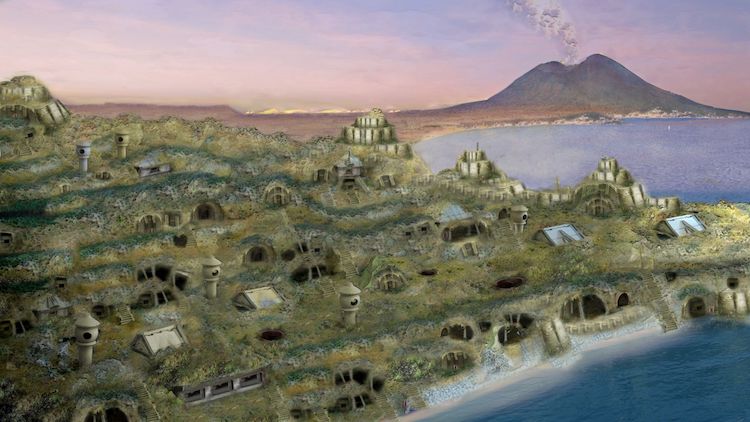

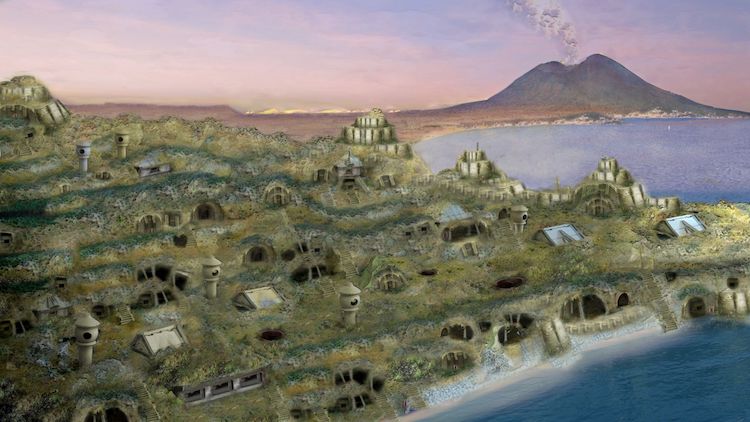

So, let’s get to the scenario presented here for a Naples of the near future, our ‘Franken-Naples’ (figure 3). Here, an unfortunate disaster has hit the city in recent years. Columns of thick deadly smoke have inundated the streets for days, then retreated, then come again, then slowly dissipated. As well as this, enormous inflamed clouds have exploded around Vesuvius sending incandescent balls across the city scape. The disruption is so severe that Naples citizens must choose from one of three alarming options: a) to ignore the fires and smoke and hope not to be hit by a hot gas cloud, b) to move somewhere else, or c) to start living underground. In Franken-Naples, these options are pursued in roughly equal proportions by the four million citizens.

3. Franken-Naples by Alan Marshall and Nanthawan Kaenkaew

As far as the third option goes, it should be noted that around 60 percent of Naples is built upon a huge subterranean city. This underground labyrinth comprises acres of caves and caverns and chambers and tunnels and passage-ways and vaults and safe-houses and crypts and catacombs and reservoirs and cisterns and waterways and sewers and subways and bomb-shelters. Naples subsurface rock – a soft sufo made of volcanic ash — has made the city suitable for the construction of this vast ‘subtropolis’; slowly hewn and dug-out and mined over the city’s long history. And every year, archeologists and cavers discover even more chambers.

It is within these subterranean caverns and passage-ways, amongst the decayed or forgotten remains of old Naples, that many citizens of Franken-Naples will escape to avoid the surface chaos. Over the course of a few years, here in the underground, they develop a new troglodyte safety zone. Initially meant to be temporary, it ends up becoming a permanent home for many since it’s the only place for their skin and eyes and lungs to survive the noxious deadly clouds drifting episodically over them.

