The New Economics Foundation on tackling the housing crisis

with Hanna Wheatley

Hanna Wheatley is a Senior Researcher in NEF (New Economics Foundation), mainly working on housing and land, currently leading NEF’s work on the public land sale in the UK. A London-based think-tank and consultancy, NEF aims to transform the economy so it works for people and the planet. We spoke to her about the role of land in the context of the housing crisis and alternative ways through which people can shape development and access housing.

1. Housing in cities across the world is becoming increasingly unaffordable. What have been the manifestations of such a trend in London and the UK?

The UK has a deep and worsening housing crisis. House prices in the UK have more than trebled in the last 20 years and wages have fundamentally failed to keep up. This is especially true in London, where the house-price-to-earnings ratio, wages as a proportion of the cost of a home, has doubled since 2000. The result of these trends is stark. There are growing numbers of families and older people trapped in the insecure private rented sector, homelessness has doubled since 2010, there is a vast housing benefit bill, and estimates of social housing need are now as high as 3.1 million homes.

Prices in the private rented sector are also increasingly outstripping wages in some places. Since 2010, average private rents in London have risen more than three times as fast as average earnings, and in 2015/16 around a quarter of privately renting households in the capital spent over half of their income on rent. Affordability is far worse in London than most of the rest of the country, with the average private rent for a one-bedroom home in the capital now more than the average for a three-bedroom home in every other English region. Elsewhere, while affordability isn’t such a problem, quality and standards are, and the sector as a whole is one of the least regulated in Europe, meaning the balance of power almost always favours landlords.

And this was all true before the Covid pandemic took hold. With an expected recession, the lifting of the evictions ban, and the potential of a second wave, many organisations are warning that homelessness could rise as a result. When housing is so unaffordable and insecure, many people are not able to have a buffer against shocks like this, and are at risk of losing their homes.

2. Has it always been this way? What is driving housing unaffordability?

Fifty years ago, the country had a fairly stable housing system where the need for secure, affordable housing of the middle class was largely met through homeownership, and that of the working class through widely available social housing. But a policy environment characterised by a reliance on the private market to deliver homes since the 1980s, the increasing availability of mortgage credit, and the loss of millions of social homes over recent decades, has destroyed this system.

At NEF, we often talk about the role that land plays in the economy and in the housing crisis. Various studies have modelled how much of the cost of a home is made up by the cost of the land and have found that it can be up to 70% depending on geographic location. Another study of 14 advanced economies found that 81% of house price increases from 1950-2012 could be attributed to rising land prices.

The last few decades in the UK have seen a move away from the mixed model of development, and an increased reliance on private developers for the majority of housing output, whose business model is speculative. This combined with the rules that fix land prices means that land prices have skyrocketed. Developers offer high prices for land, on the assumption that they can build expensive, private market homes and drip feed these homes onto the market to keep prices high. Speculation in property markets has so far helped to ensure that there is almost always high demand, because houses are no longer only seen as homes in the UK, they are also seen as assets.

This has all been enabled by the deregulation of finance that has occurred since the 1980s, changing the role of the bank and its relationship to the housing market. The wide expansion of mortgage credit to boost home ownership has replaced banks’ traditional role of recycling savings into productive investment with a system where banks create credit against the collateral of land, resulting in rising land values. Now, the housing crisis is most severe in places with high land prices, which have higher house prices, higher rents in the private rented sector, and also reduced social house building because high land prices make building it unaffordable for developers and housing associations.

3. We often hear that “we’re not building enough housing fast enough”. Is this the case and is this a reason why housing is less and less affordable?

It’s a common assumption that just building more homes will make houses cheaper. Politicians and the media talk about housing as a supply-side problem, suggesting that we could solve the housing crisis if we just had more houses, or the more problematic flip side, if we had fewer people. The logic here is that if you have more houses, prices will go down because there will be less competition – simple supply and demand. But treating the housing crisis as an issue of supply only, as most mainstream and free-market economists tend to do, ignores the changing role of housing and land in the UK.

Because of the expectation of further price rises, a house is no longer just a place to live, and houses have started to be treated more as assets than as homes. This has led to a huge rise in unhealthy speculative demand, where there is almost always high demand from non-resident investors or Buy to Let landlords (again, encouraged by the policy environment). Some of these investors are the super wealthy, and people like to talk about foreign investors using London property as a money laundering service, creating situations where whole streets of luxury properties are sitting empty in the capital. But it’s not only the super wealthy who increase this demand: the expansion of mortgage credit at a time characterised by stagnating wages, the rolling back of the welfare state and a reduction in pension provision mean that for many ordinary people, getting a mortgage to buy property is a good long-term investment. This in turn creates a warped private rented sector, because government incentives like Buy to Let tax breaks mean that many people become landlords not because they want to offer a service to tenants, but because they want to have a comfortable pension, leading to high rents and poor quality in the private rented sector.