Let’s be clear, though, the crisis of Franken-Naples is not volcanic. Yes, Vesuvius rumbles gently off in the distance once-in-a-while as it has done for millennia; sending the occasional spray of smoke high into the air. But the disaster wrought upon Franken-Naples is anthropogenic. As the Camorra keep abandoning dangerous waste all around Naples’ countryside, and as the authorities continuously abandon their civic and professional responsibilities, eventually some flammable component of the dump mixes with various toxic and radioactive components, and an ensuing inferno sweeps uncontrolled over the city in repeated episodic onslaughts. In response, Naples’ citizens are continually driven to panic; running (or crawling) into their tunnels and crypts until they fear to ever emerge onto the monstrous alien surface.

Franken-Ingolstadt: the city inaudible

The monster in Frankenstein was ripped and stretched and sewn and stitched into being by Dr. Frankenstein at a university in the German city of Ingolstadt (figure 4) after he’d spent years experimenting with dead bodies and with various chemicals and energies.

4. Ingolstadt University, late 18th century. Unknown artist

We’re lead to believe by Mary Shelley that Dr. Frankenstein8 was so aggrieved by the idea of death rampaging with cruel consistency over humanity that he countenanced no shame for his criminal and sacrilegious dealings with human corpses. With what seems like an utter lack of imagination and foresight, however, at the very moment when the monster flickers into the life, Dr. Frankenstein suddenly realizes the monstrous nature of his experiments and the monstrous nature of his newly-made creature. He swiftly abandons his creation and his laboratory, and seemingly also, he abandons science and technology altogether too.

Nowadays, Ingolstadt is a city of nearly 200,000 people on the banks of the Danube in Bavaria. Appropriately, or ironically, it’s evolved into a city with science and technology at its base; filled with a multitude of technical institutions. The largest single industry in Ingolstadt is the Audi car company, which has its slogan ‘Advance Through Technology’ glossily emblazoned on its Headquarters for all the city to see. Audi prides itself, much like Dr. Frankenstein did, on pushing the boundaries of technology. Audi was the first to use aluminum chassis and Audi also pushed forward the development of water-cooled engines9.

Their most notable technological achievement in recent years, though, has been the innovation of ‘cheat software’ to run riot around the emissions laws in Europe and North America. In 2015, when the emissions scandal came out into the open, Audi admitted that over two million of its cars had been sold with the cheat software installed. Audi’s cars then went on to spew nitrogen oxide into the air well beyond healthy limits10.

Though Audi promised to quickly find a technical solution and to upgrade their cars, their head of research was fired for his part in the scandal. Like a modern-day Dr. Frankenstein, Audi’s technical guile trumped their ethical reflection. Maybe, however, this comparison is unfair since Dr. Frankenstein’s monstrous invention killed but three or four people whilst the illegal software of Audi, and their parent company Volkswagen, has been estimated to have killed hundreds or thousands11.

According to an oft-told story in Ingolstadt’s industrial history, the name Audi is a translation into Latin of the surname of the founding engineer of the company; August Horch. The story goes that Horch was hosting a dinner party for investors in 1910 to mark the launch of a new car company, so he and his guests were digging around for a suitable company name. They couldn’t use the name ‘Horch’ as it was already trademarked to the previous car company Horch had just resigned from. From the backdrop of the party, August Horch’s young son, who was doing his Latin homework, spoke up to suggest ‘Audi’ since it is a rough Latin form of Horch, both of which mean ‘to listen’ or ‘to hear’ in their respective languages. Well, at least this is the story told by the Audi company12 (but who can trust them anymore?)

Surrounding the city of Ingolstadt is a lovely riverside forest. After Dr. Frankenstein fled his laboratory, his abandoned monster eventually got to his feet and made an ungainly tour of the city’s streets. All the folk of Ingolstadt who came across him would either scream or faint or beat him away or throw rocks at him. The sturdy creature could come to no harm from sticks and stones but nevertheless he couldn’t endure the constant social rejections of the townspeople. Therefore, alienated and abandoned, he dismissed the city for the riverside forest.

Here, with only a few small villages, the river, and an expansive woodlands, the monster finds a place to settle for some months – hiding-out in a tiny run-down storehouse next to a small cottage occupied by a French family. They, themselves were also alienated from their own society, living in Bavaria as exiles from the tumultuous French Revolution.

During these months, the monster carefully and clandestinely studied the dealings and events of French family for whom he grew an affection. From his keen observations, and through no face-to-face interaction, the monster manages to learn the French language. By year’s end he becomes so good at it that he can read an array of books found left in the cottage when the family were out-and-about working.

We learn, also, that the creature had grown adept at transforming his feelings and emotions into eloquent passages, like the following lines rejoicing upon springtime in the forest:

-

The pleasant showers and genial warmth of spring greatly altered the aspect of the earth. Men, who before this change seemed to have been hid in caves, dispersed themselves, and were employed in various arts of cultivation. The birds sang in more cheerful notes, and the leaves began to bud forth on trees. Happy, happy Earth! Fit habitation for gods, which, so short a time before, was bleak, damp, and unwholesome. My spirits were elevated by the enchanting appearance of nature; the past was blotted from my memory, the present was tranquil, and the future gilded by bright rays of hope and anticipations of joy.13

What we see – here in the natural forest nearby Ingolstadt — is that the monster made by Dr. Frankenstein is not entirely monstrous. He’s capable of appreciating the arts, of admiring nature, and he’s capable of affection and care and good will to fellow villagers. He even starts to collect firewood and harvests crops in the dead of night for the cottage family; laying the wood and the harvest neatly outside their cottage. The family awakes each morning knowing not who helps them. Maybe ‘forest angels’ they conjecture.

As a ‘forest angel’, the monster is briefly lifted above humanity and in celebration of this fleeting divine moment, we arrive at the following scenario: Franken-Ingolstadt. Here (figure 5), inspirited by the creatures of the forest, the engineers of the city take responsibility for the pollution of their machines as they design and construct a bat-faced highway noise barrier.

5. Franken-Ingolstadt by Alan Marshall and Nanthawan Kaenkaew

In some places, German highway agencies have sometimes erected thin concrete barriers to limit automobile noise pollution and they’ve also studied the efficacy of vegetation to cut down the sound levels. The scenario presented here goes a few steps further. The bat-face noise barrier draws inspiration from those monstrous-looking bat species whose ornate facial organs, adorned with multi-lobed ears and fluffy whiskers, have been fashioned by evolution to disseminate and collect sound waves via bio-sonar. In Franken-Ingolstadt, the bat-faces are scaled-up in size, sculpted into 3D relief, and then mounted on the inside of an earthen barrier. From the outside, amongst the surrounding forest and villages, the auto traffic is hardly audible. But on the inside the obnoxious rumbling traffic noise is reflected straight back upon the automobiles that produce the noise.

For those drivers who may regard the bat-faces as monstrous, they also serve as a symbolic visual reflection of the grotesque noise their cars cast out onto the environment. If Audi means ‘to Listen’, then let those who drive these polluting machines hear every decibel of their thundering cacophony.

Franken-Arkhangelsk: the melting arctic capital

For Frankenstein’s monster, the promise and innocence of the nature that is the Ingolstadt riverside forest is destroyed whenever he encounters humans. One day, he rescues a child that his fallen into the river—only to be beaten. Another day, he gives food and company to a blind old man—only to beaten by the man’s relatives. Confused and distressed, the monster seeks out Dr. Frankenstein to in order to learn about himself and about humanity. But again, it does not go well—and after being yelled and beaten some more he erupts emotionally to murder most of Dr. Frankenstein’s family.

Overwhelmed with sorrow and with feelings of retribution pumping in his heart, Dr. Frankenstein, himself, transforms into something of a monster. He ends up on a protracted quest for restitution; believing that he must rid not just his family – but the entire civilized world — of his terrible invention.

Dr. Frankenstein tracks his creature all the way north through Eastern Europe and up to the Arctic port of Arkhangelsk. The monster, no dummy, knows his creator is in pursuit and he even leaves little signs in the freshly fallen snow for Frankenstein to follow—a signal of the creature’s conflicted feelings toward his maker (whom he occasionally thinks of as his ‘father’).

6. Arkhangelsk, early 19th Century. Unknown Artist

Arkhangelsk in Shelley’s time (figure 6) was called the ‘Capital of the Arctic’. From here, countless arctic entrepreneurs, traders, prospectors, whale-hunters, and adventurers set off into the islands and peninsulas and waters of the frigid Arctic Ocean—as would Frankenstein’s monster and, soon-after, Frankenstein himself.