1. Just building more homes won’t solve the housing crisis alone. Souce: Pixabay.

4. There’s also a view that is recurring, most recently in the current government’s agenda, that “Planning is limiting our capacity to grow and produce the houses we all need”. What is your view?

The government’s latest intervention into the housing market has been to propose a massive overhaul of the planning system, cutting the ‘red tape’ that developers argue is preventing them from building homes quickly enough. In many ways, our planning system is complex, but it’s the main democratic function mediating between competing interests over a finite resource, and importantly, it’s not driving the housing crisis in the way developers and politicians make out.

Around 90% of planning applications are currently approved but there are up to 1 million unbuilt permissions. Over a million homes were given planning permission in the last 10 years but were never built. Because of the speculative development model and rising land prices we now have in the UK, developers are incentivised to ‘land bank’. They either hold land with planning permission, or, hold land without planning permission in areas they expect will see a rise in land prices over time. Even once homes are built, developers, who are duty-bound to maximise profit for their shareholders, will drip feed them onto the market to keep prices high.

In fact, when we hear developers bemoaning planning regulation and red tape, they are often exploiting narratives about the housing crisis to build public support for policy changes that would allow them to further profit by reducing quality standards and affordable housing contributions. Planning rules are the basic standards that help deliver social and affordable homes in decent neighbourhoods that people want to live in, and the planning system, while imperfect, allows local people to have a say. Stripping it away, as the government is currently hoping to do, isn’t the answer.

5. A lot of NEF’s recent work has focused on the sale of public land. What is the role of public land in housing provision and affordability?

National and local-level governments have historically owned a large amount of land, but over time, more and more of it has been privatised. Based on a dubious discourse around the existence of ‘surplus’ public land and the supposed ‘efficiency’ of private ownership, Brett Christophers estimates that 2 million hectares of public land, worth £400 billion, has been sold to the private sector in recent decades, representing 10% of the British land mass.

At NEF, we’ve focussed on the most recent wave of the central government land sale. Since 2011, the coalition and Conservative-led governments have pushed policies encouraging the disposal of public land with the stated objective of stimulating housing supply and ‘fixing our broken housing system’. Across two policies running from 2011-15 and 2015-2020, enough central government land for 260,000 homes was set to be sold. However, because of the speculative model of housing and land outlined above, the results of this public land sale have been pitiful.

In most places, solving the housing crisis means providing truly affordable housing, and so building social housing should be a top priority, but there have been no efforts to treat public land differently to any other kind of land in the UK, meaning it has also been beholden to the speculative development model. Our research shows that only 2.6% of homes planned on public land sold since 2010 are for social rent. Only 15% are for any kind of affordable housing. The planning documents make for pretty depressing reading, when mental health hospitals are shut down and turned into luxury flats and the developer wriggles out of their affordable housing commitments on the grounds that they won’t be able to make a profit given the price of the land.

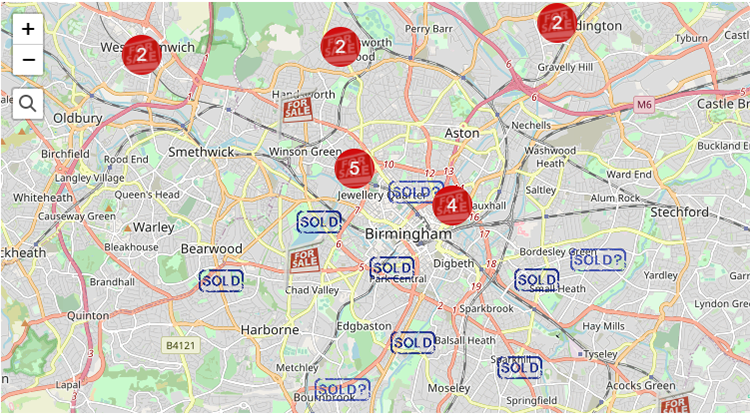

2. The government is selling public land to developers all over the country. Source: New Economics .

6. What are we effectively losing when we lose public land?

The government faces multiple barriers when trying to squeeze affordable housing out of big developers on land it has no control over. But by selling public land at maximum market prices to the same developers, it is missing a once in a lifetime chance to use that land for public good. If public land is in a suitable place with a need for social housing, it should be used to provide that, with central government and local authorities playing a much bigger role in developing the homes people actually need.