For much of the year Arkhangelsk becomes a physical part of the Arctic ice sheet and it is often hard to see where the city ends and the icy ocean begins, such is their extent of the ice-cover. For this reason, the port must remain closed for many months of the year. More and more, though, the ever-warming Arctic Ocean nowadays laps at the sea to melt the ice so that the port of Arkhangelsk is more often able to stay open longer around the year14.

In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the final confrontation between the creator and his creature takes place on the ice floes north of Arkhangelsk. In a dramatic climax, Dr. Frankenstein walks and skids and skis and slips across the ice, toiling for hundreds of miles on sled, upon skis, and upon his own two feet. Just as he spots a blurry figure off into the distance, Dr. Frankenstein collapses from exhaustion.

The monster then turns around to recover Frankenstein before he freezes to death. Just then, a passing ship of British explorers, engaged in a voyage to the North Pole, come across the pair of them. The monster flees, and the Captain of the ship takes Dr. Frankenstein onboard for recuperation.

After a few days, and whilst the ship becomes stuck for a time in ice, the Captain resurrects Dr. Frankenstein just enough so that that Viktor can relate the whole sordid saga of his monster story. Dr. Frankenstein also warns the Captain to be weary of journeying too far North, into unknown hazards, just for the glory of discovery. He also begs the captain to beware the eerie monstrous cries of the ghostly icy ‘thing’ that both can hear through the Arctic fog, for the intentions of the monster, says Dr. Frankenstein, are unclear.

At this spot nowadays in the 21st century, where the British ship was stuck in ice-floes north of Arkhangelsk, it is more than likely that the ice will soon forever melt away. It’s also possible that in a few decades the Arctic ice all the way to the north pole will have disappeared15.

If such was the case in Shelley’s time, Frankenstein and his creature could not have had their final meeting, since no tracks would have lain in the ice for Viktor to follow–only the breaking peaks of cold salty waves.

Meanwhile, in the city of Archangelsk, there are now strange impacts arising from climate change. Russian shipping firms and Russian gas companies have embraced global warming since, for them, the growing lack of ice has opened-up shipping lanes for easier navigation. A globally-warmed Arctic also makes the extraction of natural gas less complicated and more profitable.

However, a growing concern for all northern Russian cities is the melting of the permafrost and the growth of sinkholes (figure 7). As the permafrost thaws, it becomes more fragile, and so more easily eroded by the increasing flow of subterranean water. Some of the sinkholes are huge; swallowing not only fields and cars but entire farms and town blocks.

7. Franken-Arkhangelsk by Alan Marshall and Nanthawan Kaenkaew

Another issue associated with the thawing permafrost is the reemergence of the ‘Arctic Plague’, the phrase used by Russians to describe anthrax16. As the once-frozen soil is warmed up to become soggy, the carcasses of long-dead reindeers re-emerge to spew anthrax spores onto unsuspecting locals. In recent years, hundreds of reindeer-herders have been hospitalized and many thousands of their reindeer have had to be culled and burned.

This problem is only going to get worse as increasing numbers of burial sites, both human and animal, and some dating back to the middle ages, are unearthed from the permafrost by rising temperatures which melt frozen soil, loosen rocks and stones, and thaw dead bodies. These bodies may have microbial spores hiding within them from previous epidemics; from one of the many 19th Century Small Pox outbursts, maybe. Or if the bodies date from earlier periods, they could hold the spores of medieval plagues.

Perhaps Arkhangelsk may be able to survive global warming, and survive the sinkholes, and even go on to prosper economically via the shipping and gas industries. Just as likely though, it’ll be stricken by a horrific new Arctic pandemic sweeping through the city to rapidly kill tens of thousands.

As monstrous as a new plague might be; the melting permafrost around Arkhangelsk portends an even more terrible scenario. As the permafrost of northern Russia thaws, great loads of methane gas are released. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas and because the Russian permafrost is so expansive – one of the largest terrestrial ecosystems on the planet – humanity maybe knocking on the door of a ‘Methane Death Spiral’. If this door is opened, hotter Arctic temperatures will melt more permafrost which releases more methane into the atmosphere which heats up the climate even more which melts evermore permafrost, and so on and so on. Within a few decades, an abrupt global climate change will be forced upon all the Earth17. If so, we have some truly frightening effects to look forward to:

-

– The global temperature rises by an average of 6 degrees in a decade or two.

– The global sea-level will rise by 6 meters in a decade or two.

– Some (or all) urban land space of virtually every coastal city of the world will disappear underwater.

– Some (or all) rural land near the coast will either be flooded or salt-drowned, dramatically impeding food production.

– There will be massive die-offs of entire species (including, some suggest, Homo sapiens).

All these impacts together would probably make it extremely difficult for any of the Franken-cities presented above to secure a sustainable future; and maybe their very existence would be perilous and improbable.

To temper thoughts of such cataclysm, though, we can note that whilst 97 percent of scientists believe in anthropogenic global warming, most opine that this worst-case scenario of ‘abrupt climate change’ will be stretched out over the next one hundred years rather than over the next two decades. But, like Dr. Frankenstein, perhaps their imagination and foresight is failing them.

After telling his tale to the British explorers, Frankenstein succumbs to exposure and dies. The Captain of the ship is so moved by his story, however, that he gazes northwards to the pole for a minute before turning the ship around and heading back to the Arkhangelsk.

For two hundred years, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has been warning us of the wasteful arrogance of needless technological adventures—and for two hundred years, few have listened. Will we, like Dr. Frankenstein, only realize the impact of our technologies after it’s too late? Or will we turn the ship around?

Shelley hints that the creature dies in the Arctic as well, throwing himself into the sea to drown in a desperate attempt to escape his own alienation. Yet the lines depicting his demise are ambiguous. Maybe he just walked off northwards to live on the ice at the North Pole all alone, with the unprejudiced nature of the ice-scape to keep him company.

Despite his best efforts, Dr. Frankenstein never managed to slay his monster. However, two hundred years later, after two centuries of ‘technological progress’ and two centuries of ‘social progressiveness’, we, the smarter kinder more just people of 21st century, are set to slay Frankenstein’s creature by melting away his last final refuge. What monsters have we become?

Notes

1. For detailed examinations of the similarities and differences between Shelley’s Frankenstein and the movie versions, see: R. Montillo and S.T. Hitchcock, (2007) Frankenstein: A Cultural History, and L.D. Friedmann, and A.B. Kavey (2016) Monstrous Progeny: A History of Frankenstein Narratives, Rutgers University Press.

2. As explained in: S. Bann (1997) Frankenstein: Creation and Monstrosity, Reaktion Books; J. Turney (1998) Frankenstein’s Footsteps: Science, Genetics and Popular Culture, Yale University Press; D.F.Glut (2002) The Frankenstein Archive: Essays on the Monster, the Myth, the Movies, and More, McFarland and Co; N. Michaud, ed (2013) Frankenstein: The Shocking Truth, Open Court; S. Denson (2014) Post-naturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface, Transcript-Verlag; and D. Horton (2014) Frankenstein: Cultographies, Wallflower Press.

3. As documented by: N. Bertram (1973) Daughter of Earth and Water: A Biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Morrow; D. Hay (2011) Young Romantics: The Shelleys, Byron, and Other Tangled Lives, Giroux; M. Seymour (2002) Mary Shelley, Grove Press; B. Johnson (2014) A Life with Mary Shelley, Stanford University Press; and C. Gordon (2016) Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wolstonecraft and Mary Shelley, Random.

4. This poem was written in the winter of 1818/1819 and is reprinted in P.B. Shelley (2003) The Complete Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Project Gutenburg Books.

5. As the following publications point out: J. Lancaster (2009) In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Cultural History of Naples, Taurus Parke; and T. Astarita (2013) The Companion to Early Modern Naples, Brill.

6. As reported by: D.R. Liddick (2011) Crimes Against Nature: Illegal Industries and the Global Environment, Praeger; R. Walters (2013) Eco Mafia and Environmental Crime, in K Carrington et al, eds, Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, Palgrave, pp281-294; C. Livesay (2015) Europe’s Biggest Illegal Dump — ‘Italy’s Chernobyl’ — Uncovered in Mafia Heartland, Vice News, June 20th issue; W. Mayr (2014) Italy’s Growing Toxic Waste Scandal, Spiegal Online, Jan 16th issue; and J. Yardley (2014) A Mafia Legacy Taints the Earth in Southern Italy, NY Times online, Jan 30th issue.