We should see the sale of public land as part of a continuing trend of privatisation in the UK. Once the services and assets are sold, from Thatcher’s privatisation of state-owned industries to the introduction of Right to Buy for council houses, to the current ‘rationalisation’ of the central government estate, it becomes increasingly difficult and expensive to get them back. We lose clear democratic control over things that once were managed for the public good and now are managed for private profit.

7. Can we really “change the rules” for land development in London and the UK? How?

Many of the problems with the British housing system can be traced to a reliance on private developers operating on a speculative model of development. The results are widening inequality between those who own land and those who don’t, and huge windfall gains going to land promoters and private developers.

This model has not provided the kind of homes we need to solve the housing crisis, and in current conditions, it never could. That’s because profit motive, and the price of land, essentially dictate what is built on land, instead of community need. In order to change this, we’d need to see a much more diverse system instead of the monopoly of big developers, a fairer system of land pricing, and we’d need to see more land acquisition and building done by democratically elected bodies with direct involvement from the communities affected. It’s telling that Homes England, the non-departmental body responsible for selling a lot of public land, currently has no strategy for community engagement about public land sites or even a public target for affordable housing on their sites.

At NEF, we’ve called for a new public body, which would be responsible for assembling and developing land in the public interest, primarily for social housing, by bringing together public and private land, acquired under revised land acquisition powers. Many other countries, like Germany and Denmark, have created regulations which allow the state to purchase land at the existing use value of the land rather than having to compensate the owner for ‘future hope value’ (i.e. a field is priced as a field, not as its potential price if it had a block of luxury flats built on it). There have been calls from across the political spectrum to reform the Land Compensation Act to allow the public sector to purchase private land at closer to existing use values, backed by compulsory purchase, and recent analysis has found that this could reduce the cost of a high-density apartment block in London by 33%.

Public land on the other hand, which the government already owns, offers a quicker fix because they don’t need to acquire it. For public land, the Treasury rules need to be reformed and clarified so that it is clear that public bodies can manage their surplus land for public good, rather than just for the highest cash receipts. The land system as a whole is in urgent need of reform, and delivering an increased programme of social housebuilding will require public bodies to be able to both build on land they already own, and purchase private land at fairer values.

8. How do people and communities on the ground trace alternative ways to land development and housing accessibility?

Numerous community groups have been set up to counter the development plans on former-public land across the UK. From StART Haringey, who are working with the Greater London Authority to influence a community-led development on the former St Ann’s Hospital site in London, to Fossetts for the People, who are currently intervening in the planning process of Fossetts Farm, an ex-NHS site in Southend, to campaign for more affordable and key worker housing. These groups face significant barriers trying to build local support around the often-opaque planning processes, and are up against big developers and Homes England who have a lot more resources and institutional power. But both of these groups have been successful in gaining local support and bring the local or regional authority onside through building public pressure.

Beyond intervening in the public land sale, there are also numerous groups doing things differently and pioneering alternative models of affordable home ownership. In the UK, there is a long history of cooperative and self-organised housing provision, including community land trusts and community led housing, and there are a number of active projects across the country today, from Granby Four Streets in Liverpool, to Lilac in Leeds.

But while they have undoubtedly made a difference in their local area and to the people involved, these pockets of resistance face a number of barriers and struggle to offer the scale of affordable housing we need, or tackle the root causes of the housing crisis.

3. Sisters Uncut activists on the roof of old Holloway Prison visitor’s centre, 27/05/2017. Source: North London Sisters Uncut.

9. What are the obstacles to overcome if we were to mainstream such approaches?

Access to land is one of the biggest barriers to trying to do things differently. The price of land stymies attempts to build affordable housing because of the speculative development model described above. This also creates barriers preventing communities from taking matters into their own hands and developing themselves. Community groups invariably lack the funds to purchase land in the places most in need of affordable housing.

However, the major barrier to these approaches becoming mainstream is scale. In Scotland, Community Right to Buy, a policy announced in 2003, allows communities to apply to register an interest in land and the opportunity to buy that land when it comes up for sale. The government offers funding and support for groups aiming to do this. And yet, even while they are miles ahead of the national UK government, the take up is still not widespread and Scotland faces its own housing affordability crisis.