7. For explorations of Vesuvius’ history and geology, see: A. Scarth (2009) Vesuvius: A Biography, Princeton University Press; and C. Guerra (2015) If You Don’t Have a Good Laboratory, Find a Good Volcano: Mount Vesuvius as a Natural Chemical Laboratory in Eighteenth-Century Italy, AMBIX, Vol. 62 No. 3, August 2015, 245–265.

8. Incidentally, Mary Shelley writes of Viktor Frankenstein at this time as being a medical student/medical experimentalist. He wasn’t ‘awarded’ his doctorate and given the title ‘Dr. Frankenstein’ until the film versions of the Frankenstein story came to prominence in the 20th century. However, for our purposes, the title ‘Doctor’ is useful in conveying the respect Frankenstein was given by his peers in Ingolstadt whilst helping us to de-couple the name of the creature and the name of its creator. As well as this, we should note that in Shelley’s Frankenstein, the creator never gave his creature a proper name.

9. See: Audi (2013) Four Rings: The Audi Story, Delius Klasing Verlag.

10. As reported by: S.R.H. Barrett et al. (2015) Impact of the Volkswagen emissions control defeat device on US public health. Environmental Research Letters Volume 10, Issue 11; W. Boston et al (2015) Audi Engines Implicated in Volkswagen Emissions Scandal, The Wall Street Journal, November 27th, 2015; S, Tomlinsin (2015) Audi Says 2.1 Million Cars are Fitted With Cheat Devices, Mail Online: September 25th issue; and H. Tuttle (2015) Volkswagen Rocked by Emissions Fraud Scandal, Risk Management, Vol 62, issue 10, pp4-7.

11. See for example: http://www.france24.com/en/20170303-volkswagens-dieselgate-scandal-unfolded-after-2015-reveal-emissions-cheating.

12. See: Audi (2013) Four Rings: The Audi Story, Delius Klasing Verlag.

13. M. Shelley (1818) Frankenstein, Lackington, Chapt. 10.

14. See for example: M. Tennberg, ed, (2012) Governing the Uncertain: Adaptation and Climate in Russia and Finland, Springer; and R.W. Orttung (2016) Sustaining Russia’s Arctic Cities, Berghahn

15. E. Larsen and H. Lindenberger (2016) On Thin Ice: An Epic Final Quest into the Melting Arctic, Falcon Guides.

16. B.S. Levy and J.A. Patz (2015) Climate Change and Public Health, Oxford University Press; A. Luhn (2016) Anthrax Outbreak Triggered by Global Warming Kills Boy in Arctic Circle, The Guardian Online, Aug 1st issue; and T. Nilson (2016) Yamal Anthrax Could Be Just the Beginning, The Independent Barants Observer, Aug 7th issue.

17. As predicted by such scientists as: CCRC (2002) Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises. Committee on Abrupt Climate Change, Ocean Studies Board, Polar Research Board, Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, Division on Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council. National Academy Press: Washington, D.C.; D. Cox (2005) Climate Crash: Abrupt Climate Change and What it Means for Our Future, Joseph Henry Press; and R. Alley (2014) The Two-Mile Time Machine: Ice Cores, Abrupt Climate Change, and Our Future, Princeton University Press.

Alan Marshall has a PhD from Wollongong University (Australia) and has previously worked on international projects in environmental design and environmental ethics. His books on these subjects include: Ecotopia 2121 (2016), Dangerous Dawn: The New Nuclear Age (2006), Wild Design: The Ecomimicry Project (2009), and The Unity of Nature (2002). Currently, he teaches Environmental Social Science to masters degree students at Mahidol University, Thailand. (alan.mar@mahidol.ac.th)

Nanthawan Kaenkaew has a BSc in Computer Science from Suan Sunundha Rajabhat University (Thailand) and is a specialist in the visualization of science reports/projects.

Volume 1, no. 3 Autumn 2017