In reality, the only times we have ever built enough affordable homes to meet demand is when the public sector has stepped in to build. 2019 marked 100 years since the Addison Act was passed, which introduced the notion of councils building social housing on a large scale. 5.5 million social homes were built over the next century, but the trend has slowed massively since the 1980s. In 2018 – 19, only 6,287 social rented homes were built.

10. How does NEF work with communities fighting public land sale?

Alongside our national campaign against the public land sale policy, our organisers have worked on the ground with communities fighting the sale in their local areas for the last few years. One example is the work we’ve done with residents and NHS staff in Southend to build Fossetts for the People, a campaign fighting to ensure that former NHS land is used to provide hundreds of new council homes.

A site at Fossetts Farm in Southend was formerly owned by the NHS, who planned to build a new medical centre. When these plans were abandoned, the site was sold in August 2018 to Homes England. The developer paid only £7.8 million for the site, but FFTP claims that with planning permission for residential homes the true value of the land could exceed £40 million.

Southend is suffering from a lack of good quality, affordable social housing. FFTP was set up to demand that the council use the land for social housing, which would provide much needed homes for Southend residents, and would bring revenue to the cash-strapped council. The group say that 400 new homes could be built on the 14-acre site through a publicly owned Local Housing Company.

We’ve worked with them for the last two years, with organisers and researchers attending their committee meetings and offering our support and resources. Despite significant local opposition, including some from council cabinet members, a planning application was submitted to Southend Borough Council shortly before lockdown began, for a development that would only have a maximum of 20% affordable housing. No assurance was given over the type of affordable housing this would be. In response, the campaign pulled off the amazing feat of mobilising at the beginning of lockdown, getting over 120 objections lodged from individuals and groups in Southend.

4. Fossets for the People and the New Economics Foundation at the Labour Party Conference 2019. Source: Gaz De Vere

11. If there was one thing you could change right now in the way land is being owned, managed, developed, what would it be?

The housing crisis we find ourselves in is the result of decades of poorly designed policy, so there is no one silver bullet that would untangle the mess immediately. But a key change would be increasing public and democratic ownership of land. Public and democratic ownership alone isn’t enough, and communities and public bodies need to be enabled to use their land in socially useful ways, but it is a vital first step.

Holding land under permanent public ownership can ensure that public good is a guiding principle in any development of the land, as opposed to profit. It would also ensure a level of democratic control over the land, so people would have a say over what happens to where they live. Public ownership in other countries like Singapore and Hong Kong also generates a long-term income for the state and public services through long term and commercial leasing of public land to businesses.

A key mechanism for doing this in the UK, compulsory purchase, would need to be reformed to make this happen. Currently, like many other countries, the UK state has the power to acquire rights over land without the owner’s consent, in return for compensation, under compulsory purchase powers. But under the current legal framework here, public authorities cannot purchase land at close to “existing use value”. The Land Compensation Act 1961 enshrines the principle that landowners are entitled to “hope value” on any land compulsorily purchased. This means that the price of land can be incredibly high because it is based on what value the land could have in the future, e.g. if it acquired residential planning permission. The gap in some areas between the agricultural value and the residential value, for example, is stark – with agricultural land increasing in value with planning permission often by more than 300 times. Such a huge uplift in value means the state is unable to use the compulsory purchase powers we already have here, and even if they could, it would compromise the viability of including social and affordable housing.

If the government were able to assemble public land sites they already own, and adjacent and other private land at a fairer price, they would be able to reclaim their role in directly delivering the social housing we need to have a housing system fit for purpose. The government should once again see the provision of safe, secure, affordable housing as their responsibility, and work to build the next generation of social housing.

Notes

1. The housing benefit bill is the total amount of benefit paid by the government to those on low incomes to help to cover the costs of rent. Because of the reduction of social housing and the expansion of the private rented sector over time, the total cost is now very high, around £22 billion a year, and is one of the government’s biggest yearly expenditures.

2. The Right to Buy scheme is a UK policy that was introduced in 1980, allowing tenants the legal right to buy their council house at a large discount. It is credited with the privatisation of almost two million council homes. In 2018 there were over one million households on the waiting list for council housing in England alone.

3. “Buy to let” landlords buy property specifically to rent it out. Before the 1980s, the private rented sector was smaller and run by professional landlords. Since then, banks and the government have made it much easier (and more attractive) for ordinary people to take out specific buy to let mortgages, creating increased speculative demand in the housing market.

Volume 3, no. 3 Autumn 2020